…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

People: George Airy, the seventh Astronomer Royal

page under construction

| Name | Airy, George Biddell |

||

| Place of work | Greenwich | ||

| Employment dates |

1 October 1835 – 15 Aug 1881 (see note below re: start date) |

||

| Previous Posts | 1826, Dec 7 |

Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge |

|

| 1828, Feb 6 |

Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Director of the Cambridge Observatory | ||

| Posts | 1835, Oct 1 |

Astronomer Royal | |

| Born | 1801, Jul 27 |

Alnwick, Northumberland | |

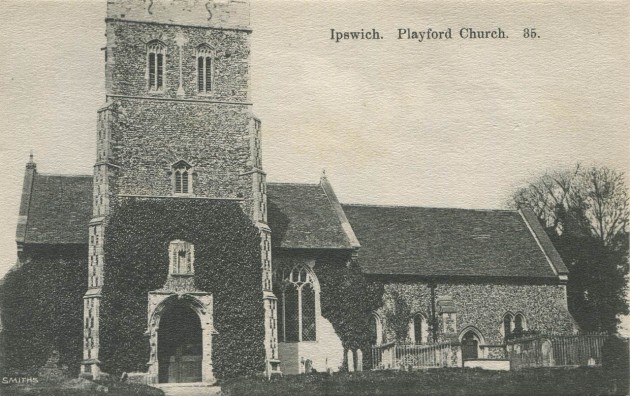

| Died | 1892, Jan 2 | Died at The White House, Greenwich. Buried 7 Jan at Playford, Suffolk |

|

| Known addresses | 1828–1835 | Cambridge Observatory | |

| |

1835–1881 | Flamsteed House, Royal Observatory Greenwich | |

| 1881–1892 | The White House, Crooms Hill, Greenwich |

||

| Wealth at death | £27,713 9s. 9d | Probate: 5 March 1892 | |

| |

|||

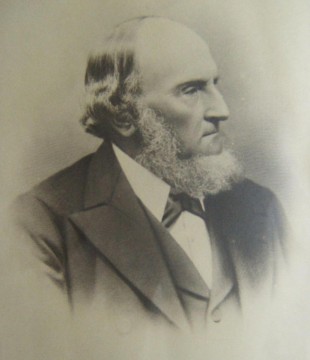

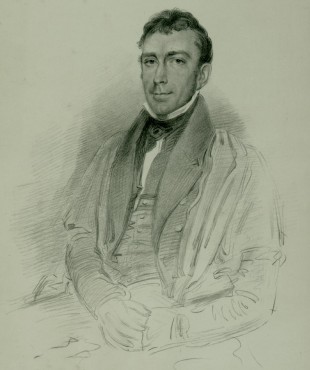

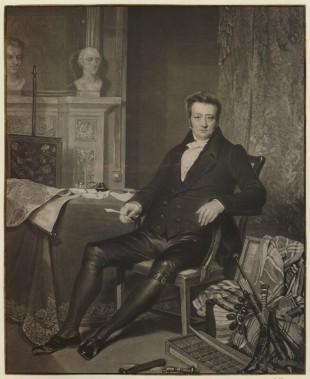

George Airy in 1833 by Isaac Ware Slater, after Thomas Charles Wageman. Lithograph on chine collé published by W Mason, Cambridge & WH Mason, print sellers to the Queen Brighton. Cropped, digitally cleaned and reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence courtesy of the University of Cambridge, Institute of Astronomy Library

During his 45 years in office, Airy kept copies of all his official correspondence. His official papers, are preserved in the Cambridge University Library (RGO6). With a volume of 12 cubic metres and occupying 125 yards of shelf space, they relate to a wide range of subjects. It is largely thanks to Airy’s efforts that Bradley’s manuscript observations were returned to the archives in 1861.

Although Airy’s autobiography was published in 1896, a proper biography is still awaited. Given the range, extent and complexity of Airy related material, it is not the intent of this webpage to give even a potted history. Instead, the aim is to guide the reader towards links to relevant mater on this website and to the large volume of other writings elsewhere.

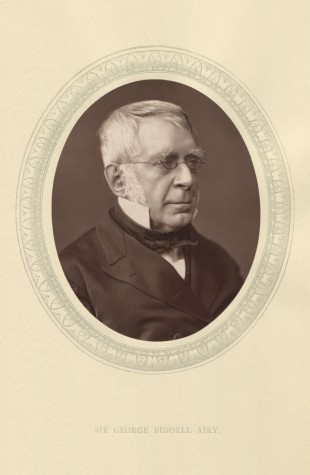

Airy’s Autobiography

Airy's autobiography contained just this one image. Permission to use it in the autobiography was given by Macmillan and Co, who first published the image in the 31 October 1878 edition of Nature and as the frontispiece to Volume 18 where it was titled Sir george Biddell Airy engraved by C H Jeens from a photograph. Following a complaint from the photographer, an apology of sorts was published in the 21 November edition (p.61) which stated that they hadn't known who the photographer was, but that they now understood it was Mr Brothers of Manchester. This was probably Alfred Brothers who had a lifelong interest in photography and astronomy and set up a studio in Manchester in 1856. The photo was probably taken while Airy was attending the meeting of the British Association at Manchester in September 1861

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy (Project Gutenberg)

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy (Internet Archive)

The first link (above) is to a single page containing the complete text. It has the great advantage that the text has been proof read and is quick to search for key words. The second is from Internet Archive and allows the book to be read in its original format. It too is searchable, but searches take longer and errors generated by the optical character reader have not been corrected.

The autobiography is not a conventional one. Although the majority of the words are Airy’s, the text has been put together from a variety of sources of which a manuscript history of his early life, his Reports to the Board of Visitors and his Journal (in which he made daily notes) are the most prominent. All the Reports are available to read online as is the first volume of his Greenwich Journal (1836-1847) which has been provided by the Cambridge Digital Library, complete with a transcript by Daniel Belteki.

Reports of the Astronomer Royal to the Board of Visitors

Astronomer Royal’s Journal, 1836 January to 1847 December (RGO 6/24)

Airy wrote frequently to his wife when he was away. Although Wilfred Airy drew on these and other family letters (now destroyed?), next to nothing is communicated about his relationship with his parents, siblings, wife, children or friends.

The autobiography is strictly chronological, full of facts and tends to leap from one subject to another with each new paragraph. A valuable resource and often a first point of reference for historians, it is hardly a compelling read. It is none the less an interesting one. The decisions made by Wilfred on what material to cut or gloss over has left key questions unanswered and the book rather one dimensional. There is none of the thought provoking analysis that one would hope to find in a biography.

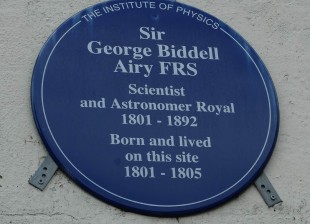

Early life

Attached to the gable wall of 5 Grosvenor Terrace (an early 19th century house) this Blue Plaque (presented by the Institute of Physics and unveiled on 20 October 2003) looks over the site of the house in Alnwick where Airy was born. The Airy house was replaced in the early 19th century. That house was itself replaced by another (the present 80 Clayport Street) in about 1960. Note the incorrect date of 1805. Reproduced under an Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0) licence courtesy of Peter Reed (see below)

As a young man William Airy became foreman on a farm and used his earnings to improve his education. In the mid 1770s, at the age of 24 he obtained a post in the Excise.

The Board of Excise, which was established in 1643, was in charge of collecting duties. These were levied at the point of manufacturing rather than at the point of sale as is typically the case today.

At an administrative level, the country was divided up into areas known as Collections, the number of which varied over time. In England and Wales for example, there were 54 Collections in 1797 and 55 in 1801.

Each Collection was headed by an Officer known as the Collector. Collections, were sub-divided into somewhere between three and seven smaller units known as Districts, each of which was controlled by a supervisor. The Districts were further divided into Rides, Footwalks or Divisions. Rides covered rural areas, where a horse was needed to fulfil the duties. Footwalks or Divisions were in towns and could be covered on foot.

Over the years, William Airy served in several Collections, gradually rising though the ranks. On 15 August 1800, he was appointed Collector of the Northumberland Collection. With his future and a good source of income seemingly secure, he got married six weeks later; the wedding taking place in Suffolk on 30 September. Just over nine months later, on 27 July 1801, the future Astronomer Royal, George Airy, was born.

On 22 October 1802, William was appointed Collector of the Hereford Collection. It was at Hereford, that Airy’s three siblings Elizabeth (1803–1879), William (1807–1874) and Arthur (1809–1811) were born. In 1810, the family moved again when William senior was appointed Collector of the Essex Collection. The family set up home in Colchester, where they lived in George Lane (the present George Street: the site being occupied by the present numbers 7 & 8).

According to William Ashworth, (Customs and Excise, 2003) the Excise Department was ‘… characterized by a well-trained army of officers subject to strict regulations, within a clearly structured hierarchy … characterized by an element of merit, a regular wage, and an emphasis on a technical method of revenue collection.’ The same description might well be used to describe the way that the Royal Observatory was run under Airy.

In 1813, at the age of 63, Airy’s father lost his job as Collector of Excise, leaving the family in much reduced circumstances. Although the reason for William Airy’s dismissal is not presently known, it is suspected that it may have been the result of an administrative error on his part. The Excise records held at the National Archives may reveal the reason. They will be examined when the closure of the Archives due to COVID-19 is lifted. If his father was dismissed due to an administrative error, it would help explain why Airy always paid great attention to detail, particulary as far as public accountability and the spending of public money were concerned.

Arthur Biddell – the well connected uncle who opened doors

In Hereford, Airy attended an elementary school. In Colchester, he inititially attended the school that was run by Byatt Walker in Sir Isaac’s Walk. In 1814, the year after his father lost his job, Airy was enrolled at the endowed grammar school, where he remained until 1819. At that time, the school was in Culver Street (now Culver Street East), about three minutes walk away from his home in George Lane. According to Trevor Hearn (Vitae Corona Fides, 2018), in 1818, the school had 30-40 pupils and the fees for day scholars were £10 a year. Private scholars were charged considerably more.

It was possibly in the winter of 1812/13, when he was just eleven years old that Airy first went to stay for a few weeks with his mother’s brother, Arthur Biddell, who lived at Playford, a village about 20 miles north-east of Colchester. The two got on really well and a pattern of extended twice yearly visits each summer and winter (lasting about four months in total), became the norm.

Born in 1783, Arthur Biddell was the youngest of George Biddell’s children. When he was 16, his father died, leaving him a farm at Bradfield St George and a share in two others with his brother. In 1808, he decamped some 20 miles or so to Playford in order to take on the tenancy of Hill House farm, which was owned by the Earl of Bristol. He also became the Earl’s local agent and in later years took on the tenancies of two more of the Earl’s farms in the village: Lux Farm (c.1821) and Kilne Farm (c.1829).

Thomas Clarkson by Charles Turner, after Alfred Edward Chalon. Mezzotint, published 1828. © National Portrait Gallery, London. The painting by Chalon, a watercolour, is now in the collections of Hull Museums (Accession No. KINCM:1980.840) who date it as c.1790. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence (see below)

In 1817, Biddell married Jane Ransome, daughter of Robert Ransome (1753-1830), who had founded the agricultural engineering firm Ransomes of Ipswich in 1789. Biddell also turned his hand to inventing agricultural machinery and in 1822, was awarded a silver medal by the Royal Society of Arts.

Meanwhile, back in 1812, the civil engineer and millwright, William Cubitt (1785–1861) whom Biddell had known for a while, had joined Ransomes going on to become its chief engineer and later a partner, a position he retained until about 1817.

It was the time spent with his uncle and his uncle’s friends and guests at Playford – the Ransomes, Clarkson and Cubitt as well as the Quaker poet Bernard Barton – that shaped not only Airy’s immediate future, but also his wider outlook and his lifelong interest in engineering matters of all types.

Airy rightly acknowledges his debt to his uncle. In his autobiography, Airy records

‘On May 26th [1860] my venerable friend Arthur Biddell died. He had been in many respects more than a father to me: I cannot express how much I owed to him, especially in my youth’.

By contrast, whilst acknowledging that his father ‘was a man of great activity and strength, and of prudent and steady character’ there is no acknowledgment or even suggestion that anything his father did impacted on the way in which he was to run his two Observatories.

The Cambridge years (1819–1828) – seeking financial independence

Meeting Clarkson was a fortuitous event in Airy’s life, for it was Clarkson who helped pave the way for him to go to university at Cambridge.

Admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge as a sizar at the age of 18 in March 1819. Matriculated Michaelmas 1819, Scholar 1822, Ist Smith's Prizeman, Senior Wrangler & B.A. 1829, M.A. 1826. Fellow 1824.

Contemplating a proposed new post at Greenwich

In July 1822, following a request from the Astronomer Royal, John Pond, a proposal was put forward to the Admiralty by the Visitors, (who prior to 1830 consisted of the President and Council of the Royal Society), for two more assistants to be employed so that observations could be ‘continued without disruption though the whole of the twenty four hours’ and then speedily reduced (RGO6/22/120). On the strength of this, the following month Pond took on two new assistants on a temporary basis (Thomas Glanville Taylor and William Richardson).

The Admiralty responded to the Visitors’ proposal in March 1823. Whilst agreeing in principle to two extra staff, they proposed that rather than the lowly type of assistant that was currently being employed, the new assistants should be of a superior class with a university education and paid accordingly, with the salary of ‘the First Assistant to commence at £300 a year and to increase by £10 a year to [a maximum of] £500’. (RGO6/22/124). At their meeting in June, the Visitors endorsed the proposal for assistants of a superior class to be employed (the minutes implying that the President and the whole of the Council agreed) (RGO6/22/127). In December 1823, the Admiralty sent the proposal for approval to His Majesty in Council, suggesting to the Visitors that the posts should be filled as quickly as possible after approval was given (RGO6/22/130).

In early 1824, John Herschel conveyed this news to Airy and suggested that he would ‘be an excellent person for the principal place’. To find out more, Airy went to London on 7 February to be present at one of Sir Humphrey Davy’s Saturday evening soirées and to find our more from him as President of the Royal Society and also from Thomas Young, another of the Visitors (who had taken over as Superintendent of the Nautical Almanac from Pond in 1818). When Airy found ‘that succession to the post of Astronomer Royal was not considered as distinctly a consequence of it’, he was unimpressed and after staying overnight with Sir James South returned to Cambridge the next night. In the end, no assistants of a superior class were appointed while Pond remained Astronomer Royal.

The Cambridge years (1828–1835) – financial independence and marriage to Richarda Smith

Richarda Airy. Photo by Cundall & Downes, Nov 1860. © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), details below

The resignation of John Pond and the appointment of Airy as Astronomer Royal

In the autumn of 1835, Airy succeeded John Pond as Astronomer Royal. It is often said (without citing the evidence) that Pond was forced, or in more extreme cases compelled, to resign. Patrick Moore in his book Astronomy (1961) states that Pond ‘neglected his duties so badly he was compelled to resign’. John Hunt in his article The handlers of time (1999) states Pond ‘was harassed into retirement in 1835’, and appears to have copied the phrase from Eric Forbes (Greenwich Observatory Vol.1, 1975). Allan Chapman in his book Comets, Cosmology and the Big Bang (2018) uses neither the word force nor the word compelled, but merely states that Pond ‘retired on health grounds’. It is certainly true that Pond suffered from ill health and it’s true that he resigned, but did he neglect his duties? And was one the consequence of the other? And when exactly and under what circumstances did he resign ... and did he perhaps resign not because he had neglected his duties or because of his health, but because he was made an offer that was too good to refuse?

The resignation of an Astronomer Royal was unprecedented. All five of Pond’s predecessors died in post – Flamsteed at the age of 73, Halley at the age of 85, Bradley at the age of 69, Bliss at the age of 63 and Maskelyne at the age of 78. In 1835, Pond was just 67 years old. There was no established process for an Astronomer Royal to retire, or to be removed from office, or to be awarded a pension.

Appointed as Astronomer Royal in 1811, Pond’s health had never been good. As early as December 1818 there was speculation that his post might soon become vacant. Charles Babbage thought that John Herschel would be a good candidate, but at that time, Herschel did not think himself qualified. Five years later, at the end of 1823, there was again speculation that Pond might resign, partly because of his health and partly because of his resisitance to the imposition at the Observatory of a new superior class of Assistant with a university education. At this point, Herschel declared to James South, that were the post of Astronomer Royal to become vacant, he would be ‘anything but disinclined to offer myself for it’. He followed this up by saying that although he would be interested in the post if it were to become vacant, he would not wish to work with Stephen Lee, who was apparently then under consideration for appointment as one of the superior Assistants.

Having taken charge of the Cambridge Observatory in 1828, Airy had rapidly gained a reputation for its efficient running, causing Heschel to change his tune. In 1831, he told William Stratford that if the position of Astronomer Royal should become vacant, he believed that Airy would be interested and that he would gladly support such a candidacy.

In the absence of materials that document the events leading up to Pond’s resignation from his perspective, it is necessary instead to look at events solely from Airy’s perspective. It would appear that the process of recruiting him began in May 1834, more than a year before Pond left office. The following extracts are taken from Airy’s autobiography. They are based on notes in his Cambridge journal and correspondence now preserved in the Observatory archives (RGO6/1/144 onwards)

‘On May 10th [1834] I went to London, I believe to attend one of the Soirées which the Duke of Sussex gave as President of the Royal Society. The Duke [who was also the chairman of the Observatory’s Board of Vistiors] invited me to breakfast privately with him the next morning. He then spoke to me, on the part of the Government, about my taking the office of Astronomer Royal. On May 19th I wrote him a semi-official letter, to which reference was made in subsequent correspondence on that subject. ... On Aug. 25th Mr Spring Rice (Lord Monteagle) wrote to me to enquire whether I would accept the office of Astronomer Royal if it were vacant. I replied (from Keswick) on Aug. 30th, expressing my general willingness, stipulating for my freedom of vote, &c., and referring to my letter to the Duke of Sussex. On Oct. 8th Lord Auckland, First Lord of the Admiralty, wrote: and on Oct. 10th I provisionally accepted the office. On Oct. 30th I wrote to ask for leave to give a course of lectures at Cambridge in case that my successor at Cambridge should find difficulty in doing it in the first year: and to this Lord Auckland assented on Oct. 31st. All this arrangement was for a time upset by the change of Ministry which shortly followed.

... in dining with the Duke of Sussex in the last year, I had been introduced to Sir R. Peel, and he had conversed with me a long time, and appeared to have heard favourably of me. On Feb. 17th [1835] he wrote to me an autograph letter offering a pension of £300 per annum, with no terms of any kind, and allowing it to be settled if I should think fit on my wife. I wrote on Feb. 18th accepting it for my wife. In a few days the matter went through the formal steps, and Mr Whewell and Mr Sheepshanks were nominated trustees for my wife. The subject came before Parliament [on 16 March], by the Whig Party vindicating their own propriety in having offered me the office of Astronomer Royal in the preceding year; and Spring Rice’s letter then written to me was published in the Times, &c.

The Ministry had been again changed in the spring [of 1835], and the Whigs were again in power. On June 11th Lord Auckland, who was again First Lord of the Admiralty (as last year), again wrote to me to offer me the office of Astronomer Royal, or to request my suggestions on the filling up of the office. On June 15th I wrote my first reply, and on June 17th wrote to accept it. On June 18th Lord Auckland acknowledges, and on June 22nd the King approved. Lord Auckland appointed to see me on Friday, June 23rd, but I was unwell. I had various correspondence with Lord Auckland, principally about buildings, and had an appointment with him for August 13th. As Lord Auckland was just quitting office, to go to India, I was introduced to Mr Charles Wood, the Secretary of the Admiralty, with whom principally the subsequent business was transacted. At this meeting Lord Auckland and Mr Wood expressed their feeling, that the Observatory had fallen into such a state of disrepute that the whole establishment ought to be cleared out. I represented that I could make it efficient with a good First Assistant; and the other Assistants were kept. But the establishment was in a queer state. The Royal Warrant under the Sign Manual was sent on August 11th. It was understood that my occupation of office would commence on October 1st, but repairs and alterations of buildings would make it impossible for me to reside at Greenwich before the end of the year. On Oct. 1st I went to the Observatory, and entered formally upon the office (though not residing for some time). Oct 7th is the date of my Official Instructions.

I had made it a condition of accepting the office that the then First Assistant should be removed, and accordingly I had the charge of seeking another. I determined to have a man who had taken a respectable Cambridge degree.’

The text of Spring Rice’s letter as recorded in Hansard was as follows. In all material respects it is identical to the original (RGO6/1/147):

Downing-street, August 25, 1834.

MY DEAR SIR.—It is highly probable that a vacancy may take place very shortly in the office of Astronomer Royal. If this event occur[s], it will be of course the duty and the object of the Government to make such a selection as shall be most conducive to the interest of science, and as shall secure to our national astronomical establishment and its observations, the greatest respect and authority throughout Europe. On these principles it is more than natural that the Government should be desirous of knowing whether the appointment is one which you would accept; as it would be most gratifying to us all to have an opportunity of marking the admiration which we feel for your eminent attainments, and the respect which is justly due to your character as an individual. As a Cambridge man, I am fully aware that to our University the loss of one of its greatest ornaments cannot but be felt as irreparable; but we ought not to be selfish, we should think of England as well as of Cambridge; and I trust there is not one of our scientific friends who will not feel that in selecting a new Astronomer Royal, it is towards you that the earliest attention of his Majesty's Government should be directed, less in justice to science, than to the credit and character of the country.

Pray let me hear from you at your earliest convenience, and believe me, &c.

T. SPRING RICE,

To rev. Professor Airy, Cambridge.

In summary then, Airy was sounded out about the post in May 1834 and informally offered and accepted the job in August 1834. He was formally offered the post on 11 June 1835, and accepted it on 17 June. Although the news wasn’t officially announced until 11 August (the date the Warrant was issued), the news was circulating in the press by early July. The Bury and Norwich Post carried the story on 8 July:

‘Professor Airy has been appointed to the distinguished situation of Astronomer Royal, vacant by the resignation of Mr. Pond, with a salary of £800l. [£800] a year. It may safely be predicted that the office will derive as much distinction from the occupant, as the occupant from the office’

When Airy was offered the post on 11 June 1835, Pond had not actually resigned. He had merely indicated to the First Lord of the Admiralty that he was willing to do so (RGO6/1/156). It has to be supposed that by the end of the month he had formally tendered his resignation. And presumably if he wasn’t already involved in some sort of negotiation he would have known that serious efforts were afoot to replace him as far back as August 1834 when Spring Rice read out his letter in parliament. Interestingly, in a letter to Herschel dated 19 October 1834, Airy states that Pond had been asked to resign. Further research is required to find out who asked him and on what authority.

The wording of the Warrant by which Airy was appointed as Astronomer Royal harked back to Flamsteed's time. Flamsteed was appointed as ‘Our Astronomical Observator’ and so too were all the Astronomers Royal up to and including Airy. Using words that were almost identical to those used for his predecessors, the Warrant stated:

‘We being well satisfied of your learning, your industry and great skill and ability in the science of Astronomy, do by these presents, consitute and appoint you Our Astronomcial Observator in our Observatory at Greenwich during Our pleasure; requiring you forthwith to apply yourself with the most exact care and diligence to the rectifying of the tables of the motions of the heavens, and the places of the fixed stars, in order to find out the so much desired longitude at sea for the perfecting the art of navigation; and it is our Will and Pleasure that you forthwith take possesion of our said Observatory ...’

The Warrant, which also stated that Airy would be paid a salary of £800 per annum, was signed and sealed by King William IV at the Court of St James’s on the 11 August 1835.

Bizarly, although the Warrant was signed and legally came into effect on 11 August, it was understood by both Airy and the Admiralty as the date on which he would actually take up office until 1 October. So when did Pond formally leave? We don’t actually know. We do know however that the published observations up to the end of September 1835 were published under his name. And what was the reason for Pond’s departure? Again, we don’t know. Pond died a year after leaving office. His obituarist however recorded that:

‘For several years Mr. Pond was sbject to very painful and harassing complaints. He resigned his office towards the close of 1835, when a retiring pension of 600l [£600] was granted him for life.’

At that time, there was no automatic pension that went with the job. The pension offer was a generous one and equal in size to Pond’s basic salary. Regretably, the obituarist’s statement is ambiguous. So, did Pond resign because he was made an offer of a pension that was too good to refuse, or did he resign not expecting a pension and was then pleasently suprised to receive one? This writer believes it was the former and that Pond was paid off in order to remove him from office

Although Airy commenced work at Greenwich on 1 October, he did not move in until the end of the year following alterations to the accomodation which included the addition of a single story wing with three good sized rooms on the west side of Flamsteed House. In the meantime, he and his family remained living at the Observatory at Cambridge and visited Greenwich once a week, leaving his new First Assitant Robert Main in charge for the rest of the time. It was only on 14 December that he formally resigned his post at Cambridge.

The 1835 Warrant appointed Airy as William IV’s ‘Astronomical Observator’ Astronomcial. On William’s death in June 1937, Airy's appointment would have technically lapsed. Airy being Airy therefore took steps to obtain a new Warrant from the incoming monarch as he would have wanted complete clarity regarding his own position. Interestingly, none of his predecessors ever had their appontment reaffirmed on the accession of a new monarch, but Airy would almost certainly have been aware of the problems that arose because of earlier failures to renew the warrants for the Board of Visitors. The most striking about the new Warrant carrying Victoria's signature and orfficial seal is that the text of appears to be written our by Airy himself. The new Warrant was signed at the Court of St James’s on 15 November 1837. Unlike the Warrant of 1835, there was no mention of his salary. Both Warrants are perserved in the archives at Cambidge (RGO6/1/193 & 195).

Family

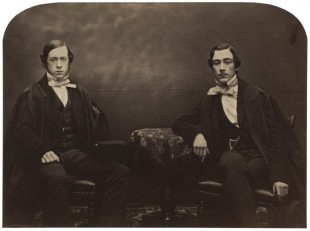

Hubert and Wilfrid Airy by W. Nichols. Albumen print on card mount, c.1860. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence (see below)

George Richard (1831–1839)

Elizabeth (1833–1852)

Arthur (1834–1839)

Wilfrid (1836–1925)

Hubert (1838–1903)

Hilda (1840–1916)

Christabel (1842–1917)

Annot (1843–1924)

Osmund (1845–1929)

At home with the Airys

In 1828, following the death of his father the previous year, Airy’s mother and sister, Elizabeth, moved from Bury to join him at the Cambridge Observatory where he had just moved in. They remained living there until Airy’s marriage to Richarda in 1830, when at his mother’s insistance she moved out. Accompanied by Elizabeth she moved to Playford, where Arthur Biddell arranged for them to stay in one of his properties – the farm-house at Luck’s Farm.

In 1839, following the death of Airy’s two eldest sons, his mother and sister moved in with him again, this time, to the Observatory at Greenwich. Both stayed there until they died; his mother in 1841 and his sister in 1879.

The Observatory was sufficiently large for guests to stay overnight. Richarda’s sister, Elizabeth, made a number of drawings of the Observatory, thirteen of which are preserved in the acrchives at Cambridge, where there is also a srawing by Richarda and two more by their sister Caroline. Their importance today in understanding the appearance and evolution of the Observatory buildings before the advent of photography cannot be underestimated.

Looking eastwards from the garden behind Flamsteed House. The two figures are probably Richarda and one of her children. The structure with the sloping roof, Maskelyne's Advanced Building, was later replaced by the South Dome (built to house Airy's new Altazimuth Telescope). Pencil drawing by Elizabeth Smith, 20 July 1838. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

As well as family, Airy played host to numerous other visitors in his capacity as Astronomer Royal. Amongst those who stayed the night was the American Astronomer, Maria Mitchell. The details of her visit in 1857 were recorded by her in her journal and subsequently published. Other visitors were Captain (later Admiral) William Henry Smythe (1788–1865), (a distinguished astronomer and a member of the Observatory’s Board of Visitors), who visited with his family. His daughter, Henrietta (1824–1914) painted a number of watercolours in the 1840s, one of which is reproduced below.

Extracts from the journal of Maria Mitchell

Digital images of the drawings and watercolours by the extended Airy family

Maintaining a Suffolk and Playford connection

In his autobiography Airy writes that in 1837 he ‘introduced Arthur Biddell to the Tithe Commutation Office, where he was soon favourably received, and from which connection he obtained very profitable employment as a valuer.’ He also writes that in the same year, ‘Arthur Biddell bought the little Eye estate for me’. A precise date is not given, nor is its location, nor is there any infromation as to whether the estate that was being sold through the auctioneers Biddell and Blencowe with whom there were family connections (this Biddell being another uncle and Arthur’s brother). Unfortunately, it is also not clear if it was bought by Arthur Biddell as a gift, or if he was merely acting for Airy in its purchase (different historians have come to different conclusions). Either way, the estate seems to have been an investment property which consisted of a house, associated farm buildings and presumably some land, all of which appear to have been rented out. Known to be near a town, it was probably near Eye, a small market town about 20 miles due north of Playford.

On 18 April 1840, disaster struck when all the buildings except the house were burnt down in a fire that was started accidently. Nobody was hurt, but a number of animals died in the blaze. According to the 22 April edition of the Bury and Norwich Post (p.2) both Airy and his tenant (Mr Case of Thorndon, near Eye) were insured. In his autobiography, Airy states that he incurred a loss of £350. It is not clear if this was the size of his insurance claim or it this was by how much he was out of pocket after the insurers had paid out. Airy’s financial affairs are rarely mentioned in his autobiography and it is not presently known for how long Airy continued to own the estate. There are just three mentions of the Eye estate in the autobiography: the last of these being a letter he wrote on 23 April after visiting the burnt out remains with Arthur Biddell the previous day.

Meanwhile, on 24 June 1839 Airy’s son second son, Arthur, died at Greenwich. Rather than having him buried locally, Airy arranged for him to be buried in the churchyard at Playford. On 28 June, the day of the funeral, Airy’s first son, George was not well. He died a few days later on 1 July and was buried alongside his brother on 11 July.

It was probably only a matter of time before Airy was going to seek a place of his own in Playford where he could stay independently of his uncle and his, by then, extensive family. He acquired what he later described as his cottage in either 1843 or 1844. Following the addition of a new extension, he slept in the cottage for the first time on 23 July 1846. He slept there for the last in December 1891. Following his death, the house remained in the family until the death of his granddaughter, the artist Anna Airy, in 1964.

