…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

People: Thomas Taylor

This page is currently in the process of being updated

| Name | Taylor, Thomas |

||

| Place of work | Greenwich | ||

| Employment dates |

1 Jul 1807 – Sep 1835 |

||

| Posts | 1807 |

Assistant |

|

| 1811 |

First Assistant (by default) |

||

| Born | 1772 |

||

| Died | 1843, Jan 23 |

||

| Family connections | Father of Thomas Glanville Taylor, Assistant (1822–1830) | ||

| Father of Henry Taylor, the discredited editor of the Groombridge Catalogue & husband of the sister of the wife of John Pond the Astronomer Royal |

|||

| Known addresses | 1807–1835 | Royal Observatory, Greenwich |

|

| 1835–1843 | 17 Melbury Terrace, Marylebone |

||

| 1838 & 1843 | The Kensington House Asylum (Finch’s Madhouse} | ||

Following the resignation in 1807 of Thomas Ferminger as his Assistant, the fifth Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, appointed Thomas Taylor, to replace him. Taylor served under both Maskelyne and his successor John Pond.

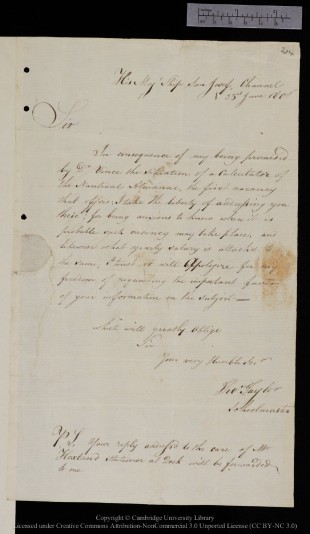

Taylor's letter to Maskelyne. It is dated 23 June 1806. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

Taylor’s duties and Pond’s assesment of him

Until Pond’s arrival as Astronomer Royal in 1811, only one assistant was normally employed at the Observatory. By 1825, Pond had six assistants at his command. As the longest serving, Taylor became by default, the First or Chief Assistant. In a note written for his successor Airy in 1835, Pond described him as having been a most trusted servant, but went on to say ‘He may now be considered as quite superannuated; his sight is imperfect; he has grown petulant and has latterly taken to drinking’. His duties were described as observing with the Transit, superintending all the computations and corresponding with the captains of ships respecting chronometers. Like the other assistants, Taylor also spent time rating the chronometers and operating the Time Ball, which at that time, was dropped by hand (RGO6/72/223&226).

Pond’s Discussions with the Admiralty and Visitors on increasing the number of Assistants

This section is a much abridged version of a similar section written in an article about John Pond.

What is striking throughout the whole saga surrounding the appointment of additional Assistants, is the abdication of responsibility and a failure of leadership on the part of Pond. Seemingly not in a position to negotiate directly with the Admiralty who funded the Observatory, (which is broadly what seems to have happened under his successor), Pond’s negotiations all took place indirectly though the President and Council of the Royal Society which included, one or other of the two secretaries of the Admiralty – the very same people, who when wearing their Admiralty hat, were largely responsible for deciding the outcome. The end result was that the waters became muddied, and nobody took ownership of control of the process in order to see it to a timely conclusion. In these circumstances, it is perhaps no surprise that the negotiations dragged on for four years and were carried on without proper consideration as to how they might be put into effect.

In 1823, a well-meant, but injudicious attempt to give Pond assistants of a superior class with a university education and great mathematical attainment at a higher salary was not resisted by him at the time, even though he did not want such assistants. The type of assistant he really wanted was eventually revealed in a letter that he wrote three years later to his friend William Hyde Wollaston (RS MS371/49). It began as follows:

‘You have desired me to state to you confidentially, in case the question respecting the assistants, should again be considered by the council, what my real and undisguised opinion is, as to the class of persons from which for the interest of the observatory it is expedient to choose them.

I am and always have been extremely unwilling to offer or appear to offer resistance to what seemed to me to be the marked inclination of some of the members of the board of Admiralty and of the council, and actuated by this feeling I may have been less explicit at the council in expressing my real sentiments on this subject than I ought to have been – what that opinion is however and always has been I will now state’.

After re-explaining that the new methods of observing with two mural circles generated a large number of observations that needed to be reduced, Pond went on to say:

‘... I want indefatigable hard working and above all obedient drudges (for so I must call them, though they are drudges of a superior order) men who will be contented to pass half their day in using their hands and eyes in the mechanical act of observing, and the remainder of it in the dull process of calculation.’

He then went on to explain that these were not the characteristics he would expect to find 'in the highly educated class of our universities' and that he would feel ‘some compunction’, in asking them to undertake such mundane work. Nor he said, was there a need for ‘mathematical talent of a superior order’.

Pond then raised another important objection:

‘It does not appear to me conducive to the good feeling which I wish to see maintained among them to have two classes of servants performing the same duties, but rewarded in a very unequal manner.’

His letter continued:

‘In spite of these objections which I feel to the new plan I beg you to understand that should that plan be finally decided on, I am now as I always have been ready cheerfully to acquiesce on it and carry it into execution.’

To cut a very long story short, in 1824, it was proposed and agreed that Taylor ‘be allowed to retire with a suitable pension, and that a new assistant be appointed in his place of the superior class’. This did not happen, and in the end, it was agreed that Taylor should be retained in his present position.

What Taylor knew of the discussions and proposals is unclear, but it seems highly likely that he was aware of them. To put oneself in his shoes; how might we feel if our job was suddenly advertised, or if we were offered early retirement only to have the offer effectively withdrawn?

And who was to blame for the way things progressed? Was it Pond with ‘his dislike to every thing like contention’? He could have fought his corner openly but chose instead to fight it by stealth. Was it the Council of the Royal Society, who arguably overstepped their role as Visitors? Was it the Admiralty and the Royal Society together for bulldozing the Astronomer Royal rather than properly engage him in discussion? Or should the blame instead be placed on the shoulders of the former President of the Royal Society, the deceased Joseph Banks and the system of patronage that he promoted? The saga is most often remembered for Pond’s 1826 reference to ‘obedient drudges’. Perhaps instead, it should be remembered for both Pond’s abdication of responsibility in order to avoid conflict and as an unfortunate legacy of the failed Banksian regime. In the end, no assistants of a superior class were appointed while Pond remained Astronomer Royal. In addition, of the six assistants Pond appointed, all, with the possible exception of Simms (who was appointed in 1830), were initially taken on without proper authorisation from the Admiralty.

The Ponds and the Taylors – one big happy family?

This section is a much abridged version of a similar section written in an article about John Pond.

On the 16 April 1807, the 39 year old future Astronomer Royal John Pond married 17 year old Anne Gordon Bradley (1789–1871). As far as can be ascertained the couple did not have any children.

In March 1802, Thomas Taylor (1772–1843), married Susanna Glanville (1774?–1820) in Devon. Taylor’s will shows that he had four children who survived him. They were Susanna Taylor (1803– ) who married William Richards; Thomas Glanville Taylor (1804–1848); Henry Taylor (1810–1874) and Harriett Taylor (1813–1869) who appears to have been unmarried at the time of her father’s death.

In 1822, Thomas Glanville Taylor was taken on by Pond as one of two new assistants. He was appointed Director of the East India Company’s Observatory in Madras in 1830 and elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1842.

Born in 1810/11, six years after his brother Thomas, Henry Taylor is recorded as having gone to the University of Oxford to study. His entry in volume 4 of Alumni Oxonienses (which is said to have been compiled from the University’s matriculation register) records that he matriculated at All Soul’s College at the age of 17 on 21 April 1828. Other sources have him supposedly attending St. Mary Hall (Essex Standard, 2 December 1839), and Magdalen Hall. He is said to have graduated with the degree of Bachelor of Civil Law (B.C.L.) in 1832.At about the age of 21, Henry got married, the wedding taking place at St James’s Piccadilly on 28 July 1832. Intriguingly, his bride, who was ten years his senior, was Mary Ayrton Ellen Bradley, sister of the wife of John Pond – in other words, John Pond’s sister-in-law was also the daughter-in-law of Thomas Taylor. Taylor and Pond both retired in 1835. By the time of Pond’s death in 1836, Henry must have taken Holy Orders as he swore (as the Reverend Henry Taylor) the truth of an affidavit stating that Pond’s will appeared genuine.

Pond’s death left his widow Anne in much reduced circumstances. It appears that by 1837 if not before, she had moved in with Henry and Mary Taylor and that the three of them subsequently moved in with Thomas Taylor (and Harriett?) at 17 Melbury Terrace, Dorset Square, Marylebone. Court records held by the National Archive (HO 17/47/144) suggest that he (Thomas) had been living there since 1835 when he retired.

Henry became curate of Christ Church Marylebone at the start of 1839. In the summer of 1839, he also became one of the domestic chaplains of the Earl of Powis, a position that he held throughout the rest of his life. This particular appointment (which was announced in July/August) probably came about because the Earls of Powis were descendents of Margaret Maskelyne, wife of Clive of India and crucially, sister of Nevil Maskelyne, his father’s first employer at Greenwich. The Gentleman’s Magazine records that in December 1839, he was appointed incumbent of All Saints’ Church, Stepney.

In 1840, Thomas Glanville Taylor was back in England on leave from Madras. The following year, Henry Taylor was appointed Chaplain to the East India Company. When Thomas Glanville Taylor returned to India at the end of 1841, Henry travelled with him. Henry remained in the service of the East India Company and later the Colonial Office (after the reorganisation of 1858) until 1860. It is not presently known if Anne Pond or his wife and children accompanied Henry Taylor to Madras.

The 1871 census shows Henry and Mary Taylor together with Anne Pond and two servants as the sole occupants of South Lodge in Broadstairs. The probate records show that both Anne Pond and Henry Taylor died at South Lodge; Anne on 17 April 1871 and Henry three years later on 26 June 1874. Mary Taylor died in the same parish on 23 February 1878.

The question arises as to how it was that the Ponds and the Taylors became so close and what bearing this might have had on the working relationship between them? When Thomas Taylor was taken on by Maskelyne in 1807, he was already married with two Children (Susanna and Thomas G). Henry was born a few months before Pond arrived at the Observatory in 1811 as Astronomer Royal. At that time, Thomas Taylor was the only Assistant. Although accommodation was provided for him at the Observatory, it is not known if the rest of the family resided there. Given the hours he seems to have been required to work, it seems probable that they did, a view supported in a note about the assistants that Pond wrote for Airy in 1835 that states that ‘his [Taylor’s] eldest son was brought up at the Observatory and is now astronomer at Calcutta – to the East India Company’ (RGO6/72/233). The new apartment rooms completed in 1815 seem to have been initially shared between the First and Second Assistants (RGO6/44/9), however a plan from 1831, indicates that by then, one of the rooms had been divided and that the whole suite of about 400 square feet was in use by Taylor (RGO6/45).

Taylor’s wife Susanna died in 1820, leaving him with four children between the age of seven and seventeen to bring up on his own. It seems highly likely that from an early stage that the Ponds took an interest in the welfare of the children and also their education. How else would Henry have got to meet Mary Bradley let alone to marry her?

Although Henry Taylor was never employed as a member of the Observatory staff, he made a significant number of the published observations with the transit instrument in 1830 and 1831 and was conversant with the process of reducing the observations for publication as both he and his brother were involved in the production of Groombridge's Catalogue of Circumpolar Stars, the production of which was being funded by the Board of Longitude. Of the two brothers, it was initially only Thomas Glanville Taylor who was involved. After his departure for India, it became necessary to appoint a new superintendant of the computations;

‘and Pond, apparently in his official character as Astronomer Royal, nominated Mr. Henry Taylor, [who was then aged just 20], brother of Mr. T.G. Taylor above mentioned. The calculations it appears, were first put into his hands in about June, 1830 [around the time he made his first transit observation]. Computers were employed by Mr. H. Taylor; the reductions were completed; the Catalogue in every respect prepared for press; and, after the necessary sanction from the Board of Admiralty, the Catalogue and Introduction were completely printed [in 1832?] at the expense of the Government.’

To cut a long story short, before the volume was actually published, aspects of the work were found to be erroneous. According to Airy, the errors were of such a nature that no system of cancelling or errata could remove them and it was decided that the work ought to be suppressed. Following a significant amount of extra work by Airy and others (Sheepshanks in particular), the volume as edited by Airy was eventually published in 1838. An account of the Taylors’ involvement in its production (from which the above quote is taken) was given in the Preface to the Catalogue. It is worth spending a few minutes reading it. The account given in the History of the Royal Astronomical Society, 1820–1920 differs slightly, and is reproduced below:

‘After 1830 June this work was done by a Mr. Henry Taylor, a brother of the well-known astronomer at Madras, and a son of Pond’s First Assistant. He felt aggrieved at the account given of the work in the obituary notice of Groombridge in the Annual Report of 1833 (written by Sheepshanks), though his name was not mentioned in it. His complaint, that statements in the obituary were “totally inaccurate and essentially wrong,” was investigated by a Committee, who reported to the Council that his charge was “ frivolous and unfounded “ ; which report the Council adopted. Upon which Mr. Taylor, deeply offended, resigned his fellowship of the Society. But he would have been much wiser if he had let Sheepshanks alone. For that indefatigable worker, who was now put on his mettle, at once proceeded to make a thorough examination of the reductions and of the printed catalogue, which only wanted the introduction (which was in type) to be printed off in order to be published. This examination led him to find so many errors, that he pronounced the catalogue unfit for publication. At the request of the Admiralty, the matter was next investigated by Airy and Baily, who decided that the errors were of such a nature that no system of cancelling or list of errata could remove them; so that the catalogue ought to be suppressed. Eventually a new catalogue was prepared under the superintendence of Airy, the main bulk of the reductions being found to have been well done; and this was published in 1838.’

When Airy arrived at Greenwich as the new Astronomer Royal, he seems to have found no formal records relating to the structural changes that happened during Pond’s tenure (funding, reconstituted Board of Visitors, minutes of the Visitors etc.). Nor could he find any record of how the site and instruments had evolved since Flamsteed's time. Time being of the essence and Pond himself being dead, Airy wrote to Anne Pond in 1837, who roped in Maskelyne's daughter Margaret and Thomas Taylor to help fill in the details. As well as getting information via Anne Pond, Airy also had sight of a private journal kept by John Belville for the years 1811–1825, from which he made copious notes. The undated notes made from the journal (but not the journal itself) are preserved in the Observatory archives (RGO6/1). For reasons unknown, in March 1847, Belville gave Airy sight of a bundle of private letters Pond had written to him from Hastings whilst on sick leave and recuperating. A page and a half of notes consisting of 41 lines of text and about 300-400 words that Airy made from them are also preserved in the Observatory archives (RGO6/1/58) under the heading: Remarks on a bundle of letters addressed by Mr. Pond to Mr. Henry during his long absence from the Observatory in 1831. There was also an accompanying letter from Belville (RGO6/1/57).

Airy’s notes give the impression that there were eleven letters from Pond in total, the first having been written on 27 July 1831 and the last four months later on Tuesday 29 November when Pond said he hoped to be back home by the following Monday or Tuesday. Airy transcribed sections from eight of the letters. Together, they show that Pond was in a seriously bad way both physically and mentally and that at one point, he feared that he would never return to Greenwich.

In the absence of the originals letters it is not possible to tell either the original context of the copied extracts nor why Airy recorded these sections and not others. Two extracts (about 20% of the text that was copied) make reference to the Taylors. Taken at face value, they are exceedingly damning.

Letter 1. ~ 27 July 1831

‘Rely on it that whatever becomes of me you will be comfortably provided for at the Observatory with proper diligence. I have been ill used by the Taylor family, but do not notice this or pretend to know it’

Letter 2. ~ 31 July 1831

‘I hope to have no intercourse any more with the Taylor family, but do not pretend to know this. Nothing can equal the ingratitude of their conduct.’

But what was it that the Taylor family was supposed to have done to bring on this outpouring at this time? The answer is not at all clear. And what did Pond mean by ‘but do not notice this or pretend to know it’ and ‘but do not pretend to know this’. Was it that he, Pond, was pretending not to know it, or was it an instruction to Belville not to share with the Taylors his (Pond’s) thoughts on them? And if, as seems more likely, it was the second of these, it suggests a somewhat divided workforce.

At the time when Pond was writing, Thomas Glanville Taylor was off the scene having departed for Madras more that a year before, and the Groombridge / Henry Taylor incident was still more than a year away as was Henry’s marriage to Mary Bradley.

In January 1831 the newly constituted Board of Visitors met for the first time. At the visitation in June, Pond made a lengthy statement in which he said ‘... only one assistant [presumably Taylor] is lodged at the observatory, and that only on sufferance’ (ADM4/62). The reference to him residing there ‘under sufferance’ can be read in at least three different ways.

1. Taylor and Pond’s relationship had broken down.

2. After nearly 25 years of doing so, Taylor was fed up with both working and living under the watchful eye of the Astronomer Royal in the same immediate environment.

3. That the accommodation provided at the Observatory was too small and too basic especially in comparison to the off-site accommodation of the Second and Third Assistants Belville and Richardson that was being paid for by the Admiralty.

Nothing is known about how or where Pond met his future wife. Nor is anything known about their relationship. She seems to have got on well with her sister, brother-in-law and Thomas Taylor ... which does make one wonder just what it was that the Taylors had done to upset Pond so much.

Taylor’s invention of an alarm clock

Astronomical alarm clock by William Johnson, a London maker, who built several copies of the clock from Taylor's designs. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) licence courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London (see below)

Taylor’s retirement

When first sounded out about the post of Astronomer Royal in 1834, Airy indicated that he would like Taylor to be removed from his post (RGO6/1/145). In the letter dated 15 June 1835 and written in confidence to Lord Auckland (First Lord of the Admiralty) before finally accepting the post, he listed the changes he would want to make at the Observatory (RGO6/1/158). His list began as follows:

‘The first, which I consider absolutely necessary, is the removal of the present first assistant Mr. Taylor. He is a drunkard, he has lost his authority over the other assistants by having recourse to them (as I believe) for the assistance of his son Henry Taylor in a scandalous business, and he is under the accusation (printed as I have heard, in some periodical) of receiving bribes from chronometer makers.’

Whilst Pond was aware of a drink problem, the charge or receiving bribes is unsubstantiated, whilst the Henry Taylor business is a reference to the Groombridge Catalogue mentioned above.

As well as wanting rid of Taylor, Airy also wanted rid of Richardson. The Admiralty agreed to the former, but not to the latter. As a result, Taylor was pensioned off with Pond at the end of September 1835.

Confined to an Asylum

In his book The Madhouse System which was published in 1841, Richard Paternoster states (p.72) that Taylor (who was described as John Taylor, deputy-astronomer of Greenwich Observatory) had been confined to Finch’s Madhouse (The Kensington House Asylum) ‘by his son the Rev. Mr. Taylor of 17, Melbury Terrace, Dorset Square’, but since removed. Regrettably, no further details were given except that he was there in 1838 at the same time as Paternoster. Taylor must however have been readmitted to Kensington House as this is the address given by the General Register Office on a certified copy of an entry of death. It records that Taylor died of inflammation on 23 January 1843.

Last will and testament

This is the last Will and Testament of me Thomas Taylor of Melbury Terrace Dorset Square in the county of Middlesex Esquire

First I direct that all my just debts funeral and testamentary expenses may be paid as soon as conveniently can be after my decease and whereas I have lately purchased in the joint names of myself and my daughter Harriett Taylor in the books at the Bank of England the sum of three hundred and twenty two pounds stock three per centum consols now I do hereby declare that I consider this as a free gift to my said daughter and which I do for the purpose of avoiding the probate and legacy duties and I give and bequeath unto my said daughter Harriett Taylor all those my two leasehold messuages or tenements and premises with the appurtenances situate in Tranquil Vale Blackheath in the Parish of Lewisham in the county of Kent and which I hold under Mr Jackson and Mr Woodgate and all that my other leasehold messuage or tenement and premises with the appurtenances situate in Park Street Greenwich in the county of Kent aforesaid which I hold under Mr Martin to hold the said respective premises unto her my said daughter Harriett Taylor her Executors Administrators and assigns for the remainders of the respective terms which shall be to come therein at my decease for her and their own use subject to the rent and covenants in the leases under which I hold the same also I give and bequeath unto my daughter Susannah Richards wife of William Richards all that my leasehold messuage or tenement and premises with the appurtenances situate in South Street Greenwich aforesaid which I hold under the Trustees of Morden College to hold that same unto my said daughter Susannah Richards her Executors Administrators and assigns for the remainder of the term which shall be to come therein at my decease for her and their own use subject to the rent and covenants in the lease under which I hold the same also I give and bequeath unto my said daughter Susannah Richards the sum of four hundred pounds owe[d?] to me on mortgage from the late James Russell of Blackheath aforesaid secured on certain leasehold premises at Blackheath and all Interest which shall be due thereon at the time of my decease and the security for the same to hold the same unto her my said daughter Susannah Richards her executors administrators and assigns for her and their own use also I give and bequeath unto my son Thomas Glanville Taylor all that my leasehold messuage or tenement and premises with the appurtenances situate and being in the Egerton Road in the parish of Greenwich aforesaid which I hold under Mr Valentine to hold the same unto him my said son Thomas Glanvill Taylor his executors adminstrators and assigns for the remainder of the term which shall be to come therein at my decease to and for his and their own use subject to the rent and covenants in the lease under which I hold the same also I give and bequeath my duplex silver watch to the older Son of my Son Thomas Glanvill Taylor for his absolute use and all my wearing apparel to my son Henry Taylor for his absolute use and as to all the Rest Residue and Remainder of my property Estate and Effects whatsoever and wheresoever which I shall die possessed of and not hereinbefore by me disposed of I give and bequeath the same after and subject to the payment thereout of all just debts funeral and testamentary expenses unto my said two sons Thomas Glanvill Taylor and Henry Taylor and my said two daughters Harriett Taylor and Susannah Richards equally to be divided between them share and share alike their respective absolute use and I do hearby nominate constitute and appoint George Smith of Park Row Greenwich aforesaid Esquire and Robert Christopher Parker of Greenwich aforesaid Gentleman Executors of this my will and I do declare that they respectively shall be answerable only for so much of my property Estate and Effects as they respectively shall actually receive or shall come to their hands by virtue of this my will and that the one of them shall not be answerable or accountable for the other of them or for the acts deeds receipts disbursements or defaults of the other of them the joining receipts for conformity notwithstanding but each of them for his own acts deeds receipts disbursements and defaults only and that they respectively shall and may out of the monies coming to their hands by virtue hereof retain to and reimburse themselves respectively all loss costs charges damages and expenses which they may respectively be put unto in the Execution of this my will and lastly I do hereby revoke annul and make void all former Wills Codicils and Testamentary dispositions by me made and do publish and declare this only to be my last Will and Testament In Testimony whereof I the said Thomas Taylor have to this my last Will and Testament contained in two sheets of paper affixed together with my seal set my hand and seal to wit my hand to the first sheet thereof and my hand and seal to this the second and last sheet thereof this tenth day of october one thousand eight hundred and thirty nine

Thomas Taylor Signed sealed published and declared by the said Thomas Taylor the Testator as and for his last Will and Testament in the presence of us (who were both present at the same time) and who at his request in his presence and in the presence of each other have hereunto subscribed our names as witnesses attesting the same Rich. Hickman 11 Chapel St Edgware Road St Marylebone – E Hayward 11 Chapel Street

Proved at London 24th July 1843 before the worshipful John Danberry[?] Doctor of Laws and Surrogate by the oath of Robert Christopher Parker the surviving Exor. to whom Admon was granted having been first sworn duly to Administer

Transcribed from the Will of Thomas Taylor of Melbury Terrace Dorset Square, Middlesex (PROB 11/1983/157) by Andrew Wells

Notes:

1. Two variant spellings Glanville and Glanvill are used.

2. All the properties mentioned in the will are/were within a mile of the Observatory.

3. Built in about 1825, Melbury Terrace was a road immediately to the west of Dorset Square that ran along the east side of Harewood Square. Melbury Terrace and Harewood Square were swept away in the 1890s to make way for Marylebone Station. To add to the confusion, the south side of Blandford Square,which was immediately to the north of Harewood Square, was renamed Melbury Terrace at some point in the (mid?) 20th century. This road too was subsequently swept away during a later redevelopment.

Image licensing information

The 1806 letter from Taylor to Maskelyne is reproduced reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library. The image is reduced in size and are more compressed than the original. Download original image here.

The image of the Astronomical Alarm Clock is reproduced under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) licence courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Object ID: ZAA0525 and was obtained via https://www.oldashburton.co.uk/remarkable-and-interesting-people.php.

© 2014 – 2025 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan