…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

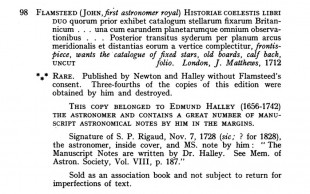

Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis and the etchings of Francis Place – a comparative study

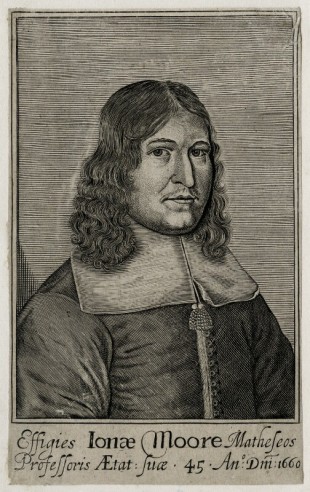

Jonas Moore after an unknown artist. Frontispiece to Moore's Arithmetick (1660). Line engraving © National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license (see below)

Although the drawings are now thought lost, contemporary etchings made from them by Francis Place survive in small numbers. In the preface to the 1725 edition of his Historia Coelestis (Vol 3, p.102), Flamsteed records that the etchings were prepared at the expense of Sir Jonas Moore who ‘kindly bestowed’ them on him. Moore, who died in 1679, was Surveyor General of the Ordnance, a fellow of the Royal Society and one of the chief instigators for Flamsteed’s appointment as Astronomer Royal. Having already given Flamsteed a micrometer by Towneley in 1670, Moore commissioned and personally paid for the all the new instruments constructed for use at Greenwich. Donated to Flamsteed personally, rather than to the Observatory, they included a 10-foot Mural Quadrant, a 7-foot Equatorial Sextant and clocks by Thomas Thompion, all of which appear in the etchings.

Of the twelve known etchings, only one (the Title Plate) bears the names of Thacker and Place. None are dated. Together, they form a hugely important visual record not only of the Observatory in its earliest days, but also of Greenwich Park following its relandscaping in the 1660s. None of the printing plates are known to survive and most of the etchings survive only in very small numbers. Although the exact date of the etchings is unknown, it would appear that both the drawings and the etched plates were created at some point following the erection of the 60-foot mast telescope in the summer/autumn of 1677 (it appears in seven of the images) and the death of Jonas Moore in August 1679.

Five of the plates are annotated with letters for use with a key, suggesting that they were originally prepared, at least in part, to illustrate the results of Flamsteed’s work in some future volume and to send to other astronomers with whom he was corresponding.

Although there is no documentary evidence to prove the claim, in The Nature of the Book (1998), Adrian Johns states that the Francis Place etchings were commissioned ‘in imitation of Tycho’s Astronomiæ instauratæ mechanica’ which was first published in 1598 and that Flamsteed planned to model his Historia Cœlestis Britannica on Tycho’s Historia Cœlestis Danica. Frances Willmoth, on the other hand, notes instead in her Intoduction to Volume 1 of Flamsteed’s Correspondence (1995), that the etchings are similar in conception to some of those in Volume 1 of Machina coelestis pars prior which had recently been published by Hevelius in 1673. Particularly striking, when comparing the Place etchings with those of Hevelius are the similarites of the images of the mast telescopes and the darkened room for observing sunspots and solar eclipses. Indeed, Place Plate 10a is almost a mirror image of Hevelius’s fig. 5. Hevelius is known to have modelled his publications on the earlier ones of Tycho. Although the Place etchings are more similar in style to those published by Hevelius, this is perhaps unsurprising, as when Tycho observed the telescope had not yet been invented.

Interestingly, Flamsteed did not specifially mention the etchings in his ‘An estimate of the number of folio pages that the Historia Britannica Coelestis, may contain when printed’ (RS/EL/F1/130 – the Royal Society also has a printed copy dated 8 Nov. 1704; more on this below). This may however have been because he intended to include them as part of the preface whose size he was unable to estimate at that time. As things turned out, none of the etchings were included in the Historia published in 1712 under the revised title of Historiae Coelestis Libri Duo (which consisted of two books published as one) and only one (Plate 11 in the list below), was included in his Historia(e) Coelestis Britannica which was published posthumously in three volumes in 1725.

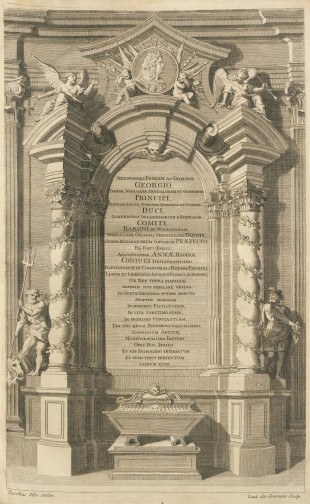

Frontispiece to the 1712 Historia, Engraved by George Vertue after Juan Batista Catenaro. Disbound and trimmed (325x208mm). Portrait of Prince George of Denmark, in oval flanked by allegorical figures and supported by an eagle; in the upper part, some putti unfurling a banner bearing the title; below, at right, a bowing Neptune, at left a river god. Later inscription of 'George Prince of Denmark' at bottom centre

Following the death of both the Queen in 1714 and Newton’s patron, the Earl of Halifax, in 1715, Flamsteed was able to acquire 300 of the 400 copies that had been printed. After extracting, for reuse, only those pages that had been printed by the end of 1707, Flamsteed burnt the rest (which included the catalogue of fixed stars, Stellarum Fixarum Catologus Britannicus, from Book 1 and the whole of Book 2). Writing to his former Assistant Abraham Sharp on 29 March 1716 before he did so, Flamsteed explained he was destroying them so

‘that I may hinder any more false Catalogues from going abroad of his [Halley’s] very sorry abstracts which I intend to Sacrifice to TRUTH as soone as I can get leasur saveing some few that I intend to bestow on you and such freinds as you that are herty lovers of truth that you may keep them by you as Evidences of the malice of Godless persons and of the Candor and sincerity of the freind that writes to you, and conveys them into [your] hands.’ (Flamsteed Correspondence, Vol 3, p.785 also in Baily’s An Account of John Flamsteed p.321)

Writing to Sharp on 8 May 1716, Flamsteed informed him:

‘I shall take up [to London] with me copys of the corrupte[d] Catalogue etc to be stitcht up for you and some few freinds and I hope the week after to leave one with the Carrier for you directed as you order. I Committed them to the fire about a fortninght agone If Sir I.N. would be sensible of it I have done both him and Dr Hally a great kindnesse’. (Correspondence Volume 3, p.789 and Baily p.322)

The volume, ‘bound in calves leathe rough’ was sent to Sharp at the end of May, Flamsteed informing him later that

‘all the faults are marked in it with lines under them the stars that are false placed are marked in the Margent whe[n] you compare them with my own catalogue ... you may perhaps find more errors than I have noted, if you doe pray keep a list of them and let me have a copy of it in good time’ (Correspondence Volume 3, p.795 and Baily p.322)

Several of these corrupted or ‘imperfect’ copies, as they were later described by Baily, still exist. Three copies are known that had etchings bound into them before they were sent to their recipients (two with nine and one with three). Whether they were put together in 1716 like the one for Sharp, or whether they were put together during the following decade is not known. Details of the the contents of these volumes are given below.

Although none of the etchings were distributed via the Historia until at least 40 years after the Observatory had been founded, sets had been given away as presents by Flamsteed (and possibly Moore) starting at a date no later than January 1680. In a letter to Towneley, dated 14 January 1679/80, Flamsteed wrote ‘I have procured two setts of prospects of the Observatory for him [Towneley’s brother]’. These, as we learn from a later letter to Towneley, dated 13 February, were destined not for Towneley’s brother, (who was living in Paris at the time), but for him to pass on to Roemer and Cassini (Flamsteed Correspondence, Volume 1, p.724 & 733).

Another set was sent to Hevelius in 1682. In a letter dated 19 September, Flamsteed wrote (translation from the Latin):

‘Along with these [some calculated distances made with the sextant] I have sent you various views of the Observatory with the illustrations of the instruments which in your letter to Mr Halley you have previously asked him to procure for you: later indeed than I would have wished, because I have not had them in my control until very recently.’ (Flamsteed Correspondence, Volume 2, p.40)

This, together with the earlier letter Flamsteed sent ot Towneley, implies that possession of the printing plates was retained first by Moore (who died intestate) and then his son (also called Jonas) who died in 1682. It seems at this point the printing plates, passed into Flamsteed’s hands.

On the same day that Flamsteed wrote to Helvelius, he also wrote to Johann Zimmerman (also in Latin) enclosing a ‘picture’ of the sextant ‘together with several views of the Observatory’ (Flamsteed Correspondence, Volume 2, p.42). In the surviving correspondence there are relatively few references to sets of the etchings being given away by Flamsteed. Apart from the four sets mentioned above, the only other reference comes in a letter sent to Flamsteed dated 22 December 1685 (Flamsteed Correspondence, Volume 2, p.268).

Nowhere in the published Correspondence is there any indication of the number of images Flamsteed sent on each occasion. The wording used at different times does however suggest that different recipients received different selections.

List of plates

The etchings do not themselves carry any form of numbering. For convenience, the plate numbers used here are the same as those used by Derek Howse in his 1975 book, Francis Place and the Early History of the Greenwich Observatory. The numbering is based on the sequence that the prints were entered in the British Museum register when it acquired a partial set of the prints in 1865. A similar sequencing was used more recently by the Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives when cataloguing their collection. Plates 10, 11 and 12 each contain two different images which Howse labelled (a) and (b).

No. |

Title |

Translation |

||

| 1 | Vivarium Grenovicianum ... |

Greenwich Park [Title Plate] |

||

| 2 | [none given] |

[Map of Greenwich Park] | ||

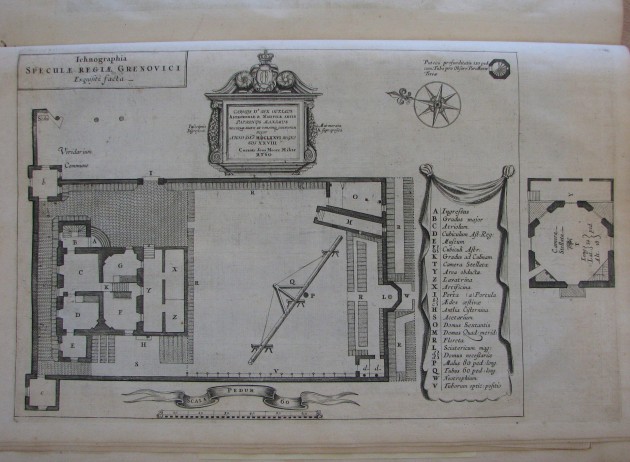

| 3 | Ichnographia Speculae Regiae ... |

Plan of the Royal Observatory Greenwich |

||

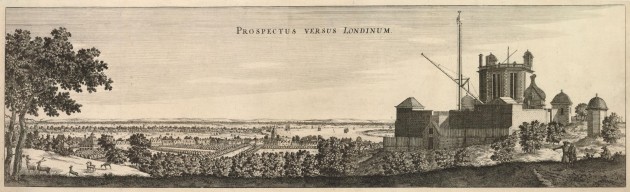

| 4 | Prospectus versus Londinium | Prospect towards London | ||

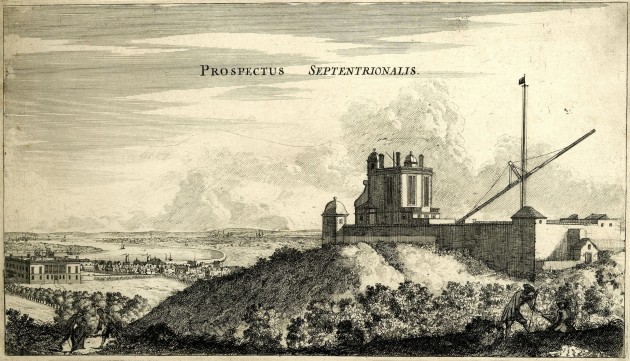

| 5 | Prospectus Septentrionalis |

North prospect |

||

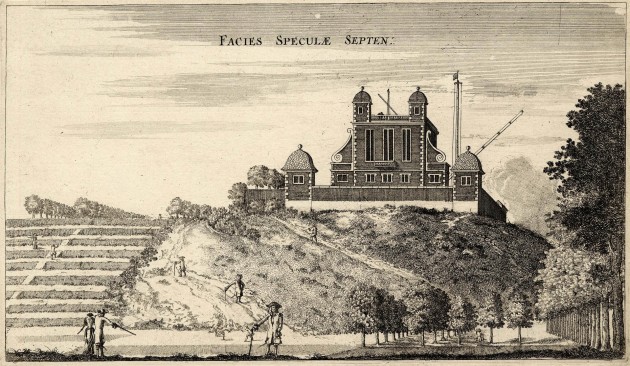

| 6 | Facies Speculae Septen |

North face of the Observatory |

||

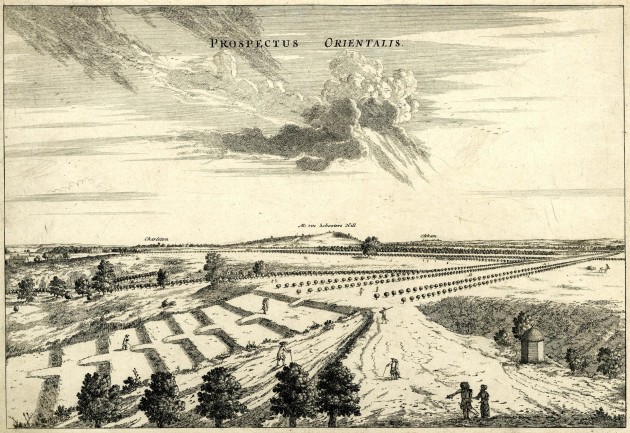

| 7 | Prospectus Orientalis |

East Prospect [from the Observatory] | ||

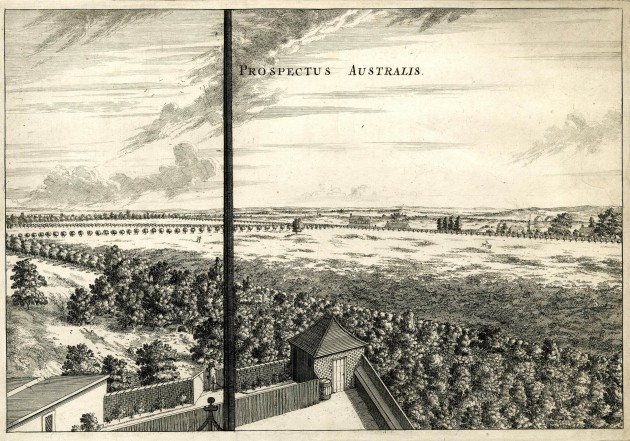

| 8 | Prospectus Australis |

South Prospect [from the Observatory] |

||

| 9 | Prospectus intra Cameram Stellatam |

Prospect within the Star Chamber [Octagon Room] |

||

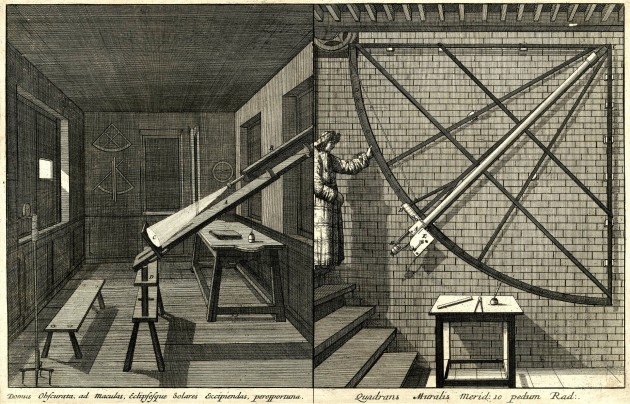

| 10 |

a | Domus Obscurata ... |

Darkened House [Summerhouse interior] |

|

| b | Quadrans Muralis Merid: ... | Meridian mural quadrant [Hooke’s] | ||

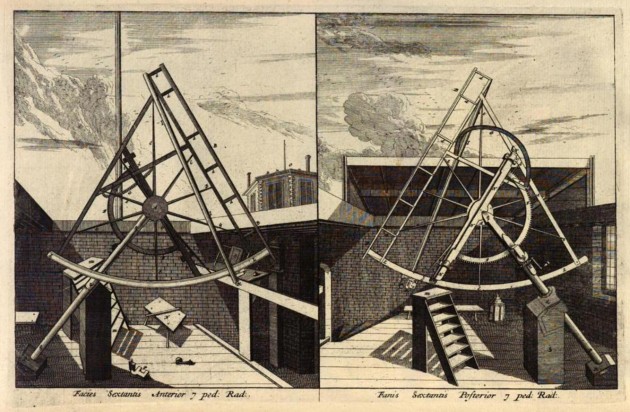

| 11 | a | Facies Sextantis Anterior ... |

Front aspect of the sextant |

|

| b | Fanis Sextantis Posterior ... | Rear aspect of the sextant | ||

| 12 | a | Petus 100 pedum ... |

Well of 100 feet [Flamsteed’s Well Telescope] | |

| b | Partes Instrumentorium ... | Parts of instruments |

At least six organisations hold significant numbers of the etchings. They are:

Pepys Library, Magdalene College Cambridge

Royal Society of London

Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives

Greenwich Heritage Centre

British Museum

Society of Antiquaries of London

The Francis Place etchings reproduced in whole and in part on this page have been digitised from copies held in the collections of: the British Museum, Greenwich Heritage Centre, Lyon Public Library, the Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives and the British Library. The digital images from the British Museum are © The Trustees of the British Museum and are reproduced under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license, full details of which are given at the bottom of the page.

The dimensions given by Howse are ‘generally of the plate itself, [but] sometimes of the boarders’. Those given in the Pepys catalogue are assumed to be the actual print size. Those given by Hake are taken from the etchings in the possession of the British Museum.

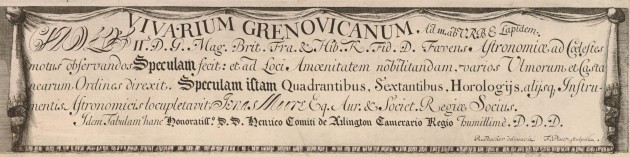

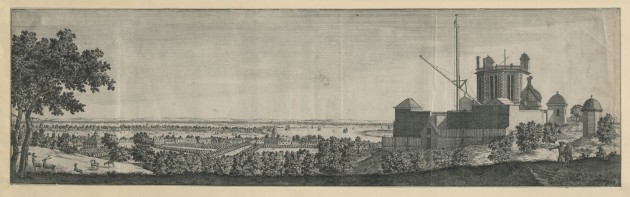

Vivarium Grenovicianum, Greenwich Park (Howse Plate 1)

Vivarium Grenovicianum. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.946

Dimensions: Howse: 101x440 mm (Boarders). Pepys: 101x440 mm. British Museum: 112x446 mm. Hake: 103x444 (Plate Line). Catalogued by the British Museum as an engraving.

The text text translates as:

‘Greenwich Park, Three miles from the city. Charles II by the grace of God King of Great Britain, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, as the Patron of Astronomy built the Observatory to observe the movements of the heavens: and to enrich the beauty of the place, he planted various rows of elm and chestnut trees. Sir Jonas Moore, Fellow of the Royal Society, equipped this observatory with quadrants, sextants, clocks and other astronomical instruments. He humbly donated and dedicated this tablet to the Honourable D.D. Henry, Earl of Arlingcourt, Royal Chamberlain. Drawn by Robert Thacker, engraved by Francis Place.’ (Howse, Francis Place (1975))

Although the image as reproduced here and on the British Museum website has been clipped on the left hand edge, the etching itself is known to have margins that extend into the plate mark if not beyond.

Reproduced in:

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975), p.31.

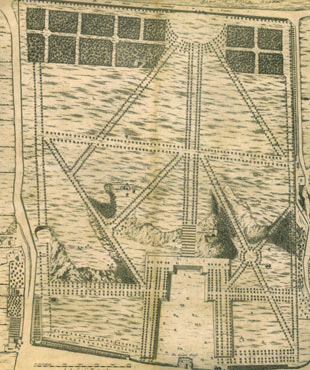

Map of Greenwich Park (Howse Plate 2)

Only two copies of this etching are known. One is held by the Pepys Library. The other was discovered by Howse in the collections of the Greenwich Local History Library (which was later merged with the Borough Museum to form the Greenwich Heritage Centre).Dimensions: Howse: 523x453 mm. Pepys: 523x453 mm.

The scale information on the map is incorrect and should read ‘Scale of ‘Yards’, not ‘Scale of ‘Feet’. The copy at the Greenwich Heritage Centre has a handwritten correction.

In the past, there appears to have been some doubt as to whether this map was actually part of the set. The reasons for believing it to be so are set out below:

Writing to Abraham Sharp on 21 April 1721, Joseph Crossthwait asked

‘I should be glad to know whether you had ever the map of Greenwich Park, the plan of the Observatory, with the different prospects of it, sent: if you have not, I will send them, as soon as some few alterations are made in the plate of the Park.’ (Baily p.343)

In the Pepys collection (which was mounted in an album in 1700) the Map and Title Plate are glued into an album with the Title Plate glued onto the rear of the folded in section of the map. The catalogue entry states ‘Letters and references to items (on curtain) to r.’ Given the heading on the Title Plate is ‘Greenwich Park’, it is not unreasonable for the set to have had a map showing the location of the Observatory within it. Taken with the evidence of Crossthwait’s letter, there is every reason to suppose that the map is genuinely part of the same set of etchings by Place. .

Howse speculated that the Title Plate and the map may have been etched on the same physical plate because of their very similar widths. If they were, it might also explain why there are so few known copies of the Title Plate. It would also explain why the map itself does not have a title inscribed on it. Howse was also of the view that there is a similarity of styles between the map, the plan and the views. There are definite similarities between the fonts used on both the map and some of those used on the Title Plate as well as with the font used on Plates 10–12.

Pepys Library copy reproduced in:

- John Bold, Greenwich (2000), Fig.14, p.10. Top third is cropped

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975). Cropped on all edges.

Greenwich Heritage Centre copy reproduced in:

- D Jacques and A J van der Horst, The Gardens of William and Mary (1988), p.22. Credited as Land Use Consultants. Trimmed to border of the map.

Copy of uncertain origin reproduced in:

- The Royal Parks, Greenwich Park Conservation Plan 2019–2019, p.39. Trimmed to the Park Boundary, which is irregular in shape. Image not credited. Download as pdf.

Ichnographia Speculae Regiae, Plan of the Royal Observatory Greenwich (Howse Plate 3)

Iconographia Speculae Regiae Grenovici Exquisitè facta. Reproduced by kind permission of Greenwich Heritage Centre from their 'imperfect' copy of Historiae Coelestis Libri Duo

Dimensions: Howse: 225x360 mm. Pepys: 215x354 mm. Recorded in the Pepys catalogue as an engraving.

The plan shows the ground floor (left) and the upper floor (right). The basement floor is not shown. The layout seems strange as the left and right edges go right to the edge of the plate mark. In addition, the upper floor, the Camera Stellata (Octagon Room), is outside the boarder and has been rotated 90 degrees in an anticlockwise direction relative to the ground floor. According to the inscription on the plan of the Observatory the Octagon Room was 34 feet long and 34 feet wide and 18 feet high, though it is not specified if 18 feet was the distance from the floor to the top of the wall or the top of the domed ceiling, nor where the 34 feet was measured from. It would appear that either the the figure of 34 feet is incorrect or it includes the thickness of the walls!

The Well Telescope is also shown in the wrong location. For more information on this, see Flamsteed’s Well Telescope. Although the Well Telescope (top right) is described on the plan as being 120 feet deep, its depth on Plate 12 is given as 100 feet.

Key: (A) Entrance, (B) Great stairs, (C) Small hall, (D) Astronomer Royal’s bedroom, (E) Study, (F & G) Astronomer’s rooms, (K) Stairs to Kitchen, (T) Star Chamber [Octagon Room], (Y) Covered area, (Z) Washplace, (X) Workshop, (I) Gate, (a) Small gate, (b & c) Summer houses, (H) Pump for Cistern, (S) Vegetable Garden, (O) Sextant House, (M) Meridian Quadrant House, (R) Flower Garden, (L) Large Sundial, (d & d) The Necessaries [toilets], (P) Mast 80 ft long, (Q) Tube 60 ft long, (W) Nursery [Potting Shed], (V) Position of optical tube, (T) Genoa Pan (portable heating stove).

The tablet (top centre) depicts the tablet that remains in place over the original front door to Flamsteed House ((A) on the plan). The text translates as:

‘Charles II, Gracious King, Greatest Patron of the Arts of Astronomy and Navigation built this observatory for the advantage of both these Arts in the year of our Lord 1676 In the 28th Year of his Reign Keeper, Jonas Moore, Knight, Surveyor General to the Ordnance’

Reproduced in:

- Adrian Johns, The Nature of the book (1998), p.552. Right margin cropped

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975), p.35

- Philip Laurie, The Old Royal Observatory (1960), op. p.7. Reproduced without the Camera Stellata. Click here to view.

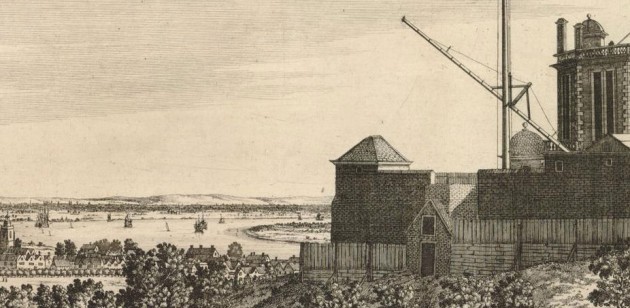

Prospectus versus Londinium , Prospect towards London (Howse Plate 4)

Prospectus versus Londinium © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.947

Dimensions: Howse: 196x618 mm. Pepys: 170x593 mm. British Museum: 198x610 mm. Hake: 174x596 (Border Line). British Library: 175x599 mm (trimmed within plate mark).

Apart from the Observatory itself, the following should be noted. The Well Telescope (extreme right). The two mast telescopes, one in the garden, the other on the roof of the Octagon Room. St Alphage Church, Greenwich before it was rebuilt following its partial destruction during a storm in 1710 (centre). The building with the belvedere on top (extreme left), which was owned by a Mr Cottle and appears in several historic views.

Reproduced in:

- Clive Aslet, The Story of Greenwich (1999), p.118 & 190. Digitally cleaned with loss of detail in sky. Margins cropped

- Adrian Johns, The Nature of the book (1998), p.580. Digitally cleaned with loss of detail in sky. Margins cropped

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975), p.36–37. Partially cleaned. Margins very slightly cropped

- Derek Howse, Greenwich Observatory (1975), Fig 5. Shows only the right half with the Royal Observatory

- Philip Laurie, The Old Royal Observatory (1960), cover illustration. Cleaned with loss of detail in sky. Margins very slightly cropped.

- Thankfull Sturdee, Royal Observatory, Greenwich, Black and White Budget, (1901) , p.788. Shows only the right half with the Royal Observatory

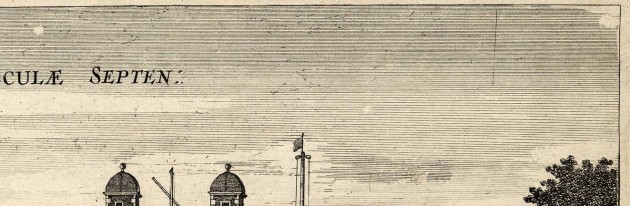

Prospectus Septentrionalis, North Prospect (Howse Plate 5)

Prospectus Septentrionalis © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.948

Dimensions: Howse: 174x302 mm. Pepys: 168x296 mm. British Museum: 172x302 mm. British Museum (Crace copy) 167x297 mm (trimmed). Hake: 169x298 (Border Line).

The Queen’s House (extreme left) where Flamsteed resided during the construction of the Observatory is now in the care of the National Maritime Museum. Also visible are Crowley House (the first building on the banks of the Thames when coming from the right), whose construction began in 1647 and which was acquired in 1704 by Sir Ambrose Crowley. Demolished in 1855, the site was later used for a tramway depot and is now occupied by Greenwich Power Station. To its left are the buildings of Trinity Hospital, which dates from 1613 and still survives. It was originally known as Norfolk College.

Reproduced in:

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975), p.41. Margins cropped

- Harold Spencer Jones, The Royal Observatory, Greenwich (1943, 1944,1946, 1948), op, p.13. Margins cropped

- E.Walter Maunder, The Royal Observatory Greenwich (1900),op, p.45. Margins cropped. Click here to view.

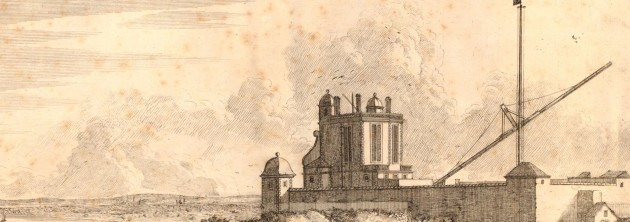

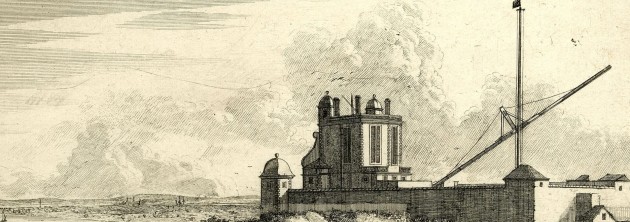

Facies Speculae Septen, The north face of the Observatory (Howse Plate 6)

Facies Speculae Septen. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.949

Dimensions: Howse: 177x299 mm. Pepys: 170x294 mm. British Museum: 174x301 mm. Hake: 170x296 (Border Line).

The 1660s were a hive of activity in and around Greenwich Park. In 1661, King Charles II ordered the demolition of the derelict Tudor Palace at Greenwich. John Webb was commissioned to design a new one and repair and enlarge the Queen’s House. Work started on the Queen’s House in August 1661 and on constructing the new Palace (now the Old Royal Naval College) in 1663. In 1661, work also began on re-landscaping the Park. The following year, Pepys recorded in his diary entry of 11 April:

‘At Woolwich, up and down to do the same business; and so back to Greenwich by water, and there while something is dressing for our dinner, Sir William [Penn] and I walked into the Park, where the King hath planted trees and made steps in the hill up to the Castle, which is very magnificent.’

Likewise, William Schellinks recorded the arrival of the steps in his journal, recording in the entry for 25 October 1662:

‘On the hill in the park behind the [Queen’s] house two avenues of trees had been planted from the bottom to near the top of the hill, where it was too steep to climb up, steps had been cut into the ground to walk up in comfort.’

The steps that both Pepys and Schellinks referred to were a series of grass terraces or ‘ascents’ which later became know as the ‘Giant Steps’. They can be seen on the left in the etching.

In May 1662, the Frenchman André Le Nôtre was asked to contribute to the designs for the Park and it was he who came up with the plan for the Parterre, which occupied the more level ground between the Queen’s House and the bottom of the Giant Steps. It was bordered on either side by banks and rows of newly planted trees, some of which can be also be seen (bottom right).

By the start of the twenty-first century, although much eroded, traces of the Giant Steps (possibly recut in the early eighteenth century) were still visible as was the outline of the Parterre; which was still demarked by rows of trees – albeit not those originally planted. In 1964, a report titled Trees in Greenwich Park from the Advisory Committee on Forestry produced for the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works (which was responsible for the Park until 1970) made a series of recommendations that included the restoration of the Giant Steps. Most of the recommendations were however ignored at that time. In 2020, the Park secured a grant of £4,517,300 from the Heritage Lottery fund towards the cost of improving the Park and restoring some of the seventeenth century features, including the Giant Steps and aspects of the Parterre. This etching, together with Plates 2 and 7 was crucial in the formulation of those plans.

Reproduced in:

- John Bold, Greenwich (2000), Fig 15, p.10. Margins cropped

- Clive Aslet, The Story of Greenwich (1999), p.138. Margins cropped

- Adrian Johns, The Nature of the book (1998), p.552. Top half and lower margin only (due to an editing error)

- Frances Willmoth, Sir Jonas Moore (1993), p181

- Science and Engineering Research Council, Royal Greenwich Observatory: Telescopes, Instruments, Research and Services, October 1, 1980-September 30, 1985, p.106

- Allan Chapman, The Preface to John Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis Britannica (1982), Fig.12, p.114. Margins cropped

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975), p.43. Margins cropped

- Derek Howse, Greenwich Observatory (1975), fig 4. Margins cropped

- Ed. Colin A. Ronan Greenwich Observatory 300 years of Astronomy (1975), p.12. Margins cropped

- Olive & Nigel Hamilton. Royal Greenwich (1969), p.229. Margins cropped

- Harold Spencer Jones, The Royal Observatory, Greenwich (1943, 1944,1946, 1948)

- The Walpole Society, X (1921–2), pl.LXXXVa

- Various guides to the Royal Observatory published on behalf of the National Maritime Museum and the Royal Greenwich Observatory, Herstmonceux. Of particular note is the guide The Royal Observatory, The Story of Astronomy & Time (c.1990), ISBN 0-948065-05-02, in which the etching is reproduced uncropped, with the whole of the plate mark visible. NMM Neg. No. 7228.

Prospectus Orientalis, East Prospect (Howse Plate 7)

Prospectus Orientalis. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.950

Dimensions: Howse: 218x316 mm. Pepys: 203x298 mm. British Museum: 210x306 mm. Hake: 204x301 (Border Line).

In this view from the top of Flamsteed House, the Giant Steps (left), lead up to Blackheath Avenue with its recently planted double rows of trees on either side. To the right is the small building located outside the walled enclosure of the Observatory that housed Flamsteed’s Well Telescope.

Reproduced in:

- John Bold, Greenwich (2000), Fig.17, p.11. Margins cropped

- Clive Aslet, The Story of Greenwich (1999), p.113. Margins cropped

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975), p.45. Margins very slightly cropped.

Prospectus Australis, South Prospect (Howse Plate 8)

Prospectus Australis. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.951

Dimensions: Howse: 216x318 mm. Pepys: 202x298 mm. British Museum: 215x310 mm. Hake: 205x301 (Border Line).

In this second view from the top of Flamsteed House, the thick vertical line near the centre is the mast used to support the 60-foot telescope. To its left, is the Quadrant House and to the right, the Necessary House (toilet). The avenue of trees running from centre left to bottom right was known at the time as Snow Hill Walk.The figure immediately to the left of the mast is standing by a sundial. Just above him and a little to the left is an intriguing structure which was first noted in modern times on Dominic Clinton’s blog Subterranean Greenwich and Kent.

Airy marked a structure in about this position on the two plans of the observatory he published in 1847 and 1863 and described it as ‘An ice-house belonging to the Ranger’s House’. What appears to be the entance also appears as a rectangle on a sketch plan made by Airy in 1836, where it is described as a fountain. A rectangular structure also appears in the same position on the series of site plans published in 1885, 1891, 1896, 1905 and 1911, though its function is not marked. A similar marking appears in the same position on various large scale Ordnance Survey Maps.

The structure in the etching may turn out to be the entrance to the snow conserve, (also referred to as a snow-house or ice-house), constructed for King James I in about 1620.

Reproduced in:

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975), p.47.

Prospectus Intra Cameram Stellatam, Prospect within the Star Chamber (Howse Plate 9)

Prospectus Intra Cameram Stellatam. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.952

Dimensions: Howse: 220x302 mm. Pepys: 211x295 mm. British Museum: 219x302 mm. Hake: 213x298 (Border Line).

In the early 1990s, the Cameram Stellatam (now known as the Octagon Room on account of its eight sides), was restored to give it much the same appearance as it has here. The left-hand window faces the north and the right-hand window the east. Over the years, the main alterations to the room were to the windows which were altered for Maskelyne in 1779 and again in the late 1700s when sash windows were inserted. Of these, the North facing window was replaced by one of plate glass by Airy in the mid 1850s. The present windows, which are similar in design to the originals, were installed during renovation work in the early 1950s and originally had glass that was mainly opaque. After an outcry in the press, this was soon replaced by the clear glass that can be seen today. The floor perspective is problematic.

Key: (A) & (B) The two year going Tompion Clocks presented to Flamsteed by Sir Jonas Moore. (C) A further clock about which little is known. (D) 3-foot moveable quadrant. (F) Stand for supporting the eye-end of a telescope tube with a screw mechanism for adjusting its height (S) Ladder for supporting the object-glass end of a telescope tube. (T) 8½-foot telescope tube.

Of the various instruments and pieces of equipment, only the two Tompion Clocks still survive (though in an altered state). The doorway in the centre, leads to the stairs down to the floor below. The portraits above the door are of King Charles II and James Duke of York (later James II).

Reproduced in:

- John Bold, Greenwich (2000), Fig.34, p.23. Margins cropped

- Clive Aslet, The Story of Greenwich (1999), p.136. Margins cropped

- Fracis Willmoth (ed), Flamsteed’s Stars (1997)

- Frances Willmoth, Sir Jonas Moore (1993), p185

- Allan Chapman, The Preface to John Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis Britannica (1982), Fig.13, p.114. Margins cropped

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975), p.47. Margins cropped

- Derek Howse, Greenwich Observatory (1975), fig 2. Margins cropped

- Ed. Colin A. Ronan Greenwich Observatory 300 years of Astronomy (1975), p.14. Margins cropped

- Olive & Nigel Hamilton. Royal Greenwich (1969), p.55. Margins cropped

- Royal Greenwich Observatory official Christmas Card (1951)

- The Wren Society, XIX (1942), pl.LXVIII

- W. Douglas Caroe, Sir Christopher Wren and Tom Tower, Oxford (1923)

- E.Walter Maunder, The Royal Observatory Greenwich (1900) op, p.52. Margins cropped. Click here to view

- John Richard Green, A short history of the English people, Vol 3 (1894) p.1302

- Various guides to the Royal Observatory published on behalf of the National Maritime Museum and the Royal Greenwich Observatory, Herstmonceux (Margins both cropped and uncropped).

Other digitised copies of the etching:

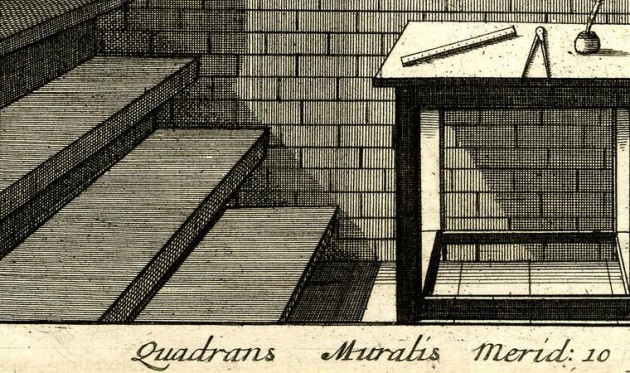

(A) Domus Obscurata ..., Darkened House. (B) Quadrans Muralis Merid: ..., Meridian mural quadrant (Howse Plates 10a and 10b)

(A) Domus Obscurata, Ad Maculas, Eclipsesque Solares Excipiendas, Peropportuna, (B) Quadrans Muralis Merid: 10 Pedum Rad:. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.953

Dimensions: Howse: 200x310 mm. Pepys: 193x298 mm (including lettering). British Museum: 195x305 mm. Hake: 185x299 (Border Line).

The full text of the titles of the two images translates as: (Left) Darkened House, very comfortable for receiving sunspots and solar eclipses, (Right) Meridian mural quadrant: 10-foot Radius.

The left image (10a) shows the interior of the ground floor of the eastern summerhouse (labelled (b) in the plan depicted in Plate 3 above). The viewpoint is from the west. The telescope is pointing towards one of the two windows on the room’s southern wall.

Key: (A) Adjustable support for he telescope and screen. (B) 2-foot telescope for projecting the Sun’s image. (C) Screen onto which the image was projected. (D) Adjustable stand, similar in design to that in the Octagon Room in Plate 9 above.

The right image (10b) shows Hooke’s 10-foot Mural Quadrant, an instrument that proved unsuccessful and was abandoned by Flamsteed in 1677.

Key: (A) Moveable index containing crosswires. (B) Eyepiece. (C) Pivot at the centre of the circle of which the Quadrant formed a part to which the telescope was attached. (D) Subsidiary arc. The limb of the Quadrant was only marked at intervals of 5o. The purpose of the subsidiary arc, which was divided into smaller divisions was to allow smaller intervals to be measured by aligning it with the marks on the Quadrant. (E) A crank for moving (A).

A close up of the index of Hooke’s 10-foot Mural Quadrant was included in Plate 12.

Reproduced in:

- Frances Willmoth, Sir Jonas Moore (1993), p189. Plate 10b only

- Allan Chapman, The Preface to John Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis Britannica (1982), Fig.18, p.119. Plate10b only

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975), p.51 & 53. 10a and 10b printed separately

- Derek Howse, Greenwich Observatory (1975), Fig.19 (10b only), Fig.102 (10a only)

- Olive & Nigel Hamilton. Royal Greenwich (1969), p.59 (10b only, Margins cropped

- The Wren Society, XIX (1942), pl.LXIX

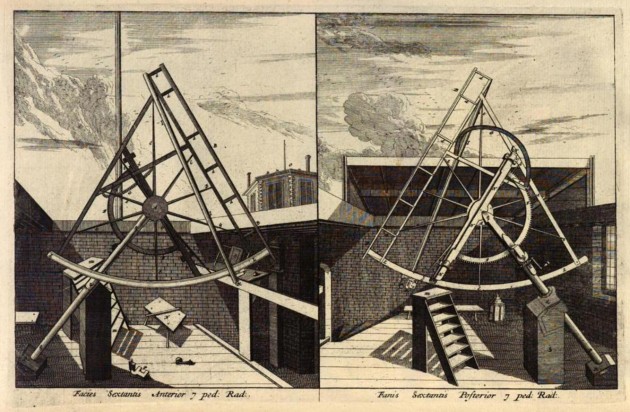

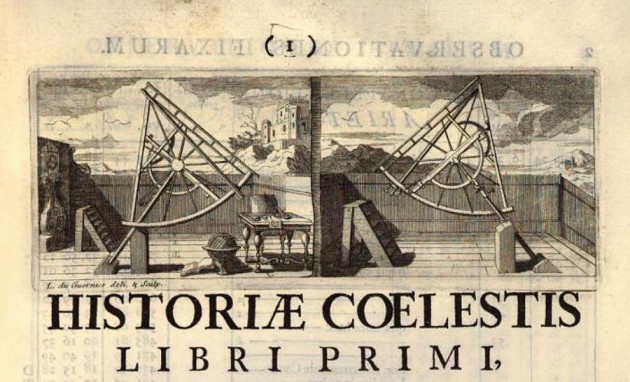

Facies Sextantis, Apearance of the Sextant (Howse Plates 11a and 11 b)

(A) Facies Sextantis Anterior 7 Ped: Rad: (B) Fanis Sextantis Posterior 7 Ped: Rad:. From the copy of Volume 1 of Flamsteed's Historia Coelestis Britannica (1725) in Lyon Public Library. Digitised by Google

Dimensions: Howse: 198x309 mm. Pepys: 193x298 mm. Note the irregular shape of the plate mark (bottom left).

This plate is the only one to have been included in Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis Britannica. An examination of the volumes held by different libraries and digitised by Google shows that there was no consistency as to which volume, or where exactly in the volumes the etching was inserted. It has been observed bound into both volumes one and three.

Reproduced in:

- Frances Willmoth, Sir Jonas Moore (1993), p188. Plate 10a only

- Allan Chapman, The Preface to John Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis Britannica (1982), Fig.14, p.115

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975), p.56 & 57. Plates 10a and 10b printed separately)

- Derek Howse, Greenwich Observatory (1975), Fig.68.

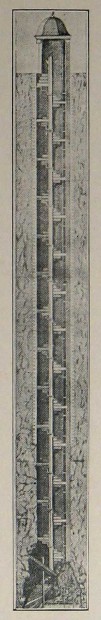

(A) Petus 100 pedum ... , Well of 100 feet. (B) Partes Instrumentorium, Parts of instruments (Howse Plate 12)

The titles of the two images on this plate are: (A) Puteus 100 Pedum Ad Parallaxes Terrae Observandus Pr Paratus, (B) Partes Instrumentorum Pertinentium Ad Speculam Astronomicum. This translates as: (A) Well of 100 feet equipped for observing the parallaxes of the Earth, (B) Parts of the instruments pertaining to the astronomical observatory.

Dimensions: Howse: 645x159 mm. Pepys: (A)72x632 mm (including title), (B)74x632mm (including title).

Only two copies of the etching are known. The first, which remains as printed, is held in the Observatory Archives at Cambridge (RGO116/1/10). The second is in the Pepys Library and is in an altered state, the two halves having been separated and then mounted by Pepys in the reverse order.

For copyright reasons, only a low resolution copy of the left side of the etching can be reproduced here. Published in Webster’s, Greenwich Park its History and Associations (1902), it was reproduced without the title (which was engraved at the bottom) and was made from the copy held at the Observatory (since catalogued as RGO116/1/10).

RGO116/10 copy reproduced in:

- Allan Chapman, The Preface to John Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis Britannica (1982), Figs.11, 16 & 17, p.112 & 117. Showing some, but not all of Plate 12b only (the Parts of Instruments), but including the Towneley Micrometer

- Derek Howse, Francis Place (1975), p.60 & 61

- Derek Howse, Greenwich Observatory (1975), Fig.52 (Plate 12a – which for the purposes of reproduction has been divided into two halves horizontally, which have then been printed side by side), Fig.53 (part of Plate 12a – detailed view of eye end of Well Telescope), Fig.101 (part of Plate 12b – The Towneley Micrometer)

- A.D. Webster, Greenwich Park its History and Associations (1902). Well telescope (Plate 12a) only.

Pepys copy reproduced in:

- Frances Willmoth, Sir Jonas Moore (1993), p191.

Proof before letter copies

Proof before letter copies are rare and only impressions made from Plates 4 (one copy) and 9 (two copies) are known.

Plate 4 before the inscription was added. Digitised by the British Library and released under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark (No Known Copyright). King George III collection, British Library shelfmark: Maps K.Top.17.1-3.a.1

Link to image as released on Flickr

The National Maritime Museum has a proof before letter impression from Plate 9 (Object ID ZBA1808) – Prospectus Intra Cameram Stellatam (the Octagon Room), which was transferred to the Museum on the closure of the Royal Greenwich Observatory in 1998. According to the 1926 Inventory (RGO39/5/271) it was acquired in June 1924 along with various other pictures including Plates 8, 10 and 11. It can be viewed on the Museum’s website via the link below:

Prospectus Intra Cameram Stellatam (digitised image) on the National Maritime Museum website

The Society of Antiquaries also owns a proof before letter impression of Plate 9. Stamped on the front with the Society’s mark, it is reproduced in the National Maritime Museum guide book (now obsolete) titled The Old Royal Observatory, The Story of Astronomy & Time (c.1990), ISBN 0-948065-05-02 (NMM Neg. No. 8972).

Typographical and other errors on the plates

The following errors have been identified. Whose fault they were is a matter of speculation.

- Plate 2 (Map of Greenwich Park): the text reads ‘Scale of Feet’ when it should have said ‘Scale of Yards’.

- Plate 3 (Plan): the Well Telescope is shown in the wrong location. The Octagon Room is rotated through 90 degrees in an anticlockwise direction relative to the ground floor. The figure of 34 feet given for the Octagon Room’s length and width appear to be incorrect unless they also include the thickness of the walls.

- Plates 3 & 12a (Plan and Well Telescope): the well is described as being 120 feet deep on Plate 3, but 100 feet deep on Plate 12a.

- Plate 11b (Equatrial Sextant): the inscription states ‘Fanis’ rather than ‘Facies’.

Measurements made on the object glass of the Well Telescope in 1955 indicated that its focal length was about 87 feet. (87 feet 5 inches ±0.7 inches in sodium light, 86 feet 11.2 inches at λ5270 and 87 feet 7.7 inches at λ6220). See The Observatory, Vol. 76, pp. 25–26 (1956) for more details. Additionally, measurements made with a barometer on 20 February 1679 led Laurie (1956) to infer a depth of 130 feet.

Plates held in different collections

The six organisations and archives mentioned above that are known to hold significant numbers of the etchings are:

Pepys Library, Magdalene College Cambridge (twelve plates)

Royal Society of London (nine plates)

Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives (nine plates in RGO116/1 and RGO116/2)

Greenwich Heritage Centre (ten plates)

British Museum (eight plates)

Society of Antiquaries of London (nine plates)

The table below shows the number of copies held in each collection and includes duplicate copies and additional copies with a different provenance which are both shown as (+1):

Plate |

Pepys |

RGO116/1 |

GHC |

Royal Soc. |

BM |

Soc. Antiq. |

RGO116/2 |

|

| 1 | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | |

| 2 | 1 | — | (+1) | — | — | — | — | |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1(+1) | — | — | |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1(+1) | 1 | 1 | |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

1 | |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

1 | |

| 8 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

— | |

| 11 | 1 | 1(+1) | 1 | 1 | — | 1 |

— | |

| 12 | 1 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Total | 12 | 9 |

9 (+1) |

9 | 8 | 8 | 5 |

The Pepys Library

Samuel Pepys. Attributed to John Riley. Oil on canvas, circa 1690. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license (see below)

Prior to mounting, each page of the album was marked out with a boarder of red tramlines drawn along the four edges and crossing over each other near the corners. Within the tramlines two guide lines were marked feintly in pencil, one running horizontally dividing the page into two equal sections, the other running vertically and dividing the space into two unequal sections with the side nearer the fore-edge being about one inch narrower than the other. Each page was also numbered in ‘black’ ink at top centre beneath the tramlines. Between them, the twelve etchings are mounted in four double-page spreads. Eight of the etchings are mounted two to a page, one above the other. The remaining four all straddle a double page. Each etching has been trimmed to the boarder or edge of the print, pasted in using the guides, and then had a thick black line drawn around it to frame it. Plate 12 has been cut into two halves, each of which is mounted separately. Each of pages 261-269 is headed ‘Thames & its views’, the heading being written on the side of the page closest to the fore-edge and level with the page number. The arrangement of the pages, which was driven more by the aesthetics than subject groups, is as follows:

Page no. |

Plates/comment |

|

| 261 | Blank apart from the words ‘Views of the Observatory in Greenwich Park’, which occupies three lines in the centre of the page. | |

| 262 | Top: Plate 8 (Prospectus Australis). Bottom: Plate 5 (Prospectus Septentrionalis) | |

| 263 | Top: Plate 7 (Prospectus Orientalis). Bottom: Plate 6 (Facies Speculae Septen) | |

| 264 & 265 | Top: Plate 4 (Prospectus versus Londinium) Middle: Plate 12a (Well telescope), on its side, top to the left Bottom: Plate 12b (Parts of instruments), on its side, top to the left |

|

| 266 | Top: Plate 10 (Summerhouse & Quadrant). Bottom: Plate 11(Sextant) | |

| 267 | Top: Plate 9 (Octagon Room). Bottom: Plate 3 (Plan) | |

| 267 & 269 | Bottom: Hollar’s Long view (state ii) (a cross between Place Plates 5 & 6, but originally made in 1637 while Greenwich Castle occupied the site on which the Observatory was built). Its extreme length means that it is folded in at either end. Above this and occupying a good ⅔ of the page is Plate 2 (the map of Greenwich Park) which has been folded in at the top and had Plate 1 (the Title Plate) pasted on to its back with a now disused second fold in the opposite direction to the first immediately above it. Two horizontal tears are present where the two horizontal folds are crossed by the vertical fold where the map straddles the two pages. All the folded sections have been reinforced at some point |

|

| 270 | Blank | |

When Pepys obtained the prints is not known, but Pepys knew Moore, who in 1676, was appointed a Governor of the Royal Mathematical School with which Pepys was closely associated. Flamsteed too was associated with the school, giving instruction to the boys and later becoming a Governor in 1681.

As Secretary to the Navy and a Fellow of the Royal Society, Pepys was well connected with many of the other key players of the time of the Observatory’s founding. Having been elected to Council in 1672, 1674 and 1676, after a break in service he was relected in 1681, becoming President in 1684. Lord Brouncker who was both President of the Society from its founding in 1662 until 1677 was not only a colleague on the Navy Board but also a guest at the Observatory with Moore on 1 June 1676, when a partial solar eclipse took place and the King was expected to attend (though in the event, he didn’t). Given that Pepys was an avid collector of prints, it would seem likely that he acquired his set of etchings either before his term of office as President ended in 1686, or perhaps in 1697 when he corresponded and met with Flamsteed on several occasions, recording that on 21 September he was given ‘Some account of the Erection of the The Observatory at Greenwich’ – the copy of which survives in the Pepys Library (Flamsteed Correspondence Vol.2),

Plates 6, 9, 10b, 11a and 12 from the Pepys Library were reproduced by Frances Willmoth in her book Sir Jonas Moore (1993) and Plate 9 in her book Flamsteed’s Stars (1997). Plates 2 and 7 were reproduced by John Bold in his book Greenwich (2000).

The Royal Society

The Royal Society’s collection contains nine of the twelve etchings. They are bound together under the title Ichnographia Speculae Regiae Grenovici exquisite facta curante Jona MOORE, in a larger volume of tracts (Catalogue Reference: Tracts X32/4). The title is taken from the words etched on Plate 2, the first part coming from the Plate’s title and the second (curante Jona MOORE) from the penultimate line of the inscription on the tablet included on the plate.

The collection appears under the same title and author in the 1839 catalogue (Click here to view). The earlier provenance is under investigation. It is not clear if the collection is catalogued under Moore’s name because he donated them, because he commissioned them of simply because his name appears on Plate 2.

All the etchings are folded and have been attached to the volume via a strip pasted immediately to the right of the fold. As a result, it is not possible to open them flat. Plates 3 and 4, which are larger, each have an additional fold. All have good margins beyond the plate mark except Plate 3 (Plan of the Observatory), which has been trimmed on the left and right edges into the print. This has resulted in the loss of the line surrounding the plan (but not the plan itself).

The cataloguer has counted each of the two images on Plates 10 and 11 as separate plates and recorded the number of plates as eleven rather than nine.

Low resolution watermarked copies can be viewed at the Royal Society Picture Library.

The British Museum

The British Museum has two sets of etchings, each of which has a different provenance. The most important set consists of eight etchings bought from Edward Daniell in 1865, who had acquired them at auction earlier that same year (sale Sotheby’s, 10-11.v.1865/126). They had previously been owned by John Towneley (1731–1813), who appears to be a direct heir of Richard Towneley, a friend and correspondent of Flamsteed and the man who designed the so-called Towneley micrometer mentioned above.

In 1676, while the Observatory was still under construction Flamsteed sent Richard Towneley a letter, dated 22 January in which he had drawn a sketch plan (with accompanying key) of the Observatory (RS MS/243/19). Given that in 1680 Flamsteed informed Towneley that he had sent sets to his (Towneley’s) brother in Paris for Roemer and Cassini, it seems highly likely that Towneley himself was also an early recipient of a set. Given the rarity of the prints, it would seem likely that the British Museum set consists of some or all of those given by Flamsteed to Towneley.

In addition to the Towneley set, the British Museum holds two further copies of the etchings (Plates 4 & 5). These were bought from John Gregory Crace in 1880. Previously owned by Frederick Crace, their earlier provenance is unknown. They can be viewed via the links below:

Plate 4, Museum Number: 1880,1113.5511

Plate 5, Museum Number: 1880,1113.5512

Click here to read more about the Towneley family.

The Royal Observatory Archives

The Royal Observatory owned at least three sets of etchings. Two of these are now preserved in the archives at Cambridge. Their class-marks are RGO116/1 and RGO116/2 respectively.

Francis Baily, c.1829. Engraving by Thomas Lupton after Thomas Phillips. Cropped and reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license courtesy of the University of Cambridge, Institute of Astronomy Library

‘Several valuable presents have been received, among which I may specify two made by one of the members of the Board of Visitors, Mr. Baily. These are, the edition of Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis, published by Halley [The 1712 edition], and a set of engraved views of the Observatory apparently made by Flamsteed. As works of general astronomical literature these are extremely valuable, but more particularly so when considered in reference to the archaeology of the Observatory. With a view of handing down from the present time what may in future be considered as valuable representations of the Observatory, I have been desirous of contributing drawings of its present state: and I have the pleasure of calling the attention of the Board to two drawings made by a person in my family. These I propose to add to the same collection; and a series of interesting pictures will in time, I hope, be gradually formed.’

A note dated 5 March 1838 in Baily’s hand (RGO116/1/11) that accompanied the plates records that

‘The accompanying plates (nine in number) were found by me in an imperfect copy of Dr Halley’s edition (1712) of Flamsteed’s observations...’

A stray copy of Plate 11 (the Equatorial Sextant) has managed to find its way into the set and it is no longer known which of the two copies RGO116/1/8 or RGO116/9 is the one that was part of the original 1838 set. All the etchings in RGO116/1 are in card mounts ready for display. Although the plate margins are visible, it is now impossible to tell how much the margins around the plate mark might have been trimmed without dismounting them.

So keen was Airy to extend his collection of images of the Observatory, that on Wednesday 17 November 1847 he ‘went to the Library of the Society of Antiquaries to see some prints relating to Greenwich’ (RGO6/2/24) and appears to have arranged for three of them to be copied for him, including one by Francis Place that was not included amongst those given to him by Baily (Plate 8, Prospectus Australis). For reasons unknown, a copy of Plate 5 was made, even though he already had an original copy of it. These two drawings together with the copy of the other print are preserved in RGO116. They all carry the additional words ‘Copied in the Library of the Society of Antiquaries 1848’. The copy of Plate 5 is catalogued as RGO116/2/6 and Plate 7 as RGO116/2/7.

Of the five original Francis Place etchings in RGO116/2, four have been trimmed to the edge of and into the print. The fifth (Plate 3) has good margins. Their date of acquisition is currently uncertain, but is presumably post 1838. What is also clear, is that they have come from a number of different sources and were not all printed at the same time (more on this below).

According to the 1926 inventory (RGO39/5/271), copies of Plates 8, 9, 10 and 11 were acquired (from an unspecified source) in June 1924 and at the time of the inventory were in the Astronomer Royal’s Room, which is where the 1933 inventory (RGO39/6/257–60) also places them. Plate 9 was the proof before letter copy of the Octagon Room that was transferred to the National Maritime Museum in its frame in 1998 when the Royal Greenwich Observatory was closed. The 1926 and 1933 inventories do not state if the etchings were framed or unframed, but given the nature of the list and the absence of the Baily set in the inventory (they were regarded as part of the Library and Manuscript Collection), it seems likely that they were hanging on the wall. It is possible, but by no means certain that Plates 9 and 10 are the ones that are now in RGO116/2. The whereabouts of Plate 8 is most definitely unknown. This is a great pity, as the RGO archive does not knowingly hold an original copy.

Greenwich Heritiage Centre

The nine etchings held by the Greenwich Heritage Centre are all bound into what appears to be one of the ‘imperfect’ copies of the 1712 Historia prepared by Flamsteed for his friends ‘as Evidences of the malice of Godless persons’.

All the plates have good margins. Plate 4, which is oversize for the volume, has been folded in with the margins cut back slightly on the top right-hand end to allow this to happen. One image (Plate 9?) was detached by cutting (in the 1970s for display?), but has since been re-attached.

In addition to the Historia, the Centre also holds separately, a copy of Plate 2 (the map of Greenwich Park), which as noted above has had the scale corrected (by hand) from Scale of ‘Feet’ to Scale of ‘Yards’.

Four of the nine etchings (all cropped and some digitally altered) were reproduced in Clive Aslet’s The Story of Greenwich (1999): Plates 4, 6, 7 and 9,

Further details of this volume of the Historia are given below.

Sociey of Antiquaries of London

The Society of Antiquaries holds copies of eight of the etchings. When they were acquired is not known, but some or probably all of them were in the collection by 1847, as that year, they were viewed by Airy, who arranged for two of them to be copied (Plates 5 & 7). These two copies are preserved in RGO116 and carry the additional words ‘Copied in the Library of the Society of Antiquaries 1848’. All eight etchings have visible plate marks, and all have been trimmed to close to the plate margin. All have the society’s rectangular ownersip stamp in the bottom right hand corner (in most cases outside the plate mark). Six (not Plates 3 or 6) also carry the society’s larger circular stamp which is entirely within the print boundary on Plates 5, 7, 8 & 11. Plate 9 is a proof before letter copy. This fact, taken together with the inconsistency in the way the prints have been stamped, would seem to indicate that the Society (and or the donor) did not acquire them all at the same time.

In about 1830, the society began to organise its prints, drawings and paintings into albums. The eight Francis Place etchings together with an unrelated print of the Observatory were mounted on leaves/pages 21–24 of the Kent Red Book (part 2). As with the other items in the album, they were only mounted on one side of each leaf (recto, blank verso). The album also contains other prints marked ‘Soc:Ant:Lond The Gift of Dr. W. Bromet’, referring to a bequest made in 1850/51. These appear both before and after leaves 21–24. On the asumption that the album was not compiled on loose leaves that were later bound, this would suggest that the Place images were probably mounted in the 1850s and that the Soceity owned all eight of them by that date. The dimensions of the album are approximately 20 inches wide x 25 inches high.

In 1974, the four leaves carrying the Francis Place prints were cut from the album and loaned to the National Maritime Museum (where Derek Howse worked). The back of leaf/page 20 carries the following inscription in pencil:

‘Pages 21–24

8 F. Pace Engravings & Prospect of Greenwich to Maritime Museum on Feb 30 [19]74’

The error in the date is rather curious and could have arisen if a mechanical watch showing the date was being used and the user had forgotten to advance the hands at the end of February – having said that, 2 March was a Saturday, not a weekday.

After the pages had been removed, either the Society or the Musuem cut out the individual prints by cutting back the page on which they were mounted very close to the sides and bottom of each print. Margins of different sizes were left along the top edge varying from virtually nothing up to a maximum of 30mm. Each etching remains attached to the paper from the album page.

An analysis of the Society’s card index together with an examination of the feint mirror like impressions on the back of the paper on which the prints were mounted, shows that in the Kent Red Book the prints were mounted two to a page (with the addition of an unrelated print on p.21) in the following order:

Page |

top |

bottom |

centre |

|

| 21 | 5 | 6 | unrelated print of the Observatory |

|

| 22 | 10 | 11 | — | |

| 23 | 7 | 8 | — | |

| 24 | 3 | 9 | — |

The prints were mounted separately for display in the Musuem’s 1975 exhibition commemorating the tercentenary of the Observatory which was held in the in the Queen’s House. They are listed and credited in the Guide to the exhibition section that formed the second part of Greenwich Observatory 300 years of Astronomy, Ed. Colin A. Ronan (1975).

The Museum also photographed some (probably all) of the etchings. At least two of these were subsequently published: Plate 8 in Howse’s book about the etchings and Plate 9 in the National Maritime Museum guide book (now obsolete) titled The Old Royal Observatory, The Story of Astronomy & Time (c.1990), ISBN 0-948065-05-02 (NMM Neg. No. 8972).

The nine prints were returned to the Society bound into a soft cover album constructed by the Museum, each print having been attached by a paper strip (rather too carelessly in some cases) to the front of the original paper backing and sometimes to the edge of the front of the print as well. The attachment was to the top edge with the exception of Plate 3 (the plan of the observatory) where it was attached to the bottom and the unrelated print where it was attached to the left-hand edge. In some cases, the paper strip overlaps the edge of four of the etchings (Plates 3, 6 (right end only) 10 & 11). The mounting of Plate 3 is particularly shocking as the strip has not only been stuck onto the printed part of the etching, it has been pasted over the top of the Society’s rectangular ownersip stamp. An attempt has been made to reveal the obscured section by tearing back the edge of the new paper strip. Part of the distance scale remains obscured and there is a small glue stain near the bottom edge. Two other etchings also have minor glue stains which were introduced at this time (Plates 10 & 11). After alternating the prints with blank leaves they were bound into a blue cover by punching them through the outer edge of the attachments and sewing them together.

The order in which the plates are mounted is: 5, 6, 10, 11, 7, 8, 3, 9, unrelated print. In other words, with the exception of the unrelated print, they are in the same order as before. After their return, the folllowing inscription in ink was written on the front cover:

‘Plates by Francis Place. in the Society’s Possession

lent to Greenwich & returned mounted.

They are extremely rare.

See. Howse. Derek. “Francis Place and the early History

of [the] Greenwich Observatory.”

He used most from Pepy’s annotated “London & Westminster” [not true]

Plt8. Prospect Australis was ours.’

The different states due to damage and attempted repairs of the printing plates

Plate 6 (detail). © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). The vertical scratch (top right) and the two white spots (top left and centre) are present on all the copies studied. So too is the spattering of marks present across much of the this part of the print. As no copy has been discovered without this damage, there is a real possibility that it occurred before any prints had been struck off

An examination of the extant copies of the etchings together with the known contemporary references seems to suggest that prints were struck from the plates on at least three and perhaps four separate occasions.

- Before 1680 as evidenced by Flamsteed’s letter of 14 January 1679/80 to Towneley (see above)

- 1682 as evidenced by Flamsteed’s letter to Hevelius of 19 September 1682 (see above)

- Around 1716 or perhaps as late as the early 1720s as evidenced by a comparison of the prints bound into the ‘imperfect’ 1712 Historia and those in other sets (see below for details). The early 1720s seems the most likely date for the copies from Plate 11 to have been printed for inclusion in the 1725 Historia

The following sets of etchings are all of reasonably well known provenance. Each has the appearance of having been put together from a single source at one specific point in time and not added to since.

- The eight plates in the British Museum Towneley set (BMT)

- The nine plates at the Royal Society (RS)

- The twelve plates in the Pepys Library (Pepys)

- The nine plates in the RGO archive extracted from the ‘imperfect’ 1712 Historia (RGO116/1)

- The nine plates bound into the ‘imperfect’ 1712 Historia at the Greenwich Heritage Centre (GHC)

The first three sets of images (BMT, RS and Pepys) are likely to have been struck off by 1682 or soon after. The second two sets (RGO116/1 and GHC) were not assembled until 1716 at the earliest as they are or were both bound into the much altered editions of the 1712 Historia assembled by Flamsteed for his close friends following his removal of the pages which he wished to reuse in a revised edition.

The five sets of etchings have six plates in common. Of these, just one (Plate 9) has a similar appearance in all five sets. The remaining five (Plates 4, 5, 6, 7 & 10) appear to exist in two different states as a result of damage and attempted repairs to the printing plates which is considerable in the case of Plates 4, 5 & 6 and minor in the case of Plates 7 & 10. An impression of Plate 5 also exists in an earlier state still in the British Museum Crace set (BMC).

An examination of the different copies of Plates 4, 5, 6, 7 & 10 shows that those in the British Museum Towneley, Royal Society set and Pepys set are similar to each other and representative of the earlier state. Likewise those in the Observatory archives (RGO116/1) and Greenwich Heritage Centre are similar to each other and representative of the later state.

*****

In the following sets, the images are arranged in the order in which they are thought to have been printed, with the earliest state at the top.

Plate 4

The splattering of marks above the river to the immediate left of the boundary wall of the Observatory (on either side of the fold) is present in the GHC and RGO sets, but not in the BM, RS and Pepys sets. The etching was too large to be bound into the Historia without folding, which is why there is a fold mark on the second copy.

Plate 5

In the top image (BMC), apart from the foxing, there is a splodge about halfway between the top of the telescope and the top of the telescope mast. There is also a fairly feint near vertical scratch on the plate that starts near the right-hand side of the roof of Flamsteed House and ends more-or-less at the bottom of the telescope. In the second image (BMT) there is also a highly visible horizontal scratch that runs across the centre of the image. The scratches and the splodge are present in both the BMT, RS and Pepys sets. In the bottom image (GHC), an attempt has been made to rectify the damage by polishing out both scratches and the splodge. In the process, the hatching on some of the clouds has been reduced in intensity as has the definition of the lower right hand edge of Flamsteed House and more importantly the top end of the mast telescope. The RGO116/1 image is similar.

Plate 6

Two things are particularly noticeable. In the lower image (GHC), part of the left hand row of trees has been entirely scrubbed out. The definition of the Giants Steps is also much reduced as is the definition of some of the clouds. As no copy has been found that captures the etching between the two states shown here, one can only speculate as to nature of the damage that necessitated such a drastic and damaging clean up of the printing plate.

Plate 7

In the lower image, there is a vertical splattering of marks which extends horizontally towards the left at its lower end. It is located just below and to the right of the group of birds in the centre. It is present in the GHC and RGO116/1 copies, but not in the BMT, RS and Pepys copies.

Plate 9

There are no discernable differences between the different copies printed from Plate 9.

Plate 10

Differences between the BMT/RS/Pepys copies and the GHC/RGO116/1 copies are present, but minimal. The key difference is the line running across the length of the bottom step and two small marks, one of which is on the bottom step just above the letter d. The second is to its left on the step above.

*****

An analysis of Plates 5, 6 and 7 in RGO116/2 indicates that Plates 6 and 7 are similar to those held by the Royal Society and British Museum and that Plate 5 is similar to that in RGO116/1 and at the Greenwich Heritage Centre.

The decision to omit most of the plates from the 1725 Historia

Plate 11 (the sextant) was the only etching to have been included in the 1725 Historia. This section explores possible reasons why the other plates were not included.

We know from Crossthwait’s letter to Sharp (21 April 1721), that it was proposed to make alterations to Plate 2 (the map of the Park) and print more copies from it. Since there are only two known copies, both of which have the incorrect scale printed on them, it seems that the alterations were not in fact made and perhaps no further copies were printed after about 1680.

Crossthwait’s letter could be taken to imply that at this point in time, Margaret Flamsteed may have been planning to include several or all the Place etchings in the 1725 Historia. Cost issues around the engraving of plates for Flamsteed’s Atlas Coelestis, which was eventually published in 1729, but which was also being prepared at the same time, may have caused her to have had second thoughts about the Place etchings. Assuming that 300 copies of the 1725 Historia were to be produced, printing all the Place Plates would have required well in excess of 3,000 extra leaves to be printed which would have involved considerable extra cost.

Another and perhaps more important consideration was the state of the printing plates themselves. As was observed above, all the plates showing the external views had become damaged leading to a significant degradation of the image. Whilst the plates showing the internal views and views of the instruments, were seemingly in good condition, two of the instruments they portrayed (the Mural Quadrant and the Well Telescope) had been a failure from the start. Publishing inferior quality etchings of the buildings along with etchings of the useless instruments was hardly likely to be conducive to projecting Greenwich as a world class Observatory with a world class astronomer as its head!

That the etching of the sextant was included is perhaps not surprising as Flamsteed included a detailed description of it in his preface to the Historia. It was his main observing instrument until 1689 when it was superseded by his Mural Arc and was the only instrument apart from the Mural Arc for which he wrote a description. Only one other plate might perhaps have been sensibly included. This was the view of the Camera Stellata (the Octagon Room), which contained the clocks with which Flamsteed was able to establish that the Earth was isochronous (spinning on its axis at a steady rate) as well as the so called ‘equation of time’. It also housed the telescopes Flamsteed used to observe eclipses of Jupiter and the Moon.

Things that Howse omitted to mention in his book about the Francis Place etchings

In his otherwise excellent book, Francis Place and the early history of the Greenwich Observatory, there are several important things that Howse failed to mention:

- That some of the images had been cropped (and by differing amounts)

- The existence of proof before letter copies

- The extent to which any of the photographic images were cleaned up in a pre digital age (if at all) to remove some of the blemishes. Plate 4 looks suspiciously clean.

- That the National Maritime Museum, which was credited with many of the images, did not in fact own any of the Francis Place etchings at the time that the book was published in 1975. The National Maritime Museum Picture Library holds negatives of photographs taken of the Place etchings held in several different collections. These would have been taken at Howse’s request. The table below has been compiled by comparing the defects (marks, scratches etc.) on the images published by Howse with the originals in different collections

- That the underlying quality of the etchings varied hugely from one collection to another. Not only has this created the impression that all the existant copies are similar, it has also helped obscure one of the main reasons why most of the etchings were excluded from the 1725 Historia

No. |

Title |

Image source (*=acknowledged by Howse) |

|

| 1 | Vivarium Grenovicianum ... |

British Museum* | |

| 2 | [Map of Greenwich Park] |

Pepys Library* |

|

| 3 | Ichnographia Speculae Regiae ... |

RGO116/1/1 | |

| 4 | Prospectus versus Londinium | Original source unidentified. NMM neg no. A395 | |

| 5 | Prospectus Septentrionalis |

RGO116/2/2 | |

| 6 | Facies Speculae Septen |

RGO116/2/3 | |

| 7 | Prospectus Orientalis |

RGO116/2/4 | |

| 8 | Prospectus Australis |

Society of Antiquaries* | |

| 9 | Prospectus intra Cameram Stellatam |

Original source unidentified. Possibly Greenwich Heritage Centre. NMM neg no. 8972 | |

| 10a&b | Domus Obscurata ...& Quadrans Muralis Merid: ... | RGO116/1/7 | |

| 11a&b | Facies Sextantis Anterior ... & Fanis Sextantis Posterior ... | Probabally RGO116/1/8 or RGO116/1/9 | |

| 12a&b | Petus 100 pedum ... & Partes Instrumentorium | RGO116/1/10 | |

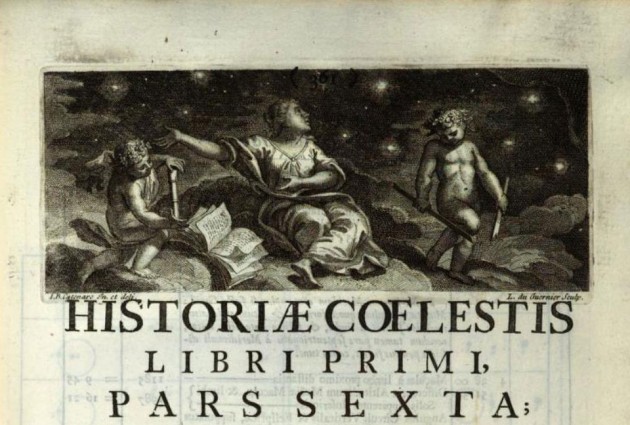

The images and plates included in the 1712 Historia

The 1712 Historia contains the following illustrations: frontispiece, dedication plate, five headpieces (each of which was used twice in sequence) and four pages of diagrams. The diagrams were engraved by I. Senex (John Senex) from drawings that were presumably made by Flamsteed or one of his assistants. The artists of the other illustrations were Juan Batista Catenaro (also known as Giovanni Battista Catenaro) who drew five, Jacobus Gibs (James Gibb(s)) who drew one and Louis Du Guernier who also drew just one. The engravers were Du Guernier (six illustrations) and George Vertue (one). Unlike the Place etchings, the name of the artist and engraver was included on every plate except those containing the diagrams, where the artist’s name was omitted). The evidence suggests that the headpieces were not contemporaneusly printed with the pages, but were added later.

Plate |

Artist |

Engraver |

|

| Frontispiece | Catenaro | Vertue | |

| Dedication plate | Gibs | Du Guernier | |

| Headpiece 1 | Catenaro | Du Guernier | |

| Headpiece 2 (sextant) |

Du Guernier | Du Guernier | |

| Headpiece 3 |

Catenaro | Du Guernier | |

| Headpiece 4* | Catenaro* | Du Guernier* | |

| Headpiece 5 | Catenaro | Du Guernier | |

| Figs.77–94 exc.85** | Flamsteed? | Senex | |

| Figs.95–112 | Flamsteed? | Senex | |

| Figs.113–136 | Flamsteed? | Senex | |

| Figs. Comitum jovialium (eclipses of Jupiter) |

Flamsteed? | Senex | |

| * The names of Catenaro and Du Guernier omitted from the headpiece on p.193 in order to reduce the overall height of the engraving. |

|||

| ** The figures with numbers lower than 77 were omitted from the 1712 Historia, but included in the 1725 edition. | |||

Of the five headpieces, the Sextant stands out as the only one not to be full of astronomical iconography and symbolism. How much Flamsteed approved or disapproved of it has to be a matter of some debate. Had he allowed copies of the Place etching to be printed, the Sextant headpiece may not have been commissioned. Although one suspects Flamsteed was less than happy with Du Guernier’s rendering, the economics of having the two sheets on which it had been used reset and reprinted for the 1725 Historia may well have been the reason that he put his objections (if any) to one side and retained the pages for reuse.

Not much is known about how Catenaro, Du Guernier, Senex, Gibs and Virtue came to be involved. The little information we have, comes largely from two letters. The first was sent to Newton by Arbuthnot, probably in early 1712:

‘Frontispiece } li s d

Monument } 102.2.2

3 Headpieces }

I have agreed with the Graver that did the head pieces for 20 lb for Graving the inscription with the Ornaments [dedication plate]. he sayes 29 lb but I beleive he will not insist on more than 20. So that ther will be in all 51 lb due to Du Guernier & 30 lb to the other Graver George Vertue, there must be a present to Catinar, the painter, who has really been at a great deal of trouble if it were my own business I could not offer him less than 20 lb. Dr Hally expects as much as is sav’d viz 125 lb that should have been given to Mr Flamsted 1 think ifhe had 25 lb more it will not be Grudg’d by Mr lord Treasurer so that will make in all [150 lb.] the Account will stand thus

for printing &c ― 102

To Dr Hally ― 150

To the tuo Gravers ― 80

To Catinar ― 20

These are all the requisites for the acct The sooner it is given in the better. (I forgott indeed some tuo Guineas or so for drawing the Architecture to Mr Gibbs. I refer all to your own judgement being with the greatest respect’ (The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, Vol. 7)

The second letter, dated 14 February 1711/12, was sent by Newton to Robert Hartley (Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer), the Lord High Treasurer when settling the accounts. There is no mention of a payment to Gibbs:

‘… there is due to Mr. Churchill the Bookseller for paper & printing 98£. 11s. as in his Annexed Bill & to the Graver du Guernier 51£. 10 for Graving the Mausoleum [dedication plate] and Four other plates as in his annexed Bill, & to the Graver Vertue 30£ for Graving the Frontispiece, and there is a plate still to be Graved which will cost 7£. 10s And the rolling off and some other Graving Work Contracted for by Dr. Halley comes to 7£. 4s as in his annexed Bill, … , And Mr Catinaro the painter may deserve 20£. For designing what was to be Graved.’ (The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, Vol. 5)

The inspiration for the designs of the headpieces (apart from the one with the sextant) remains unclear, suggesting that they may have been original to Catenaro rather than adapted from elsewhere. On the other hand, two of his designs (headpieces 4 and 3) were later incorporated by George Bickham into the top and bottom of his engraving The apotheosis of Newton which was first published in 1732.

The Louis Du Guernier image of the Sextant

The Sextant as redrawn and engraved by Louis Du Guernier. It was commissioned as a headpiece for the 1712 Historia. This particular copy was on one of the many pages extracted by Flamsteed for reuse in the 1725 Historia. Both images of the Sextant are from the copy of Volume 1 of the 1725 Historia in Lyon Public Library. Digitised by Google with later sharpening of the Du Guernier image

Copying other artists’ images was fairly commonplace in the early eighteenth century and Du Guernier seems to have followed the practice of accurately replicating the important elements whilst altering the less important ones. The following points are worthy of notice:

- The Equatorial Sextant is shown reversed on its mounting

- The Sextant has been copied with a reasonably degree of accuracy

- No attempt has been made to accurately replicate the interior of the Sextant House

- Du Guernier has concocted a new setting for the Sextant House and has included an alien building in place of Flamsteed House

- The Clock that Du Guernier has drawn is in a different case to that shown by Thacker

The clock is a troubling change, for it raises an important question. Is the difference due to artistic license on the part of Du Guernier, or did Flamsteed change the Sextant House clock for a different one after the Place etchings had been made? Although one suspects the former, but further research is required to definitively rule out the second.

The sections of the 1712 Historia

The 1712 Historia consists of two books (or volumes) bound as one. Book 1 contains the observations made from 1676–1689 and consists mainly of observations made with the Equatorial Sextant. Book 2 contains the observations made from 1689–1705 and consists mainly of observations made with the Mural Arc.

Following the preliminaries, the first volume is divided into seven numbered parts, each of which begins with a headpiece (HP) at the top of the page. The second volume is shorter, containing just three numbered parts and an eratis. Different copies have slight typographical changes on a small number of pages. Those that have been noticed are included in the comment column of the table below.