The cottage as purchased by Airy. Title page from Bernard Barton's Poems (4th edition), 1825. Courtesy of University of California (via internet archive) with grateful thanks to Brian Seward who first identified and republished the image

The extension to Airy's cottage in about 1905. The path on the right leads up to the church, which can just be seen behind the trees in the centre of the image. "Christchurch" Pictorial Postcards "Naturette" Series

Playford Village website has several major articles by historian Brian Seward about houses in the village, they include the following (which all download as pdf files):

Arthur Biddell of Hill House Farm

The Airy family at Playford

Thomas Clarkson of Playford Hall

Societys and honours

Airy’s Pay as Astronomer Royal

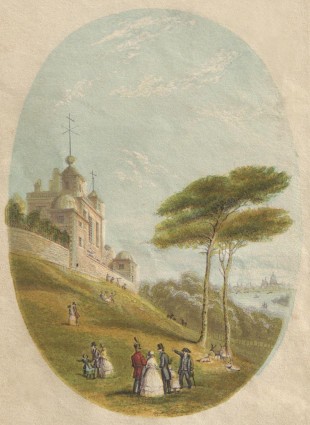

London, from Greenwich Observatory. Printed in oil colours by George Baxter, patentee, 11, Northampton Square. Frontispiece to The child's companion and juvenile instructor New Series, 1848. (Dimensions of oval: 9.1 x 6.6 cm)

Pond’s basic pay from 1831–1835 was £600 a year. In addition to this however he was paid an allowance of £100 a year as Superintendent of Chronometers (a post which he had been required to take on in 1821). He was also given free use of Flamsteed House and paid an allowance for coals and candles (probabaly from the date he was appointed, but certainly by 1815 and worth £200 a year in 1835), from which he was also expected to provide for the non-residential as well as the residential parts of the Observatory.

Airy was was paid at a new consolidated rate of £800 a year plus house, with no separate allowance for either coals and candles or as the new Superintendent of Chronometers. Although the headline figure is on the face of it a third more than what Pond was paid, the reality, is that overall, he was paid about the same amount.

Airy was first sounded out about his willingness to take on the office of Astronomer Royal in May 1834. He provisionally accepted the appointment on 10 October 1834, accepting it formally on 17 June 1835. In February 1835, while he was still still at the Observatory at Cambridge, he was offered a pension of £300 a year form the Civil List by the Prime Minister with the option of either taking it himself, or having it settled on his wife Richarda. He chose the latter. It has to be a matter of some debate as to whether or not the pension should be regarded as an extension of Airy's pay as Astronomer Royal. Given that pensions from the Civil List were granted to all his predecessors back to the time of Halley, it seems not unreasonable to regard it as such.

Airy negotiated a pay rise in 1856, taking his salary to £1000. When Richarda died in 1875, her pension ceased. Airy however managed to persuade the Admiralty to raise his pay by £200 to £1200 a year to compensate.

On his retirement, Airy would, under ordinary circumstances have been entitled to a pension equal to two-thirds of his salary and emoluments. Instead, under Section nine of the Superannuation Act, 1859 paid he was paid a special Retired Allowance of £1100 per annum in recognition of his services.

The post of First / Chief Assistant

From 1675 until Pond’s arrival in 1811, the Astronomer Royal normally had the help of a single paid assistant – the main exception being the period 1720–1742 while Halley was in office, when there are thought to have been none. Under Pond, the number of assistants was gradually increased to six, with the most senior becoming known as the First Assistant. In about 1870, the term Chief Assistant began to be used instead, probably to avoid confusion with the new grade of First Class Assistant that was about to be created.

The first First Assistant (Taylor) acquired the position by default as the longest serving member of staff. Having joined the Observatory in 1807, he was still in post in 1835, but his days were numbered. When first sounded out about the post of Astronomer Royal in 1834, Airy had idicated that he would like Taylor to be removed (RGO6/1/145). In the letter dated 15 June 1835 that he wrote to Lord Auckland (First Lord of the Admiralty) before finally accepting the post, he listed the changes he would want to make at the Observatory (RGO6/1/158). His list began as follows:

‘The first, which I consider absolutely necessary, is the removal of the present first assistant Mr. taylor. He is a drunkard, he has lost his authority over the other assistants by having recourse to them (as I believe) for the assistance of his son Henry Taylor in a scandalous business, and he is under the accusation (printed as I have heard, in some perodical) of receivng bribes from chronometer makers.’

Taylor was duly pensioned off and Airy appointed Robert Main to replace him. Over the years, Airy had three different First / Chief Assistants. They were:

1835–1860 Robert Main (appointed 28 September)

1860–1870 Edward Stone

1870–1881 William Christie (promoted to Astronomer Royal on Airy’s retirement)

From Main’s appointment onwards, with just one exception, all subsequent First and Chief Assistants until Atkinson’s appointment in the 1930s were exceptional maths graduates from Cambridge who tended to be recruited into post more or less straight from university. All were wranglers i.e. had first class degrees. Main was sixth wrangler (sixth in his class), Stone was fifth wrangler and Christie was fourth wrangler. All three went on to run their own observatories.

Pay and staffing

The following pages include a detailed breakdown of the staffing structures that were in place during Airy’s time in office:

Overview – a guide to grading and staffing structures

The Assistant grades

The Superintendent posts

The post of Computer

The Industrial Grades – labourers, night watchmen, mechanics, gardeners, cleaners and others

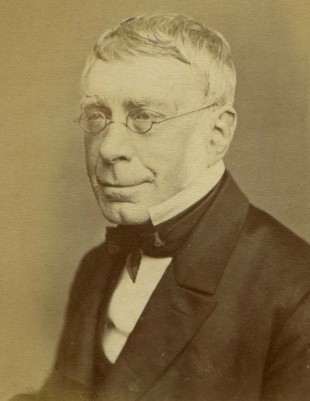

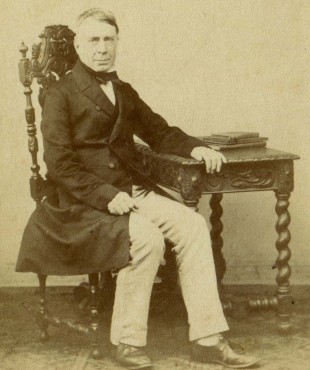

George Airy c.1867. Carte de visite by John Watkins, photographers to the Queen, 34 Parliament Street, London, S.W. (partly cleaned and cropped). A similar portrait by Watkins was published as a whole page woodcut by The Illustrated London News on 4 January 1868

Throughout the 1860s, there was a general feeling of discontent amongst the established staff that they were underpaid compared to other parts of the Civil Service. Royal approval for a new structure and pay scales was eventually given on 29 June 1871. As part of the deal, the separate housing allowance was discontinued. Whilst many pay deals over the years were largely cost neutral, this deal came at significant cost to the Treasury. It gave the assistants not only an immediate increase of between 18 and 67% over their previous pay and housing allowance, but also guaranteed annual increments.

For a detailed breakdown of the pay structures during Airy’s time in office, the following pages should be consulted:

Assistants employed at the Observatory during Airy’s period in office (excluding First/Chief Assistants)

Inititally, Airy had a total of six established Assistants (including the First Assistant). This was increased to seven when the Altazimuth Telescope was erected in 1847. Following the 1871 restructuring, the number of established posts at different levels were as follows.

1 Chief Assistant

2 First Class Assistants

3 Second Class Assistants (increased to 4 in 1873)

1 Superintendent of Mag & Met

1 Magnetic Assistant

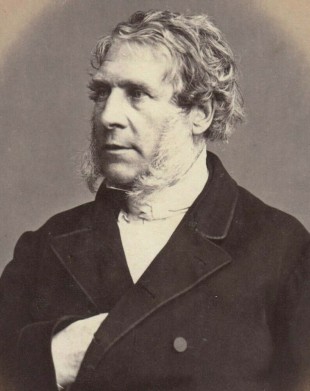

James Glaisher – the best known of all the nineteenth century Assistants, primarily on account of his ballooning exploits and pioneering work in meteorology. Glaisher started working for Airy in 1833 and moved to Greenwich at the start of 1836. Shown here at the height of his fame he resigned in a huff in 1874. His wealth at death was one third more than that of Airy. Whole plate albumen photograph by an unknown photographer, courtesy of The Library of Nineteenth-Century Photography

Edwin Dunkin – the longest serving of Airy's staff. Dunkin joined the Observatory as a Computer in 1838 and rose through the ranks. He was promoted to Chief Assistant on Airy's retirement. He retired in 1884. Airy regarded him as a safe pair of hands. From The Leisure Hour (1898)

In 1840, a new Magnetical and Meteorological branch was created headed by the Sixth Assistant James Glaisher as Superintendent. Initially, three assistants were funded, including one to cover Glaisher’s work in the Circle Department but these numbers were later reduced. The two different funding sources gave rise to two different classes of assistants – the Astronomical ones who were on the establishment and the Magnetical ones who were not. Initially, the Magnetical Assistants were paid £120 a year compared to the £100 plus £30 housing allowance of the more junior astronomical assistants. Glaisher however was paid as an astronomical assistant until the financial year 1868/9, with his pay initially topped up from the Civil Services Vote. When the pay of most of the astronomical assistants began to increase in the 1860s, that of the Magnetical Assistant remained frozen at the 1840 rate.

Airy’s Astronomical Assistants and date of appointment:

1811 John (Thomas) Henry Belville

1822 William Richardson

1825 Thomas Ellis

1825 William Rogerson

1830 Frederick Walter Simms

1836 James Glaisher*

1845 Edwin Dunkin**

1847 Hugh Breen (Jnr)**

1852 John Charles Henderson**

1853 William Ellis

1854 Charles Todd

1855 George Stickland Criswick

1856 William Thynne Lynn

1859 James Carpenter

1873 Arthur Matthew Weld Downing

1873 Edward Walter Maunder

1875 William Grasett Thackeray

1881 Thomas Lewis

* Superintendent of Magnetical & Meterological Department from 1840, but still technically employed as

an Astronomical Assistant until 1871

**Promoted from post of Magnetic Assistant

Magnetic Assistants recruited by Airy

1840 Edwin Dunkin*

1840 John Russell Hind

1840 James Paul**

1844 Hugh Breen (Jnr)*

1844 Charles Dilkes Lovelace

1845 Thomas Downs***

1846 George Humphreys

1848 John Charles Henderson*

1852 Thomas Downs***

1856 Willliam Carpenter Nash

* Later promoted to the established post of sixth / seventh astromomical assistant

** Deployed until 1842 as a replacement for Glaisher in the Circle Department and from then

until his resignation in 1844 as a Magnetic Assistant

***Demoted to the role of Computer in 1848 following a downsizing of the department. Re-employed as a Magnetic Assistant in 1852

The power of patronage – the Greenwich Cambridge Axis and beyond

Additions and alterations to the buildings at Greenwich

During his time in office, Airy made significant alterations and extensions to the following buildings, all of which survive.

Flamsteed House and the Summerhouses

The Meridian Building

The stables (formerly the Garden House)

Airy also erected the following buildings from scratch. Of these buildings, only the Great Equatorial Building survives.

A new Magnetic Observatory

The Great Equatorial Building

The New Library

Workshops, sheds and other miscellaneous buildings

The South Dome (centre) was erected in 1844 to house Airy's new Altazimuth Telescope. More can be read about the South Dome in the link to the Meridian Building above. Watercolour painting by Henrietta Smythe c.1845-49. © The Scout Association Heritage Collection (see below)

Telescopes designed by Airy

In all, Airy designed seven different telescopes. It was his long association with Arthur Biddell, the Ramsomes and William Cubbitt that began in his formative years together with his complete confidence in his own ability that made it completetly natural for him to come up with the design principles of the telesopes himself rather than to rely on someone else to do it for him.

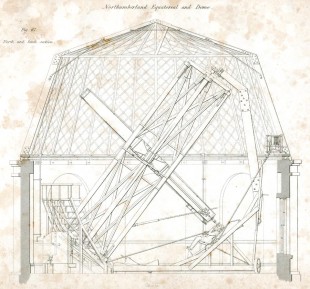

The Northumberland Equatorial at Cambridge. The Great Equatorial at Greenwich has many design similarities. Engraving by J. Basire. Cropped from plate XIX of Airy's Account of the Northumberland Equatoreal and dome attached to the Cambridge Observatory(1844). Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence courtesy of the University of Cambridge, Institute of Astronomy Library

‘The inauguration of the New Equatoreal [the Merz 12.8-inch Visual Refractor] will terminate the entire change from the old state of the Observatory. There is not now a single person employed or instrument used in the Observatory which was there in Mr. Pond’s time, nor a single room in the Observatory which is used as it was used then. In every step of change, however, except this last, the ancient and traditional responsibilities of the Observatory have been most carefully considered: and, in the last, the substitution of a new instrument was so absolutely necessary, and the importance of tolerating no instrument except of a high class was so obvious, that no other course was open to us. I can only trust that, while the use of the Equatoreal within legitimate limits may enlarge the utility and the reputation of the Observatory, it may never be permitted to interfere with that which has always been the staple and standard work here.’

Throughout his time as Astronomer Royal, Airy was keen not to take on work that exceed the remit of the Royal Warrrant by which he had been appointed and he alluded to this several times over the years in his Reports to the Visitors.

The six telescopes designed and completed during his tenure as Astronomer Royal were:

Airy’s Zenith Sector – designed for the use of the Ordnance Survey (1841/2)

Airy’s Altazimuth Telescope (1847)

Airy’s Transit Circle (1850)

Airy’s Reflex Zenith Tube (1851)

Merz 12.8-inch Visual Refractor (1859)

Airy’s Water Telescope (1870)

Clocks and other instruments designed by Airy

Eclipse and other expeditions

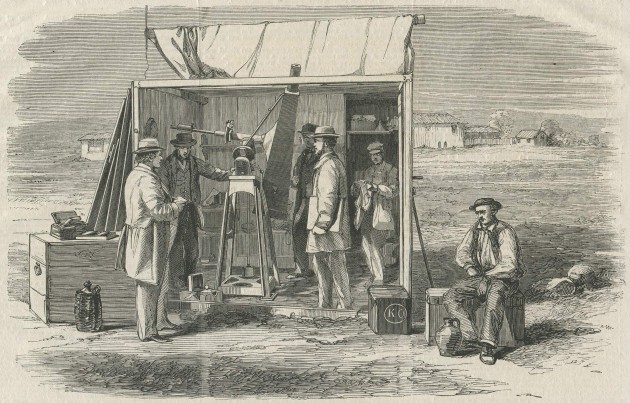

The Kew Photoheliograph at Rivabellosa. Left to right: De La Rue, Beckley (observing the chronometer at his feet), Clarke (holding a taper to burn the thread which triggered the exposure), Reynolds (holding a plate holder ready to place in telescope), Downes (who is standing in front of the entrance to the dark room and who prepared and developed the plates) and unknown (fictitious?). The 'lightweight' iron pedestal was left behind when the instrument was returned to England. Copied from a photograph with reasonable accuracy and a slight degree of rearranging, this woodcut was published in the The Illustrated London News on 25 August 1860 (p.170). Prior to the photograph being taken, the front boards of the observing hut were removed to allow the photoheliograph to be seen

George Airy, early 1860s. Carte de visite by Cundall Downes & Co., 168 New Bond Street & 10 Bedford Place, Kensington (partly cleaned and cropped)

The boundaries of acceptable research

Airy’s duty as ‘Our Astronomical Observator’ as set out in the Warrant by which he was appointed was to apply himmself ‘with the most exact care and diligence to the rectifying of the tables of the motions of the heavens, and the places of the fixed stars, so as to find out the so much-desired longitude of places for the perfecting the art of navigation. By contrast, the duties of the Astronomer Royal for Scotland, (a post created in 1834 and also appointed by Royal Warrant), were much wider and were ‘… to apply himself with diligence and zeal … for the extension and improvement of Astronomy, Geography and Navigation and other branches of Science connected therewith’.

Sometimes regarded as autocratic and arrogant, Airy took a clear view about the Observatory’s remit, particularly in light of its routine responsibilities and the limited funding available from the public purse. The wider issue of public funding of science in Britain came to a head in the late 1860s as the new subject of astrophysics was starting to open up. At the heart of the debate, was whether the government should sponsor a series of national astrophysical observatories or whether such work should be left to the combined efforts of Greenwich and the contributions of enthusiastic and often wealthy individuals (as it had been in the past). Against this background, in 1870 the government set up a Royal Commission on Scientific Instruction and the Advancement of Science, chaired by William Cavendish the Seventh Duke of Devonshire. Often referred to as the Devonshire Commission, its findings were published in a number of reports between 1872 and 1875. Click here to read Airy’s evidence to the commission which was given in 1872.

While all this was going on, business was very much as usual back at Greenwich and new programmes of work were initiated that included the measurement of the heat radiating from stars (1869–70) together with spectroscopy and daily photography of the Sun under the auspices of a newly established Solar Department (1873).

The problem of the Observatory’s reach was one that clearly vexed Airy. By 1875, the Observatory had been in existence for 200 years and Airy in office for 40. He took the opportunity to publicly review both the achievements of the past together with the work that the Observatory might be involved in the future. He believed most strongly that the Observatory should not involve itself with the ‘new physical investigations’, and added that if in the future the Observatory programme should be cut, it should be in the areas of Meteorology, Photoheliography and Spectroscopy; ‘not as unimportant in themselves, nor as ill fitting to the work of the Observatory, but as the least connected to its original aims’. The views and approach of his successor, William Christie, turned our to be altogether rather different.

The origins of the photoheliographic programme at Greenwich

The scope of the Observatory’s work in Airy’s time

Other work undertaken by Airy

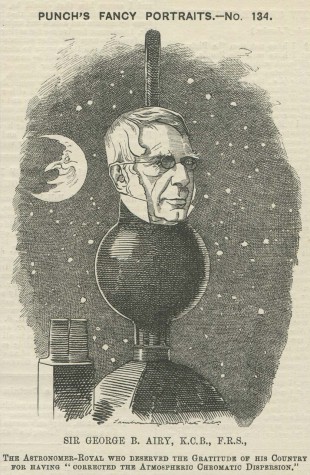

Punch and the Men of Mark

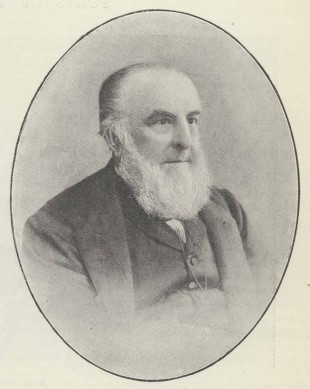

Each year from 1876 to 1883, Lock and Whitfield produced a volume of 36 ‘contemporary portraits of men distinguished in the senate, the church, in science, literature and art, the army, navy, law, medicine, etc’. Each portrait was an oval woodburytype and each volume had the title Men of Mark. Each photograph was accompanied by a brief biographical entry of 400-450 words written by Thompson Cooper, a journalist of The Times. Airy’s photo appeared in 1877 in Volume 2. An extract from the accompanying biographical note is reproduced below.

‘… In 1869 he communicated a remarkable discovery to the Royal Astronomical Society, in a “Note on Atmospheric Chromatic Dispersion, as affecting Telescopic Observation, and on the mode of correcting it.” He was created a K.C.B. in 1872. Sir G. B. Airy was intrusted with the entire direction of the British portion of the enterprise for observing the Transit of Venus in December, 1874; and lately he has suggested a new method of treating the Lunar Theory, the calculations for which are now in hand. …’

The reference to the paper on Atmospheric Chromatic Dispersion seems rather bizarre as it was not exactly one of Airy’s better known works, though it was relevant to those observing the Transit of Venus.

Sir George Biddell Airy. Woodburytype by Lock & Whitfield. From Men of Mark, Volume 2, London (1877)

A few years after Lock and Whitfield began publishing their volumes, the cartoonist Linley Sambourne began contributing ‘Fancy Portraits’ of contemporary personalities to the magazine Punch or the London Charivari. Published between 1880 and 1889, there were nearly 200 portraits in total. Fancy Portrait No. 134 was of Airy. Published on 5 May 1883, it depicts his body as the Greenwich Time Ball. Sambourne’s source of inspiration was Airy’s entry in Men of Mark. His face was copied directly from the photograph. The inclusion of the Moon was inspired by the reference to the Lunar Theory whilst the phrase “Atmospheric Chromatic Dispersion”' is lifted straight from the text. Given that Men of Mark had been published some five years or so earlier, it seems unlikely that many readers would have understood the allusions.

Resignation from the office of Astronomer Royal

In 1881, as he approached his 80th birthday, Airy took the decision to retire. The precise details on what prompted the decision of how this played out are difficult to discern. What follows is based on entries in his Journal (RGO6/27), the Minute and Letter books of the Board of Visitors (ADM190/3, 4 & 14) and his autobiography.

On 5 May Airy wrote to Lord Northbrook (First Lord of the Admiralty) ‘on resignation from Office’, receiving a reply a few days later on Monday 9 May. Copies of the letters have not been found, but it is assumed that this was an exploratory letter outlining his future intentions.

His actual resignation letters were submitted around a month later on Saturday 4 June – the day of the annual visitation. At the meeting of the Board, Airy ‘announced his intention of shortly retiring from his position at the Royal Observatory’. On the same day, (presumably after the meeting), he wrote to both Northbrook and the Prime Minister, William Gladstone announcing his desire to resign his post of Astronomer Royal on 15 August.

According to the minutes of the Board ‘the following resolution [reproduced below] proposed by Professor J. C. Adams, and seconded by Professor G. G. Stokes, was then unanimously adopted and ordered to be recorded in the Minutes of the Proceedings.’ It listed Airy’s many achievements and ran to over 500 words.

Surprisingly, the resolution as recorded in the rough minute book has only a couple of very minor crossings out. This implies either that the Board knew Airy was about to resign and had prepared a draft resolution for adoption, or that the fine detail of the resolution was fleshed out after the meeting and only then recorded in the minute book. The letter book (ADM190/14) confirms it was the latter. It contains a typed letter dated 11 June 1881 from William Spottiswoode (President of the Royal Society and Chairman of the Board) to the Board’s Secretary.

‘Dear Sir, Enclosed is the resolution, which I have this morning received from Professor Smith. He has made a few emend ions, of which I quite approve. I think that the Board left discretion [a fact not recorded in the minutes] to myself and Smith to make any such alterations as might seem desirable without altering the sense of the document.

I have a committee of the R.S. on Tuesday at 2.0.P.M. If it would suit you to meet me there at 1.45, I should be very glad to see you.’

The ‘enclosed resolution’ appears to be the original document drafted at the meeting as it contains the type of alterations that might be expected in a document that was drawn up on the fly. It also contained further alterations to the wording that were introduced by Smith.

Despite the fact that the wording of the resolution as recorded in the minutes was not that that was actually agreed at the meeting, the minutes were confirmed by the Board at their next meeting and signed off by the Chairman. The deceit seems rather ironic as Airy himself was a man of the utmost propriety.

The final text as recorded in the minutes was as follows:

‘The Board having heard from the Astronomer Royal that he proposes to terminate his connection with the Observatory on the 15th of August next, desire to record in the most emphatic manner their sense of the eminent services which he has rendered to Astronomy, to Navigation and the allied Sciences, throughout the long period of 45 years during which he has presided over the Royal Observatory.

They consider that during that time he has not only maintained but has greatly extended the ancient reputation of the Institution, and they believe that the Astronomical and other work which has been carried on in it under his direction will form an enduring monument of his Scientific insight and his powers of organization.

Among his many services to Science, the following are a few which they desire especially to commemorate:

(a) The complete re-organization of the Equipment of the Observatory.

(b) The designing of instruments of exceptional stability and delicacy suitable for the increased accuracy of observation demanded by the advance of Astronomy.

(c) The extension of the means of making observations of the Moon in such portions of her orbit as are not accessible to the Transit Circle.

(d) The investigation of the effect of the iron of ships upon compasses and the correction of the errors thence arising.

(e) The Establishment at the Observatory and elsewhere of a System of Time Signals since extensively developed by the Government.

The Board feel it their duty to add that Sir George Airy has at all times devoted himself in the most unsparing manner to the business of the Observatory, and has watched over its interests with an assiduity inspired by the strongest personal attachment to the Institution. He has availed himself zealously of every scientific discovery and invention which was in his judgment capable of adaptation to the work of the Observatory; and the long series of his annual reports to the Board of Visitors furnish abundant evidence, if such were needed, of the soundness of his judgment in the appreciation of suggested changes, and of his readiness to introduce improvements when the proper time arrived. While maintaining the most remarkable punctuality in the reduction and publication of the observations made under his own superintendance, he had reduced, collected, and thus rendered available for use by astronomers, the Lunar and Planetary Observations of his predecessors. Nor can it be forgotten that, notwithstanding his absorbing occupations, his advice and assistance have always been at the disposal of Astronomers for any work of importance.

To refer in detail to his labours in departments of Science not directly connected with the Royal Observatory may seem to lie beyond the province of the Board. But it cannot be improper to state that its members are not unacquainted with the high estimation in which his contributions to the Theory of Tides, to the undulatory theory of Light, and to various abstract branches of Mathematics are held by men of Science throughout the world.

In conclusion the Board would express their earnest hope, that in his retirement Sir George Airy may enjoy health and strength and that leisure for which he has often expressed a desire to enable him not only to complete the numerical Lunar Theory on which he has been engaged for some years past, but also to advance Astronomical Science in other directions.’

The substance of the resoltion was outlined to Airy by a member of the Board after the meeting and a copy of the resolution as minuted sent to him on 28 June by Robert Hall, the Naval Secretary of the Admiralty.

Retirement to The White House and appointment to the Board

Having decided to retire, (according to his autobiography) Airy ‘was engaged on the subject of a house for his future residence, and finally [date unknown] took a lease of The White House at the top of Crooms Hill, just outside one of the gates of Greenwich Park’. There are several mentions of the move to The White House in Airy’s Journal, the earliest of which is dated 22 June. Many concern the transfer of his books.

The White House in December 2007. The doorstep by the front door has a line cut into it showing the direction of the local meridian

Although Airy handed over to his successor William Christie on 15 August, he slept at the Observatory that night and moved to The White House the next day with his two unmarried daughters. According to his autobiography, he later bought the house at auction on 24 May 1889 after the owners put it up for sale. It stayed in the family until at least 1920 when Wilfred Airy died.

Airy’s direct involvement with the Observatory did not end with his retirement. He joined the Board of Visitors in 1883 at the behest of William Spottiswode on the death of Professor Smith. His date of appointment was 27 March (ADM190/15). He attended every Visitation from then until his death in early 1892. Given that he was first appointed to the Board in 1831, his involvement with the Board spanned a remarkable period of 60 years with a gap of just one year in 1882. Of the 59 years that he was directly involved, 14 were as a member of the Board and 45 as Astronomer Royal in attendance.

Death and subsequent burial at Playford

Playford Church in about 1905. Airy's grave is visible behind the railings on the right. Postcard by Smiths

Click here to see more images of the graves, the Airy family plot at Playford and the two near identical memorials that were subsequently erected inside the Church and at St Alphage’s in Greenwich.

Siblings

Of Airy’s sister Elizabeth we know very little beyond the fact that she remained unmarried, lived with her parents and often went of holiday with Airy. Born 1803. Died 1879.

Airy’s brother William was six years younger than him. Born 1807. Bury School 1820-1825. Admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge as a sizar at the age of 18 in February 1825. B.A. 1829, M.A. 1832. Ordained Deacon Norwich June 1930, Rector of Bradfield St.Clare, Suffolk 1833-1836. Married 1834. Vicar of Keysoe, Bedfordshire (a living in the gift of Trinity College Cambridge) 1836-74. Rural Dean of the Deanery of Eton, Bedfordshire 1839. Rector of Swineshead, Huntingdonshire 1845-1874. Domestic Chaplain to Duke of Manchester. Died 1874. Buried Keysoe. Made a few observations with the Transit Instrument at the Cambridge Observatory in the Spring of 1828 which were included in the volume of published observations.

Airy’s brother Arthur died in infancy. Born 1809. Died 1811

Obituaries

The three obituaries below were written by three very different people. Edward Routh, fellow of the Royal Society and a leading Cambridge mathematician married Airy’s daughter, Hilda, in 1864. Edwin Dunkin joined the Observatory staff in 1838, rising to the rank of Chief Assistant on Airy’s retirement before himself retiring in 1884. His post of Chief Assistant was filled by the third obituarist Herbert Turner, who at the time of writing was about to be elected as one of the two new Secretaries of the Royal Astronomical Society. The other Secretary elected was Walter Maunder, who was appointed to the Observatory staff in 1873 and had had a somewhat strained relationship with Airy.

Obituary by Edward Routh. Proceedings of the Royal Society, 51 (1892), i–xii.

Obituary by Edwin Dunkin. The Observatory, Vol. 15, p. 74–94 (1892)

Obituary by Herbert Hall Turner. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 52, p.212–229 (1892)

Further Reading

The Excise from The whole law relative to the duty and office of a Justice of the Peace. Thomas Williams (1794)

Town maps and plans of Alnwick 1610–1910

The Airy Plaque unveiled (the origins of the blue plaque at Alnwick). North Eastern Branch of the Institute of Physics Newsletter. Issue 9 (March 2004)

Punch’s Fancy Portraits: A Handlist compiled by Ged Martin

John Herschel Correspondence relating to the posts of Astronomer Royal

Calculation and Tabulation in the Nineteenth Century: Airy versus Babbage. Doron David Swade. (Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD University College London, 2003 pdf)

George Biddell Airy, F. R. S. (1801-1892): A centenary commemoration. Allan Chapman, Royal Society Notes & Records, Volume 46, issue 1 (January 1992)

Airy's Greenwich staff. Allan Chapman, Antiquarian Astronomer, 2012, Issue 6, p. 4-18

A National Observatory Transformed: Greenwich in the Nineteenth Century. Robert Smith, Journal for the History of Astronomy, Vol.22, NO. 1/FEB, P. 5, 1991

Image licensing information

The image of the Blue Plaque in Alnwick is Reproduced under the terms of an Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0) licence courtesy of Peter Reed. It has been cropped and reduced in size for use here. The original image was downloaded from flickr. Download orginal image here.

The following inages are reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence courtesy of the University of Cambridge, Institute of Astronomy Library.

Lithograph of George Airy by Isaac Ware Slater, after Thomas Charles Wageman. Download original image here. The date of 1833 is taken from Airy’s autobiography p.102.

Engraving of Northumberland Equatorial by J. Basire (1844). Download original image here.

The following images are © National Portrait Gallery, London and are reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence.

Portrait of Thomas Clarkson by Charles Turner, after Alfred Edward Chalonare (Object ID: NPG D33313).

Albumen print of Hubert and Wilfrid Airy by W. Nichols (Object ID: NPGx1221)

The Drawing by Elizabeth Smith is reproduced reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library. The black border has been cropped. The image is reduced in size and are more compressed than the original. Download original image here.

The photograph of Richarda Airy (Object Number: 1977-541/9) is reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) courtesy of The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum. It has been cropped and resized for this website.

The painting of the South Dome by Henrietta Smythe are reproduced by kind permission of The Scout Association Heritage Collection. Henrietta Grace Smythe (1824–1914) was the sixth of eleven children born to Captain (later Admiral) William Henry Smythe (1788–1865), a distinguished astronomer, fellow of the Royal Society and a member of the Observatory’s Board of Visitors from 1836 until his death. One of Henrietta’s two older brothers, Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819-1900), became Astronomer Royal for Scotland in 1846. The other, Warrington Wilkinson Smythe (1817–90), married Anna Storey Maskelyne, granddaughter of the fifth Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne. In 1846, Henrietta married Baden Powell, the Savilian Professor of Geometry at Oxford who was 28 years her senior and previously twice married. Widowed in 1860 shortly after the birth of her tenth child, she changed the family name to Baden-Powell. Her son Robert was the founder of the Scout Movement.

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan