…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

Photoheliographic Observations (1873–1976)

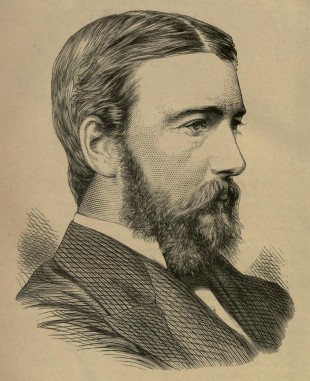

The World’s first programme of regular photographic observations of the Sun began in 1862 at the private observatory of Warren De la Rue in Cranford, the observations being made with a photoheliograph of De la Rue’s own design. In 1863, the photoheliograph was transferred to Kew, where the programme continued for a further nine years under De La Rue’s supervision, before being terminated in 1872. The following year, the photoheliograph was loaned to the Royal Observatory.

The Photoheliographic programme of the Royal Observatory ran at Greenwich from 1873 until 1948 and at Herstmonceux from 1948 until the end of 1976 when it was formally brought to an end by Richard Woolley. Given the importance of the work, it was taken up by the Heliosphysical Observatory, Debrecen, Hungary, where a programme of observations continues to this day.

The origins of the programme at Greenwich

The rise of astrophysics and the funding of science in Victorian Britain

By the 1860s, there were widely differing views within the British scientific community about the ways in which the future development of science should occur. George Airy, the Astronomer Royal, was very much of the view that Science was best served by private rather than public enterprise. In the opposite camp was Lord Wrottesley, who in earlier years had had a private observatory less than a mile from the Royal Observatory at his then house in Blackheath. A founding member of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) and a member of the Observatory’s Board of visitors from 1843 until his death in 1867, Wrottesley was a passionate believer in the need for more state involvement in the organisation and funding of scientific activity. He served for sixteen years as Chairman of the Parliamentary Committee of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Although astronomical research on the continent was generously supported by the state, in Britain such research was usually paid for out of the pockets of educated and wealthy gentlemen (the so-called Grand Amateurs) such as Huggins, Lassell and De la Rue.

In 1868, a year after Wrottesley’s death, Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Strange and (Joseph) Norman Lockyer vigorously took up the cause for more state involvement in science. Two years later, a Royal Commission was set up to inquire into Scientific Instruction and the Advancement of Science. The Chairman was William Cavendish, the seventh Duke of Devonshire, who for many years had served on Wrottesley’s committee. The commission sat from 1870–75 and produced a large number of reports. Amongst its members was George Stokes who since 1860 had been a member of the Observatory’s Board of Visitors. Its secretary was Norman Lockyer. A civil servant and journal editor, Lockyer was also a solar astronomer, a fellow of the RAS and a junior member of its Council. There he was disliked by many – in part because of his lobbying for the setting up of a state funded solar physics observatory of which he anticipated being the head. The Council was heavily influenced in its decision making by Airy who was also President of the Royal Society from 1871–3.

The decision to photograph the 1874 Tranist of Venus

Meanwhile, against this background, plans were being drawn up at Greenwich for a British expedition fo observe the 8 December 1874 Transit of Venus (the first to occur since 1769). They built on a lecture On the Means which will be available for correcting the Measure of the Sun’s Distance, in the next twenty five Years that had been given by Airy to the Royal Astronomical Society in 1857.

In 1868, Airy began a correspondence with the Hydrographer of the Navy about funding for a British expedition. Although there had been discussion of the application of photography, photographic methods were excluded from the estimate for the expenditure of a sum of £10,500 that was put before a parliamentary committee and approved on 6 August 1869 (click here for Hansard report). Not everyone was happy at the exclusion of photographic observations, particularly the Royal Observatory’s own Board of Visitors who at their meeting on 5 June 1869 had resolved:

‘that in their opinion it would be desirable to make provision for the Photographic record of the phenomena in addition to the preparations already contemplated.’ (ADM190/4)

and as a result, at their annual meeting on 4 June 1870, the Observatory’s Board of Visitors resolved that

‘Mr warren De la Rue [who had been on the board since 1864] be requested to confer with the Astronomer Royal with the view of organizing a plan for photographic observations of the Transit of Venus, and for preparing an approximate estimate of the probable expense.’ (ADM190/4)

At their next meeting on 3 June 1871, they went further and

‘Resolved, that as this Board deem it most important that Photographic be combined with eye observations at the approaching Transit of Venus, an opinion in which the Astronomer Royal fully concurs, the Chairman [Edward Sabine] apply to the Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Treasury to sanction a grant of Five Thousand Pounds (£5000) for the purpose, a sum which it is considered will cover the cost of photographic apparatus and observations for all stations.’ (ADM190/4)

Following further correspondence with Airy, the Admiralty agreed to provide the additional £5000. At this point, an order was paced with Dallmeyer for five photoheliographs, their construction being overseen by De la Rue.

Airy bites the bullet – a photographic and spectroscopic department for Greenwich

Prior to 1872, Airy had shown no interest in instigating a programme of systematic observations of the Sun at Greenwich. This would probably have remained the case if it hadn’t been for the setting up of the Royal Commission and the pressure being brought to bear on the Government for more publically funded science and a dedicated astrophysical observatory, the imminent cessation of the solar programme at Kew, the presence of De La Rue on the Board of Visitors, and crucially, the question (at that point still unasked) of who would take control of the Dallmeyer Photoheliographs once the Transit of Venus expedition was over.

Part of the reason for Airy’s original reluctance to do anything other than dabble in the new science of astrophysics can be put down to his insistence of sticking to the narrow terms of the Royal Warrant by which he had been appointed in 1835. This required him forthwith to apply himself ‘with the most exact care and diligence to the rectifying [of] the tables of the motions of the heavens and the places of the fixt stars in order to find out the so much desired longitude at sea for the perfecting [of] the art of navigation’ (RGO6/1/193). Others had no such constraints. The duties of the Astronomer Royal for Scotland, for example, were much wider, being ‘… to apply himself with diligence and zeal … for the extension and improvement of Astronomy, Geography and Navigation and other branches of Science connected therewith’. In 1872, Airy suddenly suggested widening his remit in a pragmatic response to the long running debate, which by then was nearing its climax.

Amongst those who gave evidence to the Commission in 1872 were Strange, Airy, and two members of the Observatory’s Board of Visitors: De la Rue and Spottiswode. Amongst other things, they (and others) were asked for their views on the desirability of a state funded solar physics observatory and about how such an observatory might be organised.

Airy, was no doubt struck by the similarity with the situation that he had found himself in in 1840 as a result of Sabine’s campaign for state support for a whole string of sea and land based magnetic observatories. On that occasion, he had seen off a proposal by John Lubbock for a new magnetic observatory in the vicinity of London by offering to do the work at Greenwich at considerably lower cost.

Stuck between a rock and a hard place, Airy’s options were limited. Either he could allow the work of the Observatory to continue unchanged and in all likelihood see an independent astrophysical observatory established where the work carried out by De la Rue at Kew would be continued and enhanced; alternatively, he could suggest to the Board of Visitors that the Royal Observatory should take on the work that had now ended at Kew and thereby not only potentially fend off the establishment of a rival institution, but also ensure (such was his conviction), that such work that was done would be done in a well organised and efficient manner under his supervision. He chose (no doubt reluctantly) the latter option. His suggestion was taken up by the Board which resolved not only that the Observatory should record the presence of sunspots, but that it should also undertake spectroscopic work. Although De la Rue was the proposer, his private thoughts on the matter are unclear as his views on the public funding of science were very different to those of Airy and more in line with those of Strange. From a pragmatic point of view however, he probably reasoned that it was better to have the future of the work assured (even if potentially limited in scope) rather than waiting for the possible establishment of an alternative institution that might never materialize.

The political manouverings

For those who are interested in the political manouverings, the timing of events was as follows:

1872, March. Observations with the Photoheliograph end at Kew.

1872, April. Strange’s paper On the Insufficiency of Existing National Observatories is published.

1872, April 24. Strange gives evidence to the Royal Comission. Click here to read.

1872, April 26. Airy gives evidence to the Royal Commission. Click here to read.

1872, May 8. Strange gives further evidence to the Royal Commission. Click here to read.

1872, May 10. Airy finishes writing his 1872 address to the Board of Visitor. At the end of which he wrote:

‘I have now to offer to the notice of the Board another subject, not less important.

The tendency of late discoveries and consequent discussions in astronomy has been, not to withdraw attention from the exact departments of astronomy, but to add greatly to the public interest in those which are less severely definite. And this has become so strong, that I think it may well be a subject of consideration by the Board of Visitors whether observations bearing upon some of those trains of discovery should not be included in the ordinary system of the Royal Observatory.

The criteria which, as appears to me, may be properly adopted in the selection or rejection of subjects of observation, are these. Observations which can be made at any convenient times, which do not require telescopes of the largest size, and which do not imply constant expense, ought to be left to private observers. Observations which demand larger telescopes, and especially observations which must be carried on in continual routine and with considerable expense, can only be maintained at a public observatory. The claims of each subject must be separately considered; but there can be no doubt that a very powerful demand for attention is made, when private persons have been induced to continue observations for a long time at considerable current expense, and when plausible evidence is given of the connexion of results thus obtained with other cosmical elements.

I think that these considerations exclude measures of double stars at the Royal Observatory, but they leave an opening for the scrutiny of nebulae, planets, &c., and possibly (but I speak in doubt) of solar spectroscopy. But I have no doubt that they fully sanction the undertaking a continued series of observations of solar spots.

If the Board of Visitors should judge that these observations ought to be taken up, I would request them to observe that another assistant must be added to the Observatory Establishment. For the present, little would be required in the nature of instruments.

The character of the Observatory would be somewhat changed by this innovation, but not, as I imagine, in a direction to which any objection can be made. It would become, pro tanto, a physical Observatory; and possibly in time its operations might be extended still further in a physical direction. There would be no difficulty in maintaining its efficiency under the present system of superintendence.

Indeed, the Observatory has long been a physical Observatory, by virtue of its Magnetical and Meteorological Department; the systematic observations in which are, as I believe, the best in the world. They remove all necessity of subvention by the Government to any other magnetical or meteorological observatory in this part of Britain.’

(Click here to read this part of the report as originally published)

1872, May 10. Airy goes to the RAS for a Council and general meeting (RGO6/26)

This took place just hours after Airy had completed writing his address to the Visitors. The Council meeting began at 15.30 and was the first since Strange and Airy had given evidence to the Commission (the previous meeting having been held on 12 April. In total 18 people were present.

Cayley* (in the chair), De la Rue* (vice-president), Huggins*, Lassell*, Whitbread, Dunkin (Assistant at Royal Observatory & Secretary to the Society), Proctor, Strange (foreign secretary), Airy (Astronomer Royal), Browning, Burr, Buckingham, Christie (Chief Assistant at Royal Observatory), Knott, Main* (formerly Chief Assistant at Royal Observatory), Noble, Pritchard* & Ranyard.

* Member of the Observatory’s Board of Visitors

Right at the very end of the meeting, Strange proposed with De la Rue seconding that:

‘The President be authorised on behalf of the Council and Fellows of the Royal Astronomical Society to bring before the Royal Commission on Scientific Instruction and the Advancement of Science now sitting the extreme desirability of providing for the cultivation of the Physics of Astronomy’. (RAS papers 2.7, Council Minutes).

After some discussion (not recorded) the motion was adjourned to the next meeting (14 June).

1872, June 1. Meeting of the Observatory’s Board of Visitors

Attended by Cayley (in the chair), Challis, De la Rue, Huggins, Lassell, Main, Price, Richards, Spottiswode, Stokes and Willis. Proposed by De la Rue, seconded by Huggins and unanimously resolved:

‘That in the opinion of the Board, the time has arrived when it would be for the advantage of Science that continuous photographic and spectroscopic records of the Sun should be made at the Royal Observatory. They therefore trust that the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty will authorize the necessary steps being taken by the Astronomer Royal to commence such observations with as little delay as possible.’ (ADM190/4)

1872, June 14. Spottiswode gives evidence to the Royal Commission

Spottiswode was, on the whole, against the setting up an independent solar physics observatory. Click here to read his evidence.

1872, June 14, RAS council meets

In total 15 people were present, Airy was notably absent as were two members of the Board of Vistors who had attended the previous meeting (Main & Pritchard)

Cayley* (in the chair), De la Rue*, Huggins*, Lassell*, Whitbread, Dunkin (Assistant at Royal Observatory), Proctor, Strange, Browning, Burr, Buckingham, Christie (Chief Assistant at Royal Observatory), Knott, Noble, & Ranyard.

* Member of the Observatory’s Board of Visitors

The rough minutes (RAS papers 3.4, Rough Council Minutes) show that it was decided early on in the meeting to defer discussion of Strange’s proposal until a special meeting on 21 June. Interestingly, the signed off minutes (RAS papers 2.7, Council Minutes) imply that the matter was not touched on until the end of the meeting ,

1872, June 21, RAS council meets

The following 14 people were present:

Cayley* (in the chair), De la Rue* (vice-president), Huggins*, Lassell*, Dunkin (Assistant at Royal Observatory & Secretary to the Society), Proctor, Strange (foreign secretary), Airy (Astronomer Royal), Browning, Burr, Christie (Chief Assistant at Royal Observatory), Knott, Lockyer & Ranyard.

By the end of the meeting, the following resolution (as originally proposed by Huggins and seconded by Burr but with subsequent slight ammendments) had been agreed:

1. That the President be authorised, on behalf of the Council and Fellows of the Royal Astronomical Society, to bring before the Royal Commissioners on Scientific Instruction and on the Advancement of Science, now sitting, the importance of further aid being afforded to the cultivation of the Physics of Astronomy.

2. They think such aid would be most effectually given by increased assistance when needed to existing Public Observatories in the direction recommended by the heads of those observatories, especially that at the Cape of Good Hope, and by the establishment of a new Observatory, on the Highlands of India, or in some other part of the British dominions where the climate is favourable for the use of large instruments.

3. The Council do not recommend the establishment of an independent Government Observatory for the cultivation of Astronomical Physics in England, especially as they have been informed that the Board of Visitors of the Royal Observatory at their recent meeting recommended the taking of Photographic and Spectroscopic records of the Sun at that Observatory.

With time running out, discussion of a proposed ammendment was held over for another meeting which it was agreed to hold on 28 June.

According to the minutes, the suggested ammendment, which had been proposed by Strange and seconded by De la Rue, was that the following be substituted for the second clauses:

The following seems to the Council to be the provision now requisite:

1. An Observatory, with a laboratory and workshop of moderate extent attached to it, to be established in England for the above researches.

2. A certain number of Branch observatories, to be established in carefully selected positions in British territory in communication with the Central Observatory in England, for the purpose of first, giving to Photographic Solar Registry that continuity which experience has already proved to be necessary and secondly, to investigate the effect of the Earth’s Atmosphere on Physico Astronomical researches

In the History of the Royal Astonomical Society, where there is a write up of the proceedings, (but no reference quoted), the second clause continues:

‘... in different geographical regions, and at different altitudes. In these purposes India and the Colonies offer peculiar advantages.’

This proposed ammendnment complete with the additional section is also quoted by AJ Meadows in his book Science and Controversy. The reference Meadows gives appears to be a document he found in the Lockyer archives at sidmouth which he describes as ‘Royal Astronomical Society Circular 21 June 1872’.

1872, June 28, RAS council meets

The following 15 people were present:

Cayley* (in the chair), De la Rue* (vice-president), Huggins*, Whitbread, Dunkin (Assistant at Royal Observatory & Secretary to the Society), Proctor, Strange (foreign secretary), Airy (Astronomer Royal), Browning, Burr, Buckingham, Christie (Chief Assistant at Royal Observatory), Knott, Lockyer & Ranyard.

The ammendment put forward by Strange at the meeting on 21 June was negatived as was a further ammendment proposed by De la Rue and seconded by Whitbread that:

The Council recommend that a proper provision be made in England for conducting the above researches within the Greenwich Observatory

It was then agreed to stick with the original three clauses agreed on 21 June.

Following the meeting, De la Rue, Strange and Lockyer all resigned from the RAS Council. According to the rough minutes of the next meeting (which wasn’t until 8 November), De la Rue and Strange sent their resignation letters to Cayley (the President) whilst Lockyer sent his to Dunkin (one of the two Secretaries). De la Rue continued however to serve on the Observatory’s Board of Visitors. Although the letters no longer appear to exist, they seem to have been available to Hollis who wrote the relevant section of the the History of the Royal Astonomical Society which was published in 1923. According to Hollis, De la Rue resigned

‘because he felt "that the opinion of the majority had diverged considerably from his own on various occasions" ; Colonel Strange, because he thought that certain members of the Council were incompetent and that these exercised an undue influence; and Mr. Lockyer, because Mr. Proctor made repeated attacks on him in "certain obscure prints," and for this reason he did not wish to sit at the Council table with him.’

1872, July 2. Cayley (as President of the RAS) submits written communciation to the Royal Commission.

Cayley declined to give evidence, but his communication contained a copy of a resolution passed by the RAS council on 28 June.

The Resolution (as published by the Commission):

1. That the President be authorised, on behalf of the Council and Fellows of the Royal Astronomical Society, to bring before the Royal Commissioners on Scientific Instruction and on the Advancement of Science, now sitting, the importance of further aid being afforded to the Cultivation of the Physics of Astronomy.

2. The Council think such aid would be most effectually given by increased assistance, where needed, to existing Public Observatories, in the direction recommended by the Heads of those Observatories, especially that at the Cape of Good Hope, and by the Establishment of a new Observatory on the Highlands of India, or in some other part of the British Dominions where the climate is favourable for the use of large instruments.

3. The Council do not recommend the Establishment of an independent Government Observatory for the Cultivation of Astronomical Physics in England, especially as they have been informed that the Board of Visitors of the Royal Observatory of Greenwich, at their recent meeting, recommended the taking of photographic and spectroscopic records of the sun at that Observatory.

Click here to read in the original format. The Council informed the Society of the resolution at its Annual General Meeting on 14 February 1873 (click here to read). Note the minor differences that exist not only between these two versions, but also the slight differences between them and the version signed off in the Council minutes (above).

1872, July 12. De la Rue gives evidence to the Royal Commission. Click here to read.

1872, July 31. Airy wrote to the Admiralty about the Visitors’ proposal (RGO6/26)

The Admiralty agreed to the propsal, providing funds in the Navy Estimates for one additional assistant at the start of the new financial year (1 April 1873) together with £210 for the building and equipping of a room for photographic and spectroscopic observations. Formal plans were also put in place to borrow the Kew Photoheliograph.

1872, Nov 1. Strange submits written communciation to the Royal Comission. Click here to read.

1874. Volume II of the Royal Commission Report published (containing the evidence detailed above).

1875. Duke of Devonshire joins the Board of Visitors.

The photoheliographs

3½-inch Kew Photoheliograph (1854)

4-inch Dallmeyer Photoheliographs – five in total (1873)

Thompson 9-inch Photoheliograph (c.1888/1891)

The photographic process

... to be continued.

Measuring the photographic plates

... to be continued.

Officers in Charge / Heads of Department

1873–1913 E Walter Maunder (retired Nov 1913)

1913–1916 Walter Bryant

1916–1919 E Walter Maunder (returned to provide cover during the war)

1919–1955 Harold Newton

1955–1975? Philip Laurie

Published Observations

The observations were published as follows:

1874–1955 Annual volumes of Greenwich Observations

1956 Royal Observatory Greenwich Bulletins

Nos: 14 (1956),

1957–1961 Royal Observatory Bulletins

Nos: 26 (1957), 57 (1958), 103 (1959), 132 (1960) & 144 (1961)

1962–1976 Royal Observatory Annals

Nos: 6 (1962–64), 8 (1965), 10 (1966), 11 (1967), 12 (1968–71) & 13 (1972–76)

Digitised copies of the published observations

Digitised copies for all the above are available to download from UK Solar System Data Centre (registration (but no subscription) required). Click here to read more about the organisation and publication of the Greenwich results.

Further Reading

The Greenwich Photo-heliographic Results (1874 – 1976): Summary of the Observations, Applications, Datasets, Definitions and Errors. D. M. Willis, H. E. Coffey, R. Henwood, E. H. Erwin, D. V. Hoyt, M. N. Wild & W. F. Denig. Sol Phys (2013)

The Greenwich Photo-heliographic Results (1874 – 1885): Observing Telescopes, Photographic Processes, and Solar Images. D. M. Willis, M. N. Wild, G. M. Appleby & L. T. Macdonald. Sol Phys (2016)

Re-examination of the Daily Number of Sunspot Groups for the Royal Observatory, Greenwich (1874 – 1885). D. M. Willis, M. N. Wild & J. S. Warburton. Sol Phys (2016)

© 2014 – 2025 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan