…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

The ice house adjacent to the Observatory in Greenwich Park

The purpose of this page is to bring together details from all the known historic records, many of which have previously be known only to a tiny handful of people and some of which have never before appeared in print.

Introduction

The early 1600s were an important period in the development of Greenwich Park. The building of the Queen's House commenced in 1617 and in 1619, work began to replace the two-mile long wooden fence surrounding the Park with a high brick wall. At about the same time, it seems that two snow wells (which were also referred to as snow conserves or conserves for snow) were constructed. Contemporary records record their construction, but not their location within the Park.

Greenwich Park in the 1630s about 15 years after the two snow wells were constructed. Greenwich Castle (later the site of the Royal Observatory) is on the left. The Queen's house (completed 1635) is in the centre along with the Tudor Palace and the River Thames. Wenceslaus Hollar's 'long view of Greenwich' (1637). � The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1850,0223.254 (see below)

What is known for certain is that an ice house existed close to where the Observatory was constructed in 1675/6. Its presence and location is recorded in several of the Observatory's records including:

- One of the engravings of the Observatory made by Francis Place in about 1677 soon after the Observatory was founded

- Published and unpublished site plans drawn by the Astronomer Royal George Airy in the mid-nineteenth century

- Correspondence between Airy and the Chief Commissioner of Parks in 1860

- Admiralty plans of the Observatory published between 1885 and 1911

But was this ice house one of the two ice wells? The limited evidence available suggests it was and that the original well was significantly modified in the 1660s when the Park was transformed from one used for hunting to the landscaped park that we see today.

The Exchequer Pipe Office declared accounts from the 1620s

The History of the King's Works, vol 4 pt.2 (1982) covers the period 1485-1660 and states the following much referenced paragraph at the end of the section on Greenwich:

'Also in the Park was a snow conserve. Built in 1619–1620, this consisted of a bricked-out well 30 feet deep and 16 feet across, with a thatched timber house with a door. The thatchers also provided 'waddes', presumably for insulation[1]. A second,smaller, conserve was dug in 1621–2[2]. One of these conserves had its 'bottome floore' and 'uppermoste floore' new made in 1625–6[3]. This suggests a bottom floor raised over a sump and an upper floor to carry the wads (presumably of straw) which would have to be lifted whenever the conserve was used'

1. E351/3253 (task-work: John Payne and Thomas Tokens, bricklayers and 'diverse persons' thatching)

2. E351/3255 (task-work: John Bartholomew and others)

3. E351/3259 (prelims.)

The three references that the authors give are to the Exchequer Pipe Office declared accounts at the National Archives. Transcripts of the relevant sections are given below.

The transcripts

Each set of pipe accounts consists of numerous sheets of parchment written on both sides and stitched together along the top edge. Each covers the expenses of all the King's estates and is organised alphabetically by location. Each location typically begins with an introductory paragraph summarising the work carried out during the accounting period followed by a list of expenses followed by wages paid followed by a list of payments made for task-work. At this point, all the transcripts should be regarded as provisional.

E351/3253 (1 Oct 1619–30 Sep 1620)

The introductory paragraph mentions more than one well in the Park, but it also refers to 'the well'. Although it doesn't specifically mention the 'snow well' or 'snow conserve', it seems probable that this is what may sometimes be being referred to when the wells are mentioned. For the sake of clarity, the whole of the introductory paragraph is transcribed below:

'Also allowed to the said Accomptante for money by him paid for sundry workes buildings and reparations donne and performed in and upon the mannor house of Greenewiche with the Tower in the parke; viz repayring the wharfe where it was decaied, frameing twoe curbes for welles in the parke with a roofe, a dore and dorecase to one of them, mendinge and sodering of broken pipes and of the leades and gutters fynishing the rayles at the wharfe, setting upp proppes and shores to defende the staires by the ballaste wharfe laying a floore at the bottome of the well in the parke with a roofe for the same, setting up postes and railes and paleing the same, fixing [?] out of Rafteres over the kings greate chamber, newe tyleing sundry rooms, squareing and setting hard stone steppes in the kings privy garden, making cleane the white marble fountayne making sundry doores and pticons [partitions?], taking downe the twoe Phesannte houses, making of tables tressles and forms, adzing Dressers in the Larder and kitchens, mending with plaster of Paris the walles of the Tennis courte and blackinge them all over, mending the walles rounde aboute the conduit courte and the courte by the hall, couloring the same russett, whiting and couloring all the walles aboute the hall, making a cornish aboute the Lobby in the garden fittinge and setting upp tables for St Georges feaste, newe matting[?] and mending sundry rooms, taking downe the toping of a wall upon the leades by the Marques of Buckinghams lodgings and setting it upp againe, joysting and boording a floore Lxty [60] foote longe and xii foote broade for the saide Marques, settinge upp foure [?] Dormer windows there, weinscotting a room Lxty foote longe for the same Marques, mending the tower and lodge in the parke wth sundry of the woorkes donne there as in the severall paybooks of that house are conteyned The pticularities of all with charges are hereafter sett downe as followeth. Viz'

The key sections relating to the wells are:

'... frameing twoe curbes for welles in the parke with a roofe, a dore and dorecase to one of them ... laying a floore at the bottome of the well in the parke with a roofe for the same, setting up postes and railes and paleing the same ...'

