…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

The Magnetic Observatory at Greenwich

Although magnetic observations had been sporadically made since Flamsteed’s time, it wasn’t until 1817 that a permanent observatory was set up at Greenwich. The Magnetic Observatory moved to Abinger in Surrey in the early 1920s due to potential interference from the nearby railways which were about to be electrified. It was operational there from 1924 until 1957 when it moved to Hartland in Devon.

Pond’s Magnetic Observatory (1817-1824)

In 1816, the Admiralty asked the Astronomer Royal, John Pond, to make regular observations of magnetic variation (declination). A Magnetic House was put up during April and May 1817 (RGO6/1/54), and observations commenced in 1818. Airy records in his published plans (1847 & 1863) that it was built in the Lower Garden. This was enclosed from the park in two stages, the northern half in 1814, and the southern in 1837. It consisted of a deep semicircular hollow in the hillside with a more or less level bottom. In 1817, the level part was in use as a kitchen garden and it was perhaps for this reason, that Pond made the unwise decision to place the observatory on the east side on the slope of the hill. The foundations rapidly gave way, causing the building to become so dangerous, that the instruments were removed. It was demolished in 1824 and magnetic observations ceased until a new observatory was established by Airy in 1838.

An international Collaboration

In 1829, a project for the simultaneous observation of magnetic declination on about six pre-selected days each year at about 20 sites across Europe and the Russian Empire was initiated by Alexander von Humboldt in collaboration with Carl Gauss. The aim was to determine the extent and simultaneity of the disturbances.

Humboldt used the lobbying power of the Royal Society (who asked the recently appointed Astronomer Royal George Airy to advise), to help get the work extend across the British Empire. Humboldt kick-started the process in April 1836 with an open letter to the President of the Society (The Duke of Sussex) on the subject of ‘The advancement of the knowledge of Terrestrial Magnetism, by the establishment of magnetic stations and corresponding observations’ (click here to read the letter).

Meanwhile, the Observatory’s Board of Visitors, had been reformed in 1830 and now had Airy, in his capacity as Plumian Professor at Cambridge, together with George Peacock, John Lubbock, Francis Baily, Davies Gilbert, John Herschel and Francis Beaufort amongst its members (Click here for a full list). At their meeting on 13 June 1831, the Visitors resolved ‘that it is highly desirable that a series of magnetical observations should be carried on at the Observatory’ (ADM190/4/67). A similar resolution was also passed regarding Meteorological Observations.

By the end of 1834, neither these, nor some of the other resolutions passed by the Visitors since 1831 had been acted upon. For reasons still to be explained, on 23 February 1835, the Duke of Sussex, in his role as chairman of the Visitors, arranged for the resolutions to be forwarded (with other extracts from the minutes) to the First Lord of the Admiralty, Earl de Grey (who had been appointed by the new Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel on 22 December 1834) (ADM190/7/10). At their meeting on 6 June 1835, (by which time the Peel government had fallen and de Grey replaced), the Visitors were informed that the proposals for the Observatory to make Magnetic and Meteorological observations had been favourably received by the Admiralty, who hoped that no unnecessary delay would be allowed to take place in carrying the proposal into effect. As a result, the Visitors set up a sub-committee (Davies Gilbert, Baily, Peacock and Lubbock) with the powers to call on external assistance from others, (including Forbes, Robinson Daniel and Whewell), to suggest ‘the best mode’ of carrying them out (ADM190/4/94).

It is not know if the committee was ever convened. Over a year earlier however, in May 1834, the process of installing Airy as Astronomer Royal had begun. When he took over from Pond on 1 October 1835, he rapidly introduced a number of reforms. On 4 January 1836, he met with Samuel Christie at the Observatory to get his view on a possible location for a magnetic observatory (RGO6/24) and on 12 January, he wrote to Charles Wood (Secretary to the Admiralty) laying a specific proposal before him, in which he suggested that the estimated cost of building and equipping a magnetic observatory would be £578 (£300 for the building, £258 for equipment and £20 for preliminary experiments). He also suggested that the sum of £600 should be allowed in the Navy Estimates for building it (ADM190/4/97). The letter was referred by Wood to the Visitors who discussed it at a special meeting that was held at Kensington Palace on 26 February. At the meeting, it was resolved ‘that the required steps be taken for carrying it into execution without delay’ (ADM190/4/97). To the irritation of Airy, the meeting was held too late for the amount to be included in the estimates for the year 1836/7. The existing Observatory site was cramped, and Airy’s proposal to carve out a site from the the Drying Ground and Middle Garden (now both part of the Meridian Garden), was rejected by the Visitors (RGO6/45/9-11). Instead, it was decided to seek to enclose more ground from the Park.

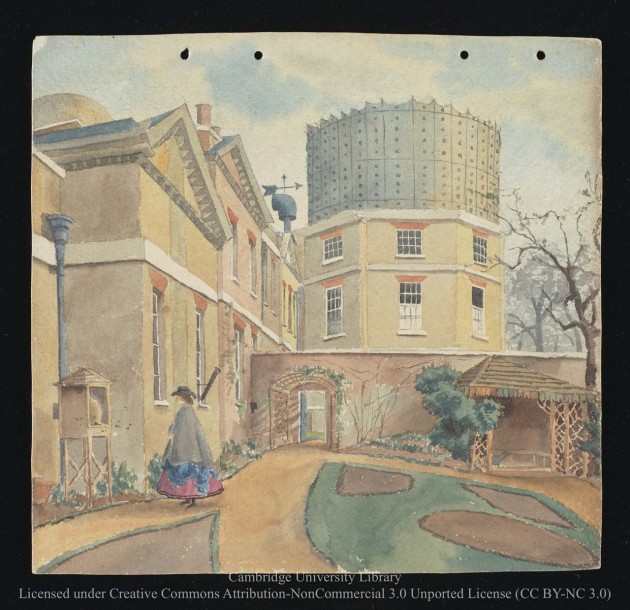

Looking eastwards from the Middle Garden towards the recently completed Great Equatorial Building. The archway led through to the Drying Ground. The summerhouse on the right occupies the western end of the site originally selected by Airy for his Magnetic Observatory. Watercolour painting by Chritstabel Airy, March 1863. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

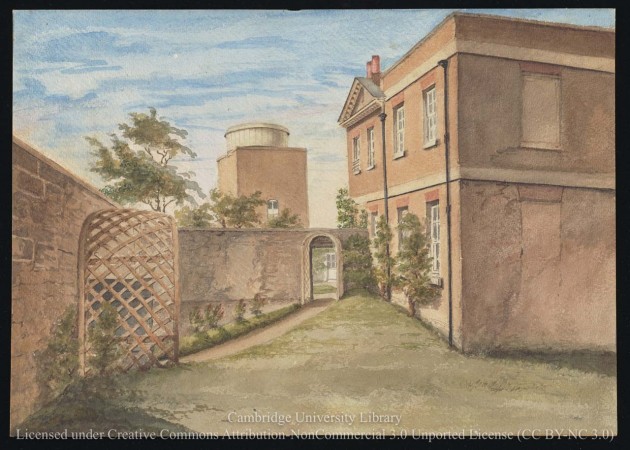

Looking westwards from the Drying Ground back through the archway towards the Middle Garden. Had the Magnetic Observatory been built as originally proposed, two thirds of it would have been in the Drying Ground (to the left of the path) and one third in the Middle Garden. The building would have bridged over the site of Flamsteed's Well Telescope whose position (beneath the part of the wall that would have had to have been demolished) was unknown to Airy at the time. Watercolour painting, probably by Airy's daughter Christabel, 10 July 1847. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

By June 1836, Airy was in correspondence with the Commissioner of Woods and Forests to secure the extra land he required. The 1837/8 estimates included an amount of £566 for ‘fencing the ground, and erecting a building for magnetic observations’. An extension of the site southwards was fenced off in the spring between 26 April and 13 May 1837 (Work 16/126 & Airy autobiog.). Bounded to the east by Blackheath Avenue in the Park, this new enclosure had the additional advantage for Airy of both extending and increasing the privacy of the Lower Garden, which up until then had always been overlooked. In the meantime, Airy borrowed the Magnetic House belonging to Captain Fitzroy (presumably to carry out various tests). This was initially set up in the Courtyard on 9 November 1836, but moved to the new Magnetic Enclosure on 16 May just three days after its fencing off had been completed (RGO6/24).

Airy’s Magnetic Observatory of 1838

The new building, which was begun in 1837, was completed in May 1838. It was erected where the Peter Harrison Planetarium now stands and was constructed under the supervision of George Leadwell Taylor (1788-1873), the Civil Architect of the Admiralty (plans in RGO/6/44/97–8). It was originally to be built of concrete, but after numerous experiments on various kinds, it was decided instead to build of wood on a concrete foundation – all iron and brick (which normally has residual magnetism) being excluded.

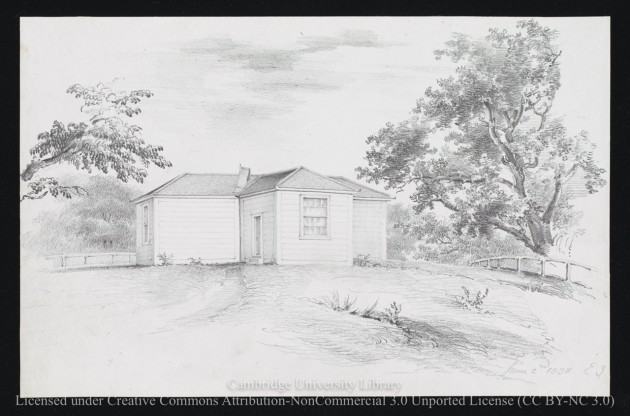

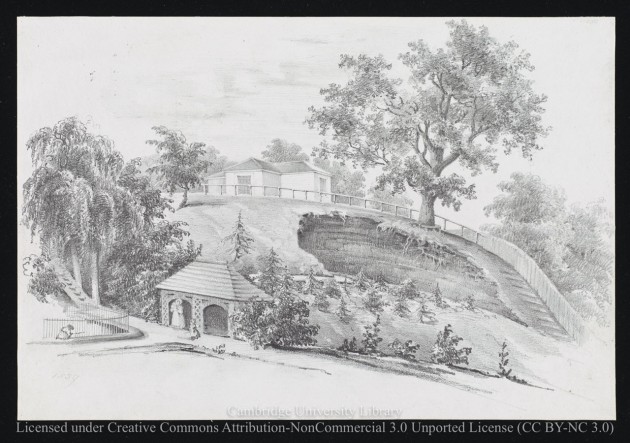

The newly completed Magnetic Observatory from the north-east. The roof shutter, though which transit observations of certain circumpolar stars could be made, can be seen on the roof of the east wing (left) close to its junction with the roof of the north wing. Its position is marked on the 1844 plan plan below. Pencil drawing dated 2 June 1838 by Airy's sister-in-law, Elizabeth Smith. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

In the 1839 volume of Greenwich Observations, Airy described the dimensions and orientation of the building as follows:

‘Its form is that of a cross with four equal arms, nearly in the direction of the cardinal magnetic points: the length within the walls, from the extremity of one arm of the cross to the extremity of the opposite arm, is forty feet: the breadth of each arm is twelve feet. The height of the walls inside is ten feet, and the ceiling of the room is about two feet higher.’

Click here to read the complete description of the building and the arrangement of instruments within it.

As originally envisaged, the observing programme was restricted in its scope to observations being made (in conjunction with other magnetic observatories around the world) on just four 24 hour periods in 1839 and four in 1840, and for this, the Admiralty made no provision for extra staffing. In 1839, the position of the free Meridional Magnet was in fact observed every five minutes throughout the day on eight days: 22 & 23 February, 24 & 25 May, 30 & 31 August and 29 & 30 November.

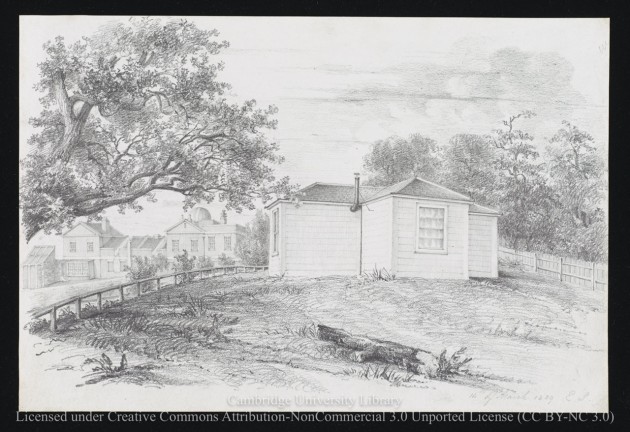

The Magnetic Observatory from the south-west with the main Observatory buildings behind. Pencil drawing dated 14 March 1839 by Elizabeth Smith. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

The Magnetic Observatory from the north-west with the Lower Garden in the foreground. The site of Pond's Observatory was on the slopes at the top of the steps that can be seen above the fenced pond on the left. Pencil drawing dated 1839 by Elizabeth Smith. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

Expansion to become a Magnetic and Meteorological Observatory

In 1839, James Clark Ross was appointed to command a British Naval Expedition to conduct a series of magnetic observations in the southern hemisphere and to locate and reach the South Magnetic Pole if possible. On 18 June 1940, Lubbock reported from the Committee of Physics of the Royal Society to its Council in favour of the construction of a magnetic and meteorological observatory near London to make parallel observations. After correspondence with Sheepshanks, Lord Northampton, and Herschel, Airy wrote to the Council on 9 July, pointing out what the Admiralty had done at Greenwich, and offering to cooperate. In a letter to Lord Minto, (who had replaced Baron Auckland who himself had replaced Earl de Grey as First Lord of the Admiralty), Airy made the case for the work to be done at Greenwich where the cost of doing it would be much less than establishing a new observatory elsewhere. On 11 August, the Treasury assented to the work being done at Greenwich, limiting its funding to the duration of Ross’s voyage. As a result, a temporary Magnetical and Meteorological Department was established with observations being made on a daily basis. James Glaisher was put in charge as Superintendent and two additional assistants employed on a non established basis (Edwin Dunkin, and John Russell Hind). Most of the contemplated observations were begun before the end of 1840: ‘as much as possible in conformity with the Royal Society’s plan’.

In his report to the Board of Visitors in June 1841, Airy stated that:

‘A small wooden house, the property of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N., which was carried by him, in the Beagle, in his circumnavigation of the globe, has been planted in the southern part of the Magnetic Ground for observations of the dipping-needle, and any other observations which would be prejudiced by the action of the large magnets in the Magnetic Observatory.’

This was presumably the same hut that had been erected in the Magnetic Ground, in 1836.

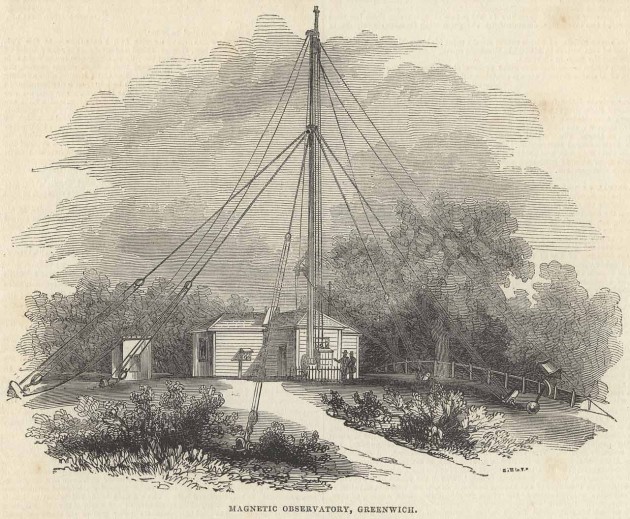

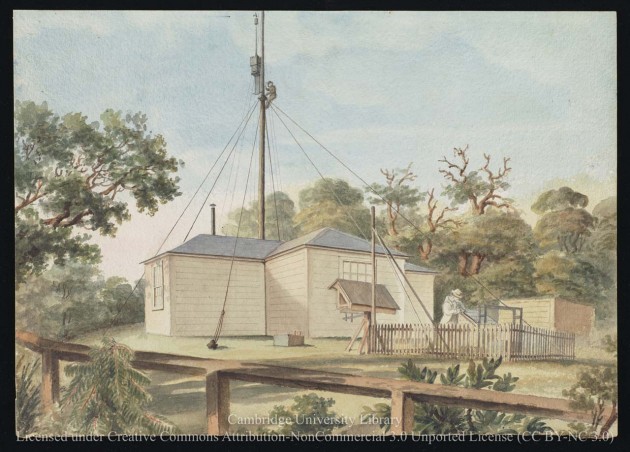

One of the most striking features of the building, the electrometer mast, which was removed 1879/80. It towered high above the building and was used for inductive experiments. According to Airy’s Journal (RGO6/24), it was erected on 19 July 1841. In his autobiography however it is incorrectly stated that it was erected in 1844. Many of the meterological instruments were placed on the lawn to the south of the Pavilion. The barometer was in the Pavillion itself, whilst two anemometers were placed on the roof of Flamsteed House (Osler’s erected in 1839/40 and Whewell’s erected 1843 but replaced with one by Robinson in 1862).

The Magnetic Observatory from the north-east in 1844. The pole in front of the building is the electrometer mast which stood 80 feet high. The small hut to the left contained the dip circle. From The Illustrated London News, 16 March 1844

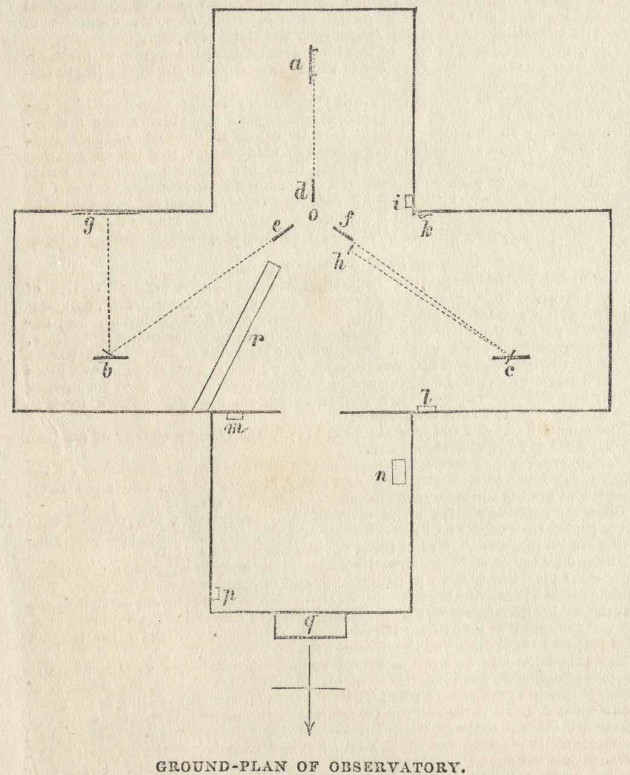

Ground plan of the Magnetic Observatory in 1844. In the plan: a, shows the position of the Declination Magnet in the southern arm of the Cross. b, the Horizontal Force Magnet in the eastern arm of the Cross. c, the Vertical Force Magnet in the western arm of the Cross. d, e, f, the three Telescopes, by means of which the variations of the position of the magnets was observed. o, the place of the Observer. g, the scale of the Horizontal Force Magnet. h, the scale of the Vertical Force Magnet. i, the Mean-time Clock. k, the Barometer. l, the Sidereal Clock. m, the Check Clock in the Ante-room. n, the Fire-grate. p, the Alarum Clock. q, the projecting North window, containing the Electrical Instruments. r, the opening in the roof in the Astronomical Meridian. From The Illustrated London News, 16 March 1844

Click here to read the complete 1844 article from The Illustrated London News.

Funding from the Treasury rather than the Admiralty

When the new programme of work was sanctioned it was funded directly by the Treasury rather than by the Admiralty. In 1842, it was determined that the programme should be extended and a further three years. This period expired in December 1845, and upon urgent representation of the Geographical Society, the Treasury again consented to extend the time. In 1842, Airy pointed out to the Admiralty the inconvenience of furnishing separate estimates to both them and the Treasury – a point he was to make several times, including in 1846 when he proposed that the whole of the cost of the Observatory should be borne on the Navy Estimates – pointing out that ‘the whole Estimates and Accounts of the Observatory never appeared in one public paper’. He was rebuffed. The charge was eventually transferred to the Admiralty but only when there was a wholesale transfer of this and other publically funded scientific activity from the Treasury accounts to those of the Army and Navy in the year 1868/9. It took until 1884 before the Magnetic Assistant to be employed on the same terms and conditions as the Astronomical ones. Although the Magnetical and Meteorological Department was only originally intended to be temporary, it stayed in existence until 1960/61 when meteorological observations ceased.

Alterations to the Magnetic Building and the erection of the Magnetic Offices

In 1846, a porch was added to the main building. On 23 April 1853 there was a small outbreak of fire which fortunately ‘did little mischief’.

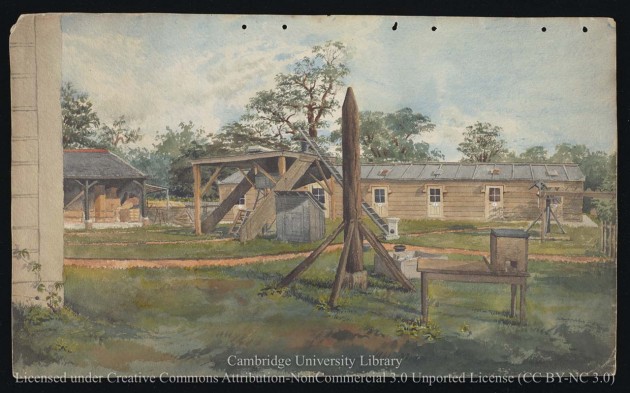

In this second view from the south-west, the revolving wooden thermometer stand which was erected in 1846 can be seen in front of the south window. It carried the dry and wet thermometers, dew point apparatus etc. The fenced area to its right was a small enclosure for radiation experiments etc. The man behind it, is standing by the wooden structure where the ground thermometers were housed. Watercolour painting, unknown artist, 17 July 1847. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

In 1862, the building was extended northwards and the former Dip House and Deflexion House, were taken down as they were in the way of a range of seven wooden rooms (usually referred to as offices) that were about to be built running parallel to the southern boundary. Of these, the most easterly (office 1) was used as an experiment-room, whilst the most westerly (office 7) contained the Deflexion-apparatus and the Dip-Instrument. The remainder were appropriated to various operations of photography – photographic registration having been first introduced in 1847, in what was one of the earliest scientific uses of photography. On the south side of the range, at a small distance, there was a long desk that was used for making contact prints from the photographic plates, which in those days, still required a lengthy exposure in daylight. Beyond this a piece of ground a few feet in breadth was left vacant. In 1872/3 when the Observatory obtained its first photoheliograph for solar observation a small building with a rotatory dome was erected on the south side of and communicating with Magnetic Office 3, Magnetic Office 2 being altered for use as a Chemical Room.

By the time this later view was painted, the fenced experimental enclosure had been relocated to the west (left). This has allowed the wooden structure around the ground thermometers to be seen more clearly. The large pipe with the cowl protruding from the roof of the Pavilion ran down to the building's basement and is a ventilation tube that was installed in 1866/7 in an attempt to allow greater control over the temperature there. The ladder on the right is leaning against a flat roofed square shed with adjustable sunscreens which was open on all four sides, in which a rotating vertical barrel for the photographic registration of wet and dry bulb thermometers was located. This was erected in 1846/7. In 1884/5, it was replaced with a new shed for the new set of photographic, thermometers. Watercolour painting by Christabel Airy, 18 June 1868. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

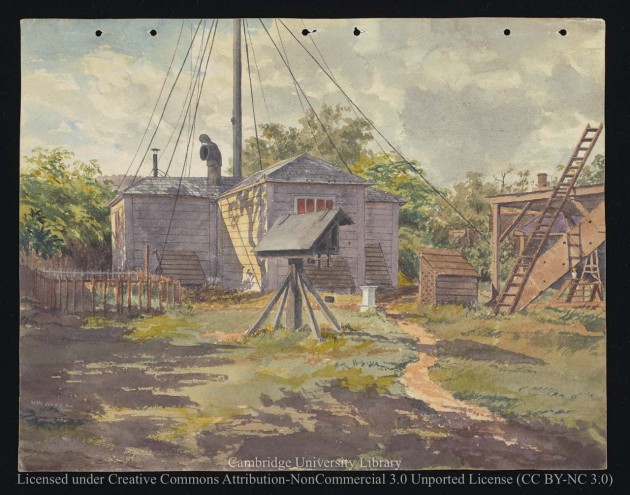

In this south facing view from 1863, a tiny corner of the Magnetic Pavilion can be seen on the left. It was during 1863 that the revolving wooden thermometer stand was relocated to the south (it can be seen in its new location on the right). The post that had formerly supported the revolving part was still present when the picture was painted and dominates the centre of the view. Behind it, the row of seven magnetic offices (which are numbered from left to right) can be seen. The open sided building with the slate roof containing wooden crates (left), is the Great Shed. It was erected in 1851/2, but dismantled and moved to a different location in 1869 following a southward extension of the Observatory grounds. Watercolour painting by Christabel Airy. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

In pursuit of a stable temperature

Further changes were made in 1864, when a basement to the Magnet House was excavated in an attempt to provide an environment with a more stable temperature. Its walls were made of specially selected bricks, which were almost free of magnetism. As it had one of the most stable temperatures in the Observatory it was where Airy choose to mount the Observatory’s new sidereal standard clock (Dent No. 1906) in 1871 (it was mounted on the north wall).

The deep ground thermometers of the Meteorological Observatory had already shown that not too far below the surface, the ground temperature is extremely stable. Christie took further advantage of this when a drain was being laid for a new sink in the basement. He explained what had been done in his 1886 report to the visitors:

‘A line of 9-inch pipes about 155 feet in length has been laid underground for the ventilation of the Magnet basement, the depth below the surface varying from 5 feet at the lower end in the South Ground to 11 feet 6 inches at the entrance to the basement. Thus the air which is admitted (by means of two branch pipes) into the east and west arms of the basement is warmed in winter and cooled in summer by passage through a considerable extent of soil at nearly constant temperature.’

What Christie had built was an early form of heat pump. Interestingly, it was Lord Kelvin, a member of the Board of Visitors and later its chairman, who developed the theory of the heat pump – something he is said to have done by 1852. Rather regrettably, those responsible for the archaeological survey that took place while the excavations for the new planetarium were being carried out in 2004, were poorly briefed and had not done their homework. They were unaware of the pipes, which were duly bulldozed without being recorded – or probably even noticed. A similar fate awaited the bricks of the basement. Their presence was noted, but none were taken away to test just how magnetic they were. Nor was any attempt made to establish where on the north wall the sidereal standard had been mounted.

Magnetic interference from later buildings

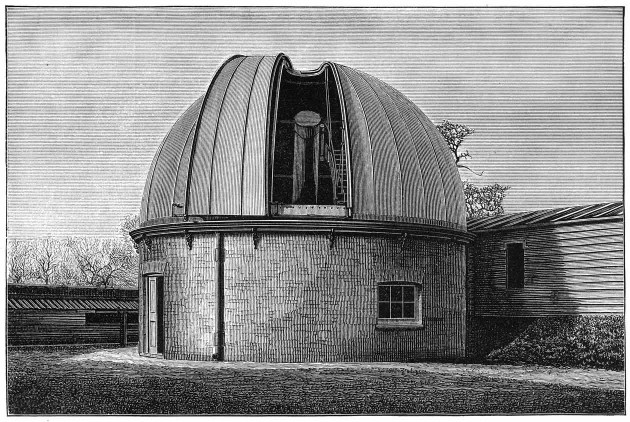

When the Lassell Dome was built in 1883, it was erected immediately to the south of, and connecting to Magnetic Office 7, in which the dip and deflexion instruments were located. These instruments were moved to the new library. The new dome and telescope contained copious amounts of iron, whose effects on the magnetic instruments were much exacerbated when construction of the South Building with its steel frame began in 1891. The building of the Altazimuth Pavilion nearby in 1894-5 exacerbated the problem further. Although Christie had hoped otherwise, it was soon apparent that certain of the magnetic instruments would need to be moved to a new location. When construction of the north wing of the South Building began at the end of 1894, the Magnetic Offices and the Lassell Dome had to be removed. Rather than demolish them, the Offices were literally picked up, turned through 90° and dumped near the western boundary in such a way that Magnetic Office number 7 which had been the most westerly, was now the most northerly. The Dome on the other hand was dismantled and reused on the top of the South Building,

The Lassell Telescope and Dome. The Magnetic Offices to which the Dome was attached are on the right. From: A Handbook of Descriptive and Practical Astronomy, Volume 2, Fourth Edition (London 1890) by George F Chambers

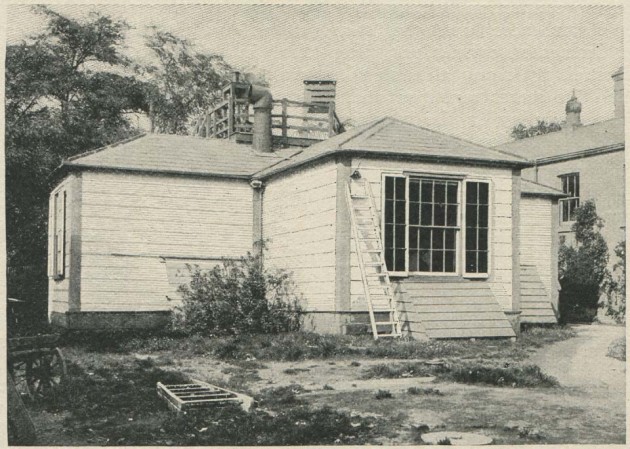

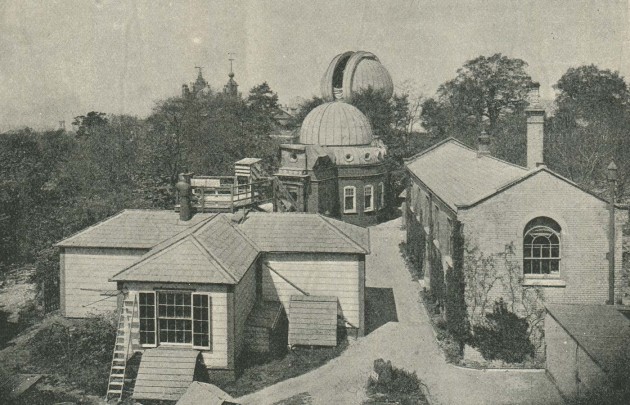

The Magnetic Observatory from the south in about 1896. The platform on the roof was added in 1872 for the observation of meteors, auroras, etc; the installation being completed in time for the August shower. Photograph by Cedric Davies, who worked in the magnetic department from 1895 until 1899. From an article by Maunder published in the May 1905 volume of Harper's Monthly Magazine. The image was previously used by Maunder in the Leisure Hour in 1898

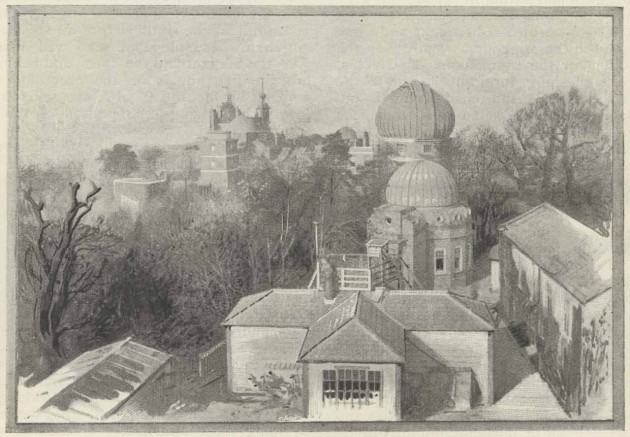

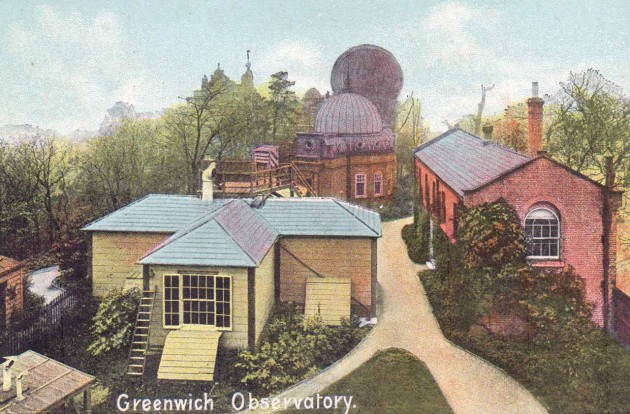

The Magnetic Pavilion with the newly completed Altazimuth Pavilion behind it and the 'New Library' to its right. Photo by the London Stereoscopic Company. From Pearson's Magazine (1896)

In this slightly later view from a higher viewpoint, more of the background buildings are visible as well as the Magnetic Offices in their new position. From The Leisure Hour (1898)

In this view from around 1905, the photographic thermometer house can also be seen (bottom left). From a postcard published by Shurey's Publications

Relocating across the Park

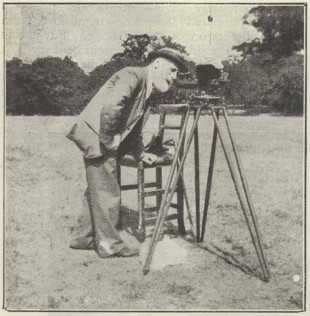

William Nash at work testing a possible new site for the Magnetic Observatory in Greenwich Park. From The Leisure Hour (1898)

In March 1914, a second building was completed to house a set of modern magnetic instruments. Constructed by the Works Department of the Admiralty, it consisted of a thickly-walled outer room containing an inner room, well insulated by a considerable air-space. To maintain the constancy of the temperature, electric heaters, controlled by a thermostat, were installed. It was known as the Magnetograph Building.

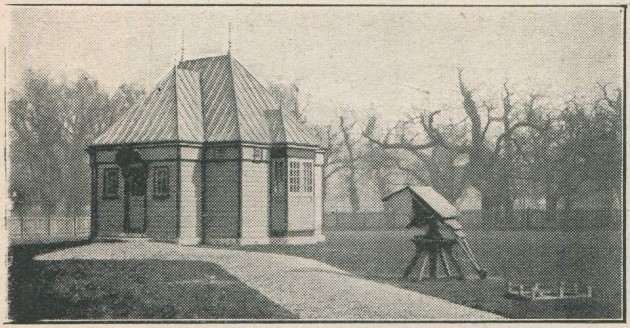

The new Magnetic Pavilion prior to the 31 March 1900. The entry door (left) was on the west side. The path to it came from the entrance to the Enclosure which was in its south-west corner. To the left of the path, a rain gauge can be seen in the grass. To the right, there is a protective enclosure housing some of the thermometers. Photo by Thankfull Sturdee. From Black and White Budget (23 March 1901)

The new Magnetic Pavilion. The entry door (left) was on the west side. The path to it came from the entrance to the This slightly later view also shows the Stevenson Screen erected on 31 March 1900. Photo by Charles Craven Lacey. From Maunder's Royal Observatory Greenwich (1900)

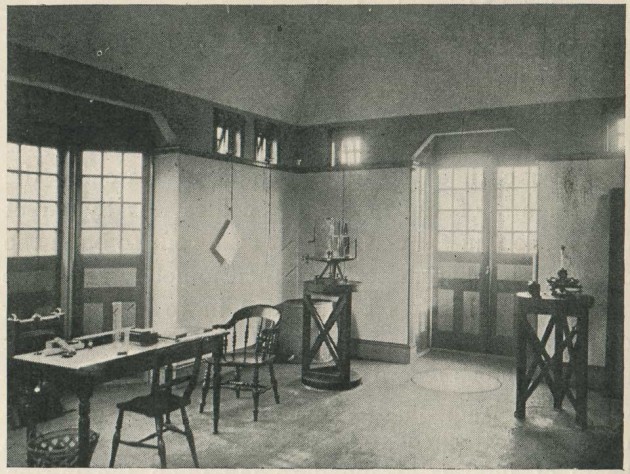

The interior of the new Magnetic Pavilion. Photo by Charles Craven Lacey. From Maunder's Royal Observatory Greenwich (1900)

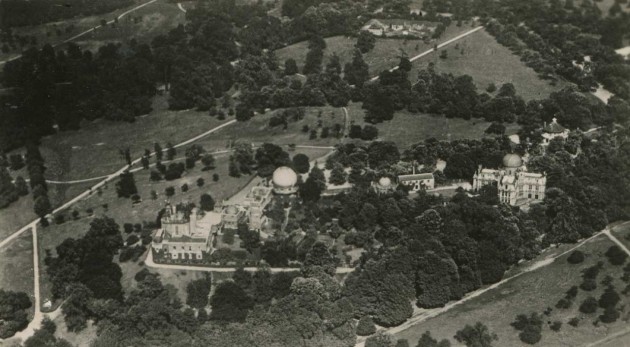

The Christie Enclosure containing the Magnetic Pavilion (centre) and Magnetograph House (left) can be seen at the top of this aerial photo, with the main Observatory site below. The absence of the old Magnetic Pavilion on the main site and the absence of other buildings in the Christie enclosure indicates that the photograph was taken between 1919 & 1932. From a postcard published by Central Aerophoto Co. Ltd. (No.2615)

A new use for the buildings on the main site

Meanwhile, back on the main site, the relocated Magnetic Offices were used initially as regular offices. Following the completion of the South Building, they were no longer required for this purpose. The Navy Estimates for the year 1898–99 show that Christie asked for £75 to convert four of the seven offices into two loose boxes, a harness room and a coach house in order to provide stabling for visitors as the nearest otherwise available was nearly a mile away (RGO7/51). The earliest reference to them being used as such, seems to be the site plan dating from around 1905.

With the outbreak of war in 1914, Dyson had a range-finder fitted onto the roof of the old Magnetic Building. The building was demolished in 1918, some of its parts being reused to construct a small hut in the Christie Enclosure for the electrometer, which was transferred at this time.

Interference from the railways and the move to Abinger

As early as 1890, interference began to be detected from the South London Electric railway some 4½ miles away. By 1893, a clause had been agreed for insertion in future parliamentary railway or tramway bills authorising electrical power, in order to protect the magnetic observatories at Greenwich and Kew (established in 1857) along with various other government scientific establishments in London. As time went on and more train and tram lines became electrified the problem was kept under control. The First World War came and went and was followed by a rationalisation of the railways and with it a greater degree of standardisation. To this end the Ministry of Transport set up an ‘Electrification of Railways Advisory Committee’ chaired by Sir Alexander Kennedy. The outlook for the Magnetic Observatory at Greenwich soon began to look bleak, so much so, that on 5 October 1921, a conference was convened at the request of the Admiralty to discuss the desirability & practicalities of relocating the magnetic observatory. A site at Abinger Bottom near Leith Hill, some 26 miles distant from Greenwich, was formally acquired in February 1924. Absolute observations began on 24 March, with the site becoming fully operational on 1 April 1925. Meanwhile, back near Greenwich, the first electric trains began to run on 28 February 1926 with a full service from 6 June. At this point, all regular observations at Greenwich with the absolute magnetic instruments ceased. More about the events leading up to the move away from Greenwich can be read in the section on Abinger.

Demolition of the remaining buildings at Greenwich

By the 1940s, the former Magnetic Offices were in use as follows Offices 1 & 2 (the most southerly) as garages, Office 3 as an empty case store, Office 4 as a paint store and offices 5 to 7 as stables. They were badly damaged by blast in the Second World War and were demolished some time around 1959/60. Back in the Christie Enclosure, the New Magnetic Pavilion was demolished in 1934 and the Magnetograph Building became known as the Meteorological Recording Building. It was demolished in 1959 when the Enclosure was cleared of buildings and returned to the Park.

Other Links

Click here to read Christie’s 1909 description of the Buildings and Instruments of the Magnetical and Meteorological Observatory.

Image licensing information

The images reproduced courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library have been reduced in size and are more compressed than the originals and have been reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. Links to the individual images are as follows: image 1, image 2, image 3, image 4, image 5, image 6, image 7, image 8.

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan