…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

The Astronomers’ Garden (formerly the Upper Garden)

By the 1940s, the Observatory’s main site at Greenwich occupied an area of 2.46 acres. The area currently known as the Astronomers’ Garden occupies about 0.09 acres (400 m²) of this total.This part of of the website deals only with the Astronomers’ Garden. Other parts of the Observatory Grounds are covered in the following sections:

The Courtyard

The Meridian Garden

The Garden to the west of Flamsteed House

The Magnetic and South Grounds

The Observatory Garden (now part of the Royal Park)

The Christie Enclosure (now part of the Royal Park )

A garden of many names

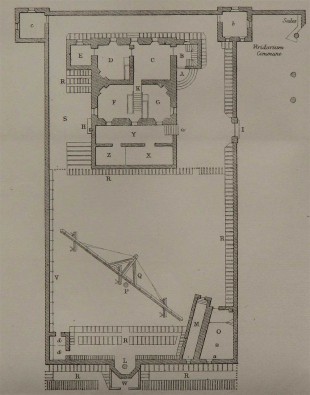

Plan of the Observatory c.1676. Redrawn by Airy from an engraving by Francis Place after Robert Thacker and published in the 1862 volume of Greenwich Observations

The garden in Flamsteed's time

In Flamsteed’s time, the garden was over twice its current size and mainly laid to lawn. It occupied the southern half of the Observatory site.

Features in the garden which can be seen in the adjacent plan include flower gardens (R), and a store for the 60-foot telescope tube of the mast telescope (V). To the south of the main building (and demolished between 1847 and 1861), were two adjoining necessary houses or toilets (d,d). They were in the south-west corner, whilst in the south-east corner, a small detached building, aligned to the meridian, housed Flamsteed's main observing instruments. It contained the Quadrant House (M) and the Sextant House (O). Between the two buildings, there was a sundial (L). Immediately to its south and set below it into the retaining wall, there was a small Garden Room or potting shed (W). This opened directly out onto the park, but is also thought to have been connected to the vicinity of the basement of the main house by a subterranean passage. The mast telescope (P & Q) is last recorded in 1690 and had been removed by 1699. After its removal, there was less reason to keep a large expanse of lawn. The vegetable garden (S) to the west of Flamsteed House was later built on.

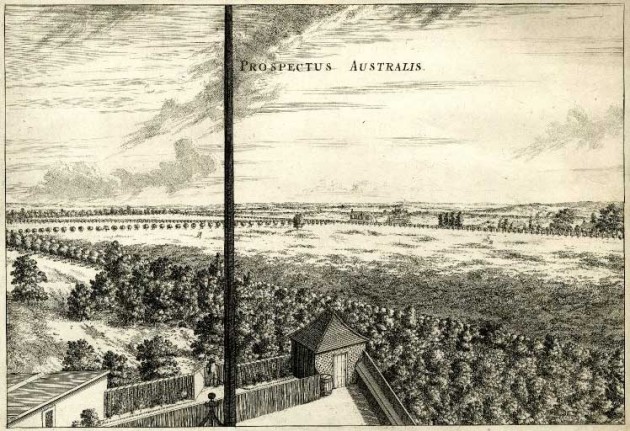

Looking south over the garden c.1676. The mast of the Flamsteed's mast telescope divides the view vertically. The Quadrant House is on the left and the necessary houses on the right. Between them, a man stands looking at the sundial. Engraved by Francis Place after Robert Thacker. © Trustees of the British Museum

The garden in the 1760s

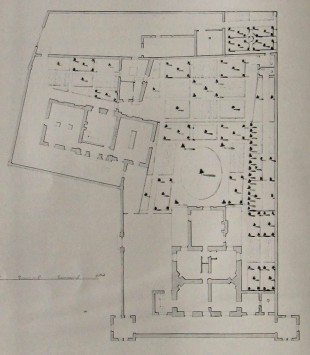

John Evelegh's plan of the Observatory. Drawn between 1750 and 1773 it was republished in QJRAS in 1963

John Evelegh’s plan of the Observatory which was drawn between 1750 and 1773 indicates that by then most of the garden was planted in a highly stylized manner in a checkerboard pattern with blocks of flowers interspersed with blocks of lawn, each block of lawn containing either one, or five small trees. The plan (right) was drawn with north at the bottom rather than at the top.

The garden between 1790 and 1835

The garden was reduced to its present size in 1790/1 when Maskelyne’s extension to Flamsteed House was built. There are no known plans or drawings that show the appearance of the garden from then until after the arrival of Airy and his family in the mid 1830s.

The garden from the 1830s onwards

Drawings in the archives at Cambridge (RGO/116) show that by 1836, the garden was laid to lawn with a smattering of small (fruit?) trees. It is believed to have remained largely the same until 2008/9 when the present hard landscaped gardens were laid out.

The garden in about 1845-49. The former Quadrant Room built by Bradley is on the left and the South Dome housing Airy's Altazimuth Instrument in the centre. Watercolour painting by Henrietta Smythe. © The Scout Association Heritage Collection (see below)

Underground features, the retaining walls and access to the Lower and Middle Gardens

The south retaining wall (west side) in January 2012. The building to the right is the Museum's Plant Room (formerly Airy's Garden House and before that the stables). From around the 1850s until about 1910, a set of steps ran down the wall from top right to a point roughly behind the tree in the foreground. The dwarf wall above the stone string course at the top of the wall was rebuilt in the second half of 2009. Airy records that the base of the dwarf wall was about 16 feet above the lower ground level

A subterranean passageway (which probably dates back to the time of the Greenwich Castle) runs beneath the garden from the an opening in the north retaining wall to the Museum’s Plant Room (the Garden Room in Flamsteed’s time). A large brick lined cistern is located towards the north-east corner of the garden. This is one of two underground cisterns that was in use to collect rainwater for use in the house prior to the Observatory being connected to the water mains.

Access from the garden to the Lower and Middle gardens (now known as the Observatory and Meridian Gardens) was always rather tricky. In 1835/6, Airy introduced two sets of steps down to the lower levels. One was on the southern edge of the garden and ran down the eastern side of the stables to the Middle Garden. The other was on the western edge of the garden and ran down the side of the retaining wall to the northernmost extremity of the Lower Garden. In 1856/7, Airy created a sloping passageway through to the Middle Garden by cutting though the bottom of the Altazimuth tower. By 1863, the 1835/6 steps down to the Lower Garden had gone, having being replaced by a subterranean passage that ran from the west end of the sunken passageway to the south of Flamsteed House to almost the same point in the Lower Garden. At the same time, a new set of steps to the Lower Garden was built that ran down the south retaining wall, on the west side of the stables. These, together with the underground passageway became unusable in 1894/5, when the ground they led to was planted over with shrubs as part of a landscaping scheme orchestrated as part of a general improvement to the Park in this vicinity. The steps appear to have remained until removed by Dyson in around 1910/11, the gap left at the top of the retaining wall being filled with a short section of iron railings. These were removed and replaced by brickwork in 2009/10 when the top of the dwarf wall at the top of the retaining wall was rebuilt. The National Maritime Museum’s destruction of this part of the garden’s earlier history has to be regarded as regrettable.

Remodelling by the National Maritime Museum

After the garden passed into the hands of the National Maritime Museum in 1960, it underwent a number of minor remodellings to accommodate the wear and tear caused by ever increasing numbers of visitors and in 2005/6 to accommodate an external lift for Flamsteed House. DDA-compliant and Mint Green in colour, this was installed at a cost of £163,000.

The east side of the garden in April 2005. The apple tree, a survival from the days of the working observatory, was felled later that year. When the Museum took over the garden in the 1960s a number of trees still grew there. The apple tree was one of just two that still survived in 2005. The last remaining tree, a flowering cherry, was felled in 2009. The manhole cover in the lawn covers the top of the underground cistern

On 1 October 1998, as a publicity exercise in the run up to the millennium celebrations, a rose garden was created on the southern edge of the lawn to commemorate the 1884 Meridian Conference. Representatives from all the voting nations at the original conference were invited to plant a specially named new rose – The Home of Time. Ten years later, the rose garden had out-served its usefulness and was ripped up to make way for the present hard landscaping. This work was carried out in 2008/9. A contribution of £163,000 for this and the hard landscaping carried out at the same time in the Meridian Garden came from the reserves of the Friends of the Museum, a charitable organisation that was wound up in 2007 (Museum Report, 2009).

The north side of the garden in May 2007. The paving in front of the railings was widened at the western end when the external lift when it was installed

The west side of the garden under snow in February 2009. Although work on the hard landscaping had commenced, this part of the garden remained unaffected at that time

The decision to hard landscape came about as result of decisions made by the Museum on how to route visitors through the site. Originally, it had been proposed to keep the rose border and turn the rest of the garden into a buggy store and picnic area. The adopted design was developed by PBA Consulting. Containing large amounts of hard landscaping, it was described as an Italian Garden, and features the famous dolphin sundial designed by Christopher St.J.H. Daniel as its centrepiece. This was relocated from the gardens of the main site of the National Maritime Museum. The York Stone paving, like that in the Meridian Garden was recycled from the grounds of the National Maritime Museum where it needed to be cleared to make way for the Sammy Offer Wing.

The top of the cistern in May 2009 after it had been 'discovered' by the contractors. Built from brick, it was designed to store water and is slightly deeper than it is wide. The two men are clearing earth from its north-east corner. The earliest record of the cistern's existence dates from the around the 1760s

A failure of corporate memory together with a lack of interest in the garden’s earlier history, meant that although well documented, the presence of the cistern beneath the garden was not known about by those involved until it was revealed during clearance works. As far as is known, a geophysical survey has never been carried out to investigate possible remains from Greenwich Castle. Regrettably, the substantial quantities of concrete poured as part of the landscaping works are likely to limit the effectiveness of any such survey in the future.

Looking south in April 2009. The gap in the wall blocked by railings where steps once descended to the Lower Garden is visible in the centre of the picture. The cherry tree to its left is flowering for the last time before being felled

The same view a year later in April 2010. The cherry tree has gone and the dwarf wall on the right rebuilt

Image licensing

The painting by Henrietta Smythe is reproduced by kind permission of The Scout Association Heritage Collection. Henrietta Grace Smythe (1824–1914) was the sixth of eleven children born to Captain (later Admiral) William Henry Smythe (1788–1865), a distinguished astronomer, fellow of the Royal Society and a member of the Observatory’s Board of Visitors from 1836 until his death. One of Henrietta’s two older brothers, Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819-1900), became Astronomer Royal for Scotland in 1846. The other, Warrington Wilkinson Smythe (1817–90), married Anna Storey Maskelyne, granddaughter of the fifth Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne. In 1846, Henrietta married Baden Powell, the Savilian Professor of Geometry at Oxford who was 28 years her senior and previously twice married. Widowed in 1860 shortly after the birth of her tenth child, she changed the family name to Baden-Powell. Her son Robert was the founder of the Scout Movement.

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan