…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

People: James Hodgson

| Name | Hodgson, James (also known as Hodson or Hudson) | ||

| Place of work | Greenwich | ||

| Employment dates |

01 Apr 1695 – late 1702 |

||

| Posts | Servant & Assistant (to John Flamsteed) |

||

| Baptised | 1678, Feb 25? |

||

| Died | 1755, Jun 25 |

||

| |

|||

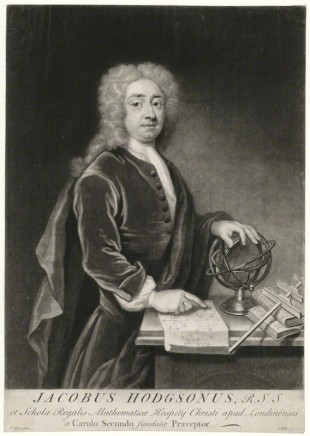

James Hodgson by George White, after Thomas Gibson. Mezzotint, circa 1720. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence (see below)

On 31 October 1702, Hodgson married Flamsteed’s niece, Ann Heming who since 1694 had been resident at the Observatory and in the care of Flamsteed and his wife. Although now married, she remained behind, at the Observatory until 1706 when she eventually moving out to join him. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1703 and in 1709, became Master of the Royal Mathematical School at Christ’s Hospital, a post he retained until his death.

Hodgson was an important aid to Flamsteed when the latter’s observations were published by the Royal Society without his approval (Historia Coelestis Libri Duo, 1712). After Flamsteed’s death at the end of 1719, Hodgson worked with his widow, Margaret, to have the ‘authorised’ version of Historia Coelestis published. This was published in 1725 and the Atlas Coelestis in 1729. On her death in 1730, Flamsteed’s papers and other relics from the Observatory were left to his son John Hodgson.

Flamsteed’s papers passed into obscurity until 1771, when they were found at Islington by the surgeon John Belchier. The Board of Longitude then purchased the papers from Mrs Elizabeth Tew, the widow of Hodgson’s executor, and returned them to the Observatory. They are now preserved in the Observatory Archive at Cambridge (RGO1). Of the relics: one of the two Tompion Clocks from the Great Room (Octagon Room) was given to the Royal Society in 1736 and the object-glass of the Well Telescope in 1737. Both Tompion Clocks survive, one in the care of the British Museum, the other in the care of the National Maritime Museum. That in the National Maritime Museum is believed to be the one given by Hodgson to the Royal Society. (Click here to read about the clock at the British Museum and a detailed provenance of the two clocks). The object-glass which is said to be 9.75 inches in diameter, 0.36 inches thick has been on loan to the Science Museum since 1932.

Further reading

Hodgson, James (bap. 1678?, d. 1755). Frances Willmoth, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

Hodgson, James (DNB00) (links to Wikisource)

'Greenwich near London': The Royal Observatory and its London networks in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Rebekah F. Higgitt.. British Journal for the History of Science (2019). ISSN 0007-0874 (doi:10.1017/S0007087419000244)

An account of the Revd. John Flamsteed, Francis Baily, (London, 1835)

The correspondence of John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal, ed. E. G. Forbes and others, 3 vols. (1995–2001)

Image licensing information

James Hodgson by George White, after Thomas Gibson. Mezzotint, circa 1720. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence. National Portrait Gallery Object ID: NPG D3042.

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan