…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

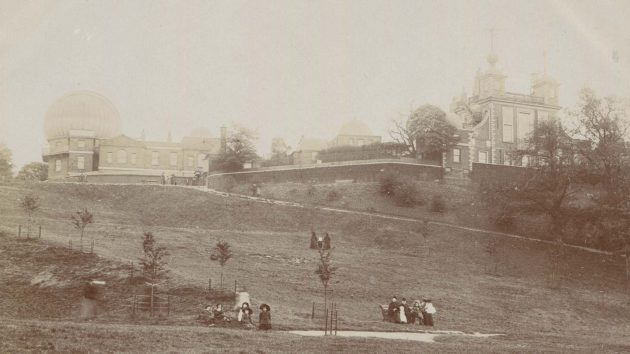

The Royal Observatory and the Giant Steps (the Grand Ascent)

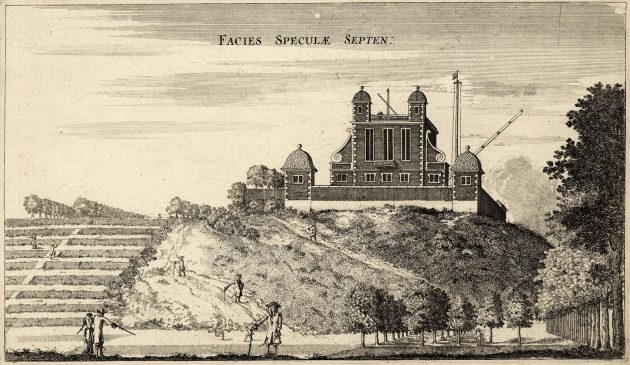

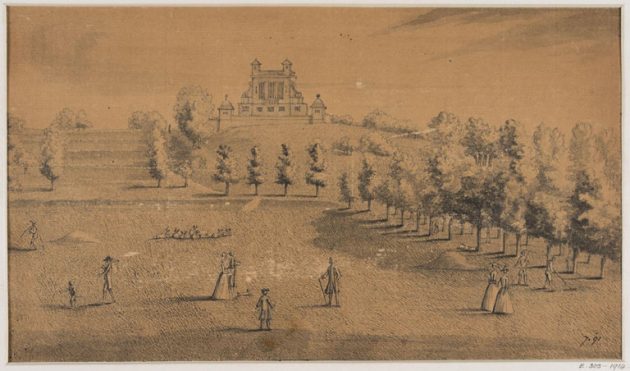

The Giant Steps (left) and the newly built Observatory (right). Facies Speculae Septen (North face of the Observatory), etching by Francis Place after Robert Thacker, c.1677. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.949

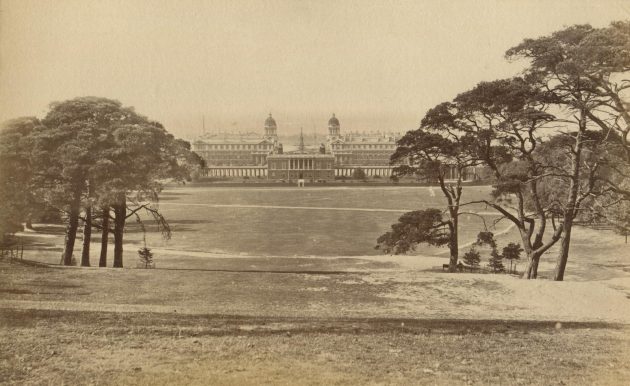

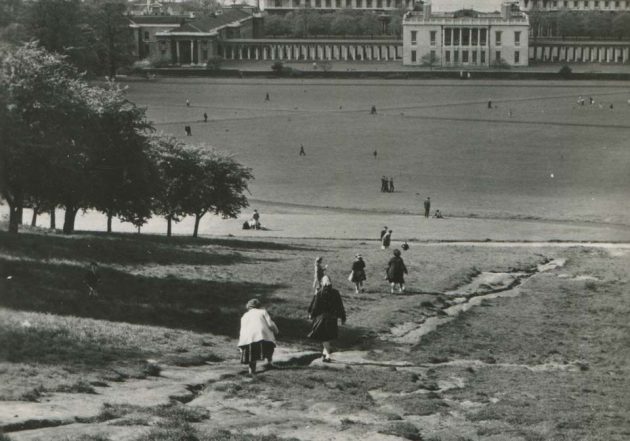

By the time this shot was taken from the grounds of the National Maritime Museum on 4 February 2009, just five steps were still visible. Also visible is the south embankment of the Parterre that ran beneath them (more on this below)

A brief summary of the Steps from the time of their creation to the present day

Greenwich has a long connection with Royalty. Henry VIII was born in the Tudor Palace, as were his two daughters Mary and Elizabeth. Construction of the Queens House began in 1616 and was completed in 1635 for Queen Henrietta Maria, the wife of King Charles I. Bridging over the London to Dover Road, it provided, for the first time, a direct connection between the Park (which had been created in 1433) and the Tudor Palace.

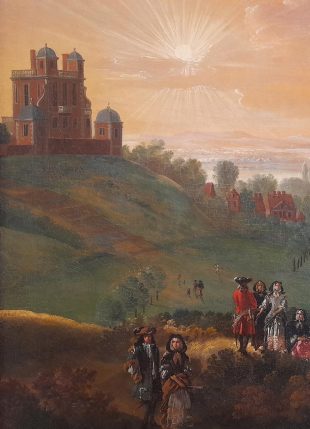

Charles I and Henrietta Maria with a group of courtiers in Greenwich Park in about 1632. The group are standing at the top of the hill near the Castle with the partially completed Queen's House behind them. From a photograph taken by the National Maritime Museum of a painting by Adriaen Van Stalbmt & Jan Van Belcamp in the Royal Collection and reproduced in George Chettle's monographThe Queen's House, Greenwich (c.1937). A link to the full colour version (RCIN 405291) on the Royal Collection Trust website is given below

Royal Collection Trust: RCIN 405291

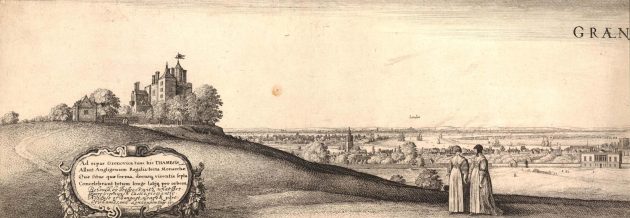

Detail from Wenceslaus Hollar's long view of Greenwich. Greenwich Castle can be seen on the left and the now completed Queen's house on the right. The etching was printed from two plates joined down the centre – a slightly cropped version of the left half being shown here. First published in 1637, this version (or state) was published in 1644 or after. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1880,1113.5510 (see below)

Following the execution of Charles I in January 1649, Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector, with the monarchy eventually being restored when Charles II returned from exile in 1660.

The 1660s were a hive of activity in and around the Park. In 1661, Charles II ordered the demolition of the now derelict Tudor Palace. John Webb was commissioned to design a new one and repair and enlarge the Queen’s House. Work started on the Queen’s House in August 1661 and on constructing the new Palace (now the Old Royal Naval College) in 1663. In 1661, work also began on re-landscaping the Park under the supervision of William Boreman. The following year, Pepys recorded in his diary entry of 11 April:

‘At Woolwich, up and down to do the same business; and so back to Greenwich by water, and there while something is dressing for our dinner, Sir William [Penn] and I walked into the Park, where the King hath planted trees and made steps in the hill up to the Castle, which is very magnificent.’

Six months later, the Dutchman William Schellinks also noted the steps in his journal, recording in the entry for 25 October 1662:

‘On the hill in the park behind the [Queen’s] house two avenues of trees had been planted from the bottom to near the top of the hill, where it was too steep to climb up, steps had been cut into the ground to walk up in comfort.’

The steps that both Pepys and Schellinks referred to were a series of grass terraces or ‘ascents’ which later became know as the ‘Giant Steps’. Directly in line with the centre of the Queen's House, they formed part of a grand axis about which the park was to be transformed from a place used for hunting to a park and garden in the French style to rival those of France. Although no plans or other records of their work survive, it is suspected that the two Frenchmen, André and Gabriel Mollet were involved in the early stages of the Park's redesign as there is a warrant from August 1661 that refers to them as the 'designers of all his [the King's] gardens for altering them and making them into the neatest formes'.

Andre Le Nôtre (1613–1700). Bronze copy made in 1913 by Adrien-Aurélien Hébrard from the original marble bust by Antoine Coysevox on the tomb of Le Nôtre in l'église Saint-Roch, Paris. Photographed October 2012 in the Jardin des Tuileries. Louvre inventory number: TU 108

In May 1662, André Le Nôtre (who was designing the gardens for Louis XIV at Versailles), was asked to contribute to the designs. The only record of his input however is an annotated plan for a Parterre on the more level ground between the Queen’s House and the bottom of the Giant Steps (now often referred to as the Queen's field). Whether this was a new feature or a modification of a parterre designed by the Mollets is not known. As proposed, it was to have a large circular fountain at its southern end centred on the grand axis and two smaller octagonal fountains near the Queen's House symmetrically located on either side. In the event, the plan was abandoned, but not before the area had been levelled and the earth banks on either side and at the southern end had been constructed and avenues of trees planted on the eastern and western banks. Also abandoned, were plans to build a water cascade down the Giant Steps. The southern and western banks of the Parterre, the latter with its trees, can be seen (bottom right) in the etching at the top of the page.

In 1886, in the first (and only) volume of his updating of Hasted's History of Kent, Henry Drake gives the following commentary about the setting out of the park in a footnote on p.66:

'Boreham's account of expenses for planting Greenwich Park between 1. Sept. 1661 and 10 June 1862, exhibit for fourteen copices, elms, birch, quicksetts, ivyberries, and holyberries, digging, trenching, planting and sowing berries, £128 16s. For seven walks - 600 elms, chestnut trees from Lesnes Abbey, grubbing, digging, making poles, fencing, watering, £92 14s. 0d. Twelve ascents, making them from bottom to top of the hill, filling part of the great pit, cutting and carrying turf, £249 12s. 6d. John Smith overseeing the workmen, 30 weeks at 12s., £18. Total, £543 2s. 6d. ... According to two privy seals, he received £888 9s. 7d. in 1661-2 for planting the park and building a keeper's cottage, ... he brought turf from the heath [Blackheath] to form steps up the hill to the castle ... '

A study of historic maps, paintings, prints and photographs suggests that over time the steps were repaired of rebuilt, their number seemingly being reduced to just five or six. By the start of the twenty-first century, although much eroded, traces of a few Steps were still visible as was the outline of the Parterre, which was still demarked by rows of trees – albeit not those originally planted.

Meanwhile, back in the 1980s, Land Use Consultants (LUC) had been commissioned by the Directorate of Ancient Monuments and Historic Buildings (DAMHB) to conduct an historical survey of the Park. Published in 1986, their study included several references to proposals from the 1950s onwards, for the reconstruction of the Giant Steps – none of which came to fruition.

The earliest dates from 1953 and mentions a 'Survey of Greenwich Park – with a view to restoring the steps and the terraces'. In 1954, following the appointment of a new Superintendent of the Park consideration of any restoration scheme was postponed until a report for the [Advisory?] Committee on Forestry, whose first report seems to have published fairly soon afterwards.In 1964, the seventh report of the Advisory committee on Forestry titled Trees in Greenwich Park was produced for the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works (which was responsible for the Park until 1970). It made a series of recommendations that included the restoration of the Giant Steps.

Finally, in 1970, a firm proposal to restore the Giant Steps in time for Easter 1975 for National Heritage Year was in hand with the appointment of Shepheard & Epstein to do the design. According to (LUC) their proposal was for 'a "modern interpretation" of the 17th century concept with '8 terraces and 9 slopes, a broad flight of steps on each side and a viewing platform at the top. Shepheard also proposed reinstating the lower terraces [presumably those around the parterre] and removing the paths that ran across them. In June 1973, the proposals were put on display in the Queens House. That some year, work on the Steps was 'postponed because of escalating costs' with just the the new viewing platform scheduled to go ahead. It is hoped to write more about this scheme as an appendix at a future date. The catalogue of Shepheard's archive can be viewed here.

Over 40 years later, in December 2017, the Royal Parks were awarded a grant (£282,600) by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Big Lottery Fund under the 'Parks for People' grant programme to work out the detail of its 'Greenwich Park Revealed' project to restore the historic landscape, improve visitor facilities, and provide more opportunities for volunteering, learning and work experience.

Some fifty-five years after the 1964 report was published, a planning application was finally submitted to the Royal Borough of Greenwich on 13 December 2019 to improve the Park and reinstate some of the seventeenth century features, including the Giant Steps and aspects of the Parterre. On 15 January 2020, the Royal Parks issued a press release stating that a (further) grant of £4.5million (£4,517,300) had been secured from the National Lottery Heritage Lottery fund and the National Lottery Community Fund towards the total cost of Greenwich Park Revealed whose total projected cost was stated as £10,500,000. A later announcement of the Park's Facebook page gave the total cost of the project as £12,000,000.

This piece, which was written in 2024, explores how the visual relationship between the Ascent and the Observatory has changed over time by examining:

- The impact on the Steps of the two expansions of the Observatory site in 1791 and 1813

- When and why the rows of trees at the end of the steps were first planted and when they were subsequently replaced

- How the Steps changed over time and whether this was a result of erosion or reconfiguration

- How the grand axis with its newly recreated steps compares with what is known about the seventeenth century designs that were originally executed.

The following two planning applications lodged with Royal Borough of Greenwich are relevant to the reconstruction of the Giant Steps.

Reference |

Detail |

Approved |

|

| 19/4305/F | Various works to Greenwich Park including … landscaping and planting enhancements including the reinstatement of the Grand Ascent or Giant Steps and Parterre Banks ... |

4 Sep 2020 | |

| 23/2509/SD | Submission of details pursuant to the discharge of Conditions 8 (Giant Steps Final Details) and partial discharge of Condition 11 (Landscape Restoration Method Statement) of planning permission 19/4305/F dated 04/09/2020 | 14 Nov 2023 |

The above links time out after a while and need to be refreshed from time to time.

The intended viewpoint and the cutting of the grass

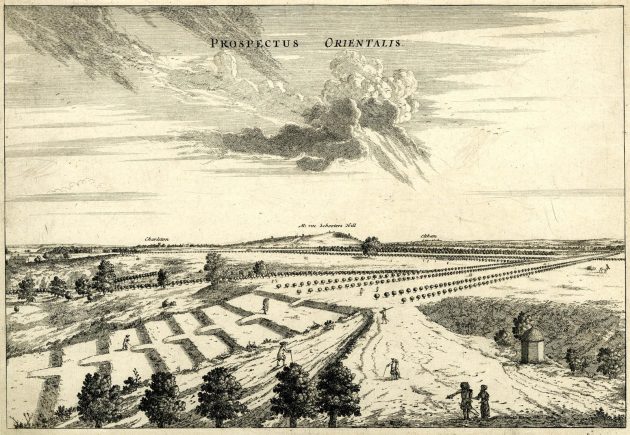

When the Queen's house was built, it had a loggia on the first floor from which members of the Royal party were able to observe hunting and other activities in the Park. The way that the Park was landscaped in the 1660s put the loggia at the very centre of things and would have provided the perfect spot to view the Parterre with its intended fountains as well as the Giant Steps beyond. The great unknown is how the steps would have originally appeared from this view-point especially as the slope of the hillside is not (and presumably was not) even. It is easy to imagine that they may have been made to have an even appearance when viewed from the loggia – a view supported by the fact that the treads of the steps are shown with different depths in the Francis Place etching below (Prospectus Orientalis), but have a uniform appearance in the Francis Place etching (Facies Speculae Septen) at the top of the page.

The Giant Steps as seen from the roof of Flamsteed House. To the right is the small building located outside the walled enclosure of the Observatory that housed Flamsteed’s Well Telescope. Note how the top step extends beyond it. Prospectus Orientalis (East Prospect), etching by Francis Place after Robert Thacker, c.1677. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.950

From private parkland to public park

A photo of the two sides of an admission ticket / key to Greenwich Park. It is stamped with the serial number 488. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: MG.718 (see below)

The Blackheath Gravels. The discarded drinks can (bottom right) gives a sense of scale. This sample was excavated from beneath a house in nearby Dartmouth Row in March 2024

According to John Bold, the pensioners from the Hospital and their relatives, together with a small number of locals were granted access in 1705 with the general public also being admitted during holidays from around the same date. However, while Bold states that the public were not given full access until the 1830s, an information board present in the Park in 2024 gives the date as 1820.

It would appear that prior to this date individuals were issued with numbered keys. Surviving examples are rare. Of those that are known to survive, all carry the date of 1733 and a serial number. An example is shown alongside. The key carrying the serial number 450 fetched £800 when sold at auction in 2014. Since no keys carrying a different the date are known, it is possible that earlier and later keys had no markings to identify them as being for the Park.

The geology of the hill on which the Observatory stands changes from top to bottom. The upper part consists of the Blackheath Beds, which are made up of a highly compacted and fairly homogeneous mix of small rounded pebbles and sand. Heavy footfall on the slopes exposes the beds which then rapidly erode as the sand washes out during heavy rain. The resulting surface can be hazardous to walk on as many an individual found out to their cost during the Greenwich Fairs which took place over several days at Easter and Whitsun.

In 1887, The Norwich Mercury contained, in a supplement, the following reprint of a piece of reporting from April 1730:

'On Tuesday last (31st) in Greenwich-Park great Numbers of People from London and the adjacent Parts, diverted themselves (as is common on public Holydays) with running down the Hill (formerly called the Giant's Steps) that fronts the Palace; but some others more venturous would run down the steeper Part of the said Hill, under the Terrace of the Royal Observatory, one of them, a young Woman, broke her Neck, another ran against one of the Trees with such Violence, that she broke her Jaw-bone, and a third broke her Leg.'

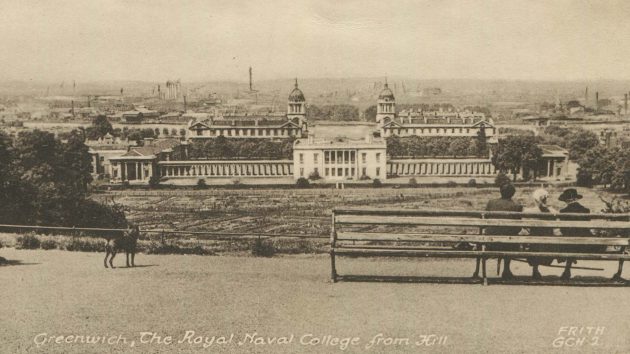

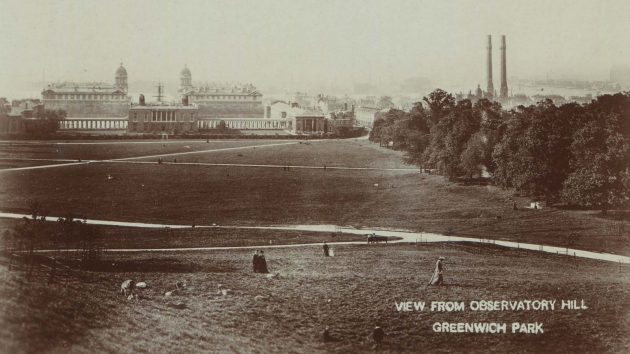

Greenwich Park with the Royal Observatory on Easter Monday. Note the large number of people crowded onto the Grand Ascent. Engraving by J Pass after Edward Pugh: published 20 April 1804 by Richard Phillips

The problem of erosion caused by visitors to the park was recorded by the Astronomer Royal, George Airy, in his 1840 Report to the Board of Visitors, where he wrote:

'Within the last year, the attention of the Civil Architect of the Board of Admiralty has been called to the state of the North Terrace wall. The wall, probably from an injudicious mode of building and from the effects of water and frost, has bulged out considerably; and the foundations, not only of the wall but also of the whole of the northern and western faces of the house and of the court-wall, have been completely exposed. This appears to have arisen from the gradual crumbling down of the steep hill, assisted as it is by the continual treading of the enormous number of persons, who, on every fine day, are walking beneath the terrace wall. The Civil Architect proposes, as I believe, to recommend that the wall be rebuilt, and that a portion of the walk below be completely paved, as the only way of preserving the foundation of this venerable building.'

From the start of the twentieth century onwards, a number of things have happened that have brought ever greater numbers of local, national and international visitors into Greenwich and the Park. They include:

- The opening of the National Maritime Museum in 1937

- The opening of the Royal Observatory to the public in the 1960s

- The celebration of the 300th anniversary of the Observatory's founding in 1975

- The centenary of the adoption of the Greenwich Meridian as Prime Meridian of the World in 1984

- Blockbuster special exhibitions at the National Maritime Museum such as Armada (1988) and Titanic (1994

- The closure of the Royal Naval College and the creation in 1997 of The Greenwich Foundation. Since then, the grounds and some of the buildings have been opened to the public whilst other of the buildings have been put to use by the University of Greenwich University and Trinity College of Music. Also in 1997, the creation of The Maritime Greenwich World Heritage site

- The global celebration of the start of the new millennium with Greenwich as the home of the Prime Meridian and Greenwich Mean time at its focus

- The equestrian events of the 2012 Olympics which took place in the Park and were seen by a global audience on TV

- The residential development that has been taking place since the millennium, in particular on the Greenwich Peninsula and West-India Docks and the rest of the Isle of Dogs which sits on the opposite bank of the River.

Over the years, the rise in the number of visitors has taken an ever-increasing toll on the fabric of the Observatory, the viewing area outside at the top of the Grand Ascent (where the Wolfe Statue now stands) and on the Ascent itself.

Although today permission is only required for commercial filming and photography in the Park, in the past the Park bye-laws required visitors to apply for a permit in order to paint or take photographs. Sometimes people wrote in error to the Astronomer Royal rather than the Park authorities to obtain one. RGO7/58 contains some of these requests. Further research is required in order to understand how and when the earlier permit system operated and its impact on the images that have come to us today.

The earliest records – the financial accounts of Sir William Boreman

Information about the construction of the Ascents is preserved in the financial accounts of Sir William Boreman at The National Archives in the following two locations:

- SP29/56 (Secretaries of State: State papers domestic, Charles II. Letters and Papers)

- E351/3428 (Exchequer: Pipe Office: Declared accounts. Works and Buildings (Miscellaneous).: Sir William Boreman. Works in Greenwich Park)

SP29/56/39&39.1 are single page documents. The first is a covering letter from Boreman that begins 'May it please yor Majesty'. The second is an unaudited breakdown of the money expended on the redevelopment of the Park between 1 September 1661 and 10 June 1662. The account is presented in three sections under the following headings:

- 14 Coppices

- 7 Walkes

- 12 Assents

It ends with a table showing the grand total, the money already advanced and the remaining money due. A provisional transcript of the section relating to the Ascents reads as follows:

12 Assents

| ffor dayes worke and taske worke in making the Assents from the bottome to the topp of the hill, filling parte of the great pitt, cutting and carrying of turfe, and for moweing & keeping of them as by the pticulo [particulars?] in the Account it appear |

249: 12: 06 |

|||

| To John Smith for setting out the Worke of the Coppices Walkes and Assents, and for overseeing the Workemen for ye Space of thirty Weekes at 12s the weeke | 18: 00: 00 |

E351/3428 is a rolled parchment document consisting of two sheets written on both sides and stitched together along their top edge. It contains Boreham's certified accounts for the period 1 September 1661 – 10 June 1662. Not only are these more detailed than those in SP29/56, but the money is accounted for differently. Spellings are different too. For example John Smith's name is spelt Smyth. Of greater significance however is the fact that the stated number of Coppices and Walkes is different too (more on this later). The numbers recorded in the document are:

- Coppices: 16

- Walkes: 4

- Ascents: number not specified

A provisional transcript of the sections relating to the Ascents reads as follows:

| [From the section relating to the Coppices] | ||||

| The sayd John Smyth and Richard Nightingale for somuch by them payd Sundry Labourers at xvid the man p diem imployed in taking down ye banks at the Ende of the Ascents, throwing down and Levelling the Ditch bankes before the holes could bee made up, making some good ground and filling good earth into the Carts to bring to the trees and putting it under the rootes of the Trees at ye planting of them and for putting brakes[bracken?] about the rootes to defend them from the weather, with other neccie [necessary?] works there. In all. |

xlviii£. xviis. [£48.17s.0d.] |

|||

|

[From the section relating to the Walkes] |

||||

| And to Richcard Dorey for Moweing the walke between the Queenes house and Ascents according to Agreement |

xiis. | |||

|

[From the section relating to the Ascents] |

||||

| John Smyth Gardiner for somuch by him payd for cutting of xxvi acs of thyn Turfe upon Blacke-heathe at xviiid p C [26 acres at 18d per square chain, ie 0.1 acre] |

xix£.xs. [£19.10s.0d.] |

|||

| The sayd John Smyth for somuch by him likewise payd to sundry workmen and labourers imployed in digging, levelling, bresting[?] and turffing the severall Ascentes up the greate hill and makeing and turffing the Staires from one Ascent to another and doeing other services prtinent thereunto. |

cxlvi£.iis [£146.2s.0d.] |

|||

| William Wilby, Thomas Swift and John ffisher for fetching of Trees from Leezen [Lesnes] Abby at xiis p. load [,] Eltham and other places at viis per load, for as c/iiii xlv [ie ccccxlv – 445] loads of earth to put about the rootes of the Trees at vid p load and for all other woorke done by them with theire foure Teames about the Trees & Ascents during the whole time of this Account at vis p diem for each Teame. In all. |

xx/iiii£.viiid [£80.0s.8d.] |

|||

| And to John Carter for Moweing and Rowleing the Ascents and for lookeing to them by the space of vi weekes at xs p weeke |

lxs [£3.0s.0d] |

|||

| In all the sayd Charges for the makeing and Turffing the Ascents up the greate hill As by the sayd booke of Account delivered upon Oath as aforesayd and several arquittances of the partyes who received the sayd moneys hereupon examined and remayneing likewise appeareth the sume of |

ccxlviii£.xiis.viiid [£248.12s.8d.] |

|||

|

[From the section relating to sundry other expenses] |

||||

| To John Smyth Gardiner for setting out the worke and overlookeing and paying the workemen for the space of xxxty weekes within the time of this Account at xiis p weeke. |

xviii£. [£18.0s.0s] |

The section devoted to the Ascents clearly contains charges such as the fetching of Trees from Lesnes Abbey and Eltham that should have been placed in a different section of the accounts. Why they weren't can only be speculated upon. Of particular interest is the cutting of 26 acres of turf on Blackheath. The Ascents themselves have an area of about one acre. So where did the other 25 acres go? There are three possible explanations. Either they were

- used elsewhere in the park (perhaps in the construction of the 'Walkes'), or

- they were used to build up the Ascents by layering them one on top of the other, or

- they were used for both the above.

The first scenario seems unlikely, as if this was the case, the charges would presumably have been placed under a different heading. The second or third scenarios seem the most likely. Building with turf is a proven technique that was used by the Romans when building earthen walls and ramparts, the roots contained within the turf helping to keep the soil particles connected to one another. The findings from bore-holes 2 & 8 which were sunk on the east side of the Ascent in April 2022 (see 23/2509/SD, Civil engineering stage 4 report p06-part-1, pp.34–42) show the presence of rootlets and root hairs at depth, but there appears to have been no analysis to determine if they came from turf or from the later plantings of trees.

The natural slope of the hill cuts diagonally downwards across the Ascents from the west to east. Boreman's accounts record that digging took place during the creation of the Ascents, which suggests that they may not have been constructed from turf in their entirety. It is surmised instead that the risers were built up from turf and the eastern side of the treads back-filled with material dug out from the hillside on the western side and elsewhere.

As well as Boreman's accounts, for the period ending 10 June 1662, the National archives holds his accounts for the period 1662-1665 (SP29/116/14) and the certified accounts relating to the Park for the period 1663(?)–1670(?) that were presented by Hugh May on behalf of his recently deceased brother Adrian May. The latter can be found in the following two locations: E351/3431 & AO1/2481/292. Neither of these two documents makes any reference to the Ascents. The first is written on parchment. The second is written on paper and appears to be a duplicate copy of the first (though there is at least one unimportant difference). When Hasted wrote his footnote (above), he had clearly taken a look at all the Boreman documents and at least one of those relating to May.

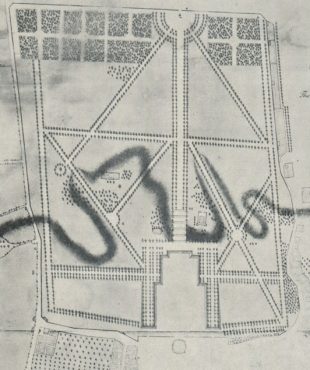

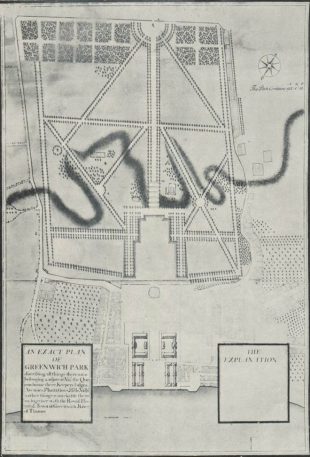

Plans that show the steps

There are no known plans of the Park prior to 1660. Although there are many known later plans, apart from the Stanford's plans published in the second half of the nineteenth century, only the earliest of these show the Giant Steps.

Date |

Plan |

Number of risers |

Trees at the end of treads? |

||

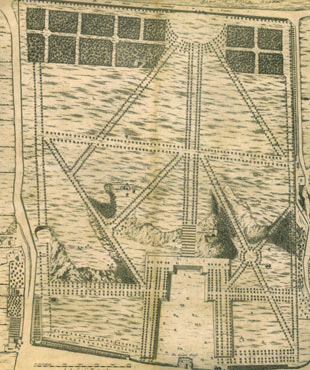

| c.1677 |

Although often referred to as the 'Pepys Plan', this plan is believed to be one of the etchings done for Flamsteed by Francis Place. On this page it is referred to as both the Pepys Plan and the Francis Place Plan |

12a | No | ||

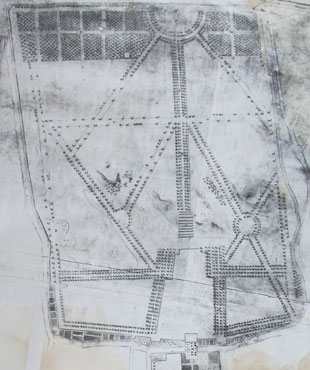

| 1693 | Said to have been drawn by Joel Gascoin and housed at the National Archives (MR1/329) this plan carries the title: An Actual Survey of the ground wereon their Majesties antient Palace at Greenwich (in the county of Kent) formerly stood ... | 10 | No | ||

| ?1695++ | The so called 'Woodlands Plan' |

7a | Nob | ||

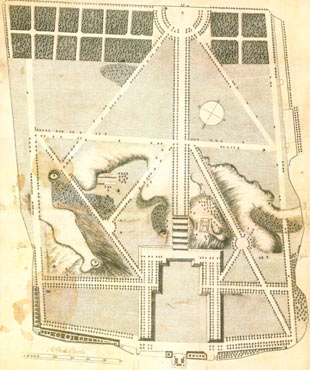

| ?1714 | An exact Plan of Greenwich Park ... . Said to have been produced by/for the Royal Gardener Henry Wise (1653–1738). |

6 | Yes | ||

| 1862 | Stanford’s Library Map Of London And Its Suburbs | 6 | Yes | ||

| 1872 | Stanford’s Library Map Of London And Its Suburbs | 6 | Yes |

Footnotes:

a) Extracts from these plans showing the Grand Ascent can be seen in the document titled Written Scheme of Investigation for the Grand Ascent ‐ September 2023, which was deposited as part of planning application 23/2509/SD to the Royal Borough of Greenwich. Low resolution copies of the complete Pepys and Woodlands Plans are reproduced in the Greenwich Park conservation plan 2019–2029 (p.39). The same document also has a copy of the 1850 Sayer Plan (p.42) which is referred to later. A low-resolution copy of the Woodlands Plan is also reproduced on p.11 of the Design and Access Statement submitted as part of planning application 23/2509/SD

b) On this plan, the ends of each tread are marked with triangles as is the southern embankment of the Parterre immediately to the east and the west of the bottom Giant Step. Although they may signify the presence of conifers, their exact meaning is unclear as there is no key to the symbols

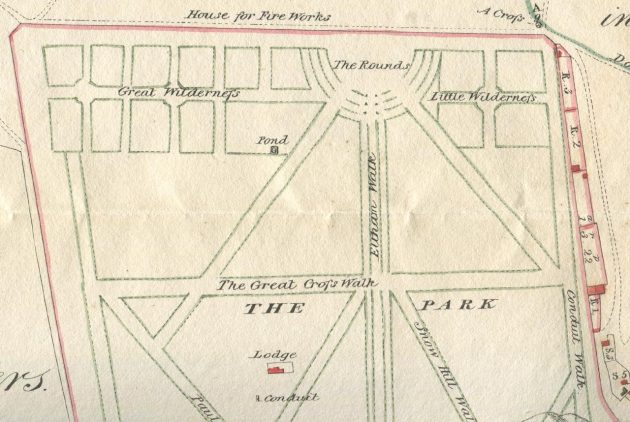

Only two copies of the Pepys Plan are known to survive. One is held by the Pepys Library in Cambridge. The other was discovered by Derek Howse in the collections of the Greenwich Local History Library (which was later merged with the Borough Museum to form the Greenwich Heritage Centre which was later reconstituted as Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust). The Plan is an unusual hybrid of plan view and bird's eye view, the viewpoint for the latter being an imaginary elevated position to the north of the Queen's House which is at the bottom. The Parterre is shown in perspective view and for this reason, the east and west Parterre banks do not run parallel to each other as might otherwise be expected.

The catalogue entry for the 1693 Plan states it was drawn by Joel Gascoin (Gascoyne?). Although his name does not appear to be present on the Plan itself, the form of the compass rose is similar to those on other plans he is known to have drawn. It also has a typically elaborate Cartouche.The Plan has misshapen features in common with the Samuel Travers Plan of 1695/7: the Parterre on both having been drawn lopsided and not properly centred on Blackheath Avenue. It would seem therefore that Travers copied some elements from the earlier plan.

The Woodlands Plan came to the Borough of Greenwich in the early 1970s from the collection of the Blackheath antiquary Alan Roger Martin. It is the only known copy and is now in the care of Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust. Its earlier provenance is unknown as is the surveyor, purpose, date and meaning of some of the symbols used. It was labeled 'Woodlands Plan' by Land Use Consultants in their 1986 report on Greenwich Park as a way of identifying a nameless plan and the name has stuck. It takes its name from Woodlands House which is where the Local History Library was located at the time. The presence of the 'New Road' at the bottom of the Plan (cropped in the copy below) suggests a date of 1697 or later.

There are three key differences between the Pepys Plan and the later Gascoin and Woodlands Plans that are relevant here. The first is in the number of steps which are shown. The second relates to the avenues of trees. The Pepys Plan shows all the avenues completely planted. The two later plans show lots of gaps in the avenues in the southern half of the park with the exception of the southern boundary, the main avenue from the Blackheath Gates and the 'rounds' which were adjacent to the gate (were these prioritised in order to impress visitors arriving from Blackheath?). The gaps elsewhere, whilst substantial are not identical on the two plans. The difference between them and the earlier Pepys Plan is difficult to explain. A previous theory that the losses were due to storm damage in 1703 is clearly incorrect. Other possible explanations that need to be considered include felling for timber, premature death and a further scenario that is discussed below. The third difference is in the number of coppices shown at the south end of the Park.

In each of the five plans below, south is at the top. All have been cropped – The Pepy's and Woodlands Plans marginally so, the others rather more.

Detail from the 1816 copy of the 1695 Plan by Travers. The fifteen green shapes in the Great and Little Wildernesses represent the coppices. In the earlier Pepys plan two fewer coppices are shown in the Great Wilderness. It is thought that the larger coppice containing the pond (which also appears in the Pepys, Gascoin and Woodlands Plans) was originally counted by Boreman as two coppices rather than just one.

As noted above, Boreman's unaudited financial accounts for the period 1 September 1661 to 10 June 1662 (SP29/56/39.1) state that seven walkes were constructed. The audited accounts (E351/3428) state there were four. Likewise, the unaudited accounts state that fourteen coppices were constructed whilst the audited accounts state there were sixteen. The number of sixteen is also appears in Boreman's second set of unaudited accounts (SP29/116/14) which begin as follows:

'The whole charges of keeping and planting Greenewch parke wth the 16 Coppices and dwarfe Orchard for the space of these years, beginning at our Lady day [25 March] 1662 & ending at our La:day [25 March] 1665 and building the gardenhouse.'

So why the discrepancy in the financial accounts? And why does the Pepys Plan show two fewer coppices than the later plans? Is it possible that fourteen were originally intended, but a decision was made soon after to increase the number to sixteen? This raises the intriguing possibility that the Pepys Plan was copied with some modifications from a now lost masterplan or artists impression that was drawn in 1663 or 1664 shortly after Le Nôtre became involved and that the masterplan itself was based on one of a couple of years before. This seems all the more likely as Sir Jonas Moore who commissioned the etchings from Thacker and Place was Surveyor General of the Ordnance and would almost certainly have access to any existing plans of the Park ... and why create an entirely new plan when an earlier plan could be easily adapted?

It would have been simple enough for Thacker or Place to copy the earlier plan, replace the Castle with the Observatory and scrub out the fountains from the Parterre. If this was the case, the failure to change the number of coppices from 14 to 16 requires explanation. Perhaps the exact number was considered unimportant. It is also possible, given their distance from the Observatory, that neither Thacker, Place nor Flamsteed realised that the number shown was no longer correct. Although it never happened, Flamsteed originally planned to publish all or most of the 12 Francis Place etchings in his Historia in the manner of earlier astronomers. As such, they were designed to show the Observatory in the best possible light. An earlier masterplan showing the avenues as complete would have suited Flamsteed's needs very well even if at the time of the Observatory's founding there were still many trees to be planted or re-planted.

Whilst the Thacker/Place topographical views are generally considered to be be accurate representation of what existed when they were drawn, there are unexplained inconsistencies between the two topographical views Facies Speculae Septen and Prospectus Orientalis and and the plan of the Park that was drawn to accompany them. The most obvious is that Facies Speculae Septen shows the presence of nine risers on the Grand Ascent, whilst the plan shows twelve. If the plan is based on one drawn in 1663 or 1664, and if, like the coppices, the number of steps constructed differed from the number originally planned, this could account for the discrepancy. It might also explain why the trees shown on the Parterre are not consistent with the layout on the plan (or indeed any of the later plans). Both topographical views show the presence of what appears to be a ramp in the centre of each step. These are not shown on any of the plans or in any other known images. They may have been preparatory works for the cascade that was abandoned. Alternatively, and more likely, they are the remnants of the 'Staires' mentioned by Boreham in his financial accounts. In Prospectus Orientalis, Snow Hill Walk (later called Brazen Face Walk, but now called the Avenue) has been omitted and the avenue that connects between Pauls Walk (now Lovers Walk) and Eltham Walk (now Blackheath Avenue) joins the latter short of the Great Cross Walk. We know from May's financial accounts that a great deal of earth moving was required to create Snow Hill Walk. We don't however have a precise date for when the works were completed. It may have been as late as 1670 with the trees on the avenue being planted at a later date.

There is no contemporary account in which the number of etchings completed by Place for Flamsteed is recorded. Given that there are only two known copies of the Pepys Plan, some have questioned whether it was really part of the set. The evidence that it is, is circumstantial but compelling. Firstly, when Pepys came to mount his collection of topographical prints in 1700, he mounted all the Francis Place etchings together (twelve in total), with the Title Plate being glued onto the rear of the Plan (which was folded in). More importantly, when writing to Abraham Sharp on 21 April 1721, Joseph Crosthwait (who was preparing Flamsteed's Historia for publication) wrote:

'There are about three sheets of the observations to print; which, as soon as finished, shall be sent you, with the pictures you desire. I should be glad to know whether you had ever the map of Greenwich Park, the plan of the Observatory, with the different prospects of it, sent: if you have not, I will send them, as soon as some few alterations are made in the plate of the Park.' (Baily p.343)

Although the alterations were not specified, it is known for a fact that the scale on the Pepys Plan is incorrect. It should have read ‘Scale of ‘Yards’, not ‘Scale of ‘Feet’. It is quite possible than it was also planned to change the number of steps on the Plan from twelve to nine.The Wise plan is difficult to interpret. It is undated and has two text panels only one of which has been engraved (see complete version right). It is missing the new road which had been constructed by 1697 but does show the whole of Greenwich Hospital which was not completed until 1751. The Hospital design however had been finalised by 1699. Haynes (2023) suggests the Plan was drawn for Wise by Charles Bridgeman. Further research into the dates of the buildings shown elsewhere on the plan may help date it more precisely.

First published in 1862, the Stanford's map was updated and re-issued over the following decades. Stanford's mapping of Greenwich Park is at odds with that of the Sayer's maps of 1840 and 1850 and the Ordnance Survey maps from this period. Apart from being the only mid nineteenth century map to show the steps, the trees on the eastern Parterre Banks are shown on an entirely wrong alignment.

Before leaving this section, it is worth noting that:

- The Pepys, Travers, Woodlands and Wise plans have all been drawn with the Queen's House at the bottom and the southern end of the park at the top. In this orientation, the grand axis and the view from the Queen's House is brought to the viewers' attention. A modern equivalent is the way a Sat Nav orientates a roadmap when driving so that the direction of travel is always towards the top of the screen

- The number of coppices planted was probably related to the fact that trees were typically coppiced for wood (i.e. cut to ground level and allowed to regrow) on a fourteen year cycle. On this basis, the plan would have been for one coppice to have been cut each year.

Late 17th & 18th century images showing the steps

In the late seventeenth century, three Dutch artists all painted views looking outwards from Greenwich Park. They were Johannes Vorsterman, Jan Griffier and Hendrik Dankerts. All three are credited as having painted views that include: the Queen's House, the Parterre, the Giant Steps and the Observatory. None are understood to be signed or dated. Both Vorsterman and Dankerts are said to have had paintings commissioned by Charles II.

Vorsterman, produced a number of versions of the same painting which vary slightly in detail. Copies are held by the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) and the National Maritime Museum. Both have been digitisied. The Spread Eagle Art Collection (now on display at the Trafalgar Tavern in Greenwich) has a view by Dankerts that is very similar to the Vosterman views (not digitised). All appear to capture the scene as it existed in the 1680s. Each shows the completed King Charles Block of the new palace together with the partially demolished Tiltyard Tower of the old Tudor Palace.

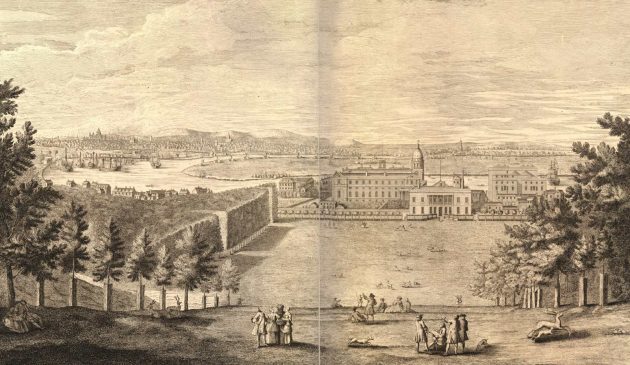

In this view from about 1680, the Observatory can be seen on the top of the hill on the left, whilst the Queen's House with the partially redeveloped Tudor Palace can be seen on the right. Note how the the path that can be seen in Hollar's view of 1637 appears to have become re-established and runs diagonally across the Parterre in front of the Queen's House (It does not however appear in the two slighly later Griffier paintings owned by the National Maritime Museum to which links are given below). Johannes Vorsterman, oil on canvas, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1976.7.112. (see below)

Griffier's paintings are slightly later as the Tiltyard Tower is in a greater state of decay. Topographically speaking, his paintings are inferior to those of Vorsterman. Not only are the views strangely distorted, but the east side of the Observatory is incorrectly shown and the towers of the medieval St Alfege, Greenwich, and St Nicholas, Deptford churches (which can be seen in the mid-distance) have been painted somewhat oversize. Despite all this, the Giant Steps are much more clearly defined than in the Vorstermans. The NMM has two copies. A third was sold by Sotherby's (Lot 41, Sotherby's sale, 30 June 2005, when it was said to be by Vorsterman. All three copies have been digitised.

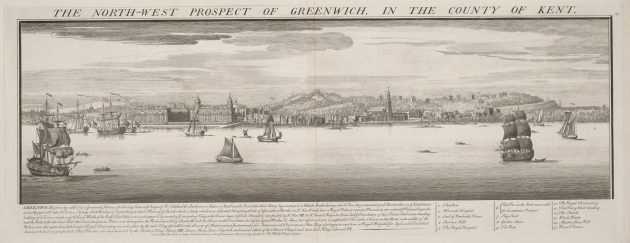

In addition to the views of Vorsterman, Griffier and Dankerts, there are three eighteenth century views that are known. The first is an engraving published in 1739 by Samuel & Nathaniel Buck. The second is a drawing by A.J. Sweate and is signed and dated 1746. The second is an undated drawing by John Charnock.

Published in 1739, four steps can be seen in this view. Samuel & Nathaniel Buck, Engraving, The North West Prospect of Greenwich in the County of Kent, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.19080. (see below)

The North Prospect of Dr. Flamsteed's house in Greenwich Park in Kent. Drawing, pen and ink on paper mounted on wood panel, signed and dated A. J. Swete, 1746. In this view four, possibly five risers are visible. Note the presence of the path on the hillside immediately to the right of the Ascent. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Accession Number 7-1891 (see below)

The table below gives details of the various images together with links to digital images that can be viewed online.

Date |

No. of risers 1 |

Artist |

(Digitised) image |

|

| c.1677 | 9 | Thacker/Place | Facies Speculae Septen (above) |

|

| 8 + (7? +) | " | Prospectus Orientalis (above) |

||

| c.1680s | 5+ | Vorsterman | YCBA (above) | |

| 9+ | " | NMM (Object ID: BHC1808) | ||

| 12+ | Dankerts | Spread Eagle Collection 2 | ||

| c.1690? | 6+ | Griffier | NMM (Object ID: BHC 1833) | |

| 9? | Griffier | NMM (Object ID: BHC 1817) | ||

| 9? | Griffier/Vorsterman | Sotherby's sale, 30 June 2005 | ||

| 1739 | 4 | Samuel & Nathaniel Buck | YCBA (below) |

|

| 1746 | 4 (5?) |

Sweate | V&A (Accession No: 7-1891) |

|

| c.1780? | 13 | Charnock | NMM (PAF 2865) |

Footnotes:

1) In the paintings by Vorsterman Griffier and Danckerts, the steps are not always very distinct. Nor is the complete flight always shown (hence the +)

2) Digital image not currently available

Taking the images together with the plans, it would appear that the number of steps decreased from the original 12 recorded in Boreman's accounts to around five by the mid eighteenth century. However, no evidence has been found to establish how, why or when this happened. Was it because some steps wore away and others didn't or was it because the steps were reshaped or reconfigured at some point?

The thirteen steps shown in the later Charnock view are problematic and difficult to explain. The NMM owns a second view by Charnock, but from a different angle, as well as several views of the instruments drawn by him. All are considered to be topographically accurate and can be corroborated. By comparison, the drawing showing the steps is rather crude. It appears to have been drawn after the summerhouses were enlarged in 1773 but before the Courtyard was enlarged in 1791. There are three ways of explaining the presence of the thirteen steps. Either there were more than five steps present when Sweate and the Buck did their drawing, but many of them were indistinct and not included, or the steps were recreated after 1746 but quickly disappeared (they do not appear in any other view), or Charnock sketched what the Observatory might have looked like if the twelve steps in the Francis Place Plan had still existed. Although the Observatory did not at that time own any of the Francis Place etchings, it is possible that Charnock had seen the set owned by Pepys, as he had volunteered with the Royal Navy and researched historical and contemporary naval affairs. His book An history of marine architecture (which he also illustrated) was published in 1801.

The planting of the trees on the ends of the treads

As noted above, the first plans that shows trees planted on the ends of the treads of the steps date from the early eighteenth century some 40 plus years after the steps were created. Despite this and the evidence of all the seventeenth century images above, Drake has been mistakenly taken to imply that they were planted from the start as seems to have been the assumption of A.D. Webster (the Superintendent of Greenwich Park) in his book Greenwich Park: Its history and associations (1902). It also appears to be the prevailing and mistaken view of the Royal Parks at the present time (2024).

The first trees to have been planted were Scots Pines and the earliest view located to date that shows them is dated 1731 and reproduced below.

Urbis Londiny Fluvy Thamesis, Templi Palaty, Viridary Greenovicensium ab Austro Conspectus engraved by Claude Dubosc after Alexander Gordon and published in 1731. Note the newly planted trees on the edge of the steps whose trunks have been encased to protected them from the deer. Note too the pleaching of the trees on the edge of the Parterre and the groups of people sitting on the top of some of the steps on the lower part of the slope. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum Number: 1880,1113.5519 (see below)

As well as not knowing when the trees were planted it is also not known why they were planted or why Scots pines were chosen as they can grow to a height of 35m with a spread of 6–12m. In the early days of their existence, the sides of the steps would have become less well defined over time, so maybe the trees were planted to help prevent erosion at the edges whilst at the same time providing (at least when they were young) a clear visual boundary that reflected the original linearity.

As the trees on the edges of the Giant Steps matured, they began to obstruct the view of London from the top of the Ascent. It was possibly for this reason that the trees towards the middle of the western row had been felled by 1840. 1842 Lithograph by Thomas Shotter Boys. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum Number: 1880,1113.5546 (see below)

Taken around 1880 (between 1873/4 and 1884), this photo shows one of the pines outside the Observatory gates. The date a fence was first erected at the top of the Ascent has yet to be established, but was possibly in the mid 1850s. It was changed for one of a different design in about 1890. Albumen Print

Thought to have been taken by the same photographer on the same day as the shot above, this photo shows the pines at the bottom of the Ascent. Several trees have been replaced with new plantings. Note the bare area on the right where a broad path ascends the Ascent. Albumen Print

Webster says of the trees:

'The terraces were forty yards wide, and planted on either side with a row of Scotch fir trees, which were brought from Scotland by General Monk, in 1664. These trees were planted twenty-four feet apart, and in continuation of the outer lines of those forming the Blackheath Avenue. As late as forty years ago the lines of fir were quite complete, the gravelly soil and airy situation having been conducive to their rapid growth and perfect development, for we find that many of the stems measured four feet in diameter at ground level. With the impurities of the atmosphere, which have become very pronounced during the past half-century, the Scotch pines gradually gave way, and the last were felled about eight years ago [i.e. in 1894].'

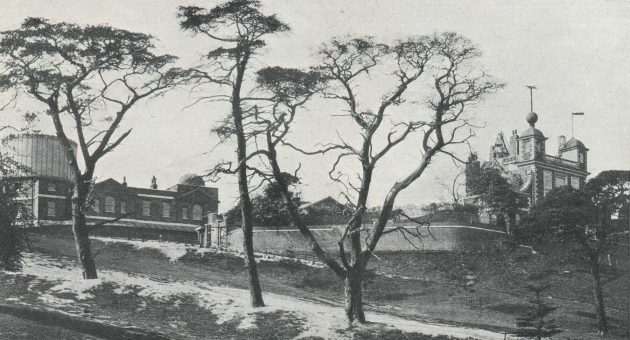

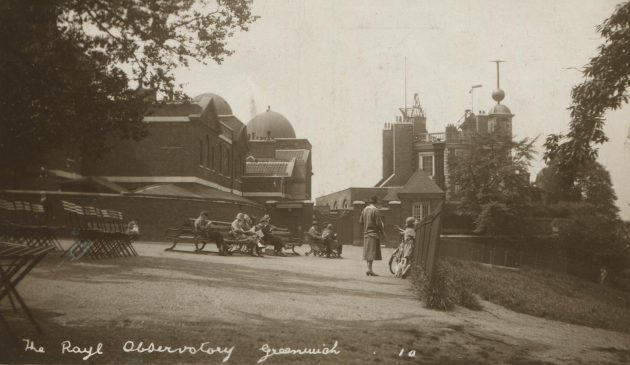

Probably taken in about 1890, the decayed state of the Scots pines on the outer edge of the Grand Ascent is clearly visible. On the west side (closest to the Observatory), four recently planted Scots pines can be seen. One recent planting is also visible on the east side. To protect the new trees from the deer (which at that time still roamed the whole of the Park), they were enclosed by metal fencing, each panel of which has five horizontal rungs. The enclosures on the east side consist of four such panels whilst that on the east side is made up of six. The original glass plate from which the image is taken was, and probably still is, in the Observatory archives (now at Cambridge). The image as reproduced here has been taken from Hutchinson's Splendour of the Heavens (1923) where a large erosion channel with near vertical sides as much as a foot or more deep was cropped from the bottom edge

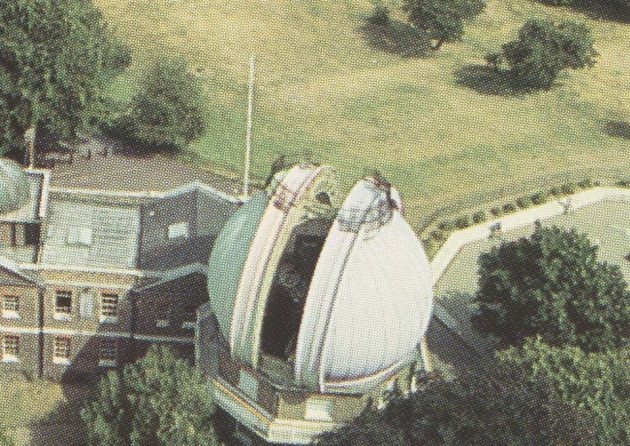

When this shot which was taken, all the old pines bar one on the western side of the Ascent had been felled. What look like stumps can be seen to the left of the tree still standing. Note the otherwise unrecorded presence of a path rising diagonally across the Ascent and passing behind the large pine. Given that the Great Equatorial Dome was completed in April 1893 and Webster seemed to think all the pines had been felled by 1894, it seems likely that the photo was taken in 1893/4. Albumen print published by the London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company

Apart from being wrong about when the trees were planted, Webster is also wrong about when they began to be felled, which was somewhat earlier than he states as can be seen from the photo in the Royal Collection to which a link is given in a later section as well as in paintings and engravings from the 1860s. Perhaps this is because he ignored the images and relied instead on the 1867 survey carried out by the Ordnance Survey, which seem to have stylised and incorrect representations of where the trees were on the Ascent.

What Webster also failed to say was that some of the felled trees had been replaced by young trees of the same variety (as can also be seen in the images immediately above) and that these too were removed. For several years there were no trees on the slope. The photographic evidence suggests that during their absence the ground was smoothed over, probably by the addition of new soil from elsewhere. Two rows of trees were eventually replanted in the winter of 1903/1904. They are all believed to have been hawthorns.

Taken between about 1900 and 1903, this shot captures the period after the clearance of the Scots Pines but before the planting of the hawthorns. Detail from a postcard published by H. Howard, Greenwich / Madame Hansford, Greenwich

The newly planted trees surrounded by their protective metal barriers in about 1908–09. Three risers can be clearly made out in the lower half of the Ascent, with two more just about being visible in the top half. Note too the contouring of the hillside where it falls away to the east of the eastern (left-hand) row of the newly planted trees. Detail from postcard number 3609 by Card House

A second view from a year or two earlier, but this time looking across the Ascent. The scaffolding on the roof of Flamsteed House suggests a date of 1907. Detail from a postcard attributed to C.W. Green, Plumstead

Over the years, the hawthorns disappeared, the last ones being removed at the end of 2023 when work started on recreating the six steps (six risers and five treads) and planting the new hawthorns for which planning permission had been given. By the 5 February 2024, the heavy ground works necessary to create the new steps was nearing completion and several of the new trees had been planted. However, rather than being planted according to the approved plan in line with the pre-existing inner rows of trees in Blackheath Avenue, they were planted in line with the newly planted inner rows of trees on either side of the Wolfe Statue, which are offset inwards by around a yard from the alignment of the rest of the trees in the avenue. The end result is that the actual separation of the lines of trees on the steps is roughly half of what is was in the previous two plantings.

The re-created steps with their eight hawthorns photographed from the entrance doors of the Queen's House on 25 March 2024. The Wolfe statue at the top of the steps closes the view and was erected in 1930 (more on this below). Due to the shallow angle of its slope, the third (middle) tread is almost hidden from view

The impact of the Observatory expansion on the upper steps

The Observatory from the east before the Courtyard was enclosed in 1791. Bradley's 'New Observatory' (now part of the Meridian Building) sits behind the wall in the shadow on the left. Thought to have been painted in the 1780s, the artist was recorded by Margaret Maskelyne as Mr S[?]inley'. Watercolour reproduced courtesy of The Petersfield Bookshop

Detail from the plan of the Observatory grounds as they existed in December 1846 showing the eastern extent of the enclosures of 1791 and 1813. Modified from the plan published in the 1845 volume of Greenwich Observations. Reproduced courtesy of Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek under a No Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Only license (see below)

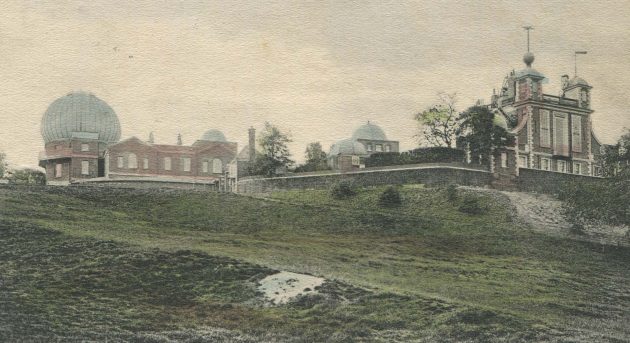

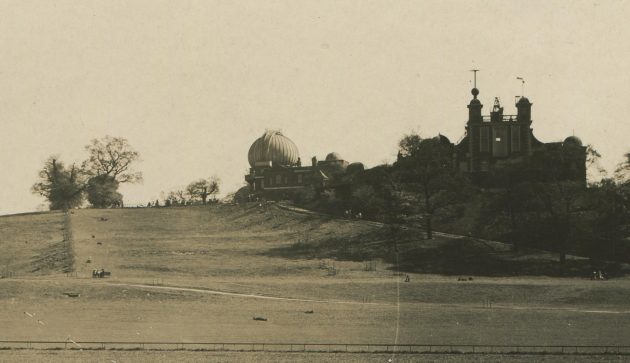

The Great Equatorial Building was built on part of the land enclosed in 1813. Its position is marked on both of the maps below. Note how the Observatory boundary hugs the outer edge of the avenue. Also note the four replacement trees towards the centre of the photo and the pile of horse droppings (bottom right). From an albumen print made in about 1903/4

The north-east corner of the courtyard where the tree now stands, consists of made-up ground, 124 loads of gravel having been recorded by Maskelyne in his journal as having been brought in from Blackheath. Since there was roughly level access into and from the courtyard, it seems likely that some amount of infill was also necessary outside the boundary in the Park, something that was confirmed in April 2022 during a ground survey when a localised thickness of at least 1.75 m of made ground was encountered in a borehole near the top of the Ascent on the western side (See Civil engineering stage 4 report p06-part-1).

Whilst the creation of the Courtyard brought the eastern boundary of the Observatory closer to the Grand Ascent, the enclosure of the Drying Ground brought it right up against the top of the steps. Both alterations, and particularly the second, must have had an impact on the topography outside, not least because following the second extension, anyone entering the courtyard from the south would have had to cross the corner of the Grand Ascent to reach it. In the adjacent plan, the positions of the trees on the west side of the Ascent (single row) and Blackheath Avenue (double row) have been marked as grey circles of varying sizes. As can be seen, four? of the pines originally planted at the top of the Ascent are missing, presumably having been removed to allow better access to the Courtyard.

The Ministry of Works file Work16/464 contains information about the gas mains passing though the Park to the Observatory from the 1849 when the first main was being planned up until 1959. In 1850, gas pipes were laid to connect the Observatory to the Phoenix Works (in Thames Street?). Although the proposed route was via the George Street gate on Crooms Hill and up the path that still exists today on the west side of the Ascent (1850 Report), it is not clear if this was the actual route followed. This is because in 1891, a request was made to 'open up a trench through the park form Park Row Gates to Royal Obsy, for the purpose of removing a defective main and to lay a new one in a similar position'. When this work was eventually carried out in 1894 an electric cable in a 1½-inch pipe was also placed in the trench. Its purpose however is unknown as the Observatory generated its own electricity from 1894/5 until 1912/13. When in 1909, the gas main needed upgrading from a three-inch to a four-inch one, the plan was to follow the route of the earlier 3-inch main which followed the pedestrian path down from the Observatory before turning off northwards and exiting the Park though the Park Row gate along a route that does not appear to have crossed the Ascent at any point. For reasons not explained, the pipe was routed instead straight down the western side of the Ascent (close to the hawthorns, and on an alignment parallel to and between the inner and outer rows of trees on the western side of Blackheath Avenue), before crossing the Parterre on its way to the Park Row gates. A memorandum dated 8 June 1909 states that the trench was to have a maximum width of two feet and a depth of two and a half feet.

The top of the Ascent also slightly disturbed in 1852 when galvanic wires were laid. Airy described their routing as follows in his 1852 Report:

'four insulated wires are laid in the ground, at depths varying from three to five feet, on a line commencing at the ground-floor of the North Dome (now called the Galvanic Room), across the Front Court, along the centers of the great avenues of the Park to the southern gate in the western wall of the Park, and by the south-east side of the road leading thence across Blackheath to the Lewisham Station; from which point two wires are carried, sometimes on poles and sometimes in grooved boards, to the London-bridge Terminus, where the connections will be made, either with the long Dover wires communicating with the Continent, or with the wires which extend to the Central Telegraph Station.'

The route is shown marked on a copy of the 1850 Sayer Plan (RGO6/610) and shows the route of the cables clipping the top of the ascent before proceeding up the centre of Blackheath Avenue.

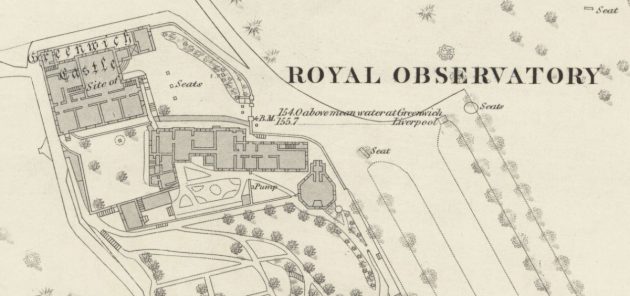

Map showing the top of the Ascent as it existed in 1867. Although the east side of the top of the Ascent is still in its original location, the top of the west side has had a large chunk cut out of it. Detail from the 1:2500 Ordnance Survey map: London - Middlesex & Kent XII.22 (surveyed: 1867, published: 1871). Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a (CC-BY) license

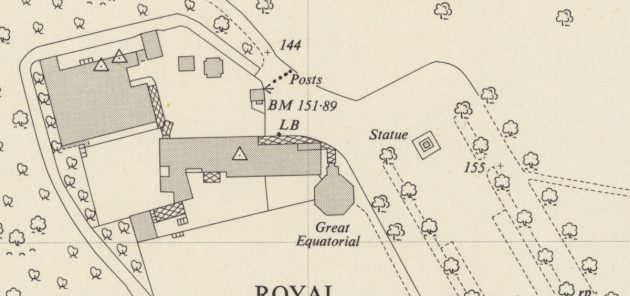

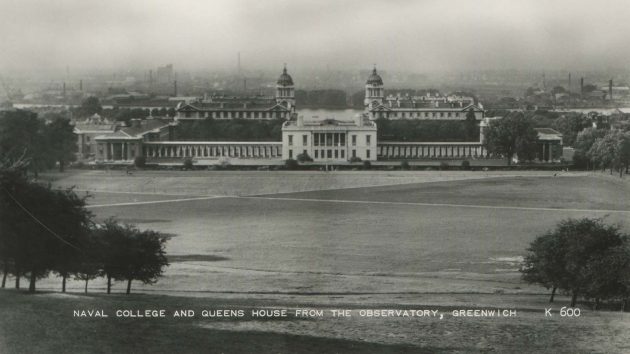

By the time the survey for this map took place, the Wolfe Statue had been erected and the Avenue extended northwards onto ground formally occupied by the steps. Detail from the 1:1250 Ordnance Survey map TQ3877SE – A (surveyed: 1950, published: 1951). Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a (CC-BY) license

This 1947 aerial view used by the Ordnance Survey to assist in the production of the map above. Detail from Ordnance Survey Air Photo Mosaic Sheet (1:1,250 scale): 51/3877 S.E. / TQ 3877 S.E. Prepared from Air Photos taken: May, 1947. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a (CC-BY) license

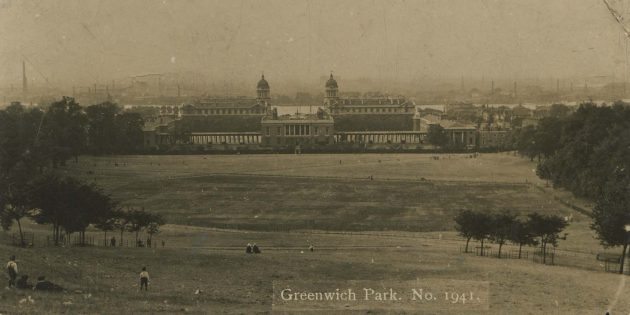

Looking down the Ascent towards the Queen's House in the late 1940s. During the war and for a while afterwards, a large part of the Parterre was used as allotments. They were still there when this picture was taken. From a postcard published by F. Frith & Co., Ltd

In 1979, work began on re-landscaping the area around the Wolfe Statue to the form shown here. The important thing to note, is that the hard-landscaping did not extend as far northwards as before, its northern edge having been moved back towards the Statue. It consisted of a low stone wall in front of which there was a row of Berberis (which developed into a hedge) in front of which was a low fence. Detail from a postcard showing the 28p stamp issued by the Post Office on 26 June 1984 to celebrate the centenary of the International Meridian Conference that lead to the adoption of the Greenwich Meridian as the Prime Meridian of the world. © Post Office

The same hard-landscaping as in the image above on 23 February 2021. In the 1980s, neither the black railings (left) nor the stainless steel railings (inserted in the stone-work) were present. The date when the Berberis and low fence in front of the wall were removed has yet to be established but is thought to have be when the stainless steel railings were installed and to have been around the time of the millennium. The black fence (left) was erected in 2008 (see below). The whole of the hard- landscaping around the Wolfe Statue was removed at the end of 2023 and reconfigured as part of Greenwich Park Revealed. This involved pushing the boundary forward again to the position shown on the 1950/1951 map i.e. to roughly the edge of the grassless area on the right – some twelve to thirteen metres forward of the 1670s position

Before concluding this section, it is worth recording that when the New Physical Building was erected, its east and west wings broke though the boundary by a few inches, whilst the southern wing went right up to it. This was both detrimental to the appearance of the building and inconvenient in terms of access to the outside spaces. Quite how or why the building came to be positioned so that it protruded marginally beyond the Observatory’s boundaries is unclear. To resolve the situation, it was put to the Treasury Solicitors that ‘In a matter like this which affects two departments of the Government and involves only a slight encroachment’ that the contract for the building works should be allowed to proceed. The Treasury Solicitors subsequently wrote to the First Commissioner of Works (in whose jurisdiction the Park fell) on 17 December 1897, authorising him to settle a new line for the boundary with the Admiralty (WORK16/139). Various options were considered to solve the problem of the eastern side of the building which included the whole of the Observatory's eastern boundary adjacent to Blackheath Avenue further into the park. A marked-up plan shows three alignments at these distances from the fence:

- 2.5 feet – by the First Commissioner

- 7.5 feet – proposed by the Superintendent (presumably Webster)

- 12.5 feet – proposed by the Secretary (

The first of these would have pushed the boundary right up to the outer row of trees in the Avenue. The second would have placed the outer row of trees just within the observatory's boundary. The third would have placed it in the middle of the path that now exists between the inner and outer rows of trees. Fortunately, none of the above were adopted. Instead, the boundary was made to do a wiggle around the edge of the protruding wing.

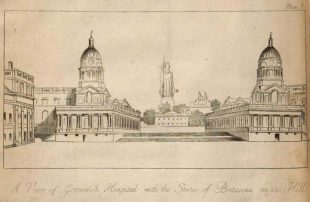

Flaxman's visualisation of his statue of Britannia at the top of the Grand Ascent which was included in his letter. Digitsed by Google from the copy in the British Library

Closing the view

The Wolfe statue has stood guard outside the Observatory and closed the view at the top of the Ascent since 1930. The gift of the Canadian people to the people of Britain, it was sculpted by Robert Tait McKenzie and unveiled on Thursday 5 June by the Marquis de Montcalm a descendant of Louis-Joseph de Montcalm whom Wolfe had fought at the Battle of Quebec. Wolfe, whose parents lived in Macartney House on the western edge of Greenwich Park, died in the battle as did Montcalm. After the battle, Wolfe’s body was repatriated and is buried nearby in St Alfege Church. The north side of the plinth on which it stands suffered shrapnel damage during the Second Word War, which remains visible today. Click here to read about the unveiling of the statue.

The Wolfe statue was not however the first statue proposed for the site. Back in 1799, John Flaxman in A letter to the committee for raising the naval pillar, or monument, under the patronage of His Royal Highness the Duke of Clarence proposed the erection of an enormous statue of Britannia. Click here for a more detailed view of the proposed statue. Flaxman's proposal came to nothing, as did a proposal a few years later to erect a pillar on nearby One-tree Hill to commemorate the naval heroes and victories of the French Wars

Erosion, picnics and the ever-shifting paths and fences – a chronological selection of pictures of the Grand Ascent from 1840–2023

The Francis Place etching from the 1670s at the top of the page (Facies Speculae Septen) shows three routes up the hill. A gently climbing path on a similar alignment to the present path, an angled path that hits the Grand Ascent about half way up before continuing steeply upwards along its western edge and a little used path up the centre of the Ascent itself.

The Griffier paintings show a well worn path rising steeply up the hill on the western side of the Ascent. None of the early plans of the Park show the location of any paths. The first plan so far identified that shows them is the Sayer Plan of 1840, which was republished at a reduced scale in 1850 (RGO6/610). At that time, the path running immediately below bottom step did not exist. What did exist however were two paths crossing the Parterre which crossed over each other just below the site of the bottom step. The first came from the vicinity of St Mary's Gate and crossed the banks of the Parterre twice, the second crossing being on the south bank (the section crossing the Parterre was removed in 2024). The second came directly from the Park Row gate and crossed the Parterre banks in no less than four place before rising up the centre of the Grand Ascent. The same path is also shown on the following Ordnance Survey map, but here it rises up the hill on the eastern side of the steps.

but not on this later one:

Ordnance Survey: London - Middlesex & Kent XII.22, Surveyed: 1867, Published: 1871

In this etching, which was published in 1840, a well worn path can be seen on the east side of the ascent (right). London from Greenwich Park, engraved by T. A. Prior and published by J & W Robins. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum Number: 1944,0704.12

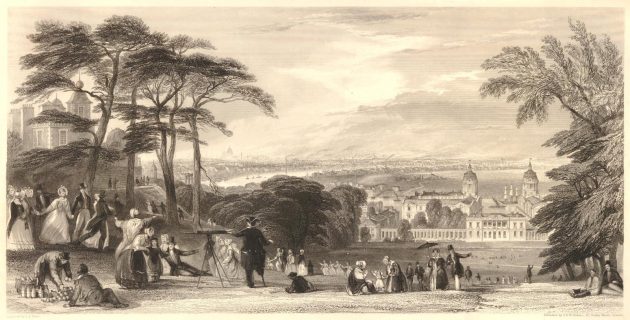

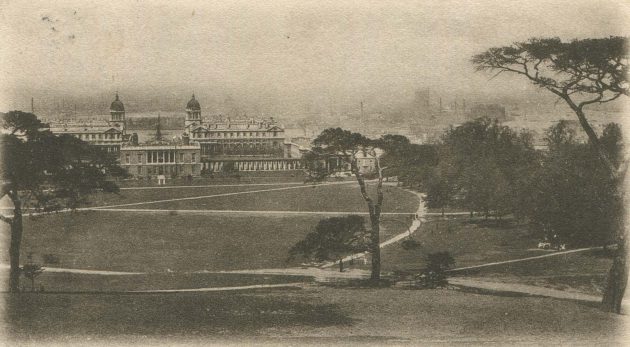

This watercolour by William Collingwood (signed and dated 1840) was painted from closer to the middle of the Ascent from where the view of London was less good. The path leading from Park Row to the bottom of the Ascent can be seen behind the trees on the right. Greenwich Hospital from the Observatory. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Accession Number P.9-1928 (see below)

As well as the Scots Pines obstructing the view of London from the top of the Ascent as they matured, the trees also blocked the view looking up to the Observatory from the north-east. Images looking across the Ascent towards the Observatory are thin on the ground from around 1750 until 1850. So too are images of Flamsteed House from the north that include the Grand Ascent. Things changed with the advent of photography and in particular stereo-photography. For a stereo-view to produce a good 3-D image, it needs objects in the foreground, objects in the in the distance and ideally objects in between. The two rows of trees with the Observatory behind were ideal – even if a large part of the Observatory was obscured!

The Royal Collection has a copy of the earliest known photograph showing the Grand Ascent.

Royal Collection Trust: 1893 photograph copy after an 1853 original (RCIN 2906076)

A large gap in the western treeline can be seen as well as a large amount of erosion on the slope. Of particular interest is the series of what look like railway sleepers on the eastern side (left). Nine can be made out and there were no-doubt others further up the slope. Their purpose is unclear but they could have used in an attempt to prevent further erosion of this part of the slope by stopping people from walking here. To the right of the bottom tree on the left, two paths are visible crossing the northern bank of the Parterre. The one heading off on a slight diagonal towards the bottom right hand is the path that was removed in 2024. The other, leading towards the photographer, is the path that ran directly towards this point from the Park Row gate (as shown on the Sayer plans). Also visible bottom right are some of the Scots Pines that were planted on either side of the terrace located between the bottom of the Ascent and the south end of the Parterre.

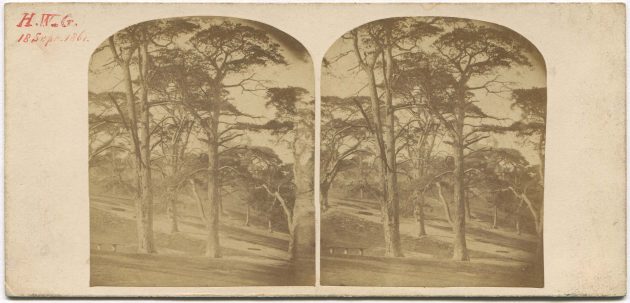

Carrying the date of 18 September 1861 and the initials HWG on the front, two of the 'sleepers' can be seen in this stereoview. It is not known if HWG was the photographer, the owner or both. Nor is it known if the card was published commercially. Flamsteed House is visible behind the trees (centre-right)

1857 Oil paining by George William Mote, Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial licence courtesy of The Cooper Gallery (Reference Number CP/TR 299) and Art UK (Reference: 68902) see below

A later view from 1869 painted from further down the slope. Note the couple with their picnic table (bottom right as well as the couple who appear to be sitting on one of the steps. London from Greenwich Hill by Henry Dawson. Oil on canvas, 1869. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, Accession number: B1981.25.216. Public Domain

Although the 1867/1871 OS map shows the path leading from the Park Row gate to the bottom of the Giant Steps as having been extinguished, the painting immediately below and early postcards show that the section crossing the Parterre banks was still in existence in the 1890s before finally being extinguished around the turn of the century.

The path rising up the eastern side of the ascent is clearly visible in this illustration which is thought to date from 1879. Observatoire de Greenwich pres Londres by an unidentified artist. Mixed media on paper

In this photo from the 1890s, the path coming from Park Row can be clearly seen. However, rather than ascend the hill, it appears to terminate near the tree in the centre of the picture. its onward path being blocked by a short section of fence. Note too the presence of a new path running along the bottom of the ascent (not shown on the 1:1056 Ordnance Survey map which was revised in 1893 and published in 1895 (link below). Detail from a postcard by Perkins, Son and Venimore

Ordnance Survey: London - London XII.22. Revised: 1893, Published: 1895

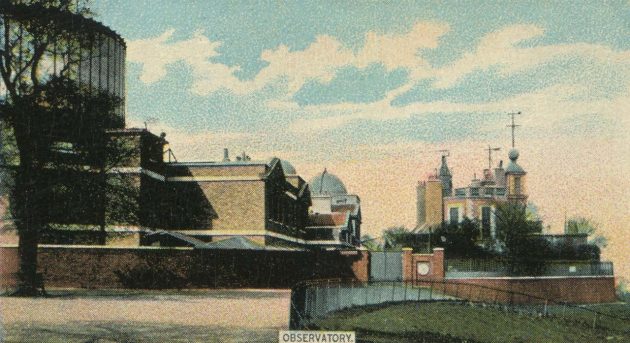

This view, which dates from around 1890, shows the second fence to be erected at the top of the Ascent. It remained in place until just before the erection of the Wolfe Statue in 1930. From a multi-view postcard published by the Chaucer Postcard Publishing Company

In this view from about 1904, the short section of fence at the bottom of the Ascent has been removed and the path from Park Row finally extinguished (though its ghost-like former presence can still be seen). The pines have also been felled and the new trees planted. Note the group of deer (bottom left). From a postcard published anonymously

Thought to have been taken two years later in 1906, this shot shows some people are enjoying the view, whilst others are intrigued by the photographer. It also captures phase one of Greenwich Power Station (top right) that had just been completed. From a postcard by Perkins & Son

Looking back across the Ascent towards the Observatory at around the same date (1906). From a postcard published anonymously

A second view of the fence at the top of the Ascent, this time from around 1911–15. From a postcard by S. Phillips, Catford

Taken by Phillips around the same time as the photo above (1911–15), this shot looks back across the Ascent towards the Observatory. Phillips was a prolific postcard publisher. Unlike most other publishers he didn't make duplicate negatives to print from. By the time this postcard was printed, the negative showed considerable signs of damage. From a postcard by S. Phillips, Catford

Thought to have been taken in the 1920s, the hillside shows no signs of erosion in this shot. Detail from a postcard published by C. Degen, London

By the time this photo was taken in 1925–27, part of the railings had been removed and a new path down the Ascent was beginning to form. From a postcard attributed to C.W. Green, Plumstead

By the mid 1920s, a bare patch had started to open up towards the bottom of the slope. The photo is thought to have been taken between 1925 and 1928. Detail from a postcard by Card House

To make room for the Wolfe Statue the area in front of the Observatory gates was enlarged by moving the fence at the top of the Ascent northwards. Rather than re-erect the old fence, which would have partially obscured the statue's plinth from the bottom of the hill, a new much lower fence, (similar to those that existed on the edges of the paths crossing the Parterre in the image above), was erected instead. It is thought to have remained in place until at least the 1970s. This image is thought to date from 1929–30 and comes from a postcard attributed to C.W. Green, Plumstead

Looking up the Steps in 1938. Note the scaffolding on the Great Equatorial Building that had been erected to allow the dome to be painted. Photographic print by an unrecorded photographer

Probably taken in 1950, this photo was entered by Valentine in their card register on 13 February 1951. The allotments have gone and there is no obvious signs of erosion on the slope. Detail from a postcard by Valentine & Sons Ltd.

A few years later, a new well worn path has become established. The image is thought to date from about 1955. Detail from a postcard published by Wilson College

By around 1958 when this shot is believed to have been taken, a deep rut had opened up in the middle of the path. Although remedial work was later undertaken, some sort of path continued to exist on the slope until at least the start of the 1970s. Detail from a postcard published by Gordon Fraser. Photo by by H. Luckyn-Williams

The Ascent on 21 July 1975. At this point there was no fence at the bottom of the Ascent and only the very low fence at the top. Photo © Peter Shimmon. Reproduced under the terms of a CC-BY-SA 2.0 license (see below)

By the time this photograph was taken on 28 October 1981, a fence had been erected across the bottom of the Ascent. Note the manhole cover (bottom left), which is believed to be related to a soak-away system that is thought to have been installed in the 1960s or 70s. It was covered over in 2024. The grass where the earlier path had been looks greener than that on either side. Photo © David Dixon. Reproduced under a CC-BY-SA 2.0 license (see below)

In this shot taken in May 1994, the fence at the top of the Ascent can be seen as well as the fence at the bottom. Immediately in front of the top fence is the Berberis hedge. Although determined people were still able to find a way onto the grass, there is little sign of erosion. © Gordon Beach. Reproduced under a CC-BY-SA 2.0 license (see below)

In this later view taken on 18 October 1998, the grass shows bare patches, but the Ascent is still free of a path to the top. © Nick Macneill. Reproduced under a CC-BY-SA 2.0 license (see below)

The unofficial path that existed on the hillside just to the east of the Grand Ascent. It started where the fence at the bottom of the ascent came to an end. In order to try and stop people from using it, in 2008 a new and extended fence was erected at the bottom and the fence at the top extended. Unlike the old fence, the new one was rather easier to climb over. Photo: 22 May 2007

Looking down the Ascent at sunrise on 4 February 2009. Note the straw bails that have been placed in front of the fence to protect tobogganists from injury. Note also the ridging on the slope that the previous days sledging had revealed. It is likely to have been caused by small scale slumping in the upper layers over a long period of time

By the time this photo was taken on 16 June 2010, a new path down the centre of the Ascent had become established and the new fence damaged by people climbing over it. © Robert Lamb. Reproduced under a CC-BY-SA 2.0 license (see below)

By the time this photo was taken just a few weeks later on 22 July 2010, the damaged section of fence at the bottom of the Ascent had been removed

By the time this photo was taken on 30 April 2011, a new fence had been erected with vertical rather than horizontal rails. In an attempt to stop people walking and sitting on the Ascent several temporary barriers were also erected at various points across the width of the Ascent

When this photo was taken on 22 May 2012, the stadium for the equestrian events for the 2012 Olympic Games was under construction. Given the global TV audience and the fact that aerial shots would include the Ascent and the Observatory, an attempt was made to eliminate the path up the Ascent by erecting numerous short lengths of fencing (chestnut paling) across it. Although they are difficult to count here, satellite images on Google Earth suggest that nine lengths were erected in total

Taken during the games on 4 August, this picture shows that the chestnut paling had done its job and allowed the bare area where the path was to have been successfully reseeded. The tower behind the Wolfe statue supported three wires carrying the traveling camera which was used to film above the stadium

By the summer of 2013, the path down the centre of the Ascent had become re-established. This photo captures it on 30 June 2015