…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

The demolition of Greenwich Castle

The Royal Observatory was built on the site of Greenwich Castle. Exactly when the Castle was demolished is unclear. The aim of this page it to take a look at sources that help shed light on the matter.

Introduction

Greenwich Castle in 1637. Detail from Wenceslaus Hollar's long view of Greenwich. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1856,0607.5 (see below)

Often known as Duke Humphrey’s Tower and sometimes as Millefleur, Greenwich Castle was erected in the 1430s by the brother of King Henry V, Duke Humphrey (1390–1447), who also built a manor house by the river at around the same time. This was demolished about 1500 and the much larger Greenwich Palace erected in its place.

Although the Castle appears in the distance in several seventeenth century views, there are no known images that show the Castle in any detail. Nor are there any known contemporary plans. One of the clearest images comes from Hollar's 1637 long view of Greenwich (above and below).

Wenceslaus Hollar's long view of Greenwich. Greenwich Castle is on the left. The Queen's house (completed 1635) with the Tudor Palace behind is in the centre. The etching was printed from two plates joined down the centre and first published in 1637. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1850,0223.254 (see below)

Remodeled in the 1520s, improved in the 1610s and most probably demolished at some point in the 1660s or early 1670s, the exact date of the Castle's demolition is unclear. What is certain, is that the Royal Observatory, whose construction began in 1675, was built on the site on which it had stood.

The journal of William Schellinks

Between 1661and1665 Jakob Thierry de Jong undertook a grand tour of Europe accompanied by the Dutch artist William (Willem) Schellinks (1627–1678) as his guide. Throughout their travels, Schellinks kept a journal. Those parts related to their visit to England were later translated into English and published in 1993.

On 14 August 1661, Schellinks recorded the following about his journey up the Thames:

'We came to famous Greenwich on our left, very pleasantly situated on the river. The royal palace stands close to the water along the river, a very large, long building first begun by . It was damaged during the recent troubles and is at present in a badly ruined state; it was used by Oliver Cromwell as a prison during the war against the Dutch, of whom many died there of privation and disease [The first Anglo-Dutch War took place from 1652-1654]. A little inland is the Queen's House or palace, a fine, stately building with many large and small rooms and nice stone spiral stairs with iron banisters [the famous Tulip Stairs] leading up to the upper rooms to the flat roof, which is lead-covered and railed in, from where one has beautiful views all around. This building too has suffered some damage in the recent war and is at present without furniture and pictures, but is now on the King's orders being repaired. There is a fairly large deerpark, surmounted by a wall, but the soldiers have killed all the game, which used to be here in large numbers. On a hill in this park are the ruins of a castle which has been raised to the ground by the parliamentarians’.

On a later visit to Greenwich on 25 October 1662 Schellinks recorded:

'At 10 o'clock in the morning we rode with Mr. Adrien Boddens, Mr. J. Seghvelt, and Mr. Samuel Hill to Greenwich, and looked at the King's House, now in somewhat better order than when we saw it anno 1661 on 7th September. On the hill in the park behind the house two avenues of trees had been planted from the bottom to the top, and near the top of the hill, where it was too steep to climb up, steps had been cut in the ground to walk up in comfort.

On the river side all the old buildings of the palace are pulled down to the ground, to make, to begin with' a large level area; His Majesty, who takes great pleasure in the place because of its beautiful situation by the river, and the understandingly pleasant view from the hill over the park, is planning to have a magnificent palace built there,'

Click here to read more about the Giant Steps which were constructed at some point between 1 September 1661 and 10 June 1662.

Pepy's diary

Pepys recorded the following in his diary on 11 April 1662:

‘At Woolwich, up and down to do the same business; and so back to Greenwich by water, and there while something is dressing for our dinner, Sir William [Penn] and I walked into the Park, where the King hath planted trees and made steps in the hill up to the Castle, which is very magnificent.’

Engraving from Walter Scott's Waverly Novels

Greenwich Park and Palace, Old London in the distance, Tower in Foreground built by Humphrey Duke of Gloster. Steel engraving by F W Topham from Scott's Waverley Novels, Abbotsford edition, vol. 7 (1845)

Beneath the engraving are the words 'From a Picture temp of tale', which is assumed to mean from a picture that was contemporary with the novel (which was historical). The original artist is unknown as is the picture's current whereabouts. Nor is it known if the picture was a genuine contemporary image or a later artist's impression. The buildings of the Palace and St Alphege's Church in the background suggest the former.

Click here to read the novel and view a list of the illustrations which includes both the artists and the engravers names.

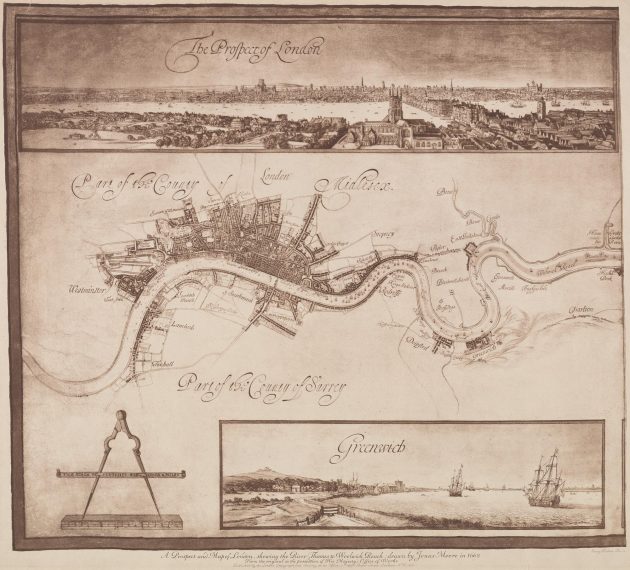

Jonas Moore's manuscript map of 1662

Appointed Surveyor General of the Ordnance on 28 July 1669, Jonas Moore not only became Flamsteed's patron, but was also influential in getting the Observatory built and in securing the post of Astronomer Royal for him. First appointed as Assistant Surveyor at the Ordnance in 1665, Moore's first commission from a government body came several years earlier in 1662. It was to produce a map of the Thames. He chose to entitle it as follows:

"A MAPP OR description of the River of Thames from Westminster to the Sea with the falls of all the Rivers into it the severall Creekes Soundings & Depths thereof and Docks made for the use of his Maties Navy, made by Jonas Moore Gent: by Warrant from Sr Charles Harbord Knt, his said Maties Surveyor General. In Pursuance of his Maties Warrant and Command under his Royal Signature Anno Domini 1662"

The royal warrant to which Moore referred is dated 7 February 1662.

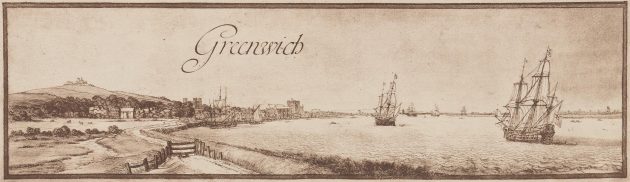

The plan (now preserved at The National Archives (Work38/331)) is large being more than six feet wide, two foot high and edged by a gold border with a black outline. Drawn on three pieces of joined velum, the map has become rather rubbed over time, possibly in part, because of people brushing past it when it was pinned to an office wall. As well as showing buildings, the map has a coat of arms (top centre), a cartouche containing the title above (bottom right) balanced by an image of a pair of dividers on a ruler (bottom left). There are also five good size watercolours? edged in gold. They are titled: The prospect of London (top left) and then in a row along the bottom from left to right: Greenwich, Wulwich (Woolwich), Erith and Graves End (Gravesend). They have been attributed by some to Wenceslaus Hollar, possibly on account of similarities between The prospect of London and known Hollar views. That said, no Hollar views remotely similar to the other four watercolours have been identified.

As far as is known, the complete map has never been reproduced. However, the western third was reproduced in monochrome by the London Topographical Society in 1912 (below) and the western half in full colour as the endpapers in Philippa Glanville's London in Maps (1972). A cropped version of The London Topographical Society publication was included by Peter Whitfield in his book London in maps (2006/2017). Interestingly, the original seems to have suffered further damage since the 1912 copy was made.

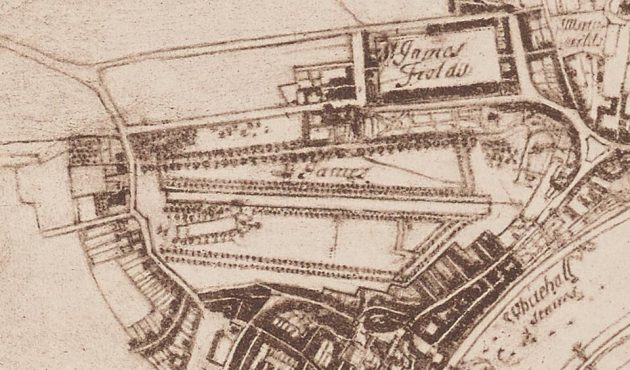

The section of Moore's 1662 Map published by the London Topographical Society in 1912. Reproduced courtesy of Yale University Library (see below)

The map includes not one, but two images of Greenwich Castle - one on the map itself and the other in the view of Greenwich. But how reliable are they as a guide to the state of the Castle in 1662? The three detailed map sections below help answer this question.

Detail showing St James's Park. In 1662 it was in the middle of being landscaped for Charles II by the French Garden designers André and Gabriel Mollet who added the canal (centre) that runs from east to west. The map shows the works in progress and is the only map known that captures the Park before 'the rounds' were added at the eastern end of the canal

As well as redeveloping St James's Park in the early 1660s, Charles II was also having Greenwich Palace rebuilt and Greenwich Park landscaped. None of these works are shown on the map. The Castle can be seen below the word Greenwich

The view of Greenwich shows the Castle standing on the hill. It also shows Greenwich Palace on the waterfront seemingly with all the buildings still standing. This suggests the view was copied from an existing (and now lost?) image that predated the map's production

Taken together, it would seem that whilst some parts of the map were completely up to date, others were rather dated. As such, the Castle's appearance cannot be relied upon as representing its true state in 1662.

John Webb's proposed 'Grot and Ascent'

In around 1665, John Webb, who was responsible for rebuilding the Palace proposed the construction of a 'Grot and Ascent' to close the view at the top of the Giant Steps. Although it was never constructed, it would have required the Castle to be removed so as not to distract from the scene. For more on the Grot and Ascent see John Bold's Greenwich (2000).

John Evelyn's diary

On 1st June, 1667 Evelyn wrote in his diary:

'I went to Greenwich, where his Majesty was trying divers grenadoes shot out of cannon at the Castlehill, from the house in the park; they broke not till they hit the mark, the forged ones broke not at all, but the cast ones very well. The inventor was a German there present'.

Exactly what was being fired at is unclear; but what is clear, is that by 1667, both the Giant Steps and the avenues that we see in the Park today had been created. If damage to these was to be avoided, the shots would have had to be fired over the top of the trees on the terraces that boarded the parterre (the field in front of the Queen's House). What the 'mark' was is not clear. Was it something that was placed on the hillside, or was it the Castle itself?

The Royal Warrant ordering the Observatory's building

The Royal Warrant ordering the construction of the Observatory is dated 22 June 1675 and begins:

'Whereas, in order to the finding out of the longitude of places for perfecting navigation and astronomy, we have resolved to build a small observatory within our park at Greenwich, upon the highest ground, at or near the place where the castle stood, with lodging-rooms for our astronomical observator and assistant, ...' (click here to read more)

This implies that the Castle site had been cleared prior to the decision being made to site the Observatory at Greenwich.

So when was the castle demolished?

One thing that we can be sure of is that the Castle had been demolished prior to any decision being made in 1675 to build the Observatory at Greenwich. Although John Evelyn (1620–1706) mentions the Palace, the Queen's house and Castlehill in his diary, he makes no mention of the Castle itself. Schellinks on the other hand records that in 1661 the castle was a ruin and had 'been raised to the ground by the parliamentarians’. However, no other account has been found that corroborates this.

The obvious interpretation of Pepys's 1662 diary entry: 'I walked into the Park, where the King hath planted trees and made steps in the hill up to the Castle’, is that the Castle was intact. However, at the present time, we refer to both intact castles and castle ruins as castles (very little remains of Hastings Castle for example). Pepys may therefore have been referring to ruins.

The most likely scenario seems to be that the Castle was in a ruinous state in 1660 when Charles II was restored to the throne and that it was demolished at some point between 1667 and 1675.

Surviving parts of the Castle

In his letter to Towneley dated 22 January 1675/6, Flamsteed included a description of the Observatory together with a hand drawn floor plan that showed the ground and first floor of Flamsteed House, but not the basement floor, together with the relative location and floor plan of the Quadrant and Sextant House, writing:

'It were much to be wished our walls [of Flamsteed House] might have been Meridionall [aligned north/south] but for saveing of Charges it was thought fit to build upon the old ones which are some 13o½ false and wide of the true meridian as you will find by the wall of the Watch House [Quadrant House]' (RS/MS243/12)

The earliest plan of the Observatory that shows the basement of Flamsteed House and the walls of the Castle to which Flamsteed referred is Airy's plan of 1846 (ADM140/426). What it clearly shows is that the walls of the basement level are considerably thicker than the majority of those of the ground and first floor above.

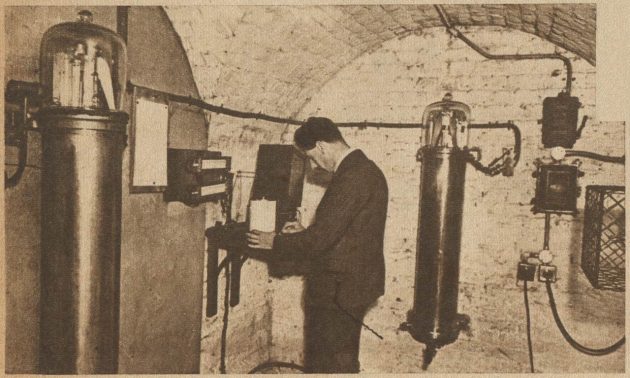

In Flamsteed's time, both the basement and first floor of Flamsteed House were roughly square in shape, with each floor being divided into four square spaces of roughly equal size. The east west dividing wall was a similar thickness at basement level to the external walls, whilst and the north south dividing wall was thinner. The north-east quadrant is shown as a pair of linked cellars running in an east-west direction which were entered from the west. Although both cellars had vaulted ceilings, none of the other rooms in the basement are thought to have had them. In 1846, the other three spaces were used as follows: Larder (north-west quadrant), Back kitchen (south-west quadrant) and a bath room (south-east quadrant).

In 1924, the inner (eastern) of the two cellars was used to house the master pendulum of the Observatory's new sidereal standard clock, Shortt 3, which was bolted onto the east wall. In 1926, it was joined by the master pendulum of Shortt 11 which was mounted on the south wall. The bolts which held it in place passed all the way through the wall. which was recorded at the time as being 3 feet 7 inches (1.09m) thick. In 1933/4 the adjoining cellar was converted to house more Shortt Clocks. This involved rendering the walls and ceiling and installing a new concrete floor. Click here to read more about the Shortt Clocks at Greenwich.

The first clock Cellar at some point prior to 1936. The clock on the left is mounted on the east wall and is the Shortt 3 master pendulum. That on the right is on the south wall and is Shortt 11 master pendulum. From the 24 February 1946 edition of Le Patriote Illustré

The second Clock Cellar in 1935. The clock is the master pendulum of Shortt 16. It is on the south wall. The handle of the door leading into the cellar can be seen on the right. The passage leading to the inner (first) cellar is on the left. © BT Heritage. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) licence (see below)

Surviving underground structures that may be associated with the Castle

As well as the walls in the basement of Flamsteed House (none of which are on public view), other elements of Greenwich Castle are thought to survive below the ground elsewhere on the site, though none of the can be dated with any certainty. They are:

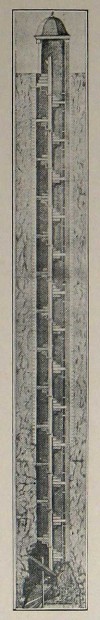

1. The well where Flamsteed constructed his Well Telescope.

Flamsteed's Well Telescope. From Webster's Greenwich Park its History and Associations (London, 1902)

The site of Flamsteed's Well Telescope (bottom) in June 2009 following a major re-landscaping of the Meridian Garden

2. An arched-over 'cellar' immediately to the north of Flamsteed's Sextant House

In the mid 1960s when the Meridian Building was being converted for museum use, what was described as 'an arched-over cellar' was discovered just to the north of Flamsteed's Sextant House. Although the brick arch was photographed for the museum records (Neg. Nos. A8027-B4 & A8550E), no description of the space has been located. However, it is worth mentioning that the arched over structure looks more like the outside of a well lining. It is not known if the 'cellar' was subsequently filled in or if it will be investigated when the Sextant House is demolished as part of the Museum's 'First Light' project.

3. A culvert and a water cistern of unknown date under the lawn to the rear of Flamsteed House

At present, the date when these two features were constructed can only be speculated upon. When in 1955, detailed plans started to be drawn up to convert Flamsteed House for Museum use, it became apparent that there was nowhere to place a central boiler … except perhaps in the Garden House, which had the added convenience of being connected to Flamsteed House by a culvert that would be ideal for carrying the pipes (WORK17/374). Why and when this culvert was constructed is a complete conundrum as its location is not shown on any known Observatory plan. However, a short section leading northwards from the Garden House (which still exists and is about 4m below the level of the garden) and a structure labelled as a 'dry drain' are shown on Airy's plan No. 1 of 1846 (ADM140/426). The latter may have been later extended to form the current passageway under the garden that runs southwards from the void area to the rear of Flamsteed House and is now full of cables which are hidden behind a doorway. There is no mention of the culvert it in the Reports of the Astronomer Royal which cover the period from 1835 onwards. One suggestion is that it was an escape route into the Park from the Castle. Another is that it provided a short cut to the garden house and later stables.

Prior to June 1821, which was when the Observatory started to obtain its water from the Kent Water Works Company (RGO6/1/55), the inhabits of the Observatory and the earlier Castle had to rely on other sources for their water. It doesn't seem to have come from a well.

Apart from the well of the Well Telescope, no other well from the seventeenth century of earlier has been recorded on the site. Although the well of the Well Telescope was dry in Flamsteed's time, it is possible that it may once have been deeper and supplied the Castle with water. We do know for certain that the Keeper's Cottage which was located about 300 metres to the east of the Observatory had a functioning well. Formerly known as The Lodge and predating the Observatory, it was demolished in 1853. An undated well (possibly dug in the 1660s when the Dwarf Orchard was created) still exists in the north-east corner of the Park in the area now known as the Queen's Orchard. There is also a reference to wells being dug in the Park in the year 1619–1620, though one of these was probably a snow well – a place were snow could be stored (E351/3253). In later years when a well, over 120 feet deep, was dug in 1815 in the Observatory's newly enclosed lower garden, 'The water proved bad, and the well was covered in' (see also RGO6/1/54). Two other wells were later dug in Airy's time, but these were not for water, but as dry wells for other purposes

It is worth noting that on the Traver's Plan of 1695–97), whilst conduits for the supply of water to Greenwich Palace are shown within the Park on the slopes of One Tree Hill (previously known as Five Tree Hill) and Crooms Hill (formerly known as Crum Hill), none are shown on Flamsteed Hill (previously known as Castle Hill).

Unless there is a yet to be discovered well on the Observatory site, it would seem that the inhabitants of the early Observatory and possibly the Castle had to rely on water collected and stored on site, possibly supplemented by other supplies carried in from outside. We know that prior to 1790 (when the Board of Ordnance supplied two lead cisterns), there was an underground cistern just to the south of Flamsteed House. The earliest known reference is a sectional plan by John Evelegh (RGO101/2/2) which dates from about 1760. It is possible that the cistern was constructed in about 1750 when Flamsteed House was extended for James Bradley. On the other hand, it could be considerably earlier. It appears on several Observatory plans including that of 1831 (RGO6/45) and Airy's plans from 1846 (ADM140/426). Both plans also show a second cistern that was demolished when the ground under the east side of Flamsteed House was excavated to create a basement in 1911. Built from brick, the one to the south of Flamsteed House was 'rediscovered' during landscaping works in 2009. The opening at the top is now covered with a modern metal inspection cover.

Acknowledgements

The images from the British Museum are reproduced under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license, courtesy of the The Trustees of the British Museum. All have been further compressed for this website.

Museum Number: 1856,0607.5 (detail)

The 1912 copy of Moore's map of 1662 is reproduced at reduced size from the digitized copy on the Yale University Library website (Call Number: 32 L84 1662/1912)

The second photograph of the Clock Cellar is © BT Heritage. It has been obtained from The BT Digital Archives and is reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) licence. It is more compressed than the original.

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan