…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

Journeyman Clocks

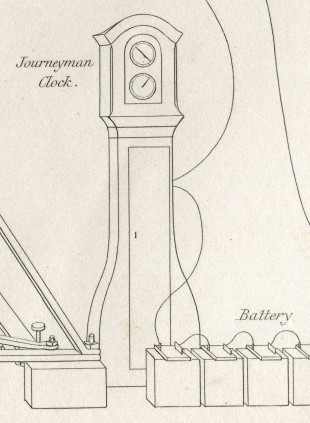

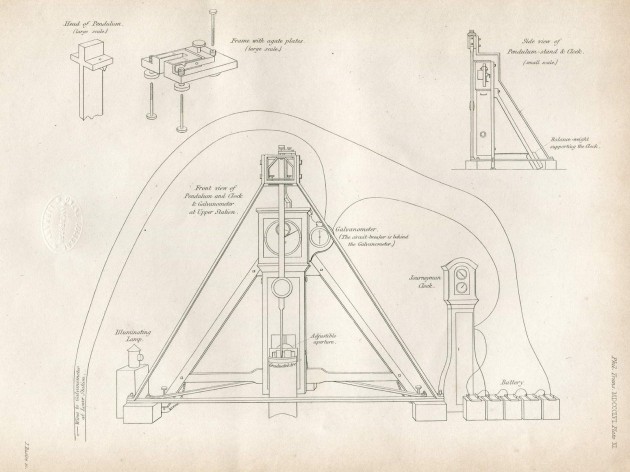

One of the Shelton journeyman clocks as adapted by the Astronomer Royal, George Airy, for use at Harton Colliery in 1854. Drawn at Greenwich by Airy with the aid of a camera lucida. Detail from plate XI accompanying Airy's Account of pendulum experiments undertaken in the Harton Colliery, for the purpose of determining the Mean Density of the Earth. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1856 146, 297-355

To understand the function of a journeyman clock, it is necessary to know something of the way that astronomers timed transits and other events. From the seventeenth until the mid nineteenth century, they used what is known as the "eye and ear" method. This was explained as follows by George Forbes in an article about the Observatory that was published in the 1872 volume of Good Words:

‘Suppose we have an upright wire in the focus of the telescope, so placed that when a star is on the meridian its image is on the wire. If a clock is made to tick loudly at our side, when we see a star advancing towards the wire we can look at the clock to see what second the hand is pointing at, say five, and then go on counting the ticks of the clock, six, seven, eight, and so on. The star is not likely to be on the wire exactly at a tick of the clock. Suppose at the twenty-second second the star has not reached the wire, and at the twenty-third it has passed. We can estimate the fraction of a second very accurately by noticing the position that the star held with respect to the wire at the twenty-second and at the twenty-third second. Having determined the second, and fraction of a second, we can look at the clock-face and see the minute and hour. This method is often employed, but five or seven wires are used, and the mean value is taken. It is called the Eye-and-Ear method, because the ear judges of the seconds, and the eye of the fractions of a second.’

The observing clocks used were of the highest quality and were known as astronomical regulators. From the beginning, those at Greenwich, like many of the ones elsewhere, contained what is known as a deadbeat escapement. This helped improve the accuracy of the clock, but had the downside, from an observer’s point of view, that the ticking noise was very quiet. This meant that in windy weather, the clock could not always be heard. It was to overcome this problem that journeymen clocks, which had much louder ticks, were sometimes used in tandem.

The design and method of use of the first Shelton jouneymans at Greenwich was described by Maskelyne in a note he inserted with the published transit observations for 27 April 1766.

In order to make sense of what he wrote it is necessary to know a little more about the way the astronomical regulators were adjusted. It was very rare for them to show the correct time. Those in different parts of the observatory would typically be showing slightly different times, as was the case on 27 April 1766. That’s because important thing about a regulator was not that it showed the correct time, but that it gained or lost time at a steady and predictable rate, so that the correct time could then be calculated with confidence by reference to the stars. To read more about this click here. Maskelyne had been having problems with the transit clock which was about to be dismounted for repair. While it was out of action he proposed instead to use the quadrant clock at the other end of the building together with a journeyman clock to time the transits. This is what he wrote:

‘Quadrant Clock 34’’ [seconds] faster than Transit Clock, at 1h 48’. Then Transit Clock was taken down to be cleaned, and to have a new Spring put to the Suspension of the Pendulum; the old one having been bent a little about the Year 1760.

In the mean Time, until the Transit Clock is set up again, the Observations are taken according to the Time of the Quadrant Clock, by means of a secondary Clock, lately set up in the Transit Room, having a loud beat which may be distinctly heard in the Quadrant Room at the same time with the Beat of the Quadrant Clock; whereby their Agreement or Disagreement is easily noted, and the Secondary Clock, by only putting forward or holding back its Pendulum, before each Observation, where necessary, is brought to agree exactly with the Quadrant Clock. This Secondary Clock, together with another of the very same make, which is put up in the Great Room, were principally designed to supply the lowness of the Beats of the Primary Clocks, standing in their respective Rooms in windy Weather. They have wooden Pendulums which beat Seconds, have only two Hands, one pointing out Minutes, the other Seconds, and strike exactly at the Beginning of every Minute. When carefully adjusted, they will keep Time exactly with the Primary Clocks for several Hours. They were made by Mr. John Shelton. There is frequent Occasion to use the Secondary Clock in the Great Room, but that in the Transit Room very seldom, nor will it be necessary except in very high Winds, such as are most usual in the Month of March.’

The two journeyman clocks had been asked for by Maskelyne in a letter, dated 28 March 1765, that was written soon after his appointment and in which he set out a list of repairs and new instruments that he regarded as being necessary (RGO6/21/85). In it, he states that Shelton had estimated their (joint) cost as being ten or twelve pounds. After various bureaucratic delays, Maskelyne was authorised to order them at the meeting of the Visitors held on 17 October 1765 (RGO6/21/99). Their exact date of arrival at the Observatory is unknown. As indicated above, one was originally located in the Transit Room and one in the Great Room (now known as the Octagon Room).

A further two were requested by Maskelyne on 2 April 1772 (RGO6/21/121) for use with the new equatorial sectors that were about to be ordered from Sisson. They were scheduled to be placed in the former summerhouses which were in the process of being converted into domes. The new clocks first make an appearance in the inventories on 14 December 1774. There are several slightly differing versions of the 14 December 1774 inventory, RGO6/21/130–134, RGO4/309/2, RGO/309/4 & RGO4/309/5 and depending on which version you read, on that date, the clocks were either both in the East Dome (former Eastern Summerhouse), or one was in the East Dome and the other in the West Dome (former Western Summerhouse).

An undated inventory taken after 1798 but before 1812 (RS MS372/165) lists the four clocks as being in the Transit Room, the Great Room and the East and West Domes. An amendment in pencil has altered the original entry for the West Dome from ‘An Assistant Clock with a Wooden Pendulum’ to ‘An Assistant Clock without a Pendulum’.

The next known inventory is also undated, but was taken after 1805 but before 1812 (RS MS372/169). This lists one clock as being in the Transit Room, one in the Quadrant Room which is recorded as having been moved from the Eastern (East) Dome, one in the Great Room and one in the West Dome which is now described as having a wooden pendulum.

The supposed appearance of a journeyman clock by Johnson

In his 1975 book, Greenwich Observatory, (1975, p.134), Howse states that two journeyman clocks were purchased from Johnson in about 1818. Howse cites no source and only one such clock attributed to Johnson can be found in the inventories. It is first mentioned in the inventory of 1818, which is the next known inventory to have been taken after the one mentioned above.

The 1818 inventory (RS MS372/170) was taken on 26 June. ‘An Assistant Clock by Johnson’ is recorded as being present in the Circle Room. Three other assistant clocks are also listed, one each in the Quadrant and Transit Rooms, and one with a wooden pendulum in the Great Room. The total number of assistant clocks recorded remains unchanged. The question therefore arises: was one of the Shelton clocks disposed of and replaced by a new one from Johnson, or was the so called Johnson clock actually one of the Sheltons that had perhaps been sent to Johnson for refurbishment, or was one of the clocks omitted by mistake from this and subsequent inventories? The way the inventories are written makes it difficult to be certain. The fact that they were normally always based on the one before and that the descriptions are often vague, can make it difficult to be sure which of the instruments is being referred to. As an example of this, in the 1774 inventory, which comes in a number of slightly different versions (RGO6/21/133, RGO4/309/2, RGO/309/4, RGO4/309/5), two of the Graham regulators are described as ‘A month clock with a compound pendulum, by Shelton, with new Ruby Pallets’.

A slightly later inventory (RGO6/54/14–18), undated, but seemingly taken before 1821, lists the four assistant clocks described in the 1818 inventory, but describes those in the Quadrant and Transit Rooms as having wooden pendulums.

The next full inventory is dated 4 June 1824 (RS MS/371/70) and seems to be as above, though a later amendment seems to suggest the one in the Great Room was moved to join the one already in the Quadrant Room.

The next full inventory seems to have been made in 1830 (RS MS371/71). It lists the presence of three or perhaps four of what are presumed to be the Shelton journeyman clocks. One is listed as being in the Advanced Room, one (possibly two) in the Quadrant Room and one in the Transit Room. There is also one by Johnson, which is still listed as being present in the Circle Room.

The inventories of 1831 and 1840 – a conundrum

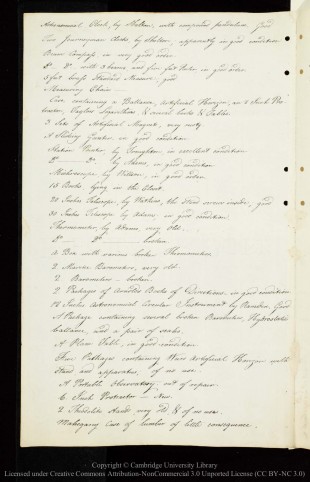

The second page of an undated Board of Longitude inventory (RGO14/13/24). Two Shelton Journeyman clocks are listed in the second line. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

The 1840 inventory (RGO6/54/86) lists all six journeyman clocks that had previously been listed in the 1831 inventory as belonging to the Observatory. All are listed as being in the Transit Room and are cross-referenced back to their previous locations. No maker is mentioned.

In the 1840 inventory, the instruments listed in 1831 as having come from the Board of Longitude are no longer listed separately. Although many are still present at the Observatory, the two journeyman clocks do not appear to be amongst them.

A second copy of the 1840 inventory (RGO39/1) has later amendments which record the loss of two of the six Greenwich Journeyman Clocks: one which was lent to Kew Observatory, and one which was ‘exchanged for a chronometer to Mr Bennet of Greenwich.’ The loan to Kew seems to have occurred in the reporting year 1844/5. In the 1845 annual report Airy states that it had not been used for at least ten years and that it had been lent ‘to be used in conjunction with the electric apparatus mounted there.’ In the reporting year 1855/6, Airy reported that a second Journeyman was also out on loan, this time to the South Eastern Railway Station, for occasionally keeping up the motion of the large galvanic clock there which was also the property of the Royal Observatory. The last mention in the annual reports of these two particular clock loans, is in the reporting year 1856/7.

Later uses of the clocks

With the introduction in the mid nineteenth century of chronographs for recording observations, the journeyman clocks became more or less redundant. From 1843 until 1847, Airy recorded that the Observatory had ‘some journeyman or assistant clocks’ in the introduction he wrote for each of the annual volumes of Greenwich Observations. In the volume for 1848, this was changed to ‘there are some journeyman or assistant clocks, now rarely used’. Much the same phrase was used in the subsequent volumes until 1868 when Airy recorded: ‘there are some journeyman or assistant clocks, two of which, occasionally used in longitude operations, are fitted with contact springs, for the purpose of giving galvanic signals’. Each subsequent volume contained much the same wording until 1890 when Christie changed it to: ‘there are four journeyman or assistant clocks, two of which, occasionally used in longitude operations, are fitted with contact springs, for the purpose of giving galvanic signals’. The entry for 1891 was changed to: ‘there are two journeyman of assistant clocks’. The same wording was used until 1909 which was the last year that an introduction to the Greenwich Observations was published.

Airy gave a description of the modifications that had been made for galvanic use in his write up of the Determination of the Longitude of Valencia in Ireland by Galvanic Signals, in the Summer of 1862, (p.16):

‘For completing the galvanic circuit by which the signal was given, a small auxiliary clock was used at each station; on whose 60-second wheel were fixed 4 pins, which, in the rotation of the wheel, forced into momentary contact a pair of springs carried by an insulating block. The two segments of the galvanic wire, one leading to the battery, the other leading to the long telegraph-wire, were connected with these two springs; and thus, at every 15s nearly, the telegraph-wire was brought for an instant into metallic connexion with the battery, and the galvanic current passed and exhibited its signal on the galvanometers at both stations. The regular recurrence of signals is attended with this great advantage, that the observer is prepared to fix his attention on the signals and on the beats of the transit-clock: at the-same time, by proper adjustment of the rate of the auxiliary clock, the signals are made to fall on all portions of the temporal interval between two beats of the transit clock. As soon as the period of sending signals from one station was terminated, the long wire was disconnected from the clock and was connected with earth, and at the same time the opposite change was made at the other station.’

Harton Colliery and eclipse expeditions

One of the modified Journeyman clocks had previously been taken by Airy to Harton Colliery in 1854 for use in his attempt to determine the mean density of the Earth. Airy took two other clocks with him: a Shelton Regulator borrowed from the Royal Society and the Earnshaw Regulator from the East Dome of the Royal Observatory.

The Shelton journeyman (right) and the Shelton Regulator undergoing testing at Greenwich prior to being used at Harton Colliery. Drawn by Airy with the aid of a camera lucida. Plate XI accompanying Airy's Account of pendulum experiments undertaken in the Harton Colliery, for the purpose of determining the Mean Density of the Earth. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1856 146, 297-355.

In his account of the experiment, Airy makes the following statement about the Journeyman Clock:

‘The journeyman-clock was thus fitted up. Two wires were led into it (one from the galvanic battery, and the other in continuation of the course of the same wire from the journeyman to the next comparison-clock), terminating within the journeyman in a pair of springs which performed the duty of circuit-breaker. Upon the minute-wheel of the journeyman were four pins, which, as the wheel revolved, pressed the two springs together, thus completing the circuit (in that part) at every 15s of the journeyman’s time.’

Although the inventory taken in the mid 1890s doesn’t list any of the clocks as Journeyman of Assistant clocks, there is an entry amongst the items in the Lower Chronometer Room (RGO39/10/53) for three ‘Old clock cases with portions of clocks, formerly used in Harton Colliery Experiments’. One of these, believed to be the Journeyman, is recorded as having been lent to Maunder for the 1896 and 1898 solar eclipses. In the book The total solar eclipse of May 1900, Maunder, the editor, makes a fleeting reference to the clock on p.20:

‘In the corner of our hut was mounted the same signal clock – one of those used in the Harton Colliery experiment of Sir George Airy, but slightly altered for eclipse purposes, and kindly lent by the Astronomer Royal – that we had used in our expedition to Norway [in 1896].’

From what Maunder wrote on the following page, it seems that the clock had been modified to ring the bell every 10 seconds rather than every minute as had originally been the case.

Although it is not mentioned in the inventory, the clock was also used by Maunder for the May 1901 eclipse. In his preliminary account published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Maunder wrote:

‘The times of the 10-second bells of the eclipse clock – which was one of the clocks used by the late Sir G. B. Airy, K.C.B., in the Harton Colliery experiment ...’

Fate of the clocks

The second journeyman mentioned in the 1891–1909 volumes of Greenwich Observations remains to be located in the inventory of the mid 1890s. A possible candidate is a clock that has the terribly vague description: ‘old clock case & wood pendulum’ (RGO39/10/53). The 1911 Inventory (RGO39/4) which is believed to have been the next after that of the mid 1890s is organised differently. Rather than list items room by room, it consists of lists of objects by type. It is also the first of the inventories to appear in the form of a typed list. On p.132, there is an entry: ‘Clock cases, old, with portions of clocks, formerly used in Harton Colliery Experiments’. The number of such items has been typed as three, but amended by hand to two. Listed as being in the Shuckburgh Dome, they have been marked with a C meaning that they were condemned. The next entry in the list is ‘Clock case, old, and wooden pendulum’ This was also recorded as being in the Shuckburgh Dome. However, the words ‘Shuckburgh Dome’ have been crossed out and the comment added ‘not identified’. Like the Harton clocks, this entry has also been marked with a C for condemned.

The ultimate fate of the Greenwich and Board of Longitude Journeymans is unknown. Very few journeyman clocks are known to exist. In 1995, the auctioneers Christie’s suggested that perhaps fewer than five such clocks survive.

Howse records, on p.134 of his 1975 book, Greenwich Observatory, that a clock acquired from the Observatory by the National Maritime Museum (before 1975) was described as a journeyman clock, and may be the one by Johnson. Sounding somewhat sceptical, he describes the clock as having ‘a painted deal case, a painted dial, a wood-rod pendulum, but otherwise a conventional dead-beat movement, now with seconds contacts’. Neither the dial nor the movement have a maker’s mark.

For those wishing to see a Shelton Journeyman Clock, the one from the Radcliffe Observatory is preserved at the Museum of the History of Science at Oxford (Inventory number: 46869). It is thought likely to have been of the same construction as those ordered by Maskelyne.

* The term journeyman seems to have been coined by Maskelyne who used it in his write up of the observations made on the island of St Helena which were published in 1764 on p.373 of Phil. Trans. LIV.

Acknowledgements

The photograph of the second page of an undated Board of Longitude inventory (RGO14/13/24) is reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) 3.0 Unported License courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library. The version on this website, has had its margins cropped and has been further compressed for faster downloading.

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan