…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

People: William Richardson

| Name | Richardson, William |

||

| Place of work | Greenwich | ||

| Employment dates |

12 August 1822 – 30 October 1845 (dismissed) (RGO5/233/7 & RGO6/24/103) | ||

| Posts | 1822, Aug 12 |

Appointed as additional Second Assistant |

|

| 1835 |

Richardson’s post re-titled as Third Assistant |

||

| Born | 1797, Feb 2 |

Pocklington, Yorkshire |

|

| Died | 1872, Mar 23 | Pocklington, aged 75. (The York Herald, Thursday 30 March 1872, p8) | |

| Family connections | Married Ann Rogerson, sister of William Rogerson | ||

| Known addresses in |

1822–1826+ | 16 Park Row, now demolished (RGO6/1/55v & 56r & rate books) | |

| Greenwich | 1830–39 | Royal Circus Street: originally known as Gang Lane and now as Circus Street. House probably demolished in the 1880s to make way for a railway extension (RGO6/72/19 & rate books) | |

| 1841–45 | Royal Hill / Peyton Place, now demolished (see below) |

||

| |

|||

| Life post Greenwich | Occupation and address | ||

| (from census returns) | 1851 | Proprietor of Houses. Market Place, Pocklington | |

| 1861 | Proprietor of Houses. Market Place, Pocklington | ||

| 1871 | Retired Astronomer. Paramatta Villa, Pocklington | ||

William Richardson brought both honour and shameful publicity to the Observatory. Born in the town of Pocklington in Yorkshire, he was recommended for the post at Greenwich by the instrument maker Troughton (RGO6/72/223). He was one of two Additional Second Assistants taken on in 1822. The other was Thomas Glanville Taylor the 18 year-old son of the First Assistant Thomas Taylor. Their appointment doubled the number of assistants at the Observatory from two to four.

Friends from the north

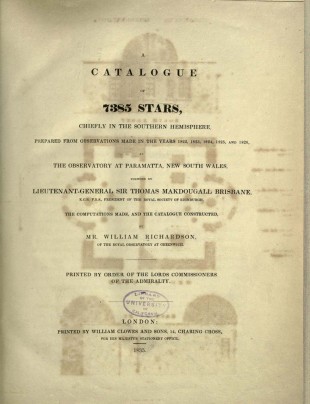

When in 1825, John Pond increased his staff to six by taking on two computers (later described as ‘extra assistants’) the new individuals came at Richardson’s recommendation – Thomas Ellis from York and his brother-in-law, William Rogerson, who like Richardson, came from Pocklington. Their arrival meant that for the next twenty years, half the professional staff working for the Astronomer Royal were Yorkshire men. In 1830, Richardson was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomcial Society for his investigation into the Constant of Aberration (the Medal was awarded to Airy in 1833 and 1846). When in 1830, the East India Company needed a new Director for its Observatory in Madras, the post was offered to Richardson, who declined it on medical grounds. It was then offered to Thomas Glanville Taylor who accepted. Richardson was also responsible for computing the data for A catalogue of 7385 stars: chiefly in the southern hemisphere, prepared from observations made ... at the observatory at Paramatta, New South Wales ... which was published for the Admiralty in 1835.Very little is known about Richardson before his arrival at Greenwich. In his article The Greenwich assistants during 250 years, which was published in 1925, Henry Hollis states that Richardson had been a blacksmith, but provides no evidence to support his assertion. Writing on his website Pocklington History, Andrew Sefton records that Richardson was one of a number of local amateur scientists who used to meet in Pocklington and had an interest in astronomy. These included the future telescope maker Thomas Cooke who came from the village of Allerthorpe (less than two miles away), William Watson of Seaton Ross (mapmaker and sundial maker), John Smith of Bielby (sundial maker and amateur astronomer) and William Rogerson.

On 29 August 1821, Richardson married Ann Rogerson, sister of William Rogerson, at St Andrew’s Holborn, London, (The Times, 7 Feb 1846 p.7 / parish register). Baptised in Scarborough, Yorkshire, Ann was roughly two years younger and had received a legacy of £50 on the death of her grandfather who, like her father and brother, was also called William Rogerson.

Other evidence of Richardson’s earlier life comes from James South, the first President of the Royal Astronomical Society. During his Presidential Address in 1830, while presenting Richardson with the Society's Gold medal, he alluded to the fact that before joining the staff of the Royal Observatory in August 1822, Richardson had spent time working for him at his private observatory in Blackman Street, Borough, London. In his address, South also described Richardson as Pond’s right hand man and referred to ‘the miserable pittance’ paid to him by the Government as being insufficient to maintain his family.

Housing paid for by the Admiralty

Richardson was appointed on an annual salary of £100 plus £10 for every three years service plus allowances. Prior to his arrival, the Observatory assistants had always been accommodated at the Observatory itself. With the increase in staff numbers, plans were developed to build extra accommodation in Greenwich Park. At that time however, new homes were being built in the area, and as a short term measure, the Admiralty decided instead to pay for suitable accommodation, along with the bills for coal and candles. Richardson, together with the Second Assistant John Henry Belville, took up accommodation at 16 Park Row. The arrangement proved rather convenient and as a result, all plans for erecting new accommodation for the Observatory were abandoned. The 1870 Street Directory lists two houses in Park Row with the number 16 – one to the north of Trafalgar Road and the other to the South. An article in volume 14 of the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society states that Belville’s house was about 180 yards from the river, suggesting he lived in the number 16 to the north of Trafalgar Road in what is now a car park.

In about 1830, Richardson moved to a house in the road now known as Circus Street. In the 1830 rate book, it was listed with other properties in Gang Lane. By the following year, Gang Lane had been renamed Royal Hill and the road where Richardson lived had been given the name Royal Circus Street, later shortened to Circus Street. When he moved in, there were only seven houses, all at the Royal Hill end. He remained there until about 1840 when he moved round the corner to a house that he had bought in Royal Hill. In January 1836, an independent valuation put the unfurnished rent of Richardson’s then house in Royal Circus at £36 and the associated taxes at £8.19s making a total of £44.19s plus up to £5 more if furnished (RGO6/72/19). The amount actually paid to Richardson in 1835 was £51.10s plus £20 for coal and candles, making a total of £71.10s (RGO6/72/223). His salary at that point was £140 a year.

Richardson the pendulum maker

In 1829, John Wrottesley, a founding member of the Royal Astronomical Society, began the construction of an observatory at his house in Montpelier Row in Blackheath. He appears to have been on good terms with the staff of the Royal Observatory (which was located less than a mile to the north) as his published catalogue of stars tells us that the staff of the Royal Observatory helped him determine the longitude of his observatory by making simultaneous observations of signal rockets and that William Richardson constructed the mercurial (compensated) pendulum of his transit clock (by Hardy), which was installed in December 1829. Richardson made a similar pendulum that was fitted to the Royal Observatory clock now known as Graham 3. Signed: RICHARDSON Royal Observatory, but undated, it was still in use at Herstmonceux in 1975 (Howse 1975). Now in the care of the National Maritime Museum, a photo of it can be seen here.

Pond’s assesment of Richardson’s abilities

As he was preparing to leave the Observatory in 1835, Pond prepared a document for his successor giving an assessment of each of his assistants. Of the six assistants, Richardson was the one of whom he spoke the most highly:

‘Mr. Richardson was recommended as assistant by the late Mr. Troughton – his qualifications when first he came here, were a knowledge of Elementary Mathematics – He is a first rate observer with the Circle, and he keeps the Circle computations in a very masterly manner … He is a very able clear headed man and rather above his work and salary – Accordingly he has been allowed to undertake computation for others; for instance those required for the catalogue of Sir Thos Brisbane – and some for the astronomical society by these means he has improved his salary – He gave instructions to the assistant employed by Mr. Airy at Cambridge [Glaisher] to fit him for that situation. … .’ (RGO6/72/223)

Richardson’s responsibilities at the Observatory were listed as observing with the Jones Circle and computing the observations of both that and the Troughton Circle. How much he was paid for his external duties is unclear. His estimate however for completing the Paramatta Catalogue was £1020, which included an unspecified amount for him to employ the services of Rogerson and Ellis to check some of his work (RGO14/48/231).

Changes under Airy

By the time Airy came to replace Pond as Astronomer Royal in 1835, for various reasons, standards at the Observatory had declined. Airy wanted rid of both the First Assistant, Thomas Taylor and also of Richardson. This was despite the fact that Richardson had been awarded the Royal Astronomical Society’s Gold medal and despite the fact that Airy had acted upon Richardson’s recommendation and employed James Glaisher at the Cambridge University Observatory in 1833. The Admiralty allowed Airy to get rid of Taylor, but not Richardson. Simms resigned soon after. Deliberately or otherwise, Richardson was then made to suffer financially. In 1836, Airy got permission to reform the allowance system. Richardson and John Henry (Belville) were left out of pocket, receiving a total allowance of just £60 each for rent, coal and candles. Airy also blocked (probably on orders from the Admiralty), the triennial pay rises to which these two individuals were entitled. This decision was eventually reversed, but not until 1843.

Under Airy, Richardson’s work, like those of a number of his colleagues was largely restricted to making observations with the Mural Circles, the Zenith Sector and the Equatorials and then reducing them.

Dismissed from the Royal Observatory

At the end of 1845, Richardson was dismissed from his post. This came about because of information passed to Airy about Richardson’s personal life. After interviewing him on Monday 27 October, Airy recorded in his journal: ‘Investigated a very serious charge of incest against W. Richardson, and suspended him from his office.’ Three days later, he was dismissed, by order of the Admiralty (RGO6/24/103).

The matter might have rested there as, at the time, incest was not a criminal offence in England and Wales (it only became so in 1908). The result of the liaison was a son which was born to Ann Maria, his daughter, on 17 September 1845. Richardson’s real undoing was that the child had died 10 days later and been secretly buried by him in his garden. That it had been so buried was only discovered because, about three months later, Richardson employed a workman to dig him a cesspool. The coffin was uncovered during digging on 22 January 1846. Initially, there was concern over the fact that neither the birth nor the death of the child had been registered. As a result, Richardson was arrested in Pocklington at the end of January 1846 and charged with concealing the birth and death of a child.

The Morden Arms where the inquest took place. In the 1890s, it was the home of David Edney one of the Observatory's longest serving members of staff. Photographed 2016

In the end, both Richardson and his daughter were acquitted as there was no concrete evidence that he had ever purchased arsenic and because it could not be proved that the positive test for arsenic was not a result of contamination in the laboratory.

After the trial Richardson returned to Pocklington, where he remained until he died. According to the report of the trial published in the Kentish Mercury (see below), Richardson’s daughter, Ann Maria, remained in the prison that night before being ‘conveyed to some refuge, there to remain until she had given birth to another child of which she is again pregnant by her filthy incestuous parent’.

Richardson’s last home in Pocklington, Paramatta Villa, is presumed to have been given that name by him as a reminder of his glory days as an astronomer under Pond.

Richardson’s family

When Airy became Astronomer Royal in 1835, Richardson had six surviving children. By the time of his trial, he had nine. The names and dates of birth of his children by his wife Ann are as follows.

Date of Birth |

Name |

||

| 1824, Jan 5 | Ann Maria | ||

| 1825, Mar 21 | Frederick William (died the same year and buried 1825, Dec 8) |

||

| 1827, Apr 30 | Frederick William |

||

| 1828, Oct 4 | Amelia |

||

| 1830, Mar 2 | Julia | ||

| 1832, Sep 28 |

Lavinia | ||

| 1834, Sep 28 |

Eliza | ||

| 1836, Jan 24 | Louisa | ||

| 1839, Q2 | Lucy Corinna | ||

| 1842, Q4 | William Charles Augustus |

At the time of the 1841 census, Richardson was in Greenwich with his two daughters Ann Maria and Amelia, but his wife was in a house in Chapmangate, Pocklington (where she was listed as head of household) with their other daughters Julia, Lavinia, Eliza, Louisa and Lucy.

At the time of the trial, Richardson was still living in house in Greenwich, but his wife was reported as living in Friendly Place in nearby Deptford with at least some of his daughters (The Weekly Chronicle, 1 February 1846 p.5).

On the night of the 1851 census, Richardson was in his house in Pocklington together with three of his children, Julia, Lucy and William. His wife was elsewhere.

On the other hand, at the time of the 1861 census, Richardson and his wife appear to be living together in Pocklington together with three of their children: Ann Maria, Eliza and William together with their granddaughter, Louisa (aged 4). Ten years later at the time of the 1871 census, the family were living in Paramatta Villa, the household consisting of Richardson and his wife together with their two daughters Ann Maria and Louisa and their grandchildren Louisa (aged 14) and Henry (aged 8).

Richardson’s daughter Ann Maria is thought to have given birth to at least three children and if the account in the Kentish Mercury is to be believed at least four:

Date of Birth |

Name |

Father |

|

| 1845, Sep 17 |

Theodore Horatio Richardson (d.1845, Sep 27) |

Her father, William Richardson |

|

| 1846 |

? |

Said by the Kentish Mercury to be pregnant by her father (see above) |

|

| 1856, Nov 8 |

Louisa Richardson |

Not recorded |

|

| 1862, Oct 18 | Henry Richardson | Not recorded |

Louisa was born at Fitzroy Terrace Gate Fulford and Henry at home in ‘Paramata House’ in Pocklington. Since the name of the father was not recorded when their births were registered, some have speculated that their father was in fact William Richardson. If that was the case, just what were the domestic arrangements of the Richardsons between 1840 and the time of William Richardson’s death in 1872?

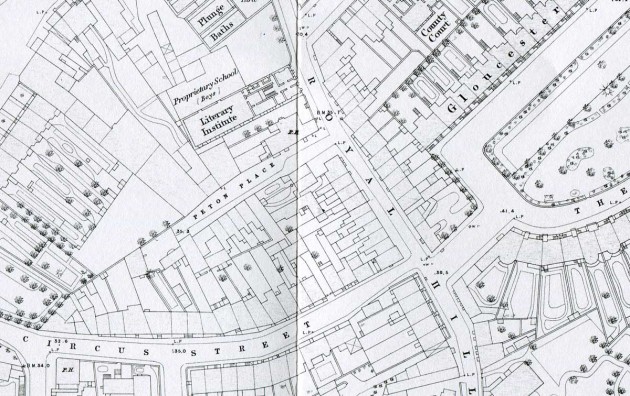

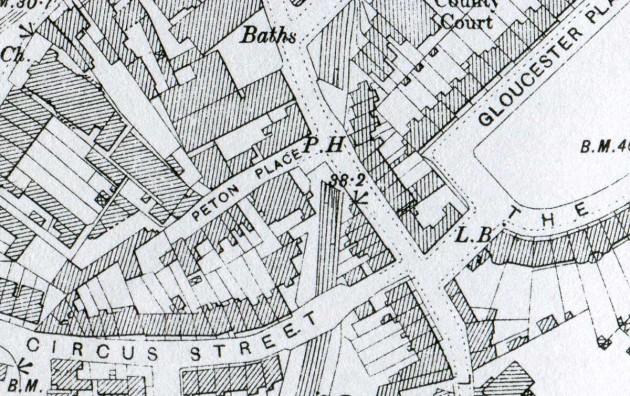

Property holdings in Greenwich

A study of the Greenwich Rate books shows that by 1841 Richardson was the owner of two neighbouring properties in Royal Hill, just south of the junction with Peyton Place. The tithe map of 1838 (below) shows a workshop and a run of ten houses on the west side of Royal Hill between Peyton Place and Royal Circus Street (now known as Circus Street). Those owned by Richardson have been marked (1) and (2) on the extract below. In 1841, Richardson was living in (1) and letting out (2). By 1845, he had increased his property holding with the acquisition of two adjacent properties. One was a larger house in Peyton Place (4), which was opposite the Globe Public House, and where Richardson was living in 1845. The other (3) was on the corner of Royal Hill and Peyton Place and had an attached workshop. In 1845, the four properties (1, 2, 3, 4) had rateable values of £12, £12, £15 and £20 and were estimated to have gross rental values of £15, £15, £18 and £24. By 1846, all four properties had been sold and Richardson was living back in Pocklington.

It is worth noting that the size and rateable value of the house in which Richardson was residing in 1841 was significantly lower than that of his previous house in Royal Circus Street. Why then, with a growing family, did he make the move? What was the reason for buying rather than continuing to rent, and was the downsizing the trigger for his marital problems? We can, it seems, only speculate.

Detail from the 1838 Tithe Map by FW Simms (a former Observatory assistant). See above for details of Richardson's property holdings (1, 2, 3 & 4). Reproduced by permission of the Greenwich Heritage Centre (see below)

In 1867, Richardson's three former properties on Royal Hill still existed much as before. The house in Peyton Place (where his child's body was found) appears to have been either demolished or altered to form a pair of semi detached houses. Detail from the1867 Ordnance Survey map (36 inches to the mile)

Richardson's houses on Royal Hill were demolished in the 1880s to make way for a new branch line that ran in a newly dug cutting from Lewisham to the centre of Greenwich. Detail from the 1894 Ordnance Survey map (1:2500)

The site of Richardson's houses in March 2017. After the railway ceased operating in 1917, the cutting was infilled. Until 2014, the site was in use as a car park by the Police, whose Station (now closed) was to the left of where the photograph was taken

Property Holdings in Pocklington

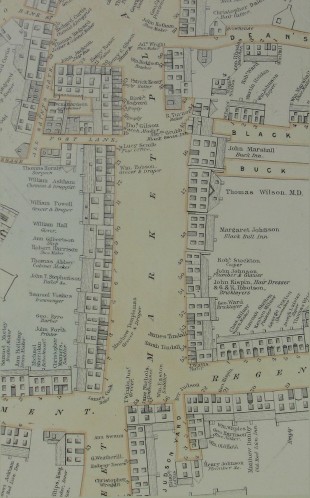

Part of William Watson's 1855 plan of Pocklington. Richardson's property holdings are shown top left and are bounded by Post Lane, All Saint's Gate (both now renamed) and Market Place and has been reproduced from a public information panel outside Oak House (now Pocklington Arts Centre). Images of these properties as they appeared in 2017 are reproduced below beneath the two images of Sherbutt House

At the time of his death, Richardson owned some eight or nine properties in and around the Market Place, including the Star Inn and Brew-house. His residence at the time of his death (Paramatta Villa) is not mentioned in his will, suggesting that it was either rented or was held in the name of his wife.

A study of the census records for the years 1861, 1871 and 1881 together with maps and other evidence from around that period, suggests that Paramatta Villa was built between 1861 and 1871. When put up for sale in 1873 it was described in an advert in the 22 March edition of The York Herald (p.3), as being freehold and consisting of a ‘Detached VILLA RESIDENCE … with the Yard, Gardens, Coach-house, Stable, Granary, Wash-house, and other Outbuildings and Appurtenances thereto’ with ‘a Close of LAND adjoining in the occupation or Mr. Robert Smith’, the whole being a little over two acres in extent. After it had been sold, Paramatta Villa was given the name Sherbutt House and put to use as an educational establishment by Charles Nichol(l)s. The wish of its new owner to change the name is not surprising, for although the name Paramatta (more typically spelt Parramatta) had positive connotations for Richardson, it was also a name associated with convicts! Located on Yapham Road, close to the junction with Garths End, Sherbutt House still exists, but in modified form as a residential care home.

Sherbutt House School in 1876. With kind permission of the Pocklington & District Local History Group

Some of Richardson's former property in the centre of Pocklington in 2017. The former All Saint's Passage is on the left and the former Post Lane on the right. In 1855, Richardson lived in the house (now much altered) to the right of the woman with the bag on her back

Richardson's properties viewed from Market Place during the Tuesday Market in February 2017. The rebuilt former Star Inn is the red building in the centre. To its right is the former All Saint's Passage

More of Richardson's properties in February 2017. Of the five properties that made up this terrace in 1844, Richardson owned all except the one that now has the two Velux roof lights

Last Will and Testament

ON the twenty ninth day of July 1872, the Will of William Richardson late of Pocklington in the County of York, Gentleman, deceased who died on the twenty third day of March 1872 at Pocklington aforesaid was proved in the District Registry attached to Her Majesty’s Court of Probate at York by the Oath of Ann Maria Richardson of Pocklington aforesaid, Spinster, the Daughter of the said deceased, the sole Executrix therein named, she having been first sworn duly to administer.

Effects under £100. No Leaseholds

Extracted by R B Bell, Solicitor, Pocklington

This is the last Will and Testament of me William Richardson of Pocklington in the county of York Gentleman I give and devise all that my dwelling house and shop situate in the Market Place in Pocklington aforesaid now in the occupation of Henry Foster And also all that my dwelling house and shop situate in the Market Place in Pocklington aforesaid now in the occupation of Henry Clarke Gilson And also all that my dwelling house and shop situate in the Market Place in Pocklington aforesaid now in the occupation of George Nelson being that part of the premises now in the occupation of the said George Nelson in respect of which he first became my tenant with the privileges and appurtenances to the above devised hereditaments respectively belonging unto my daughter Ann Maria Richardson her heirs and assigns forever I give and devise All that my dwelling house and shop situate in the Market Place in Pocklington aforesaid now in the occupation of Thomas Gilson And also all that my dwelling house and shop situate in the Market Place in Pocklington aforesaid now in the occupation of John Dewsberry Tinson (?) with the privileges and appurtenances to the same respectively belonging unto my daughter Julia Noble her heirs and assigns forever I give and devise All that my dwelling house and shop situate in the Market Place in Pocklington aforesaid now in the occupation of Miss Thirby (?) And also all that my dwelling house and shop situate in the Market Place in Pocklington aforesaid now in the occupation of the said George Nelson being that part of the premises now in the occupation of the said George Nelson which he last became my tenant to with the privileges and appurtenances to the same respectively belonging unto my daughter Louisa Richardson her heirs and assigns forever I give and devise all that my dwelling house now used as a Public house situate in the Market Place in Pocklington aforesaid and known by the name of the Star Inn with the brewhouse yard stables chambers and other buildings thereunto belonging and occupied therewith and now in the occupation of John Jackson And also all that tenement or dwelling house adjoining or near to the said public house and now in the occupation of John Clarkson with the privileges and appurtenances to the same respectively belonging unto my Son William Richardson his heirs and assigns forever Subject nevertheless to and I do hereby charge and make chargeable the whole of the hereditaments hereinbefore given and devised to my said daughters Ann Maria Richardson Julia Noble and Louisa Richardson and my said son William Richardson with the payment of the mortgage debt with which the same is now charged and liable to in the proportions and according to the annual value of the respective devises and which for that purpose shall be as follows that is to say the hereditaments devised to my said daughter Ann Maria Richardson as being of the annual value of forty seven pounds the hereditaments devised to my said daughter Julia Noble as being of the annual value of thirty eight pounds the hereditaments devised to my said daughter Louisa Richardson as being of the annual value of twenty three pounds and the hereditaments devised to my said son William Richardson as being of the annual value of forty five pounds I bequeath all my household furniture plate linen china wearing apparel books pictures paints (?) liquors (?) fuel and housekeeping stores and effects to my dear wife Ann Richardson absolutely I give devise and bequeath All the residue of my real and personal estate to my said daughter Ann Maria Richardson my said daughter Julia Noble my said daughter Louisa Richardson and my said son William Richardson their respective heirs executors administrators and assigns as tenants in common and not as joint tenants Subject nevertheless to and I do hereby charge the said residue of my real and personal estate with the payment of all my just debts (except the mortgage debt now existing upon my property situate in the Market Place in Pocklington aforesaid and which I have hereinbefore directed to be paid out of the property charged therewith) funeral and testamentary expenses and the expense of registering this my Will I devise all real estates vested in me as trustee or mortgagee to my said daughter Ann Maria Richardson Subject to the trusts and equities affecting the same respectively I appoint my said daughter Ann Maria Richardson sole Executrix of this my last Will and Testament I revoke all former Wills and declare this writing to be may last Will and Testament In Witness whereof I the said William Richardson the testator have hereunder set my hand this twenty ninth day of February in the year of our Lord one thousand and eight hundred and seventy two

William Richardson

Signed by the above mentioned William Richardson the testator as and for his last Will and Testament in the presence of us present at the same time who at his request in his presence and in the presence of each other have hereunto subscribed our Names as Witnesses

R B Bell

Thomas Wilson, M.D.

Proved at York the twenty ninth day of July 1872 by the oath of Ann Maria Richardson Spinster the daughter the sole Executrix to whom administration was granted

The Testator William Richardson was late of Pocklington in the county of York, Gentleman, and died on the twenty third day of March 1872 at Pocklington aforesaid.

Extracted by R B Bell Sol’r Pocklington

Under £100 No leaseholds

This is a true copy

Further reading

The Times (January – May 1846). Court reports relating to the murder

| Police / Coroner’s Court | January 26 (p.7). February 3 (p.5). February 6 (p.8). February 7 (p.7). February 13 (p.8). February 16 (p.3) | |

| Central Criminal Court | May 14 (p.8) |

Kentish Mercury, 16 May 1846, trial report and comment

Richardson, William (b. 1796/7, d. after 1846). Roger Hutchins, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004–15. This account contains factual errors relating to the nature of his appointment and salary.

The Star Inn. Pocklington History website

Sir Thomas Brisbane – a man of scientific method. Carol Liston Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, vol. 145, nos. 445 & 446, pp. 136–145. (2012)

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to the Greenwich Heritage Centre for permission to reproduce part of the 1838 Tithe Map. The Centre also holds the Greenwich Rate Books.

Thanks also to Andrew Sefton and to Andrew Wells who provided the transcription of Richardson’s Will and other assistance.

© 2014 – 2025 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan