…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

The Courtyard

By the 1940s, the Observatory’s main site at Greenwich occupied an area of 2.46 acres.This section of the website deals only with the courtyard. It is bounded by Flamsteed House to the west, the Meridian Building to the south, the gates from the Park to the east and railings to the north.

Other parts of the grounds are covered in the following sections:

The Astronomers’ Garden

The Meridian Garden

The Garden to the west of Flamsteed House

The Magnetic and South Grounds

The Observatory Garden (now part of the Royal Park)

The Christie Enclosure (now part of the Royal Park)

1791 and work begins

Plans to enclose the courtyard were put into action by Maskelyne while his extension to Flamsteed House was under construction. Known originally as the Front Court, Maskelyne was given the go-ahead to enclose it in early 1791 (WORK16/126). The boundary on the west side of Flamsteed House was realigned at the same time, by moving it outwards a few feet so that it lined up with the western wall of the adjoining summerhouse.

The Observatory in 1736 before the courtyard was enclosed from the Park. Detail from Prospect of Greenwich from the Observatory... . Engraved by St. Torres after J. Rigaud, 1736. Printed for Robert Wilkinson London (No. 58 Cornhill)

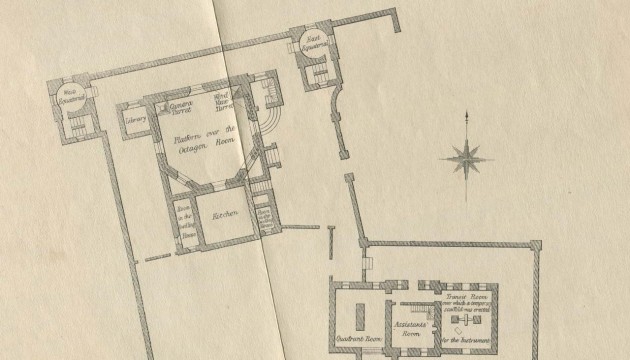

Plan of the Observatory in 1788 (detail) before the courtyard was enclosed. Redrawn by Airy from Roy's original. From the 1862 volume of Greenwich Observations

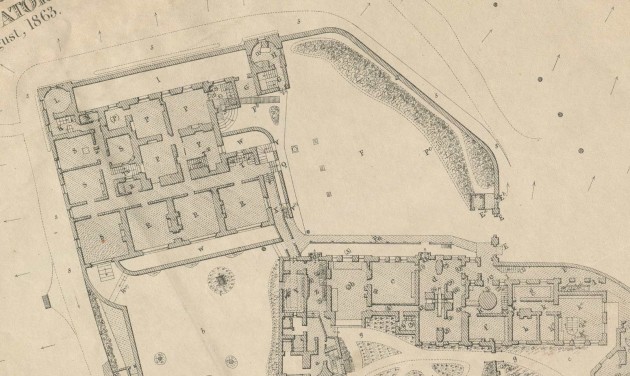

Plan of the Observatory in 1863 (detail). Key: F (courtyard), Fc (fire-plug), E (the single and double entrance gates), Ea (porter's lodge), Eb (Shepherd Gate Clock). From the 1862 volume of Greenwich Observations

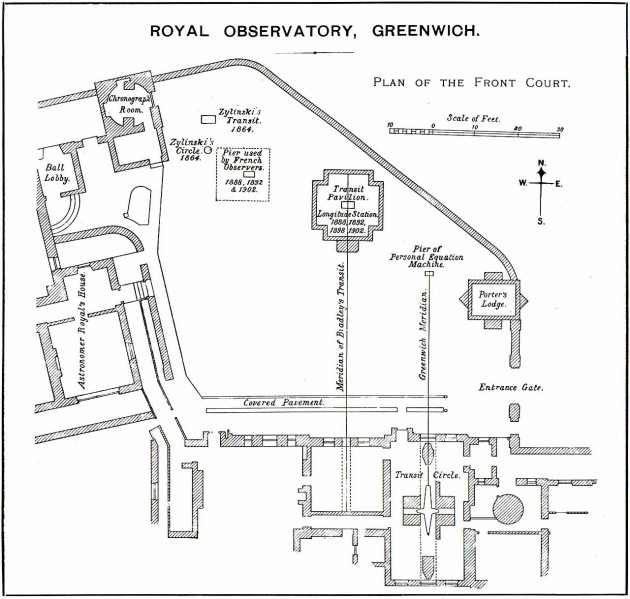

Plan of the Front Court (courtyard) in 1902. Plate VI (detail) from Telegraphic determinations of longitude made in the years 1888 to 1902, HMSO (1906)

Made up Ground

The north-east corner of the courtyard where the tree now stands, consists of made-up ground, 124 loads of gravel having been brought in from Blackheath during the various works. The iron railings on the retaining wall facing the river are probably original. Openings (now permanently sealed) were introduced on the line of the Bradley Meridian in about 1816 and on the Airy Meridian in about 1850 to allow the meridian marks to the north to be viewed. The stone block by the earlier opening was erected on 13 October 1797 and carried a near meridian mark (now missing). Click here to read more about the stone block and meridian mark.

The entrance gates into the courtyard c.1866–73. The retaining wall below the railings on the right was rebuilt in the early 1840s. The chimney protruding above the gate clock belongs to the original Porter's Lodge. From a postcard published anonymously

The railings and retaining wall in the 1890s. The left arrow indicates the removable section of railings on the Airy Meridian. The Transit Pavilion (built in 1891) can be seen above it. The right arrow indicates the position of the opening (a gate) on the Bradley Meridian. The stone block that carried the meridian mark can be seen above it to the left. Between the block and the Transit Pavilion, a transit hut is also visible. The tall chimney (centre left) belongs to the gatehouse (completed in 1890). The gates into the courtyard (extreme left) were renewed in 1873–4. The clock indicates that the photo was taken at 6.25 in the morning. (See above for a plan of the courtyard in 1902). Detail from a postcard published by Henry Richardson.

The railings where they cross the Airy Meridian. The modified section was designed to be lifted out when required. Photo June 2009

The block that carried Maskelyne's Meridian mark. The gate inserted into the railings by Pond in about 1816 can be seen to its left. Photo June 2009

Creating the path beneath the northern wall

When John Robinson, the King’s Surveyor of Woods visited Maskelyne on 8 September 1790 to discuss the possible enclosure, they also discussed the creation of a ‘new walk’ directly beneath it to be created at Maskelyne’s own expense. This new path was surfaced with gravel, and over the years, the gradual crumbling of the hill, accelerated by the continual passage of large numbers of people exposed the foundations not just of the wall, but the whole of the northern and western faces of the house. To make matters worse, the North Terrace wall had bulged out considerably, probably as a result of ‘an injudicious mode of building and from the effects of water and frost’. In 1840/1 therefore, the front wall of the North Terrace was rebuilt and a flagged pavement ‘laid round the foundation of that part of the Court Wall which appeared to be in the greatest danger’.

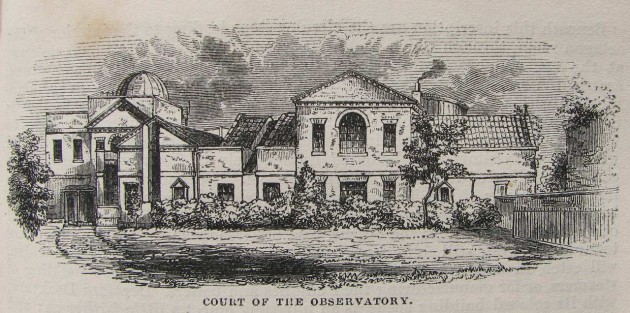

The appearance of the courtyard prior to1864

Apart from a wooden hut that served as a Porter’s Lodge, the courtyard appears to have been free of clutter until 1826, when a large reflecting telescope, bearing similarities to those of Herschel, was delivered and set up at its centre. Made by Ramage, it was dismissed by Airy as ‘useless’, and removed shortly after his arrival as Astronomer Royal in 1835. The courtyard remained largely clear of permanent structures for the next 50 years.

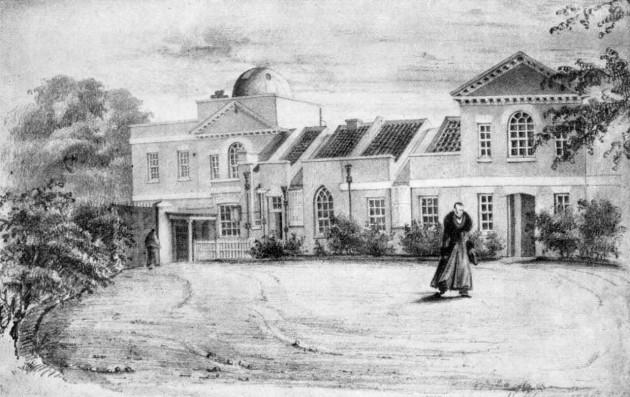

The courtyard in 1839. The figure in the centre is the Astronomer Royal, George Airy. From a drawing by Elizabeth Smith, 11 February 1839

The courtyard c.1850. The recently completed Transit Circle Room is on the left whilst Flamsteed House is on the right behind the railings. From London and its Vicinity exhibited in 1851, (John Wheale, London, 1851)

In 1857/8, a covered walkway was built along the southern edge along the side of the Meridian Building. This connected with an earlier covered way linking the western corner of the Meridian Building to Flamsteed House. The newer structure, (unlike the older one), was open to the elements at the side. In an attempt either to retain some privacy within the courtyard … or perhaps to prevent those staff working within the building from becoming distracted; it was screened off from the courtyard in Airy’s time with a high closeboard fence.

View from the east window of the dining room in Flamsteed House, looking across the roof of the covered passage and the Front Court. Watercolour painting by Chritstabel Airy dated 29 May 1856 (but completed in 1860). Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

The courtyard in about 1843-49. Watercolour painting by Henrietta Smythe. © The Scout Association Heritage Collection (see below)

The general ambience of the courtyard was described by the Stereoscopic Magazine in 1858:

At present it is a well-kept level of gravel, bordered on the side adjacent to the railings by flowering shrubs and trees. The effect of these, on entering the secluded precincts of the Observatory, is eminently agreeable, and the laburnums; lilacs, and rich crimson beech, the latter of which is the picturesque foliage by the side of the north-east dome, are graceful heir-looms which the present proprietors have not failed to appreciate and encourage to the utmost; and truly pleasant it is to see how the more delicate of our forest-trees, mingling with the broom, guelder-rose, and maythorn, and many more than we should care to name, have been permitted to share the enclosure devoted to the appliances of modern science, and how that their cheerful presence lends a charm to the discharge of the monotonous routine of daily duty.

The erection of observing piers and huts

In 1864 two observing piers were erected close to the eastern summerhouse for use by Otto Struve’s observers (which included Zylinski) in connection with the determination of the observations of longitudes of Bonn, Nieuport and Haverford-West. The piers were removed the following year. Their exact location can be seen on the 1902 plan (above).

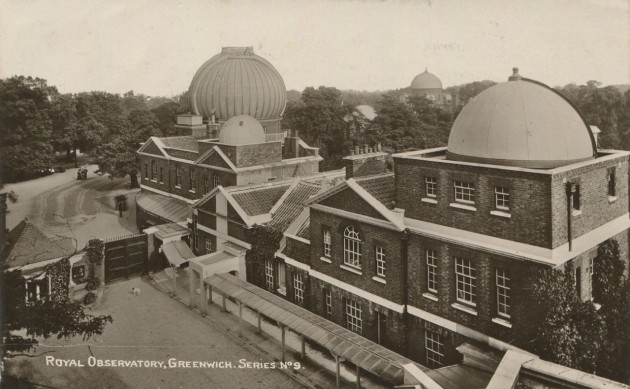

Christie carried out his own series of longitude determinations between 1888 and 1902. To facilitate these, two transit-huts from the Transit of Venus expeditions were erected in the courtyard and two brick piers built. That for the English observers was on the line of the Bradley Meridian. The one used by the French was 22 feet to its west and slightly to the north. The hut on the Bradley Meridian was replaced in 1891 by a brick built Transit Pavilion. Soon after his arrival as Astronomer Royal, Dyson arranged to borrow the Cookson Floating Zenith Telescope and its hut from the Cambridge Observatory so that he could carry out investigations into the variation of latitude. The hut, which was wooden with a tiled roof, was erected in August 1911, roughly where the French Observer’s Hut had previously stood. When the telescope was moved to a new building in the Christie Enclosure in 1936, the old hut was put to use as a store. In 1948/9, it was fitted up to accommodate a petrol-driven generator which had been obtained in order to have a standby power-source for the quartz clock installation. The hut was demolished along with the Transit Building in 1959/60.

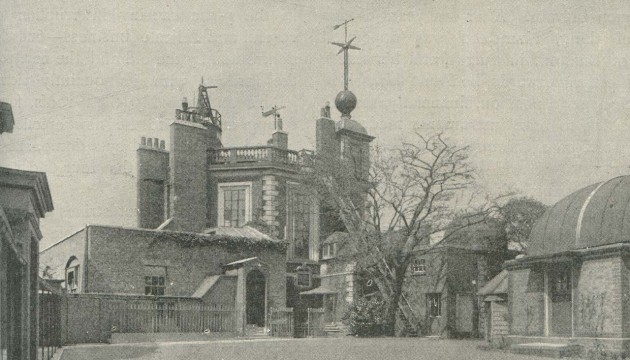

The courtyard in 1896. The building on the right is the Transit Pavilion erected in 1891. To its left, part of a wooden Transit Hut can be seen. It was used by the French observers when the longitude of the Paris Observatory was determined. From a London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company photograph published in volume II of Pearson's Magazine

The courtyard in about 1908 following the upgrading of the covered walkway and entrance porch to Flamsteed House in 1906/7. The wooden Transit Hut is no longer present. From a postcard published anonymously, but probably by Perkins and Son (P&S)

The courtyard in about 1928. The building to the left of the Transit Pavilion is the hut that housed the Cookson Floating Zenith Telescope. From a postcard published by the Royal Observatory, Greenwich

The view across the courtyard towards the Great Equatorial Building c.1893–1908. From a postcard published by Henry Richardson Ltd

The new Porter's Lodge

In 1888/9, the Admiralty sanctioned the building of a new Porter’s Lodge or Gate House. It was completed in the autumn of 1890, leaving the courtyard clear of building work for a few months before work on the Transit Pavilion commenced in the Spring. The work on the Transit Pavilion took longer than anticipated because of problems with the semi-domes. Meanwhile, a temporary canvas tent was erected over the telescope until these were finally put in place in October 1891.

The view across the courtyard from Flamsteed House towards the Great Equatorial Building c.1908. Chrisite's Porter's Lodge can be seen on the left. The rear of the gate clock is visible between the Lodge and the double gates. From a postcard published by Henry Richardson Ltd

The same view from around 1925–31. Note the replacement gates into the courtyard. They were erected in January 1923. From a postcard published by the Royal Observatory, Greenwich

The Personal Equation Machine

The personal Equation Machine for use with the Airy Transit Circle was erected in 1885 on a specially built pier in the courtyard, directly on the line of its meridian. Its position is marked on the plan above. A description of the instrument was published in the introduction to the 1885–99 volumes of Greenwich Observations.

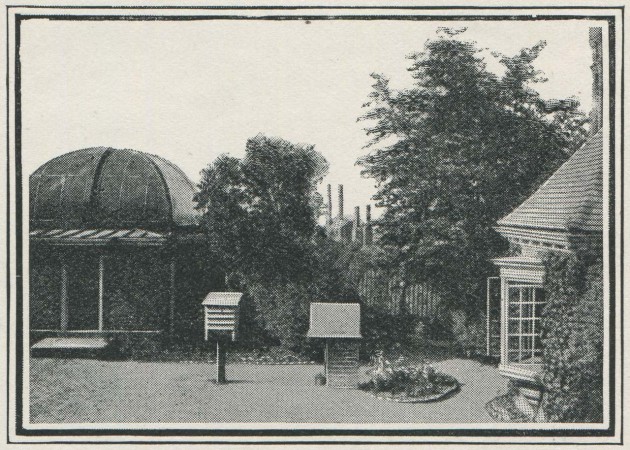

The ‘Exterior Thermometer’

On 18 July 1896, a screen was erected on a stand in the courtyard close to the Personal Equation Machine between the Transit Pavilion and the Porter's lodge to house the ‘Exterior Thermometer’ used in conjunction with the Airy Transit Circle. Prior to that date, it had been mounted on the north facing wall of the Meridian Building where it was carried by an arm projecting from the wall at a distance of 4½ feet at a height of nearly seven feet from the ground. On 23 February 1922, when the support to the Thermometer Stand was being renewed, the Stand was moved a few feet into a more open position practically on the Meridian. A few weeks later, on 27 March, a new Thermometer Stand was also erected in the garden, south of the Transit Circle.

The view northwards across the Courtyard from in front of the Airy Transit Circle. From left to right: 1. the Transit Pavilion, 2. the stand housing the External Thermometer, 3. the Personal Equation Machine with Greenwich Power Station behind, 4. the Porter's Lodge. The External Thermometer and Personal Equation Machine were both used in conjunction with the Airy Transit Circle. From The Graphic, 23 June 1906, p.819

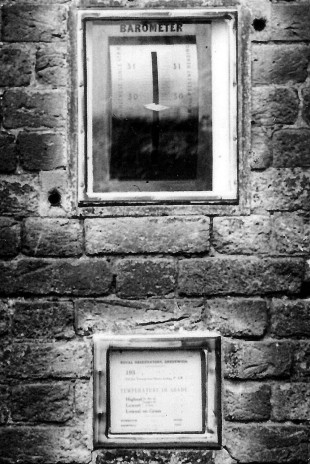

The barometer installed in 1864 and below it, the card giving the highest and lowest readings of the thermometer. Supplied by Negretti & Zambra (London), the left hand scale of the barometer records the highest pressure since 9.00 the previous evening and the right hand scale the lowest. This is explained in the text to either side. The barometer tube (not visible here) was encased from behind to protect it

The Gate clock, Standard Measures and and other information for the public

When the courtyard was first enclosed, the north side was bounded with a retaining wall surmounted by railings, and the east side by a wall, pierced by a pair of double gates for vehicles with a smaller pedestrian gate to their left. To maintain the symmetry, a dummy recess was created to the right to balance the pedestrian gate to the left. This proved an ideal location for the 24-hour Shepherd Gate Clock in 1852. This was the first public clock in England to show accurate Greenwich Mean Time. According to the Journal of the Astronomer Royal (RGO6/25), the frame of the Gate Clock was inserted into the wall on 20 May, with the Clock coming into use on Friday 13 August. It wasn’t too long before it was joined by a variety of other public instruments and standards, which were all mounted on the wall to the left of the gate.

The installation of the length standards was begun on Wednesday 26 January 1859 and completed a few days later on Saturday 29 January (RGO6/25/172). The earliest known published reference to them is in the 5 October 1861 edition of Chamber’s Journal.

A public barometer was installed on 2 June 1864 (RGO6/26)), a glass case with a card, giving the highest and lowest readings of the thermometer in the preceding twenty-four hours (1870/1) and a public balance in 1873 (preparations for its installation having commenced on 3 September (RGO6/26/187)). The balance, which was mounted behind a small pair of opening doors set into the wall, was only made available during office hours. It was not a success. The hole through which it was accessed was bricked up and the doors removed. It was reopened in 1894 so that a Post Office letterbox requested by Christie could be mounted there (it was replaced with a taller larger box during the reign of George V).

The public length standards, public barometer and card giving the highest and lowest readings of the thermometer in their original positions in about 1930. From a postcard published by the Royal Observatory, Greenwich

The length standards (left), public barometer, Post Office letter box, gates to the Courtyard and Shepherd Gate Clock (centre) in about 1935. From a postcard by Daniell Brothers Ltd., Lewisham

A metal plate stating the height above sea level was mounted next to an old bench mark on the left hand gate pillar. Although its date of its arrival is unrecorded, it seems likely that it was put up in the 1860s. It carried the words:

154.0 FEET ABOVE MEAN WATER AT GREENWICH

155.7 FEET ABOVE MEAN WATER AT LIVERPOOL

In 1931 or 1932, an Ordnance Survey flush bracket (S0646) was mounted over the old bench mark. A couple of yers later, the metal plate was replaced with one of stainless steel carrying a new inscription. This was reported by Spencer Jones in the 1934 annual report to the Board of Visitors in 1934, Spencer Jones as follows:

‘A new engraved “staybrite” plate has been fixed outside the main entrance to the Observatory. It adjoins a flush bracket placed by the Ordnance Survey Department over an old bench mark cut on the wall, and gives the corresponding height above sea level at Newlyn (154.70 feet)’.

The replacement flush bracket and stainless steel plate in about 1935. Detail from a postcard published by Royal observatory, Greenwich

Replacing the gates

From time to time the double gates needed replacement or repair. On 25 July 1836, they were taken down to be heightened (RGO6/24). The sequence of images below shows the different gates that were in place until 1938.

The Courtyard gates c.1870. Known to be present in 1839, they were replaced in 1873/4. It is not know if it was these gates or an earlier set that was heightened in 1836

The same gates in the early 1890s. Note the new Porter's Lodge on the right and the length standards on the wall on the left. To the right of these, the public barometer is visible. The patch of lighter brickwork to its right is where the public balance had previously been mounted. Photo date 1891–94. Detail from an image from an unknown publication

In about 1905, the gates were replaced with the ones shown here. Not long afterwards, they were replaced by the previous set, which by then had been strengthened at the bottom. It is not known if the gates were originally intended to be temporary, or if they were disliked and ordered removed by the Astronomer Royal because of the negative effect they had on his privacy. Detail from a postcard published by Daniell Brothers, Lewisham

The former gates in about 1906–09 after they had been rehung. They remained in situ until January 1923 when they were replaced by what appears to have been the short-lived gates of 1905. From a postcard by Perkins and Son

The replacement gates in about 1933–37. They were replaced by others of a different design in 1938, this last set being destroyed on 15 October 1940 by a direct hit during the Second World War. Note the GPO letterbox mounted in the wall immediately to the left of the left-hand figure. From a postcard published by Daniell Brothers, Lewisham

Wartime Damage

On 15 October 1940 the gates and pillars were destroyed by a direct hit. The gateway was boarded up with makeshift gates. Permanent gates and pillars (but not the flushbracket) were eventually put up in 1945/6 and a new flush bracket (G1692) installed between 1946 and 1949 in a position roughly 30 feet further to the north on the eastern wall of the gatehouse (close to its NE corner and at about knee height). Although not immediately replaced when the gate pillars were first erected, the stainless steel Newlyn height plate (or perhaps a new version with a slightly different design) was eventually put up in time for the opening of the Octagon Room as a museum by HRH The Prince Philip on 8 May 1953. Although originally mounted off centre on the pillar, it was placed centrally with what appears to be a small object label immediately to its right (as can be seen below).

As well as destroying the gates, the blast also destroyed the covered walkway and damaged the public barometer, Gate Clock and Gate House. The barometer was back in action by 1945/6 and the clock in 1946/7. The Gate House was also repaired, the repairs being completed in 1946/7.

Changes for Museum use

In 1954, the Department of Works drew up proposals for the future use of the buildings and grounds. They show that at that time, the plan was to retain the Transit Pavilion and demolish the Cookson Hut and Gate House whilst at the same time realigning the eastern boundary and replacing the wall with railings.

Although the Plans for the Cookson Hut didn’t change, those for the Transit Pavilion and Gate House did. During a ministerial visit took place on 22 April 1958, Hugh Molson (the minister) indicated that he wanted the Gate House retained.

By early 1960, the plans for the railings had changed. Park Lane, which runs alongside Hyde Park in central London was about to be widened and sections of railings and gates were about to become available for use elsewhere. Some from the Cumberland gate area near Marble Arch were allocated to Greenwich. This caused a rethink of the boundary treatment, which included following the original boundary more closely. Because the new railings were different in style to those that already existed at the Observatory, it was thought that it would be beneficial from a visual point of view, to demolish the Gate House and erect a wall on its foundations to carry the Gate Clock – the wall providing a break-point between the two set of railings. During 1959, after much double-checking, a final decision to demolish the Cookson Hut and Transit Pavilion was made towards the end of the year. Although the Minister’s views regarding the Gate House were considered, he was now an ex-minister and in March 1960 the various parties agreed to its demolition too.

When the wall was demolished, the length standards were moved to their current position under the Gate Clock, and the barometer put into store (NMM Object ID: ZBA4519). The height plate, was originally scheduled to be placed to the left of the gates, close to its original position, but instead, was placed between the clock and length standards – and almost certainly at the incorrect height!

The Gate Clock, length standards and Newlyn plate in their new positions in about 1970. Photo courtesy of Patrick Moore

Meanwhile, back in 1955, in a report dated 11 July, a certain JH Davy was the first to express the view that the Meridian Line should be marked on the ground in the courtyard – at that time, it was only marked on the path outside. His idea was acted on and today it is the most popular attraction in the whole of the Observatory. The press release issued to coincide with the Royal Opening in July 1960 stated: ‘The Meridian is marked across the courtyard so that visitors can indulge in the conceit of being photographed standing with a foot in each hemisphere.’ At that time the courtyard was surfaced with gravel, as it had been in Airy‘s time. Today’s granite setts date from 1967. Click here to read more about the marking of the Meridian in the courtyard.

The changes of 1993

... to be continued.

Image licensing

The image reproduced courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library has been cropped from the original to exclude the margins, reduced in size, is more compressed than the originals and has been reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

The painting by Henrietta Smythe is reproduced by kind permission of The Scout Association Heritage Collection. Henrietta Grace Smythe (1824–1914) was the sixth of eleven children born to Captain (later Admiral) William Henry Smythe (1788–1865), a distinguished astronomer, fellow of the Royal Society and a member of the Observatory’s Board of Visitors from 1836 until his death. One of Henrietta’s two older brothers, Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819-1900), became Astronomer Royal for Scotland in 1846. The other, Warrington Wilkinson Smythe (1817–90), married Anna Storey Maskelyne, granddaughter of the fifth Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne. In 1846, Henrietta married Baden Powell, the Savilian Professor of Geometry at Oxford who was 28 years her senior and previously twice married. Widowed in 1860 shortly after the birth of her tenth child, she changed the family name to Baden-Powell. Her son Robert was the founder of the Scout Movement.

© 2014 – 2025 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan