…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

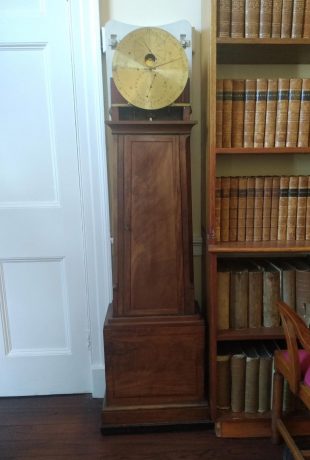

Astronomical Regulator: Hardy

Made by William Hardy and known as 'Hardy' since the mid 1830s, this particular regulator was delivered to the Observatory in 1811 and remained in continuous use as a Transit Clock until 1954. It is one of the most important clocks that the Observatory ever owned. During the 143 years that it was in active service, the Observatory was headed by five different Astronomers Royal: John Pond (1811–1835), George Airy (1835–1881), William Christie (1881–1910), Frank Dyson (1910–1933) and Harold Spencer Jones (1933–1955). During its lifetime, it underwent numerous and significant alterations.

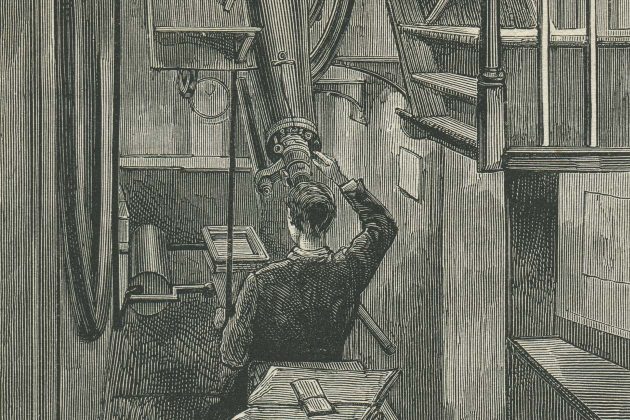

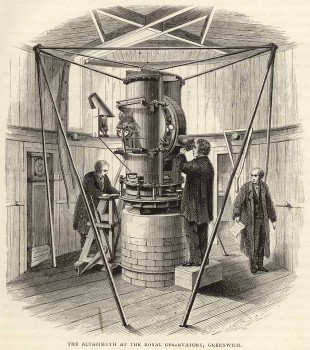

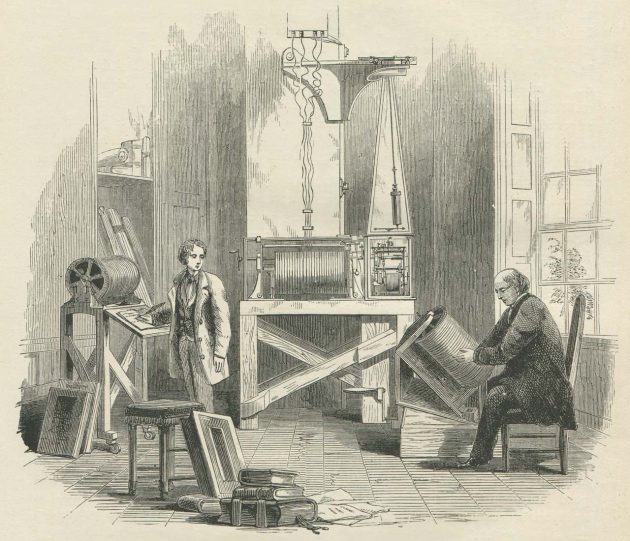

Hardy in use with the Airy Transit Circle. The observer is in a pit below the level of the floor. The dial can be seen towards the top left. From the 8 August 1885 edition of The Graphic (detail)

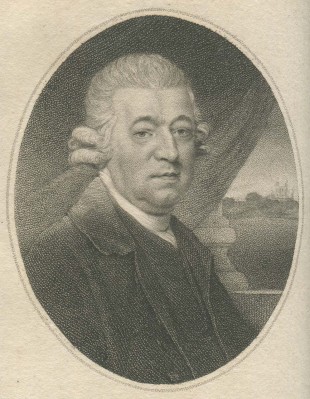

Although the clock was ordered by the fifth Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, he does not appear to have lived long enough to see it brought into use. When it was ordered, the intention was to use it as a Transit Clock with a Mural Circle that was then under construction.

As originally conceived, the plan was for the Mural Circle to replace both the existing 8-foot Transit Telescope and the Mural Quadrants. In practice, it proved insufficiently stable to make reliable transit observations, so a new 10-foot Transit Instrument was ordered from Troughton in 1813. It was brought into use in 1816 and used initially with Graham 3, the same Transit Clock that had been used with its predecessor. In 1821, Graham 3 was dismounted and replaced by a series of transit clocks in quick succession (some or all of which appear to have been supplied on a trial basis), starting with a clock by Molyneux and Cope. None appear to have been satisfactory. By late 1823, Hardy needed to be moved to make way for a second Mural Circle in the Circle Room and it was at this point, that it was transferred from the Circle Room to the Transit Room for use with the 10-foot Transit Instrument.

In 1851, the Airy Transit Circle, replaced both the 10-foot Transit Telescope and the Mural Circles. Hardy remained in use as the Transit Clock and continued to be used with the Transit Circle until the last observation was taken in 1954.

Until 1871, when the regulator Dent 1906 was brought into use, the Transit Clock was the Observatory's de facto sidereal standard.

Today, Hardy can be seen on the south side of the Airy Transit Circle in the same position that it has occupied since December 1850. It is cared for by the National Maritime Museum (Object ID: ZAA0591). A replica pier (similar to that used with an earlier transit clock) was erected beside the Troughton Transit Instrument by the Museum in the mid-1960s, and marks the position Hardy occupied from 1823 until 1850.

Management and oversight of the Observatory in the early 1800s

Nevil Maskelyne, the fifth Astronomer Royal. Engraved from a pastel drawing by John Russell and published by J. Asperne, 1 March 1804

Sir Joseph Banks. Engraving by W. Holl from the 1815 oil painting by Thomas Phillips. � The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), details below

To understand the early history of the clock, it is helpful to understand a little more about the relationship between Maskelyne and the President of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks, as well as how things were handed over to Pond when he became Astronomer Royal following the death of Maskelyne in early 1811. Banks and Maskelyne were both Commissioners of the Board of Longitude and Maskelyne was answerable to the Observatory's Board of Visitors of which Banks, as President of the Royal Society, was Chairman (and had been since 1778). Maskelyne also held high office at the Royal Society, having been a longstanding member of its Council. Their working relationship on the Board of Longitude came under severe strain in 1784 and an abrupt end in 1806 when Banks stopped attending meetings following a disagreement with his fellow Commissioners, and in particular Maskelyne, about an award made to Thomas Earnshaw. Although Banks had stopped attending meetings of the Board of Longitude, Maskelyne who by then was in his mid 70s, continued to attend meetings of Council of the Royal Society.

It was during Bank's absence at the Board of Longitude that the seeds were sown that led to the Nautical Almanac being brought into disrepute in the 1810s. This was due in large part to a lack of succession planning. The comparer Malachy Hitchins (1741–1809), the Board's Secretary, George Gilpin (c.1755?–1810), and Maskelyne (1732–1811), all died in quick succession while still in office. During this period, the Board normally met just three times a year. The meeting on 7 March 1811 was the first to be held following the death of Maskelyne and the first that Banks had attended since March 1806. None of the members of the Board appear to have had a clue about what was involved in managing the production of the Almanac as it was resolved:

‘That the Astronomer Royal [Pond] be requested to conduct the business of the Nautical Almanac by superintending & paying the Computers and Comparer in the manner that has been heretofore done & that the Secretary be requested to allow him access to the Minutes of the Board in order that he may collect from them the mode in which that business has been hitherto carried on.’(RGO14/7/145)

What is striking is that Pond wasn’t handed a dossier by the Secretary setting out how the Almanac had been managed and what the present state of play was. He was required instead to extract this information from the Board’s minutes. This would have been an all but impossible task since the minutes, of which 800 pages had been accumulated since the Almanac was conceived in 1765, did not contain the information in the detail that Pond would have needed. So what of the handover to Pond of the Observatory business?

We know that there was no ongoing correspondence included amongst the ‘Printed Books Manuscripts and Pictures left and presented by Mrs Maskelyne at Flamstead House for the Use of the Royal Observatory’ that were formally handed to Pond by Maskelyne's widow when he took up residence in April (RS/MS372/168 & NMM REG09-000037).

But we also know that Pond dined with Maskelyne at the Observatory on at least seven occasions between 1806 and 1809. He may also have dined after 1809, but there are no surviving records for this period. Pond was elected a fellow of the Royal Society on 26 February 1807. As well as becoming a member of the committee that looked into the acquisition of the Mural Circle, Pond was one of the fellows invited to attend the Observatory as a Visitor on 10 July 1807 (RGO6/22/56). He was also invited to all the later Visitations. However, the only ones he attended prior to his appointment as Astronomer Royal were those in 1807 and 1810 (RGO6/22). In late 1810, he was also brought onto the Council of the Royal Society.

Pond was clearly familiar with some aspects of the way in which the Observatory was run during Maskelyne's time. But what if anything did he know either about the likelihood of succeeding Maskelyne or about the clock? Although Maskelyne made his last observation on 1 Sep 1810, a little over 3 months before he died, there is no record of any succession planning having taken place. The catalogue of Maskelyne's papers (RGO4) makes no reference to either Hardy or the purchase of a new Transit Clock, suggesting that Pond may have had little if any knowledge of what had been agreed between Maskelyne and Hardy. The fact that the catalogue also makes no reference to the Mural Circle is also interesting and leads us to ask: was the paperwork retained by his widow, was it handed to Pond, but subsequently destroyed or is there some other explanation for its absence?

The documentation surrounding the early history of the clock is very sketchy. Much of what survives is contained in the Royal Society file RS/MS/372 and the minutes of the meetings of its Council. Extracts from the minutes from 1710–1830 deemed relevant to the Royal Observatory were transcribed for George Airy and can be found in RGO6/21&22. What, if anything, was omitted is not known and a comparison with the originals would be needed to find out – a task that no researcher has yet undertaken in any sort of a systematic manner. It is known however that the resolution relating to the clock that appears in the minutes of the committee that met on 22 January 1807 and mentioned in the section below (RS/MS600/59) does not appear with the rest of the minutes of the committee that were transcribed into RGO6/22 as part of the minutes of the Council meeting held on 19 March 1807 (RGO6/22/53). It is not yet known if this was because of an error made when the committee minutes were transcribed into the Council minutes or when the Council minutes were transcribed for Airy.

The need to re-equip the Observatory – the chronology of events leading up to a new clock being ordered from Hardy

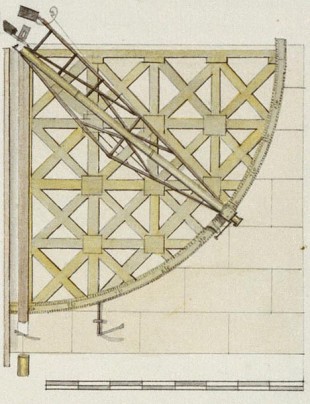

Bradley's Mural Quadrant. Detail from a drawing by John Charnock c.1785. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) licence courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London (see below)

Nothing much happened until 22 January 1807, when a specially convened committee of the Society resolved that the Royal Observatory should be provided with a vertical circle together with a clock to go with it and a new room to house them in (RS/MS600/59). Pond was subsequently co-opted onto the committee, and later that year, a large Mural Circle was ordered for the Observatory from the instrument maker Edward Troughton with the intention that it would supersede both the Mural Quadrants and the 8-foot Transit Telescope.

Meanwhile, back on 8 January 1807, the chronometer maker William Hardy had written to to George Gilpin, the Secretary of the Board of Longitude explaining that he had invented a new form of spring pallet escapement and asking if it could be put on trial at the Royal Observatory (RGO14/23/239). Perhaps in part because the Observatory was looking to acquire a new clock, at its meeting on 5 March 1807, Maskelyne and the board assented. Hardy records that:

‘He [Maskelyne] accordingly called on me the day after the meeting of the Board, to see the escapement; and being pleased with it, desired me to send the clock to the Observatory for trial, as soon as I possibly could.’

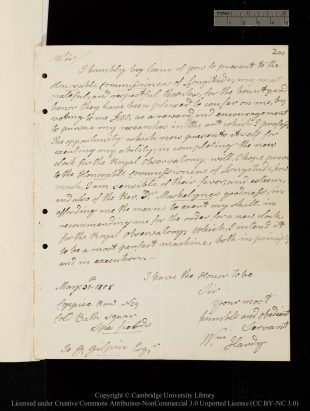

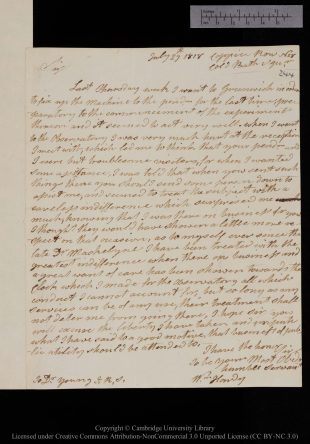

Hardy's letter to the Board of Longitude containing the first mention of a clock being ordered for the Royal Observatory. It was written on 31 May 1808. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

Thomas Earnshaw (1749-1829), attributed to Sir Martin Archer Shee, 1798. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence courtesy of The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum (see below)

In the mean time, at the end of May, a three month trial of the clock had already begun.The details of the trial are gone into in more detail below, but at this point it is only necessary to know that the results were not tabled at the next meeting of the Board, but at the one after that on 3 March 1808, where it was resolved: 'That the sum of £50 be given to Mr William Hardy as a Reward for the performance of his Clock, and to encourage him to proceed in the farther improvement of Clocks.’ (RGO14/7/115).

Maskelyne subsequently ordered a clock from Hardy for use with the new Mural Circle. Exactly when the order was made is unclear as the first we hear about it is from a letter that Hardy wrote to the Board on 31 May 1808 thanking them for their award in which he wrote:

‘I am sensible of their [the Board’s] esteem and also of the Rev. Dr. Maskelynes goodness, in affording me the means to extend my skill, in recommending me for the order for a new clock for the Royal Observatory, which, I intend it to be a most perfect machine, both in principle,and in execution.’ (RGO14/1/200)

In the meantime, in February 1808, Thomas Earnshaw was writing the introduction to his pamphlet: Longitude: an appeal to the public: stating Mr Thomas Earnshaw's claim to the original invention of the improvements in his timekeepers, ...which was published later that year.

Long before Hardy had launched himself onto the clock-making scene, Maskelyne had asked Earnshaw to make a clock for the observatory in Armagh. The clock he produced performed exceedingly well when put on trial at the Royal Observatory in 1792 before being shipped to Armagh in 1794. Like the clock that Hardy was to make, it had both jewelled pallets & pivot holes. Unlike Hardy's clock it also had a sealed case to keep out dust and draughts and, according to Earshaw, had been running for the past 14 years without being cleaned. On page 48 of his Appeal, Earshaw wrote the following:

'After I had pointed out to Dr. Maskelyne the absurd manner in which the famous Mr. Arnold had jewelled the transit clock [Graham 3] at Greenwich, he wanted me to re-jewel it, and do any thing else I thought necessary; I refused, saying, that let me do what I might, it was still Graham's clock, and his name was on it, and if the Royal Society, after the proofs I had given of my superiority, did not choose to order as good a clock of me, as I could make, they might keep their old one as it was, as a standing monument of disgrace to Mr. Arnold and others, who had botched it up in the manner it now is.'

Given Maskelyne's championing of Earnshaw and the proven performance of not only the clock that he made for Armargh, but also others that he made subsequently; it has to be asked, why was the commission for the new clock at Greenwich given to Hardy who had no proven record beyond a short trial of his new escapement? One can only speculate on the reason. Perhaps Maskelyne did suggested him and Banks vetoed the idea or maybe Maskelyne chose not to suggest him for fear of opening up old wounds.

Images of the clock and the documentation of its history

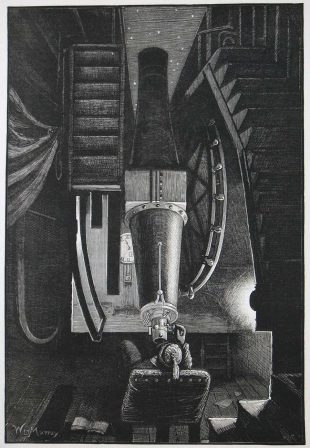

The Airy Transit Circle with Hardy in the background. The illustrator, William Bazett Murray, has simplified the dial beyond recognition. From the 11 December 1880 edition of The Illustrated London News

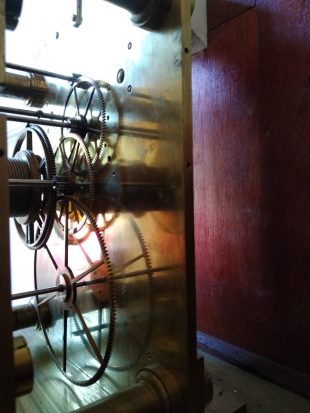

The earliest photos seem to be those taken for conservation purposes in the mid and late 1960s. Showing details of the movement, they have never been published. Nor have any others that show the movement. Even today, the clock is rarely if ever photographed by Museum visitors.

The only known images prior to the 1960s are two woodcuts of the Airy Transit Circle in which the clock appears in the background. Lacking in detail, they were published in the 11 December 1880 edition of The Illustrated London News (right) and the 8 August 1885 edition of The Graphic (from which a detail is reproduced above).

No correspondence has been found between Hardy and Maskelyne or between Hardy and Pond apart from a single letter sent by Maskelyne that appears to have ended up in the hands of the bookseller John Nourse and is now in the collections of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The clock has a complex history which is made all the more difficult to unravel not only due to the lack of images, but also because the records are often rudimentary and not always complete. Snippets of information are spread thinly across a very wide range of sources including the Royal Society archives, the Observatory archives and the published volumes of observations. Tracking them down is rather like looking for possible needles in a large but unknown number of haystacks.

Five key features of the Greenwich Clock as originally supplied

- Hardy's escapement

- Accurately cut epi-cycloid shaped teeth on the wheels and pinions

- Jewelled bearings and pallets

- A mercury compensated pendulum

- An integrated stone pier which formed part or most of the case

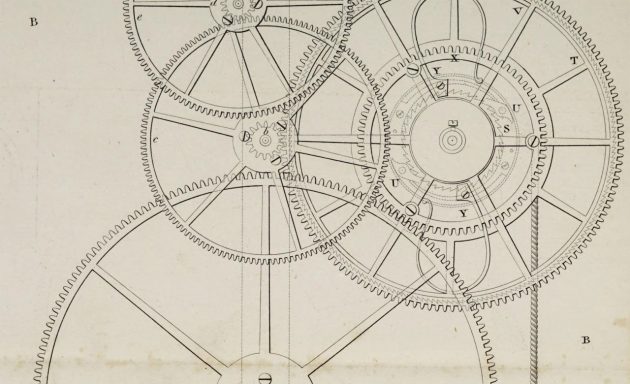

The epi-cycloid shaped teeth on the wheels and pinions of Hardy's regulators. Detail from plate 34 accompanying Hardy's description of his escapement. Reproduced from Transactions of the Society Instituted at London for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. Volume 38, courtesy of the Wellcome Library & Internet Archive

Servicing and altering the clock: the Hardy and Dent correspondence

Although Hardy came to the Observatory to service or alter the clock, as mentioned above, none of the correspondence appears to have been preserved. Hardy continued to have responsibility for the clock until 1830 when he failed to respond having been asked twice to attend. Not having received a reply Pond turned to Edward Dent instead (more on this below). As things turned out, Hardy never worked on the clock again. Although he did not die until 1832, it was Dent rather than Hardy who attended when the clock next needing cleaning at the end of 1831. From that point on, Dent was always the clockmaker called on by Pond and his successor Airy to work on the clock.

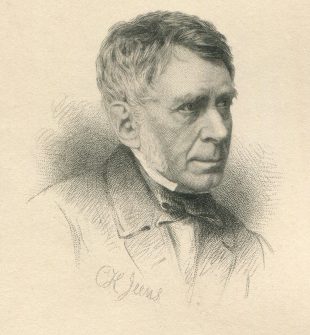

George Airy engraved by C H Jeens from a photograph probably taken by Alfred Brothers in Manchester in September 1861

The Dent company names include:

1826–30 E.J. Dent

1830–40 Arnold & Dent

1840–53 Edward J. Dent

1853–61 Frederick Dent

1861–64 Dent & Co

1864–97 E. Dent & Co

1897–today E. Dent & Co. Ltd

Altogether, there are around 800 sheets of correspondence between the Observatory and the Dent companies that relate to the Observatory clocks during Airy's period in office (1835-1881). All except those from the year 1878 (which are missing) are preserved in the Correspondence with tradesmen files (RGO715-758). They exclude the correspondence relating to chronometer trials, which Airy filed elsewhere. Although other makers started to be used as well after Airy retired, the Dent companies continued to do work for the Observatory until at least 1920.

One of the difficulties with the Dent correspondence is that clocks are not always identified by name. Another is that the correspondence is just one part of an ongoing dialogue that continued in spoken form while Dent or his aides or staff from the successor companies were at the Observatory. Not being privy to those conversations makes some of the correspondence difficult to follow.

Research is still ongoing. All the Dent correspondence in RGO6 relating to years when work on the clock is mentioned in the volumes of Greenwich Observations or the Reports of the Astronomer Royal has been examined in detail as has the correspondence from certain other years. The remaining correspondence (1841–1848, 1852–3, 1857–63 and 1865–69 ) will be examined during the next few months.

Articles and chapters on Hardy's escapement and regulators

Greenwich Observatory, Vol 3. Derek Howse (1975), p.p.132–133

What’s Wrong With Hardy’s Escapement? Christopher Wood, Volume 9/8 (September 1976)

William Hardy’s Regulator. A.J. Turner, Volume 11/6 (Winter 1979)

William Hardy and His Spring Pallet Regulators. Charles Allix, Volume 18/6 (Summer 1990)

Design Analysis of a William Hardy Regulator Spring Detent. Leslie Paton, Vol. 19/2 (Winter 1990)

What’s Wrong With Hardy’s Escapement? A Re-Appraisal. Christopher Wood, Vol. 20/4 (Winter 1992)

Horological Journal

The performance of a 19th century regulator. John Redfern & Philip Woodward, Vol 135/9 (March 1993)

English Precision Pendulum Clocks. Derek Roberts (2003), pp. 83–94.

Maskelyne, Astronomer Royal. Rory McEvoy, Ed. Higgitt (2014), chapter 5

The bulk of the original work that has been published about Hardy's regulators has appeared in the various horological journals and sits behind a paywall. Some accounts draw on Howse, who made a number of incorrect statements. In his book, Robert's has drawn heavily on some of the Journal articles where there were already misunderstandings and created an even more misleading account strewn with errors. This is particularly unfortunate as the book is a first point of reference for auction houses.

1807: Hardy's escapement tested at the Observatory for the Board of Longitude

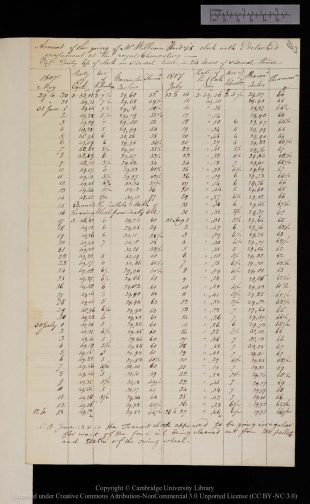

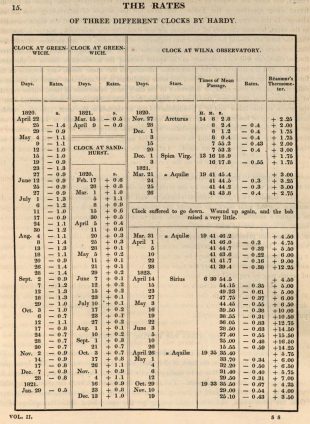

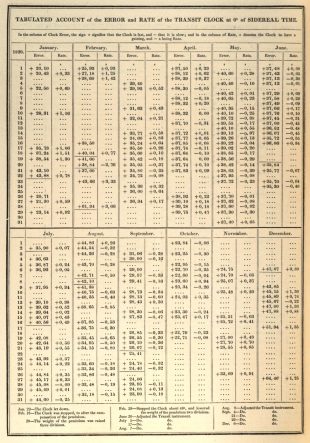

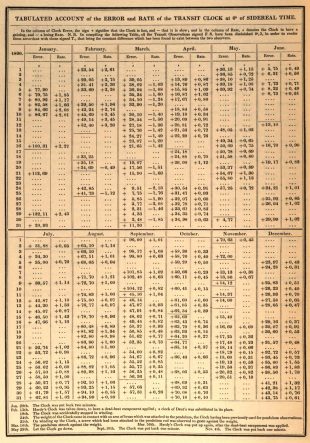

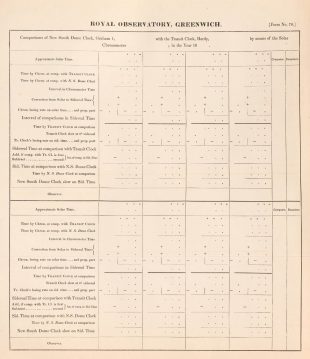

Trial results showing the rate of the clock. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

The results of the 1807 trial are reproduced alongside. Against the entry for 15 & 16 June, Maskelyne has written 'Cleaned the pallets & teeth of the swing Wheel from dirty oil'. At the bottom of the page however, Maskelyne has also written:

'N.B. June 13 & 14 the Transit clock [Graham 3] appeared to be going irregular for want of the foul oil being cleaned out from the pallets and teeth of the swing wheel.'

What Maskelyne did not record, was that Graham 3 was stopped on the following day to clean it. This information comes from the 15 June entry in the published observations where Maskelyne's Assistant Thomas Firminger recorded:

'At 6h24' stopped the Transit Clock, and cleaned away all the dirty oil from the swing wheel and pallets of the verge; then put a little of the best olive oil to them, and set the clock going again, exactly one minute faster than before. The clock was stopped 24 minutes. T.F.

Having stopped Graham 3, it would have had to be re-rated before the rate of Hardy's clock could be measured again. In light of this, it has to be asked, what exactly did Maskelyne mean by his entry for the Hardy's clock on 15 & 16 June? Was the Hardy clock stopped and cleaned or was the entry a somewhat ambiguous reference to Graham 3 that was partially clarified by the note at the bottom of the page? If Hardy was cleaned, it was probably only done as a precaution while the trial was paused while Graham 3 was being cleaned and re-rated. It also seems likely that Hardy would have been summoned to clean it. There is no evidence that he was sent for.

Very few Hardy escapements still exist in their original form and there has been much debate about why this is. One of the downsides of the escapement (said by McEvoy to be its Achilles' heel) is that any build up of dirt on the pallets had a significant impact on the rate of the clock.

It is an unfortunate fact, that the results of the trial have been misunderstood in the past and that this misunderstanding is in serious danger of becoming embedded. In his book English Precision Pendulum Clocks, Derek Roberts published a transcript of the trial results (with a shockingly large number of transcription errors) and wrote:

'Note that even at this time its going became irregular after just 10 weeks [days] because of "foul oil"; however its overall performance was excellent, remaining within the same second'.

In December 2021, Bonhams sold what they believed to have been the trial clock for £25,250 (Bohnams Catalogue). Seemingly building on what Roberts had written, the catalogue entry states of the trial:

‘Overall the performance was very promising. The regulator maintained a rate of to within one second a day, but not before a problem in the middle of June when the performance became erratic due to the accumulation of dirt on the pallets. Hardy had to clean the pallets and "the teeth of the swing wheel" (escape wheel). It took two days to do this and reset the clock when it ran until the end of August to within one second a day.’

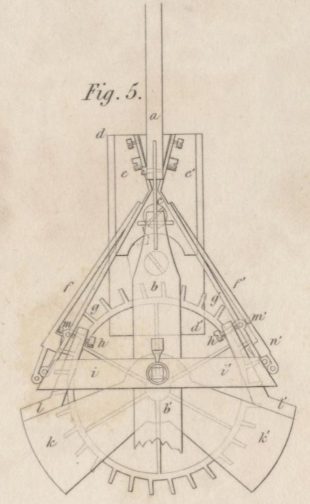

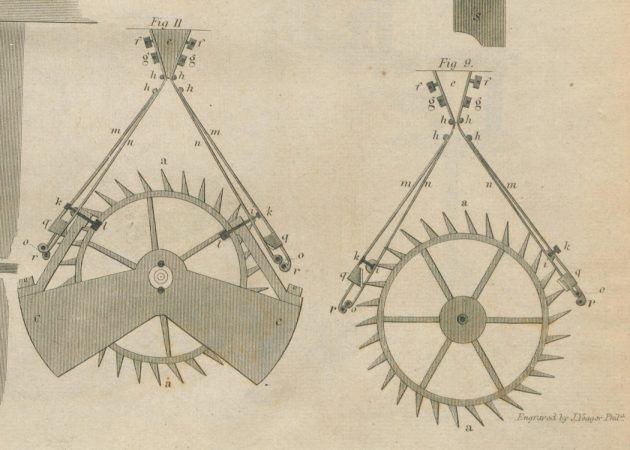

Contemporary descriptions of the escapement

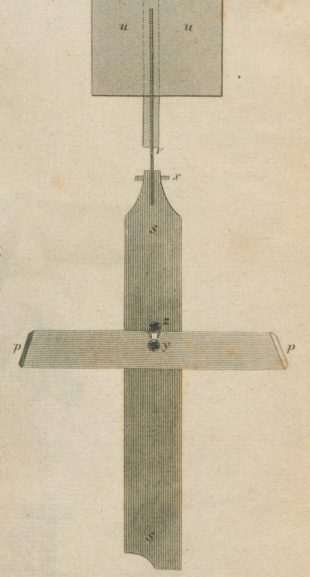

Hardy's Escapement. Detail from Plate 14 of Pearson's An introduction to practical astronomy (London, 1829). Copied by J Farey from plate 34 of Hardy's description in the Transactions of the Society Instituted at London for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce and engraved by E. Turrell. Reproduced courtesy of Robert B. Ariail Collection of Historical Astronomy, Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of South Carolina Libraries

Letter and description: Transactions of the Society Instituted at London for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce. Volume 38, (1820) pp.168–185.

At the end of the description, Hardy made the following somewhat ambiguous statement:

‘I think it proper to add, for the benefit of the time-piece and regulator makers, that I have enabled Mr. Thomas Leyland, clock-maker, of Prescot, in Lancashire, to cut wheels and pinions with teeth made truly epicycloidal, from patterns generated by myself, and also to make and fit up regulator movements complete.’

What he failed to state is who Leyland was authorised to make them for? We don't even know if he made them for Hardy himself.

There are at least 18 clocks known to have been made by (or for?) Hardy. They are listed in the appendix at the bottom of the page. Although all are very similar there are significant variations between them. These include the number of pillars linking the front and back plates (some have five and others four), the train count, the precise detailing of the dial and the positioning of the four screws fastening the dial to the rest of the movement. In many ways, the Greenwich Clock was an overspecified prototype for those that followed and differed from them in a number of significant details. A proper comparative study is long overdue, but is regrettably beyond the scope of this website.

In 1824, Ferdinand Hassler published a description of the two clocks supplied by Hardy in about 1813 for his survey of the coast of the United States. It included four figures which included drawings of the escapement. It is interesting to note, that they differ in significant details from those published by Hardy

Hardy's escapement as drawn from life at Greenwich by Ferdinand Hassler in 1812 and later engraved by J. Yeager. At some point later, Hardy seems to have modified the design as the escape wheel teeth have squarer ends in the designs he published in 1820. Detail from plate 6 of Papers on various subjects connected with the survey of the coast of the United States by F. R. Hassler (1824) Reproduced under a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 license courtesy ETH Z�rich

In 1816, William Pearson (1767–1847), bought a Hardy Regulator. A few years later he helped found the Royal Astronomical Society, and in 1826 he joined the Observatory's Board of Visitors. At the end of the 1820s he produced his magnum opus, An introduction to practical astronomy, in which he described Hardy's escapement and how it should be cleaned. His account and illustrations however were largely adapted (largely without acknowledgement) directly from the account given by Hardy in 1820. Links to the relevant pages are provided below.

Description: An introduction to practical astronomy, Vol 2 pp.306–8

Illustrations: An introduction to practical astronomy, Vol 3, Plate 14, figs 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Instructions on cleaning the escapement: An introduction to practical astronomy Vol 2 p.315

Hardy is said to be the first (British?) Clock maker to use accurately cut epi-cycloid shaped teeth on the wheels and pinions of his clocks. Details of how they were cut were initially published in 1822 by Thomas Gill in Volume 1 of his Technical Repository: and elaborated on in 1839 in Volume 1 of his Machinery Improved.

The delivery of the Greenwich Clock prior to Pond's arrival and an argument over the bill

What is very clear, is that the sort of information one would normally expect to find about the clock is not present in the minutes of the Council of the Royal Society as transcribed for Airy in RGO6/22. In particular, there is no record of any discussion between Maskelyne and Council about ordering a clock from Hardy. Nor is there a record of Maskelyne or Pond submitting Hardy's bill to Council for them to approve and then forward to the Board of Ordnance for payment in the normal way. Pond himself would have been aware of this procedure regarding the payment of bills before he became Astronomer Royal as he was present at the Council meeting on 13 December 1810 when Maskelyne submitted a set of bills for approval (RGO6/22/63). Either all the references to the clock were overlooked during the transcription process, or irregular procedures were being followed.

The minutes of the Council held on 23 April 1807 record that:

'a letter from the Secretary to the Board of Ordnance date March 23rd 1807 was read stating that the said Board had given orders that the Circular Instrument, and necessary alterations to the building of the Royal Observatory, recommended by the President and Council of the Royal Society should be immediately provided.' (RGO6/22/54)

There is no mention of the clock in the minutes of the meeting and neither the original letter nor a copy of it can be located so that the full text can be examined. Nor is there any mention elsewhere of the Board authorising the purchase of a new clock.

The exact date of Pond’s appointment as Maskelyne's successor is uncertain as is the date that the clock was delivered. The Navy Estimates for 1812 show that Pond was paid from 18 February 1811 (ADM181/20), the official announcement of his appointment being made five days later in The London Gazette (Issue 16457). However, he was unable to take up residence until 13 April due to the length of time it took Maskelyne's widow and daughter to move out.

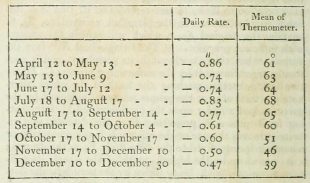

The Mural Circle was erected in 1812, with the first published observations being made on 11 June. A note Pond wrote in 1830 records that the clock was installed in 1811 and that 'its daily rate from April to the end of the year was remarkably uniform' (RGO5/222). Although Pond's note does not state when in April the measurements began, a table of the clock's rate published in Rees’ s Cyclopaedia in 1819 shows that it was up and running by 12 April. In other words, it was installed before Pond took up residence. Whether of not it was delivered before or after Maskelyne died is not known. What we do know however is that the pier on which the clock was to be mounted was in place by the autumn of 1809. In a letter to Hardy dated 13 September, Maskelyne wrote:

'You desired the pier built for receiving the clock bespoke of your for the new room, might not be painted; but I forgot to mention it in time, and they have now painted it, without my being aware of it. You will consider whether it will do any harm, and how long time it will take drying, & whether it will do harm, & if the paint should be scraped off? Pray urge Mr. Troughton to finish the pendulum.' (RAS/MSS/Add/5/7)

The letter is of interest on several counts. Firstly its incoherent nature. Secondly because it conveys a sense of urgency and thirdly because of the mention of Troughton making the pendulum (assuming that it is that it was for Hardy's clock rather than another clock at the Observatory or for pendulum swinging experiments). Given the letter's contents, one might reasonably expect the clock to have been erected long before Maskelyne died. On the other hand, there is no evidence that Hardy ever submitted a bill to Maskelyne for the completed clock, which suggests it was completed afterwards. Hardy's letter that was written in 1820 and accompanied his description of the escapement in the Transactions of the Society Instituted at London for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce also seems to imply that it was delivered afterwards.

William Hyde Wollaston, by William Ward, after John Jackson. Mezzotint, early 19th century. � National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence (see below)

‘Mr. Wm. Hardy having delivered a Bill amounting to £325 for the astronomical clock he has prepared for the Royal Observatory, and the Astronomer Royal having stated that the charge is much greater than was expected or thought reasonable by the Council of the Royal Society: I am directed to acquaint you therewith, and request you will move the Council to favour the Board with their opinion, what would be a reasonable sum to be allowed Mr. Hardy for the Clock alluded to.’ (RS/MS/172/146)

The letter was not acted upon until some twelve weeks later when it was read at what appears to be the next meeting of Council on 14 November. There it was resolved that 'Mr Hardy be desired to attend a meeting of the Council on Thursday next [21 November]'. There is no mention however of Hardy actually having attended in RGO6/22.

In light of Bank's relationship with Maskelyne from 1806 onwards, it is interesting to note what information the Council of the Royal Society did and did not include when they gave their opinion to the Ordnance as to 'what would be a reasonable sum to be allowed Mr. Hardy for the Clock' After a brief introductory paragraph, their report continued:

'That having examined Mr Hardy on the reasons & calculations of his charge of £325 for an Astronomical Clock; and then inquired of all such persons as they thought able to give them information respecting the just value of & proper prices for such Instruments. Hence they are opinion That Mr Hardy has in consequence of a misconception of the verbal directions given to him by the late Astronomer Royal unnecessarily incurred a considerable expense in executing those parts of the clock which have no real influence on the correctness of its going. He appears to have finished those parts almost as highly as the principal movements. The labour and expense thus bestowed are of little or no value to the purchasers of a Clock as a measure of time. That he has employed more jewel work, than usual, in making this clock, more than they believe has before been thought expedient in the construction of any clock whatever. That he has been so inattentive to the interest of his employers, as to suffer the tradesmen, of whom he ordered those parts of the clock which the clockmaker does not usually supply (the case for instance) to charge for their work prices as unreasonable as his own charge is deemed by the Council to be. That he has, in computing his charge for this clock, included the expense of some part of the tools with which it was made; a practice never customary with tradesmen of any kind, as the tools remain their property; and those of Mr Hardy have actually enabled him to make other clocks for the persons who now employ him. On considering the whole of the case, the general testimony of those who have inspected the Clock that it seems to be extremely well executed, and the report of the Astronomer Royal that it has gone with extraordinary exactness since it was put up in the Royal Observatory. The Council do resolve to recommend to the Board of Ordnance to pay Mr Hardy the sum of Two hundred guineas for the clock he has delivered; and they are of opinion that this sum, which is considerably larger than any that has been before paid for an Astronomical Clock, is a liberal compensation to Mr Hardy for his skill & labour in making the Clock as well as for the just and reasonable cost of the articles not furnished by himself.' (RGO6/22/69 & RS/MS/172/153)

The extent to which Banks was attempting to deflect blame away from himself and the Society for the Hardy fiasco by being economical with the truth is difficult to judge. Only one individual can be identified by name as having talked to Hardy – the clockmaker Alexander Cumming. Nowhere in either his report to the Society or the Society's report to the Ordnance is there any mention of a written contract with Hardy – so did one actually exist? The real elephant in the room however is the signed but undated itemised estimate from Hardy for £269 3s 6d. for supplying the Greenwich clock. Held in the Royal Society archives (RS/MS/372/152) rather than those of the Observatory, there is no reference to it in Cumming's or the Royal Society's reports, (nor seemingly in most modern accounts of the affair either).

Estimate of the Greenwich Clock

| To ten months, and two weeks workmanship, and time | £210-0-0 | ||

| Frames Mounting | 8-0-0 | ||

| Brass Plate | 6-10-0 | ||

| Wood work | 20-0-0 | ||

| Varnishing D.o | 1-0-0 | ||

| Pendulum and index | 8-10-0 | ||

| Weight, and pulley work | 1-11-6 | ||

| Dial place, and glass | 2-10-0 | ||

| Engraving D.o afresh | 1-0-0 | ||

| Jewelling | 9-10-0 | ||

| Porterage and carriage | 0-12-0 | ||

| £269 3 6 | |||

| charge - £325 [written in another hand] | W.m Hardy |

After interviewing Hardy, Cumming wrote to Wollaston on 19 Jan 1812. In his letter, he explained how he had met with Hardy (apparently at the Council's request and at the suggestion of Hardy) to discuss the terms of the contract. Although the Ordnance letter of 21 August 1811 could be construed as meaning that Hardy appealed over Pond's head directly to the Ordnance for payment, this does not appear to be the case, as Cumming wrote that Hardy 'said that he understood that his Bill was sent to the Tower, and he supposed it was to be paid' (RS/MS/172/149).

Alexander Cumming. Portrait by an unknown artist (detail) presented to the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers by his grand-nephew, John Grant in 1882

In the published letter of 1820, Hardy himself gave the following account of the agreement that had been made:

‘It was from the satisfactory performance of this clock [the one that had been on trial], that I was recommended by the Doctor [Maskelyne] to the Board of Ordnance as a fit person to furnish a clock on the same principle for the room in which the famous mural circle is placed, which circle was then making by the celebrated Edward Troughton. The order for the clock was unlimited in price, and directed me to consult the Doctor on every particular connected with it. I therefore waited on the Doctor to receive his instructions; his treatment to me was kind and hospitable, and he gave me every encouragement to exert myself, and to complete the clock in such a manner as to be durable and certain in its performance. As it was to accompany one of the most excellent instruments that ever was made, he wished the clock to be equally so in point of excellence. This excited me to use my utmost exertion, and to spare neither time nor expense in order to make it as perfect as possible. It was decided upon to jewel every action in the escapement and all the pivot holes. The teeth of the wheels and pinions were epicycloidal, and were all finished in the engine by cutters which I made for that purpose; and the whole of the clock was finished in a style equal to any of our first-rate chronometers.’

Having received a letter from the Ordnance that they were 'not disposed to allow the amount' of his bill, Hardy replied on 17 February 1812 asking 'for two or three superior chronometer makers' to arbitrate or 'to have permission to take back the clock' (RS/MS/372/150). Two days later on 19 February the Ordnance forwarded a copy of Hardy's letter to Wollaston and asked for the opinion of the Royal Society on the matter (RS/MS/372/151). Impatient for a reply, the Ordnance wrote again on 3 March asking for the Society's response (RS/MS/372/148). Two days later, on 5 March, the letter was discussed at Council, who somewhat scathingly:

'Resolved. That the Council of the Royal Society do recommend to the Board of Ordnance that Mr. Hardy's proposal of submitting his bill to a reference be consented to; but since the matter iin question between the Board of Ordnance & Mr, Hardy is a clock and not a chronometer, the Council deem it a necessary condition that the referees be not mere Chronometer Makers but Clock makers.

Resolved Further. That the Council of the Royal Society would highly approve the nomination of Mr. Alexander Cumming who was originally named to them by Mr. Hardy as a referee peculiarly qualified to judge of the merits and value of his workmanship.' (RGO6/22/70)

At this point, the record peters out so it is not known for sure how the situation was resolved. Clearly Hardy did not take the clock back as it remained at the Royal Observatory. It is usually stated that Hardy was paid 200 guineas for the Greenwich clock. This is despite the fact that no evidence has been uncovered to verify that this was actually the case. The best that can really be said is that he was probably paid 200 guineas (£210).

Known prices charged by Hardy or paid to him for the clocks he supplied

Price |

Ordered |

Delivered |

Supplied to |

Ref: |

||

| £2101 | 1808 | 1811 | Royal Observatory Greenwich | See above | ||

| £150 | 1809 | ? | Garnethill Observatory, Glasgow |

Myles (1982)2 |

||

| £125 | 18 | 16 | Rev. William Pearson | Allix 1990 | ||

| £105 | 18 | 22 | Royal Observatory, Cape of Good Hope |

RGO14/7/3913 |

||

| £150 | 18 | 25? | Rev. Thomas Hussey | 1982QJRAS..23..552D4 |

1. This price assumed to have been paid (see section above)

2. Order either cancelled or clock repossessed c.1814

3. See also RGO14/48/173 & RGO14/48/58

4. Said by Hussey to be one of Hardy's most expensive ones

Hardy's astronomical regulators are known to have been expensive and tended to cost more than those by other makers. But exactly how his prices compared is difficult to judge as figures are not generally available. One that is known, is the £120 paid for the 8 day regulator by Grimaldi & Johnson, which was acquired for the Observatory in 1819 (RGO6/22/100). Clocks could however be obtained for much less as can be seen from the November 1817 Catalogue of Optical, Mathematical, and Philosophical Instruments made and sold by W. & S. Jones where the price of an astronomical clock, with mercurial, or other compensating Pendulum is listed as £47.5s. to £84 depending on the jewelling.

Further details of the Hardy clocks listed above can be found in the appendix at the bottom of the page.

The origin of some of the brass used by Hardy

The cross bar of the pendulum. According to Hassler, the ends (marked p,p) on the clocks supplied to him were made from brass once owned by John Harrison. Adapted from Fig.8 from Plate 6 of Papers on various subjects connected with the survey of the coast of the United States by F. R. Hassler (1824) Reproduced under a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 license courtesy ETH Z�rich

The first was made by Thomas Gill on 14 July 1818 in his article titled On English and Foreign Copper, Zinc, and Brass that was published in volume 12 of The Annals of Philosophy.

'The late Mr. Harrison made his celebrated time-pieces of old Dutch pan brass; and Mr. Hardy was recently furnished with some of it by the Board of Longitude, in whose hands it had been preserved from the time of Mr. Harrison, to make a timepiece with for the Royal Observatory at Greenwich.'

The second, also by Gill, was published a month later when he made a correction to the above writing:

'Having seen Mr. William Hardy since the publication of my paper, "On English and Foreign Copper, Zinc, and Brass," in your last number of the Annals, he informs me that he had the old Dutch brass of which he made the wheels for the time-piece at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, not of the Board of Longitude, but of a Mr. Frodsham; and paid him for it at the rate of one guinea per pound! – a proof of the very high estimation in which it is held by watchmakers.'

The third was made in 1823 by Hassler himself who said of the two clocks that Hardy made for him:

'Only the scapements are jewelled in these clocks. The other pinion holes are boxed with brass taken from a piece brought to England from Bengal as a sample, which was given by the Board of Longitude to Mr. Harrison, the first inventor of chronometers. At his death, Mr. Hardy bought it, and uses it with the greatest economy for such purposes. The ends p,p [see diagram] of the cross bar on the pendulum are also lined with this brass.'

The historic locations of the Greenwich clock, the method of mounting and the design of the case

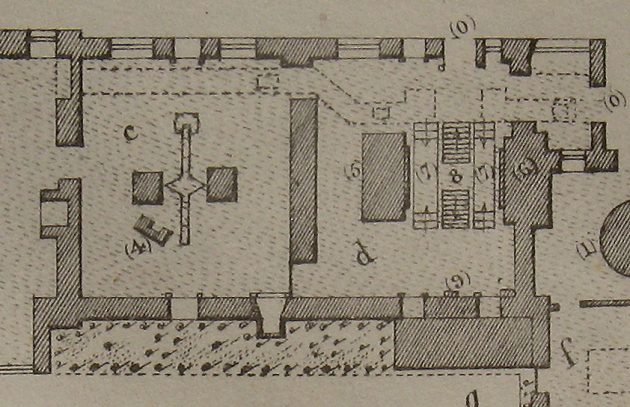

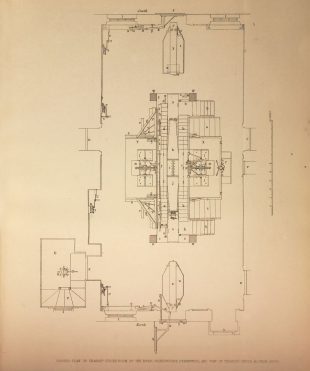

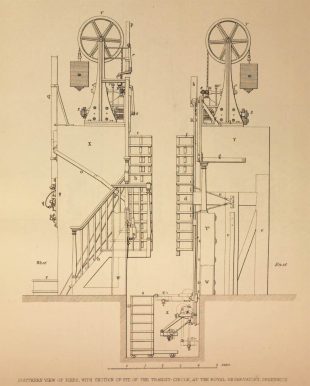

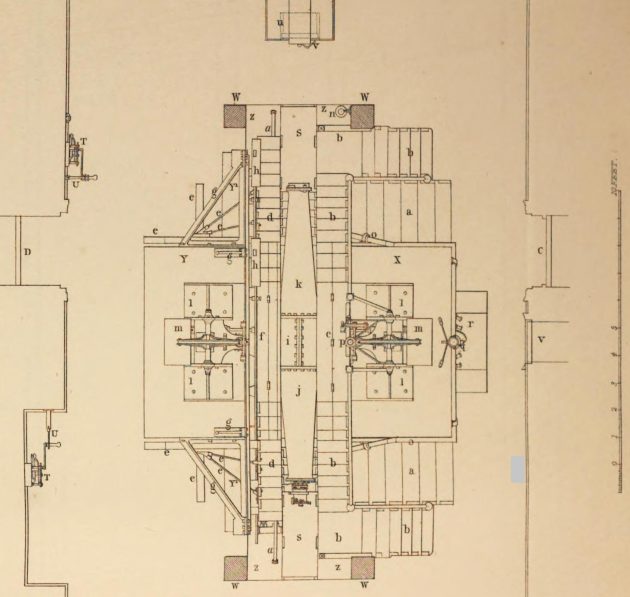

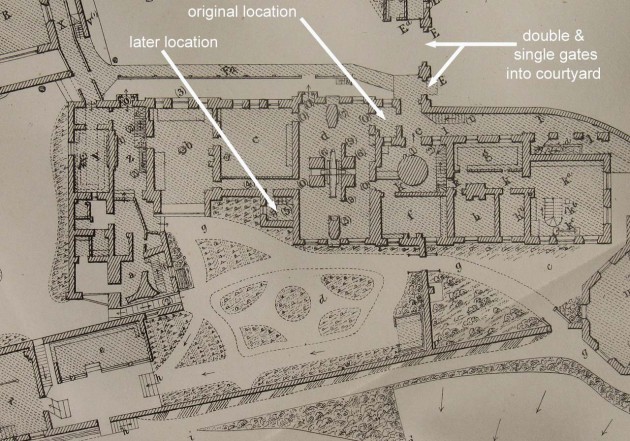

Although Pond published an engraving of the Mural Circle in his first volume of published observations, he failed to show the clock or where it was mounted relative to the telescope. The Circle Room as shown on the 1831 Observatory plan (RGO6/45) shows the room as it was some seven or more years earlier and predates the construction of the pier for the second Mural Circle (which began in January 1824). It shows an unlabelled structure, presumed to be the clock pier, close to the Circle Room wall immediately to the east of the centre of the Troughton Mural Circle. When Airy drew his manuscript plan of the Observatory in 1846 (ADM140/426), it included the pier for the second mural circle on the site previously occupied by the clock, and a new and rather smaller clock pier located against the south wall and roughly equidistant from the two Mural Circles to which a journeyman clock was originally fitted.

Detail from the plan published in 1847 as an addendum to the 1845 volume of Greenwich Observations (north at the top). It is based on Airy's 1846 manuscript plan (ADM140/426). Key: (c) Transit Room. (d) Circle Room. (4) the pier for the Transit Clock (Hardy from 1823–1850) – note the recess cut into it. (5) the pier for Troughton's Circle. (6) the Pier for Jones's Circle. (7) the pits for the convenience of reading the lower microscopes of the Circles. (8) the stage for reading the upper microscopes of the Circles. (9) the pier for the Circle Room Clock (probably erected here in 1823 or 1824 around the time Hardy was moved to the Transit Room). The large shaded area on the opposite side of the wall to (9) is marked on the manuscript plan as a buttress

The earliest evidence for how the clock Hardy was originally mounted comes from Hardy himself in the letter that he wrote for publication in 1820:

‘The Doctor [Maskelyne] being sensible of the great importance of fixing up the clock upon a material that should be permanent and immoveable, I suggested that it should rest upon a strong brass plate screwed fast to the top of a stone pier, in which a recess or channel might be cut out to receive the weight and the pendulum, which was adopted.’

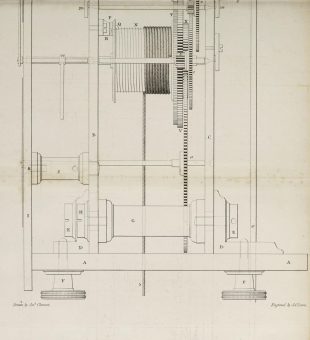

Detail of plate 35 accompanying Hardy's description of his escapement. Drawn by Joseph Clement and engraved by James Davis., it shows a side view of the lower half of a movement that was possibly drawn from life in Hardy's workshop. The dial is on the left. (A) is the brass plate (the seatboard) on which the movement rested. It is about half an inch thick, several inches deep and more than a foot in length. At Greenwich, the seatboard spanned the top of the recess of the stone pier to which it was bolted. It contained piercings through which the pendulum (x) and the cord (5) which supported the driving weight passed. Reproduced from Transactions of the Society Instituted at London for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. Volume 38, courtesy of the Wellcome Library & Internet Archive

William Ellis, who started work at the Observatory in 1841 gave this brief description of the clock in his reminisces which were published in The Observatory in 1897:

'The transit clock stood then encased in a stone pier, the pendulum being visible through a plate of glass fixed in front, and if my memory does not deceive me, the letters O and E were painted in black on the stone, one on each side of the glass front.'

Taking into account what both Hardy and Ellis had to say, it would seem either that the movement as well as the pendulum was encased in the stone block or that the clock had a fairly conventional hood, possibly similar to that of the Brisbane and Garnethill clocks.

With its integral stone pier, the Greenwich Clock would not have been easy to move and this might well explain why instead of moving it to the Transit Room in 1816, Pond continued to use Graham 3 there. Eventually, starting in 1821, he dismounted Graham 3 and installed a series of transit clocks in quick succession (some or all of which appear to have been supplied on a trial basis), starting with a clock by Molyneux and Cope. Finally, in late 1823, with work shortly to begin on erecting the pier for the second circle, Pond had Hardy moved into the Transit Room. On 4 November, he recorded in Greenwich Observations: 'Took down the temporary transit clock, and removed Mr. Hardy's clock from the circle room into its place.' How long this took is not clear as no further observations were made until 9 November. Given that observations were made with the Circle on 6 November, it sounds as though the move took a minimum of three days. Given that in 1816, it took no more than eleven days to increase the height of the piers on which the Bird Transit Instrument had been mounted and to get the new Troughton Transit Instrument installed in its place, it is likely that as well as the clock being moved in 1823, the pier was as well, especially as the 1831 plan implies that the two clock piers had the same footprint and the 1846/7 plan (above) shows the pier with a recess cut into it. Further evidence that the pier was moved comes from Pond in his explanation to the Visitors of how Dent's name came to be inscribed on the dial in 1830. In it, he wrote:

'Another clock could not be permanently substituted, as the stone pier is constructed expressly for Mr. Hardy's Clock, so that in this emergency no method of proceeding with the observations appeared so advisable of availing ourselves of Mr. Dent's offer. (RS/MS371/58)'

Normally when things needed doing to the clock, Hardy was involved and Pond recorded this in Greenwich Observations with phrases like 'Mr. Hardy took down the Clock to be cleaned.' or 'Mr. Hardy put up the Clock, and set it nearly with sidereal Time.' Although Hardy was not mentioned by name in the 4 November entry, there are two reasons to believe he was there. Firstly, because on 22 November Pond recorded that Hardy had stopped the clock and fitted a new second hand (presumably because the original was damaged during the move). Secondly because in 1824, Thomas Gill wrote in his Volume 5 of his Technical Repository:

‘We were exceedingly gratified by Mr. Hardy's information, a few days since, that the teeth of the wheels and pinions of his time-piece at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, were lately examined with magnifiers, by several of our most scientific men, and that not the slightest appearance of rubbing could be perceived upon them, after thirteen years' wear!’

going on to say:

'This is, indeed, a most satisfactory example of the value of the epicycloid, when applied with accuracy to the teeth of wheels and pinions.'

Having been moved, the Greenwich Hardy was to remain in position for just 27 years before being moved again. Being a systematic man, Airy decided that he wanted observations with his new Transit Circle to commence on 1 January 1851 or as soon thereafter as weather permitted. To this end, he had Hardy moved from the Transit Room to the Transit Circle Room towards the end of December. He recorded the following in the 1850 volume of Greenwich Observations.

'December 27, 0h. The transit-clock (Hardy) was removed to the Transit-Circle Room, and a clock by Arnold (A2) was used in its stead.'

What he did not report was that whilst removing the pendulum 'the spring' was broken and a new one had to be specially made in a great hurry by Dent's team (RGO6/723/151–2).

Although Airy informs us that Hardy was placed in a recess built into the brickwork of the pier supporting the south collimator of the Transit Circle, he failed to mention that the upper section where the movement sits is around 18 inches wide, whist the lower section below the seatboard is roughly 14 inches wide. Nor did he mention that a massive cast iron seatboard was substituted for the brass one. In its new location, the movement was no longer accessible from above or from the side. On the assumption that Hardy made the clock broadly in accordance with his published plans, this would also have necessitated altering the way in which the pendulum was suspended (more on this below).

The cast iron seatboard is slightly less wide than the upper part of the recess. Rather than being of a uniform thickness, it has two bracing ribs than run from side to side across the bottom. As a result, the thickness varies from around ½ inch to more than three inches. The corners of the left and right hand edges extend beyond the central section and taper inwards. This presumably made it easier to remove when required. It is not currently known if the seatboard originally sat directly on the brickwork, nor if it was held in place solely by its own weight. Nor is it known if there was some kind of locating lug to ensure it was always returned to the same place.

Airy arranged things so that the dial was in clear view of the observer siting in the pit of the instrument and looking towards the south (see image at the top of the page). As a result, most of the clock was below ground level, with the dial itself being about a foot above the floor of the room. When Airy published his description of the Transit Circle in Appendix 1 of the 1852 volume of Greenwich Observations, he failed to mention how the pendulum was accessed for adjustment and maintenance. If as originally conceived the section of flooring between the collimator pier and pit was removable, this is no longer the case, the floor having been replaced at least twice since the 1960s under the stewardship of the National Maritime Museum.

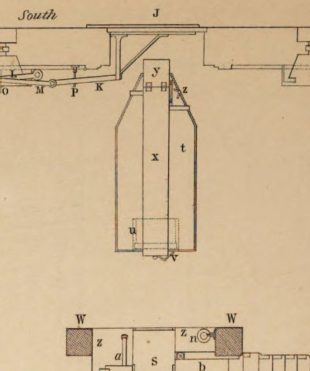

Ground plan of the Transit Circle Room and view of the Transit Circle etc. from above. Adapted from Plate 3 of Airy's description of the Transit Circle published as Appendix 1 of the 1852 volume of Greenwich Observations

Detail, showing the location of Hardy and the lamp used to illuminate it (key below). Reproduced courtesy of the Munich DigitiZation Center (MDZ) and the Bavarian State Library (BSB).

Key (adapted from Greenwich Observations): Complete Key to plate 3.

| t. | The pier for the south collimator. Made of brick, it was covered with a slab of sandstone. | |

| u. | (Dotted lines,) the recess in the brickwork of the pier below the stone slab, in which the transit clock is placed. | |

| v. | A small projection from the clock case, in which a chronometer was placed when it was being compared with the transit clock (no longer present). | |

| n. | A gas light with its smoke chimney fixed to W for illuminating the transit clock (no longer present). |

|

| x. | Wooden box covering the collimator | |

| W. | Pillars supporting the roof. |

In its new location Hardy was particularly vulnerable to damp, so much so, that in 1861/2 Airy was to tell the Visitors:

'The steel-work of the Transit Clock (which is almost buried in the South Collimator Pier) had been found extremely liable to rust; but holes have been made through those parts of the Pier which encase the clock, permitting a much more free ventilation of the clock than it formerly received: and the rusting seems to have been in great measure prevented.' (1862 Report)

Whilst an improvement, the dampness was still clearly problematic as in 1868 Airy was to tell the Visitors:

'I have given a new form to the head of the clock, for admission of small tin boxes in which a few lumps of quicklime will be placed, in order to keep the air about the wheel-work in a state of dryness.' (1868 Report)

The following year he informed them that the quicklime was changed once a month (1869 Report). After this, there is no further mention of either quicklime or the tin boxes, meaning that it is not possible to know if and when the practice was discontinued.

The damp however remained a problem. In 1874, the clock was absent from the Observatory for around ten to eleven weeks while being refurbished. Having 'become exceedingly rusty', it was absent again in 1878, this time for just over eight weeks as (more on these absences below). Later, in 1905, the then Astronomer Royal William Christie noted in his Report to the Board of Visitors:

'The Clock Hardy, which was much rusted owing to damp weather, has been cleaned by Messrs. Kullberg, who have made alterations in the case to protect the clock from damp as far as possible.'

What the alterations were was not recorded. It is possible that further research in the archives may yield details, but such work is currently beyond the scope of this article.

Regrettably, no records have yet been located that show how the seatboard sat within the recess prior to the clock being put on display by the National Maritime Museum in 1967. Conservation photos taken in 1969 show that at that time the brickwork surrounding the clock was painted black with the seatboard seemingly sitting directly on the brickwork below. At some point, possibly around 1990, when an attempt was made to increase the running time of the clock from 3¾ days to 8 days (more on this below), the recess was lined with what appears to be plywood. The seatboard no longer sits directly on the brickwork but on some kind of a wooden plinth that sits between them. Its left and right hand edges are now concealed by the lining that rises vertically above it. As a consequence, the dial is around 5cm higher than it was before and the seatboard can no longer be easily removed from the recess. The plywood also prevents an inspection of the brickwork for evidence of where the holes may have been made in 1861/2. It should also be noted that the holes have long since been plugged on the outer surface of the pier and there is little indication of where they may have been – though in racking light, one possible location can be picked out on the eastern side.

The piers which supported Troughton's Transit together with the pier on which the transit clock had been mounted were removed at the start of 1851. When the Observatory was turned into a museum, replica piers were erected on the site of the originals. The replica clock pier is rectangular in section and tapering towards the top, with a vertical face on which to mount the clock. It is suspected it was modelled on that shown in a late eighteenth century drawing of the Transit Room, when Graham 3 was mounted there. Purchased in 1966 (Object ID: PAF2956), a year before the building which houses the telescope was opened to the public, it was drawn by John Charnock, probably in the 1790s. The Museum however had a problem on its hands. Hardy, which was loaned by the Astronomer Royal was (rightfully) retained in its 1851 position with the Airy Transit Circle.

The dilemma the Museum faced, was what clock to mount on the replica pier given that it did not own Graham 3 which had been retained by the Royal Greenwich Observatory (RGO). The RGO also retained Graham 1 and Graham 2 until its closure in 1998 when all three being transferred to the museum. To solve its problem the Museum borrowed a Shelton clock from St John's College Cambridge. It remained on loan to the Museum from 1966 until 1992. Today (2023), rather than supporting Graham 3, the replica pier in the Transit Room supports a clock by Hardy which although never used at the Observatory was purchased by the Museum in 1980 (Object ID:ZAA0606). Known as the Jenson Hardy after a previous owner, not only is it mounted in an entirely different way to the Greenwich Hardy, the detailing of the dial is also different. It also lacks the brass seatboard, being supported instead by one of wood (view image) and has an escape wheel of a different design. Interestingly, in 1967, the Museum also borrowed the regulator by Hardy that had been bought in the 1820s by the Cambridge Observatory (now part of the Institute of Astronomy). It was returned to Cambridge in 1981 following the Museum's purchase of the clock mentioned above. It now forms part of the collections of the Whipple Museum (Accession Number 2800).In 1975, volume 3 of Greenwich Observatory by Derek Howse was published. Although Howse was a curator at the National Maritime Museum and a key player in the 1960s in converting the Observatory into a museum, he seems to have believed that the clock was originally supplied and mounted in a conventional wooden case. In the book, he provides a table of key dates in the history of the clock. Against the year 1850 he has recorded 'Movement taken out of wooden case and mounted in Transit Circle Room pit as transit clock'. His successors seem to have taken much the same view and much the same information is currently (2023) given on the Museum's website. It seems probable that Howse was not aware of Hardy's 1820 letter.

When Hardy supplied his clocks to (some?) purchasers, he also supplied instructions on how they should be mounted. Those republished by Pearson began:

'The case must be fixed up to a solid stone pier by the four blocks and screws. The screw holes must be made in the back of the case, where they are marked. The brass plate on which the clock is seated is to be made perfectly horizontal, by placing the spirit-level betwixt the pencil lines drawn thereon. ...'

By contrast, in the description published in 1820 Hardy wrote something completely different:

'AA, plate XXXV, represents the edge of a horizontal brass plate [the seatboard], which must be fixed on two brackets firmly screwed to a stone pedestal or wall, and quite independent of any part of the case of the clock.'

The three different mounting methods published in different locations at different times perhaps help explain the confusion that has existed for so many decades about the way in which the Greenwich Clock was mounted.

The dial

Measuring 297mm across and 3mm thick, the dial was originally silvered brass. The large outer dial indicates the minutes, the small upper dial the seconds and the small lower dial the hours. At some point (date currently unknown), the dial was painted white. This was first vaguely mooted in February 1851 just eight weeks after the clock had been moved for use with the new Transit Circle. Writing to Dent, Airy explained:

'We find that with our new Transit-Circle, in the use of which the observer is somewhat more distant from the clock than he used to be, we have some difficulty in reading the clock-face. This arises from the surface of the clock face; which has been turned on the lathe, and bears the circular furrows produced by the turnings, and always shows a bright line across it. To get rid of this, I wish to know whether you could alter the quality of the surfaces, so as to deprive it of all regular lines. We want a surface, brilliantly white if possible, but at the same time, dead in respect of reflexion, like a surface of flattened paint.

At the same time we want a stronger second band [hand?], and perhaps some of the divisions stronger. ' (RGO6/724/101)

Dent replied explaining that the dial could be made 'dead silver white' and that when varnished would retain its colour. He also stated that the engraving could be made stronger, but that it would take several days to do (RGO6/724/102). Dent's plan appears to have been put into action. In the 1851 volume of Greenwich Observations, Airy recorded that the clock 'was stopped for the purpose of having its dial plate resilvered and made dull to prevent reflexion on its surface'. It was absent from the Observatory from 28 February – 10 March. It would seem however that the dial was still prone to discolouring as a result of tarnishing because when Dent was asked that June if he could make the beat of the clock louder, there was a delay in returning the clock because as Dent explained in a letter to Airy, he had 'found a frenchman to silver the dial plate and varnish it so as to keep its colour' but that he (the frenchman) had taken longer to do the work than promised (RGO6/724/124). The underling of the word varnish by Dent suggests that however the surface was dulled earlier in the year, it was not the result of it being varnished.

Conservation photographs taken in the 1960s show that over the years, the markings around and beneath the winding hole (of the by now painted dial) had been worn or wiped away. This included the pair of outer tram lines of the seconds dial between the 34 and 40 marks and the outer circle of the hour dial between 19.5 & 22.5. The outer circle of the hour dial was also missing between 13.5 & 14.5, whilst the inner circle was missing between 13.5 & 18.5 and 20 & 22.5. The y of Hardy and the numeral 22 on the hour dial also showed signs of crude retouching prior to the dial undergoing conservation treatment at the National Maritime Museum in 1984. Other areas may also have been retouched prior to 1984, but it is not possible to discern this from the photos. What caused the loss is unclear, but the Museum thought that it may have been caused by contact with lubricant that had been subsequently wiped off. This could have occurred, if, as is believed to be the case, lubricant had been applied though the winding hole and had run down the dial.

When the dial was painted the form of Hardy's original engraving is thought to have been retained. It is suspected however that during the 1984 conservation work, the y of Hardy (much of which was missing) was not restored to its original painted form. In its present form, it is quite unlike those that are found on Hardy's other regulators. When Dent changed the clock's escapement for one of his own in 1830 (more on this below), Pond records that he added the following inscription: 'New deadbeat Escapement &c by Dent London A.D. 1830.' (RS/MS/171/58). This is not what is recorded on the dial today, the inscription being an abridged version and missing the words &c., London and the date. Perhaps Dent's inscription as originally engraved was aesthetically unpleasing and later altered for this reason.

The dial has nine drilled holes of varying diameters: four for securing the dial, three for the hands, one for the winding key and one viewing aperture which was cut in 1854 when the clock was adapted for use with the new chronograph and a wheel of 60 teeth was fixed on the escape-wheel-axis. The idea of the hole was to allow the momentary contacts of a set of galvanic springs to be observed as the teeth passed in succession.

There are also two segmental apertures in the seconds dial that have been plugged with brass plates soldered into position. Located between the 10 and 20 and the 40 and 50 marks, their position can just made out in the image above. Probably made by Dent in 1836 when Airy asked him if he could make the beat of the clock louder, they may also have been made in 1851 when Airy asked him if he could make it louder still. They were possibly closed in 1854 following the addition of electrical contacts which rendered most eye and ear observations with the clock obsolete. See below for information on these two sets of alterations regarding the loudness of the clock.

When writing to Dent in 1854 about the creation of the viewing aperture Airy suggested it should be placed in the seconds' dial 'either between 10s and 15s or between 15s and 20s'. He also suggested that the hole should be closed with 'either a door or a glass' adding 'perhaps a door like a plug is best' (RGO6/727/251). In the event, as can be seen in the photo above, neither of these positions was chosen, perhaps on account of the pre-existing segmental aperture. Nor was any kind of door or covering seemingly added. The following year in a letter written to Dent on 19 June (1855), Airy wrote:

'The window in the dial Plate of the Transit Clock may be made much larger. It may be carried quite across the 15s line and nearly to the 10s line, so that we can see the whole length of the galvanic springs.' (RGO6/729/168)

Looking at the dial today, it would appear that if the window was made larger, it was by rather less than Airy was suggesting. Perhaps Dent was loathe to cut into the plugged aperture on the basis that in doing so, the plug might break away and damage the dial.

Dust covers

Although later clocks by Hardy were supplied with internal wooden dust covers such as the one shown here, it is not known if such a cover was supplied with the Greenwich Clock. Its movement does however appear to have had cover plates (now missing) that were screwed to the sides and top, the evidence for this coming from the presence of screw holes drilled into the edge of the front and back plates (which were 7mm thick). It is not known if they were original or added later. Nor is it known when they were removed. The 1984 conservation report also states that a cover plate 'seems' to have once been present on the bottom of the movement, but does not state the evidence for this. Since the front and the back plates sat directly on the seatboard, and assuming that the statement was not made in error, it is not clear why a cover plate would have been fitted in this location.

Depending on exactly how Hardy had originally mounted the Greenwich movement, it may have been possible to examine it without the need to dismount it. Once the Clock had been moved for use with the Transit Circle, it most definitely wasn't possible to examine the movement without completely dismounting it. This would have been true whether or not dust covers were fitted.

The method of cleaning Hardy's clock

Cleaning the escapement was not straight forward. Although Hardy supplied clients with instructions on how the cleaning should be done, together with a pair of wedges that needed to be used in the process, these seem to have been largely lost or forgotten about as the years went by resulting in incorrect procedures being adopted and the escapement damaged. The following was transcribed and published by Pearson from the instructions supplied with his clock:

‘In order to take down the clock to be cleaned, first take off the pulley-weight; then relax the auxiliary springs, and put the wedges beneath the escapement-springs, as before mentioned; loosen the side screw in the bar, take off the pendulum with care, and seat it in the middle of the bracket inside the case, so that it does not touch the pins of the escapement at the top; then take the clock from the case, and remove the escapement entire, by taking out the long-headed screw in the middle of the cock; then carefully clean the faces of the pallets and detents. There must be no oil put to the cross piece on the pendulum, and very little to the pallets of the escapement. The other parts of the clock-work are the same as in common.’

The Movement, the driving weight and the duration of the Greenwich Clock

The first alteration to the Clock came as early as 10 January 1813. The published observations tell us that on that date: 'Before the passage of αAndronodӕ Mr. Hardy put a new weight to the clock.' Unfortunately, no details are known as to how it differed to the original weight. Over the years the driving weight and its configuration appear to have been further altered at least once and possibly three times.

The following description is thought to show how the Clock was configured when it underwent conservation work in 2010. It is taken from the Royal Museums Greenwich website:

‘The movement has exceptionally thick (7mm) arched brass plates [that] are united by five heavy pillars riveted to the backplate and secured by domed blued steel screws with shouldered brass washers. The finely constructed six-wheel train is driven by [a] brass cased weight with integral pulley and triple pulley system to compensate for the short drop of the pendulum chamber. The double line runs on a turned barrel with a sprung C-shaped stop iron mounted to the front flange with a chamfered push piece lying across the nineteenth turn. The barrel is also fitted with Harrison’s maintaining power, a great wheel and a second wheel driving the large hour wheel. All wheels have six straight crossings and are of light construction. The dead-beat escapement with jewelled brass pallets is mounted on the backplate; a sixty-tooth contact wheel with one blank division is mounted to escape wheel arbor between the frontplate and the dial with corresponding view aperture cut into the dial plate.’

In his later regulators Hardy adopted the practice of screwing rather than riveting the pillars to the backplate. The only other examples that have been confirmed as being riveted are the Hardy in the collections of the National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors, Inc in America and the Garnet Hill Regulator. The Brisbane Clock also seems a likely candidate, but no information has been made available as to how the pillars have been secured and no photos are available.

Other information about the movement of the Greenwich Hardy in its current form is as follows:

Barrel grooved for 20 turns.

Train count: 140 128/14 120/16 30/16

Wheel concentric with Great wheel 75. Wheel carrying hour hand 180.

The 1984 conservation report noted: 'Bottoming wear noticeable in all pinions'.

In 1836, Airy asked Dent to make the beat of the clock louder. The correspondence between Dent and Airy suggest that the weight and possibly the pulley system was altered at that time. On 2 December Dent wrote:

'I must then have a weight made with the pulley introduced into it - as it is now, it must be wound on the 7th day otherwise it goes down, and by the introduction of a pulley as stated, it will go the eight days.' (RGO6/715/19)

A new weight may also have been made in 1851 when Dent was asked for a second time to make the clock louder. Writing to Dent on 28 June Airy asked:

'I wish to know whether you think there as any objection to increasing the drop of the escape-wheel-teeth. If you think this may be tried, it would probably be worth while to make a new anchor and pallets, and put a heavier weight on the clock' (RGO6/724/119)

Dent concurred and to this end the clock was removed on 2 July for the work to be carried out. There is no record however to confirm whether or not a heavier weight was provided (RGO6/724/124 & Greenwich Observations 1851).

Conservation photographs taken in 1969, show a weight with a hook on the top hanging from a single pulley unit. The clock Hardy made for Brisbane (which dates from c1815) has a similar arrangement. Other clocks by Hardy for which images were available (three in total) show something different. All show a cylindrical weight with a pulley built into it. In Francis Baily's Clock and the Jensen Clock, the top of the pulley appears to be flush with the top of the weight. In the Cape Clock, it appears to be slightly lower.

Prior to 1864, Airy indicated in the Introductions to the volumes of Greenwich Observations that the Clock was wound once a week on a Monday. From 1864 onwards, he recorded that it was wound twice a week on Mondays and Thursdays, though he didn't indicate why. We do know however from the published observations that the Clock was taken down on 29 April for cleaning and bought back into use on 3 June, suggesting that this may have been when the switch over occurred. However, there is nothing in the correspondence with Dent to indicate that any alterations were made that necessitated such a change (RGO6/742/119&120).

Rate sheets from the National Maritime Museum from 1984 and 1985 record that the clock had a duration of approximately 3¾ days. In 1986, designs were drawn up 'for rendering the Hardy Transit Clock 8 day going'. One element of these was a newly designed driving weight. The conservation records do not show the existing arrangement at that time. Later records seem to suggest that the plan was put into effect in 1993, but there is no clear statement about this. The design does not appear to have been successful as rate sheets for 1993 and 1994 record the duration as 6 days, 23 hours and 15 minutes. This figure however was revised upwards in February 1995. In practice however, the clock frequently stopped between its weekly windings and in mid-2006, the figure for the exact duration was revised once again; this time to 'Approx 7 days only'.

The Museum records indicate that there are two weights now associated with the Clock, but give no further information other than their dimensions (but not their weight). Their object ID's are:

- ZAA0591.1 which appears to be the one that was use in 1969

- ZAA0591.8 which is shorter and tapers towards the top. It appears to be the weight that was designed in 1986

The pendulum

As supplied by Hardy, the clock came with a mercurial pendulum. According to the entry in volume 26 of Rees's Cyclopaedia, which was published in 1819, a Mr. Lowe of Islington calculated the size of the glass vessel for the mercury and that depth to which it needed to be filled (see also). The first modification came in 1828 when: 'Mr Hardy applied a new glass cylinder to the pendulum of the clock containing a column of quicksilver nearly half and inch longer than the former.' (Greenwich Observations,1828).

The present pendulum is a compensated one of zinc & steel. The earliest reference to Hardy having such a pendulum in the Observatory's own publications comes in the Introduction to the 1908 volume of Greenwich Observations and was repeated in the volume for 1909, which was the last volume to have an Introduction. After this date, there appears to be no further mention of the pendulum in the published output of the Observatory.

The pendulum mounting was altered when the clock was moved from the Transit Room into the recess in the collimator pier of the Transit Circle in December 1850. In the new arrangement (which remains) the pendulum is suspended from a heavy cast iron Troughton frame mounted on the cast iron seatboard which is roughly 18 inches wide. In its new location, rather than being fitted with a removable hood, the covering above the movement was an immovable sandstone stab. By altering the suspension arrangement, the likelihood of damaging the movement would have been considerably reduced.