This seems to imply that two wells were dug, though only one of them appears to have been for snow. It was presumably this one that had a floor installed at the bottom together with roof and walls walls which sound as though they were constructed in the same way as a fence. Typically made from wood, a curb is a circular structure rather like the rim of a wheel that was used during the construction of a well. Whether these particular ones were used singly in two wells or together in one is not known. Nor is it known if one or both were used in constructing the snow well. Typical practice when digging a well was to start by excavating a circular hole to a depth where the sides started to cave in. The curb was them placed in the hole and layers of brick placed on top to just above ground level. The well would then be excavated a small amount further, starting from the centre of the well and gradually working towards the edge and finally be removing material from beneath the curb which would eventually sink down under its own weight. More courses of brick would then be added on top and the process repeated until the required depth was obtained.

From the section on expenses:

'Ladders viz one of xxty rounds vs, and one longe ladder to stande in the well xxs in all ... xxvs [25s]'

It is not stated which of the wells the long ladder was intended for (was it both?). Nor is it stated if it was intended for use during the construction stage or as a permanent fixture to give access (or both?).

Consecutive entries from the section on task work:

'John Payne and Thomas Tokens bricklayers for bringing upp with brickes the well in the parke to preserve snowe beinge xxx foote deepe and xvi foote over the some [sum] of … cs [100s i.e. £5]

Diverse persons for thatching the well and for waddes for it xiiiis fillinge upp the wharfe where the newe stones were made by the ballast wharfe vis viiid and for pavinge with ragstone under the arche by the waterside xx yeards at iiid the yearde vs in all the some of …. xxvs viiid'

Although the accounts make reference to the work of the bricklayers, it is not clear if they were working in a pre-dug hole or were sinking a well using a curb. The reference to 'waddes' (presumably bundles of straw or similar) suggest that the well that was thatched was the snow well. The wads were presumably to lay on the snow to insulate it. If the walls were made of wood as indicated in the introductory paragraph, they were probably thatched or covered in wads too.

E351/3255 (1 Oct 1621–30 Sep 1622)

'Taskewoorkes viz to Thomas Barwood Pavior for pavinge twoe dores at the end of the hall conteyninge xxii yards at iii d the yard st [sub-total?] vs vid. John Bartholmewe and other Laborers for digging and sinckinge of a well for a conserve for snowe in the parke beinge xiiiien [14] foote over and xxx [30] foote deepe st ix£ xs. And to Peter Wilkins and others for clensinge the common vaulte belonging to the upper stables by agreement st xLs. In all the some of …. xi £ xv s vi d'

E351/3259 (1 Oct 1625–30 Sep 1626)

There is only a brief mention of the snow well in this set of accounts. The transcript below comes from the introductory paragraph:

'... newe makeing of the bottome floore of the conserve for snowe in the Parke, and new makeing the uppermost floore there the olde being all rotten...’

The cost of the wells

The structure and lack of detail of the financial accounts makes it impossible to work out the true cost of constructing the snow wells. No figures are given for the cost of the buildings that covered them, apart from the cost of thatching the first one. Nor do we know how many bricks were used. However, we do have an idea of how much they cost. The first set of accounts gives two figures (presumably because they were for bricks of a different quality or size). They were 11s 6d and 12s per thousand. The second set gives just one figure which was 12s per thousand. We also know the daily rate paid to bricklayers. Four different rates are given in the first set of accounts. which also include the daily rates for labourers. Given that the entries relating to the 'digging' of the wells are listed under task work, the charge presumably includes all the associated labour costs for that part of the build. We do not know the cost of the curbs (if indeed they were used). Nor is it clear if the full cost of the 'longe ladder' should be assigned to the first snow well. The accounts also refer to the supply of wheelbarrows, shovels and spades for use at Greenwich. Perhaps a portion of these costs should be included too.

The correctness of otherwise of the accounts by the authors of The History of the King's Works

It is quite clear from the transcripts that the authors of the The History have put their own interpretation on the limited amount of information the accounts provide. They may well be right; but they have made a number of assumptions about which bits of the accounts apply to the snow wells and which bits apply to other wells within the Park.

Whether it was their intention or not, their writings could easily be taken as meaning that the second well had a similar form to the first. Maybe it did, but equally, maybe it didn't. It is also misleading to state that it was smaller than the first snow well without any qualification as most readers might well think that it was rather smaller than the accounts suggest.

Whether the authors were correct in with what they understood by the 'bottome' and 'uppermost' floors (E351/3259) is another matter. An alternative interpretation is that the bottom floor was at the very bottom and probably made of stone or brick with a hole in the centre that allowed the melt water to drain away, and that the uppermost floor was a wooden grill that sat a few feet above it on which the snow rested.

The geology of the Park and the shape of the well

Ice houses come in many shapes and sizes. Although the records tell us the depth and the width of the ones constructed at Greenwich in the 1620s and that at least one of them was definitely lined with brick, they don't tell us anything about their profile. Nor do they tell us exactly what and wasn't included in the depth measurement or if the width (presumably measured at the top) was the internal diameter or the external diameter of any brickwork.

The bench mark on the brick pier by the courtyard gate in about 1870. Cut into the brickwork, it consisted of a horizontal line with a vertical arrow head beneath it

In 1914/15, a bore hole was sunk just a few yards from the ice house to establish the underlying geology and the results reported to the Observatory's Board of Visitors by Frank Dyson. the Astronomer Royal, in his 1915 Report:

'In view of the success which has attended the underground meridian marks at the Cape Observatory, borings were made just outside the S. collimator of the Transit Circle and at the end of the Astronomer Royal's garden [presumably on the meridian]. The first of these was stopped at a depth of 37 feet after passing through 29 feet of very hard compact ballast. Throughout the last 24 feet it was necessary to use chisels almost continuously before the core could be removed with an augur. It was considered that this formation was very suitable for the construction of a collimator pit of relatively shallow depth. The boring in the garden, which is about 40 feet below the level of the ground near the transit circle, indicated an entirely different formation. The bore was sunk to a depth of 58 feet in 8 days, the last 42 feet being in very fine dry sand. In consultation with the Civil Engineer the conclusion was reached that it was useless to proceed further, as absolute stability of a mark could not be anticipated, especially as a well shaft would form a channel by which surface water could reach and probably disturb the sand.'

The implication of this is that the whole of the lower half of the shaft of the ice house would have been located in the sand layer and this could have had major implications for the way it was constructed. The fact that the bottom of the ice house was made of sand, would have meant no pipework was necessary to drain away the water produced as the ice melted.

According to Susan Roaf in the Book The Ice-houses of Britain which she co-authored with Sylvia Beamon, 'the first ice-houses in Britain in the seventeenth century were brick lined, inverted cone-shaped wells covered with roofs of timber and thatch.' There is nothing in the book to support the statement about them being cone-shaped; but there is a 1665 quote from John Evelyn about Italian ice houses being 'excavated in a conical form' which was 'made flat at the bottom or point' which she seems to have conflated with what he said about the Greenwich ice house (see below). Nor is there anything in the book's 500 plus pages about how a cone or other shaped structure might actually have been constructed or how earlier builders might have coped with unstable soils.

The financial accounts are too vague for us to know exactly how the snow wells were dug. We know from the 1619–1620 accounts that two curbs were constructed, but were they both just a few feet across or was one of both of them around 16 feet across and used in the construction of the snow well? We just don't know. The 1621–1622 accounts fail to mention what the second snow well was lined with. They do however use the words 'digging and sinckinge' the snow well... so does that mean that a curb was used? Again, we just don't know. If the snow well was built using a curb, it may have been reinforced with spokes and the well would presumably have had vertical sides.

If no curb was used, then based on what Dyson said about the compacted ballast layer, it would have been impossible to bang posts into the ground to support the sides of a hole while the well was being dug through this layer. Once the sand layer had been reached, it would presumably have then been possible to shore up the sides of the ballast layer by banging posts into the sand layer. In the absence of any further shoring within the sand layer, the snow well is likely to have had sloping sides in the lower half

If neither a curb nor any shoring was used, the initial hole would have had to be considerably wider than the diameter of the well itself and back-filled as the brickwork was constructed. In this case an initial hole perhaps as much as 100 feet across may have been required. A smaller hole however would have been needed if it was less deep and the required depth of the well achieved by using some of the excavated material to build up the ground level around the top of the well – something that may have been easy to achieve given that the ice well was built on the side of a hill.

Published contemporary descriptions of how wells were dug are scarce to non existent. The two articles below help provide some degree of insight:

Descriptions of the King's wells. Philosophical transactions (1783)

Repairs in 1637?

In the book Faeriecraft which was first published in 2005, Alicen Geddes-Ward makes reference to a bill from1637 for repairing 'the' snow well. The source of this information was another author, Jack Gale, who has written two books that mention the snow well at Greenwich. The most recent is titled Magic for the next thousand years and was published in 2004. The second, Goddesses, Guardians and Groves was published in 1996. Whilst the structure he mentions is clearly not one of the snow wells, he may well have come across a genuine reference to a 1637 repair. Possible sources for future research are the Pipe Office declared accounts.

The interregnum (1649–1660)

During the interregnum that followed the execution of Charles I, the Park fell into the hands of the Parliamentarians where it remained until the monarchy was restored in 1660. During this period, Greenwich Castle fell into disrepair as did the Tudor Palace at the bottom of the Park. It seems likely that the ice house may have suffered too, though there is no direct evidence one way or the other.

The financial accounts relating to the landscaping of the Park in the 1660s

King Charles II by John Michael Wright. Oil on canvas c.1660-1665. � National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence (see below)

‘At Woolwich, up and down to do the same business; and so back to Greenwich by water, and there while something is dressing for our dinner, Sir William [Penn] and I walked into the Park, where the King hath planted trees and made steps in the hill up to the Castle, which is very magnificent.’

Six months later, the Dutchman William Schellinks also noted the steps in his journal, recording in the entry for 25 October 1662:

‘On the hill in the park behind the [Queen’s] house two avenues of trees had been planted from the bottom to near the top of the hill, where it was too steep to climb up, steps had been cut into the ground to walk up in comfort.’

The steps that both Pepys and Schellinks referred to were a series of grass terraces or ‘ascents’ which later became know as the ‘Giant Steps’. Directly in line with the centre of the Queen's House, they formed part of a grand axis about which the park was to be transformed from a place used for hunting to a park and garden in the French style to rival those of France. Although no plans or other records of their work survive, it is suspected that the two Frenchmen, André and Gabriel Mollet were involved in the early stages of the Park's redesign as there is a warrant from August 1661 that refers to them as the 'designers of all his [the King's] gardens for altering them and making them into the neatest formes'

Andre Le N�tre (1613�1700). Bronze copy made in 1913 by Adrien-Aur�lien H�brard from the original marble bust by Antoine Coysevox on the tomb of Le N�tre in l'�glise Saint-Roch, Paris. Photographed October 2012 in the Jardin des Tuileries. Louvre inventory number: TU 108

The landscaping works began under the supervision of William Boreman, who not long after was replaced in this role by Adrian May who was also overseeing the landscaping of Hampton Court and St Jame's Park. Following May's death in April 1670, his financial accounts for the period 1663(?)–1670(?) were presented by his brother Hugh on his behalf. By this point, the transformation of the Park from hunting ground to the formal layout with its tree lined walks (avenues) and giant steps was largely complete.

The financial accounts of Sir William Boreman carry the following reference numbers and are important for reasons that should become clear later:

- SP29/56 (Secretaries of State: State papers domestic, Charles II. Letters and Papers)

- E351/3428 (Exchequer: Pipe Office: Declared accounts. Works and Buildings (Miscellaneous). Sir William Boreman. Works in Greenwich Park)

SP29/56/39&39.1 are single page documents. The first is a covering letter from Boreman that begins 'May it please yor Majesty'. The second is an unaudited breakdown of the money expended on the redevelopment of the Park between 1 September 1661 and 10 June 1662. The account is presented in three sections under the following headings:

- 14 Coppices

- 7 Walkes

- 12 Assents

E351/3428 is the Exchequer Pipe Office declared Account and contains Boreham's certified account for the same period. Not only is it more detailed, but the money is accounted for differently. Spellings are different too. Of much greater significance however is the fact that the stated number of Coppices and Walkes constructed has been changed. The number constructed as recorded in this document are:

- Coppices: 16

- Walkes: 4

- Ascents: number not specified

The change from 14 to 16 Coppices is important to know when examining the evidence that comes later, the number 16 being confirmed in another set of Boreman's accounts covering the period 1662–1665 (SP29/116/14).

There are two copies of May's financial accounts at the National Archives, which in theory should be identical. Their reference numbers are: E351/3431 and AO1/2481/292. As well as the accounts for Greenwich Park, they include the accounts for works carried out at St Jame's Park and Hampton Court, each park being dealt with in a separate section.

The Greenwich section makes reference to both Snow Hill Walk and the ice house, which is referred to in the document as the Snow Well. The construction of Snow Hill Walk (which can be seen in the Francis Place etching above) involved the movement of a considerable quantity of earth as the steep slope at the edge of the plateau on which the Observatory stood was transformed into one with a shallower and more even gradient.

The accounts are difficult to read. In part this is because of the abbreviations and spellings that were used along with a lack of punctuation. Another problem is the way numbers were written in Roman numerals which differed considerably from modern practice. Important abbreviations to note are p (per) and st (sub total). The accounts use an obscure unit of volume called a ffloore which David Jacques informs us is a rod square by one foot deep i.e a volume of 5.5 x 5.5 x 1 or 30.25 cubic feet (which is equivalent to 1.12 cubic yards or 0.857 cubic metres).

A transcript of the whole of the two paragraphs that refer to Snow Hill Walk and the snow well are given below. The text is taken from E351/3431. It is hoped to provide a transcript of the rest of the Greenwich part of the document elsewhere on the website at a later date:

'The Charge of makeing the Snowhill Walke viz To the said Edward Maybanke and Thomas Greene according to the severall Admeasurements thereof expressed in the said Acco’s [Accounts?] thereof at the rate of iis xd p [per] ffloore for iiii*C iiii [404] ffloores pcell [parcell?] there of st [sub-total] Lvii£ iiiis viiid, At the rate of iis vid p ffloore for Cxxxty [130] ffloores other parcell thereof st xvii£. And at the rate of iis p ffloore for Cxxty [120] Floores residue of the said Admeasurement of the said Walke st xii£. ffor Digging of CCCxLi Holes at iiid each st iiii£ vs iiid ffor xvii dayes and one half dayes worke at xviid p diem [day] st xxxviis viid [see note1 below] ffor makeing the slope on ye Hill by Agreement st Cs. ffor Cleering the Pond to gett Water for the Trees st vis viiid ffor makeing the Hols at the Steepe hill being xxxviien [17] Rodds and a halfe at iis viiid p Rodd st Cs ffor Worke donne at the Foote of the Snow Hill being xv ffloores at iiis p Floore st xLvs. In all ffor the Charge of the said Snowhill Walke as by the said Accompt and sundry Acquittances of the said Undertakers amongst other Payments Appeared Ciiii£ xixs iid

More paid to the said Edward Maybanke Robert Bearde and the rest of the Undertakers for carrying Earth that came off the Snow Well conteyneing by Admeasurement xLixne [49] Floores at iis vid p Floore st vi£ iis vid ffor vi mens Workes ii dayes st xviiis ffor the Hill beyond the Oake conteyneing xii ffloores at iis vid per ffloore st xxxs ffor Carrying Earth into the Levell beyond the Queenes Tree st xxiiii£ ffor filling the Upper Corner on the left hand st iiii£ xs ffor Covering the Snow Hill Walke with mould st iiii£ ffor Carrying Turffe st Ls ffor making the Levelle Line to the Circle [see note 2] st lxs ffor x ffloores of Earth to raise the lower part of the Angle Walke st xxxvs ffor digging of ixCLty [950?] Holes st (sub-total) viii£ ffor five ffloores at the Upper Returne at iiis vid per ffloore st xviis vid And for digging xxvi Holes at iiid per Hole st vis vid In all paid the said Undertakers for the said services as by sundry Acquittances of the said Undertakers amongst other Payments appeared Lvii£ ixs vid

[1] Either the scribe or Hugh May seems to have made an error here as the arithmetic does not work. It would if they had said 26.5 days at 17d per day. The figures in AO1/2481/292 are the same.

[2] The circle is presumably a reference to the point where Snow Hill Walk crossed another walk (avenue) at the bottom of the hill (see maps below)

So what were these 49 Floores (equivalent to 1,482 cubic feet or 42 cubic metres) of earth 'that came off the Snow Well'? One possible explanation is given in the next section.

John Evelyn's recollections of the ice house c. 1665

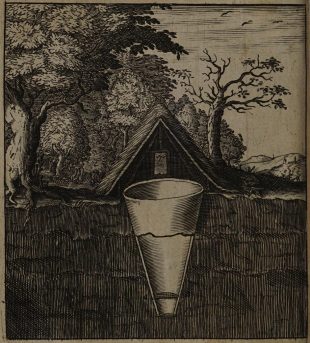

The illustration of an Italian snow pit that was placed opposite Evelyn's description. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection

'And therefore meeting the other day (by good chance) with my ingenious friend Mr. J. Evelyn, his inquisitive travels, and his insight into the more polite kinds of knowledge, and particularly Architecture, made me desire and expect of him that account of the Italian way of making conservatories of snow, that I had miss'd of, in several Authors; and having readily obtain'd my desire of him, I shall not injure so justly esteem'd a style as his, to deliver his description in any other words, then [than] those ensuing ones, wherein I received it from him.'

[‘]The snow Pits in Italy, &c. are sunk in the most solitary and cool'd places, commonly at the foot of some mountain or elevated ground, which may best protect them from the Meridional [midday] and Occidental Sun, 25. foot wide at the orifice, and about 50. in depth, is esteem’d a competent Proportion. And though this be excavated in a Conical form, yet it is made flat at the bottom or point. The sides of the Pit are so joyc'd, that boards may be nail'd up on them very closely joynted. (His Majesties at Greenwich newly made on the side of the Castle-hill, is, as I remember, steen'd [lined] with Brick, and hardly so wide at the mouth.) About a yard from the bottom is fix'd a strong Frame or Tresle, upon which lies a kind of woodden grate; the top or cover is double thatch'd, with Reed or Straw, upon a copped frame or roof, in one of the sides whereof is a narrow door-case, hipped on like the top of a Dormer, and thatch'd, and so it is complete.[’]

The important thing to note is that Evelyn (as reported by Boyle) said the snow well in the Park was 'newly made'. Exactly what he meant by 'newly' is a matter of conjecture. Did he mean in the last year or two, or did he mean 40 or so years before. The former seems the more likely. But did 'newly made' mean that a derelict snow well had been refurbished or did it mean that one had been created from scratch? Given the cost and the work involved (since both were brick lined), it seems most likely that Evelyn was talking about a refurbishment.

Based on later information that comes from Airy (see below), it seems highly probable, that in his time, the ice house had an earthed over brick dome that sat over the structure below and that it was entered via an access tunnel. Since such a tunnel is shown in the Francis Pace etching below, it would seem that the ice house had already had this form in 1677. But how might such a brick dome have been constructed? One possibility is that the well was filled with earth to make a former on which the brickwork was constructed and then removed once the job had been completed. It is worth noting, that the 1,482 cubic feet of earth 'that came off the Snow Well' (mentioned above) is equal to the volume of an inverted cone 14 feet wide at the top and 30 feet deep. Such a cone would store between 17 and 30 plus metric tons of compacted snow, depending on the degree of compaction.

The Francis Place etchings

The foundation stone of the Royal Observatory was laid on 10 August 1675 and in July 1676, the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, took up residence. About a year later, or perhaps the year after that, Robert Thacker, an employee of the Board of Ordnance, made a series of drawings of the Observatory and its instruments. Although the drawings are now thought lost, contemporary etchings made from them by Francis Place survive in small numbers. There are 12 in total. Of these, three are of interest in the context of the ice house. They are a plan of the Park (commonly known as the Pepys Plan), a view showing the Giant Steps (also known as the Grand Ascent), and a view from the roof of Flamsteed House that shows the entrance to the ice house and is reproduced immediately below.

Prospectus Australis. The thick vertical line near the centre is the mast used to support the 60-foot telescope. Part of the sloping area of ground to its left, beyond the boundary wall, is the area enclosed for the Observatory in two stages in 1814 and 1837. To the left of the mast, in the foreground, the Quadrant House can be seen and to the right, the Necessary House (toilet). Running from centre left to bottom right is an avenue of trees known today as The Avenue, but labelled on the Travers map of 1697 as Snow Hill Walk (TNA/MR1/253). The entrance to the ice-house can be seen a little above and to the left of the figure standing behind the mast. � The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.951 (see below)

Detail showing the entrance to the ice house (top centre). Note the alignment of the entrance tunnel. It is consistent with the later plans and faces down the hill towards the St Mary's Gate entrance to the Park. � The Trustees of the British Museum

Early plans of Greenwich Park

The five earliest plans of Greenwich Park

Date |

Name of

|

Ice houseshown |

Ice houselabelled |

Named

|

Labelled

|

Unlabelled

|

Archive

|

|

| c.1677 | Pepys | Yes | No | 0 | 0 | 3 | b | |

| 1693 | Gascoin | No | n/a | 7 | 5 | 0 | c | |

| 1697 | Travers | No | n/a | 7 | 5 | 0 | d | |

| early 1700s? | Woodlands | Yes | No | 0 | 1 | 3 (4?) | e | |

| early 1700s? | Wise | No | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 | f |

a: The conduits date back to Tudor times and were originally constructed to

supply water to Greenwich Palace and afterwards to Greenwich Hospital. The schedule to the

Travers plan names them

b: Etched by Francis Place after Robert Thacker.

Copies in Pepys Library Cambridge & Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust

c. National Archives (MR1/329)

d: National Archives (MR1/253) schedule (MPE1/245)

e. Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust

f: Royal Museums Greenwich (CMP/30; ART/6)

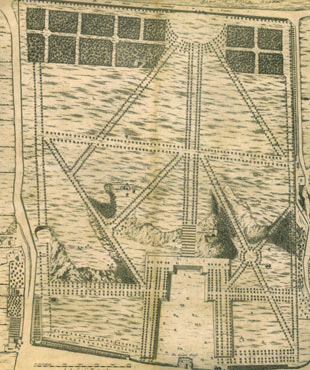

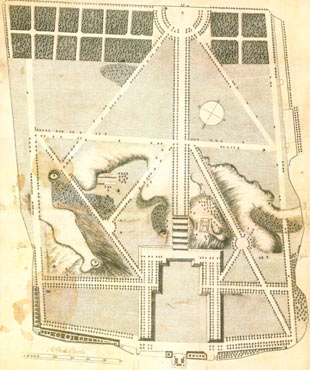

In each of the five plans below, south is at the top. All have been cropped – The Pepys and Woodlands Plans marginally so, the others rather more.

Detail showing Greenwich Park from an early nineteenth century copy of the Travers map of 1695. Snow Hill Walk (now known as The Avenue) can be seen running from top centre to bottom right. The ice house (not shown) was tucked into the hillside on its left. The Queen's House is marked with black hatchings (bottom centre). The Survey began his on 24 February 1695 and was completed on 27 May 1697. It was titled A survey of the Kings Lordship or Manor of East Greenwich in the County of Kent. Its purpose was to identify the King�s property and the encroachments thereupon. As such, many of the other buildings that existed at the time were omitted. This copy was redrawn and lithographed at a reduced size by J & J Neele and published in 1816 in John Kimbell's An account of the legacies, gifts, rents, fees &c. appertaining to the church and poor of the parish of St Alphege Greenwich, in the County of Kent, .... It contains errors and some labels, including Terrace Walk, have been omitted

Click here to read more about the original Travers map and the 1816 copies.

Of the five plans, only the Pepys and Woodlands plans show a structure in the location indicated as the site of the ice house on the nineteenth century Observatory plans. They both show it as a three-dimensional structure rather than in plan view and both show it as a rectangular building with a simple pitched roof, the ridge running roughly north-south and the long side being about twice the length of the shortest. The Pepys plan also shows a door on the short north facing side. The orientation of the structure on both plans is similar and crucially, is different to that shown on the later nineteenth century plans (see below). It is also at odds with the Francis Place etching at the top of the page. A possible explanation for this is that the Pepys plan is not all that it seems and that it has its origins in a now lost plan from the early 1660s.

The origins of the Pepys plan and discrepancies with the other Francis Place etchings

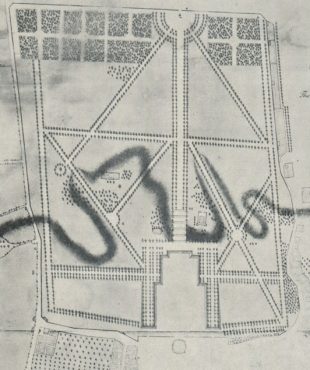

Annotated detail from the Pepys Plan showing Snow Hill Walk (S.H.W.), the Observatory (Obs.) and the Snow Well. The trees on the hillside around it are marked as 'the chestnut nurserys' on the Gascoin plan of 1693. � Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust

Detail from the Pepys Plan showing the conduit head in the north east corner of the park � Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust

There are three key differences between the Pepys Plan and the later Gascoin and Woodlands Plans that are relevant here. The first is in the number of steps which are shown. The second relates to the avenues of trees. The Pepys Plan shows all the avenues completely planted. The two later plans show lots of gaps in the avenues in the southern half of the park with the exception of the southern boundary, the main avenue from the Blackheath Gates and the 'rounds' which were adjacent to the gate (were these prioritised in order to impress visitors arriving from Blackheath?). The gaps elsewhere, whilst substantial are not identical on the two plans. The difference between them and the earlier Pepys Plan is difficult to explain. A previous theory that the losses were due to storm damage in 1703 is clearly incorrect. Other possible explanation that needs to be considered include felling for timber, premature death and a further scenario that is discussed below. The third difference is in the number of coppices shown at the south end of the Park.

As noted above, Boreman's declared accounts for the period 1 September 1661 to 10 June 1662 state that seven walkes were constructed. The declared accounts state there were four. Likewise, the unaudited accounts state that fourteen coppices were constructed whilst the declared accounts state there were sixteen. The number of sixteen is also appears in Boreman's second set of declared accounts (SP29/116/14) which begin as follows:

'The whole charges of keeping and planting Greenewch parke wth the 16 Coppices and dwarfe Orchard for the space of these years, beginning at our Lady day [25 March] 1662 & ending at our La:day [25 March] 1665 and building the gardenhouse.'

So why the discrepancy in the financial accounts? And why does the Pepys Plan show two fewer coppices than the later plans? Is it possible that fourteen were originally intended, but a decision was made soon after to increase the number to sixteen? This raises the intriguing possibility that the Pepys Plan was copied with some modifications from a now lost masterplan or artists impression that was drawn in 1663 or 1664 shortly after Le Nôtre became involved and that the masterplan itself was based on one of a couple of years before. This seems all the more likely as Flamsteed's patron, Sir Jonas Moore, who commissioned the etchings from Thacker and Place was Surveyor General of the Ordnance and would almost certainly have access to any existing plans of the Park ... and why create an entirely new plan when an earlier plan could be easily adapted?

It would have been simple enough for Thacker or Place to copy the earlier plan, replace the Castle with the Observatory and scrub out the fountains from the Parterre. If this was the case, the failure to change the number of coppices from 14 to 16 requires explanation. Perhaps the exact number was considered unimportant. It is also possible, given their distance from the Observatory, that neither Thacker, Place nor Flamsteed realised that the number shown was no longer correct. Although it never happened, Flamsteed originally planned to publish all or most of the 12 Francis Place etchings in his Historia in the manner of earlier astronomers. As such, they were designed to show the Observatory in the best possible light. An earlier masterplan showing the avenues as complete would have suited Flamsteed's needs very well even if at the time of the Observatory's founding there were still many trees to be planted or re-planted.

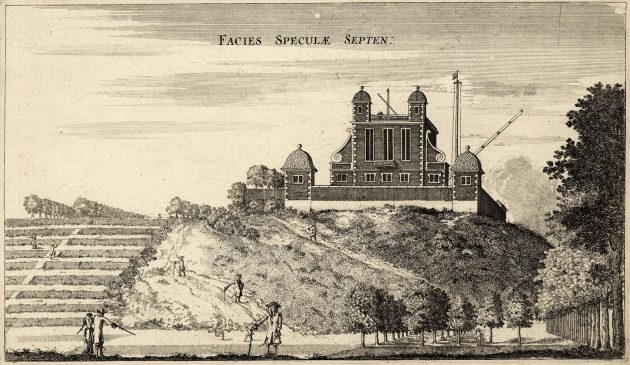

Whilst the Thacker/Place topographical views are generally considered to be be accurate representation of what existed when they were drawn, there are unexplained inconsistencies between some of the topographical views and the plan of the Park that went with them. One of these, the appearance of the snow well / ice house, has been mentioned already. Another is the appearance of the Giant Steps. The etching Facies Speculae Septen (below) shows the presence of nine risers on the Grand Ascent, whilst the plan shows twelve.

The Giant Steps (left) and the newly built Observatory (right). Facies Speculae Septen (North face of the Observatory), etching by Francis Place after Robert Thacker, c.1677. � The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.949

If the plan is based on one drawn in 1663 or 1664, and if, like the coppices, the number of steps constructed differed from the number originally planned, this could account for the discrepancy. It might also explain why the trees shown on the Parterre are not consistent with the layout on the plan (or indeed any of the later plans). The eching also shows the presence of what appears to be a ramp in the centre of each step. These are not shown on any of the plans or in any other known images except on another from the same series (Prospectus Orientalis). They may have been preparatory works for the cascade that was abandoned. Alternatively, and more likely, they are the remnants of the 'Staires' mentioned by Boreham in his financial accounts.

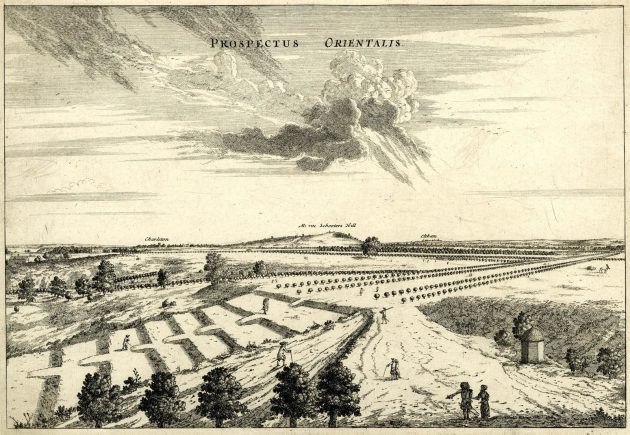

Lastly, in the view below (Prospectus Orientalis), Snow Hill Walk has been omitted and Pauls Walk (now Lovers Walk) has been misaligned. Unlike the other two differences, this one appears to be due to an inaccuracy on the part of the artist.

The Giant Steps as seen from the roof of Flamsteed House. Prospectus Orientalis (East Prospect), etching by Francis Place after Robert Thacker, c.1677. � The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.950

So what might all this mean for the way the ice house is depicted in the Pepys Plan? The most likely explanation is that it is how it was depicted on the earlier plans on which the Pepys plan was based and predates the works mentioned by Evelyn. Whether or not it was a true representation of the1620 structure is open to debate, not least because there seems to have been an asumption that the thatched structue over the well was circular (despite there being no record to indicate that this was the case).

So why does the Woodlands Plan show a similar structure? One possible explanation is that whoever drew it was using the Pepys plan as a reference. The conduit head on the Pepys plan is shown in 3D as a tunnel like structure with an arched roof in the same orientation as the ice house. On the Woodlands plan it is shown in exactly the same way as the ice house, but with a door on the north facing end.

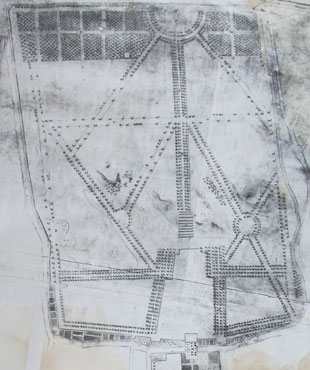

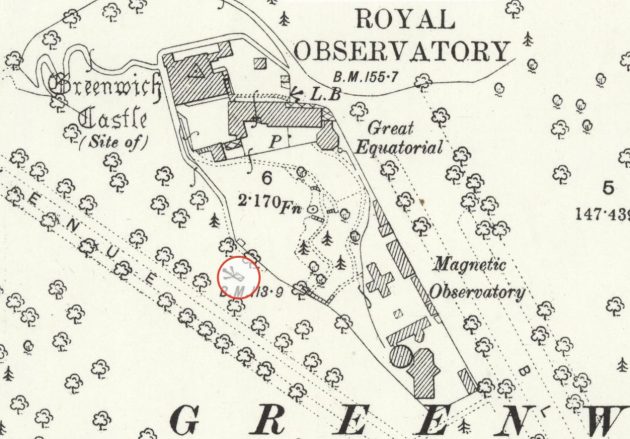

Airy's manuscript and published plans of the Observatory showing the location of the ice house

The 1847 Observatory plan. The ice house marked (r) has the appearance of a table tennis bat. It can be seen half way down on the left. The circular part has a diameter of roughly 30-feet. In the accompanying key, Airy called it 'An ice-house, belonging to the Ranger's House'. In the 1863 version he called it 'An Ice-house, belonging to the house of the Ranger of Greenwich Park'. Reproduced courtesy of Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek under a No Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Only license (see acknowledgements below for a link to the key)

The 1847 plan derives from a series of sketch plans that Airy began to draw soon after his arrival as Astronomer Royal in 1835. One dated 14 June 1836 is the first known Observatory plan to show the ice house (RGO6/54/15). However, it only shows the tunnel-like entrance which is labelled 'fountain' – a drinking fountain? A later plan (RGO6/54/17) is a coloured and carries the date of July 1837. Titled 'Plan of the ground inclosed in the spring of the year 1837 for the Royal Observatory, it appears to show not only the entrance, but also an underground tunnel leading directly away from it measuring roughly 10 by 45 feet in total. An undated plan of the grounds (RGO6/45/57) was probably drawn in 1846 as it bears a close similarity to the grounds as shown on the published plan of 1847. A key difference is that whilst on the published plan the extent of the well is shown by a single circle, on this plan it is shown by four concentric circles – presumably as a representation of the mound over the top of it (see next section).

Airy's correspondence with the Superintendent of the Park in the 1860s

On 30 May 1860, Airy wrote to the Chief Commissioner of Parks explaining that:

'Immediately outside of the pales [fence] of the Observatory Garden, there is a mound which covers the well of the Ice-House belonging to the Ranger’s House. This mound is about 5 feet higher than the general level of the ground. It serves therefore as a place for boys and idle people to stand on overlooking the garden and to throw stones into the garden. I have done all that is possible to defend the garden by raising the pales, but am still subject to great annoyance.' (RGO6/49/194)

He went on to ask if a fence of palings could be erected either round the base of the mound or half-way up it, and fitted with spikes and tenter hooks (angled spikes) to prevent people from climbing over it. Although steps were taken to alleviate the problem; instead of taking up Airy’s suggestion, thorn and briar stakes were driven into the top of the mound and a sign erected cautioning the public against throwing stones in the Park (RGO6/49/199). The stakes appear to have had the desired effect, but clearly needed a degree of maintenance as on 27 March of the following year Airy wrote again asking if ‘the thorn defence’ could be reinstated and preferably before Easter Day (RGO6/49/200). The urgency is interesting as it suggests that many people still came to Greenwich at Easter, despite the fact that the notorious Greenwich Fair, which had traditionally begun on Easter Monday, had been banned after the fair of 1857.

Today, much of the lower garden is laid to lawn with the lower area having been leveled. This leveling appears to have happened when Dyson became the new Astronomer Royal in 1910 and seems to have involved building a retaining wall at the bottom of the slope and building up the ground level.

Admiralty Plans of the Observatory published between 1885 and 1911

During the tenure of William Christie's tenure as Astronomer Royal, many new Observatory buildings were constructed and others altered. Between 1885 and 1911 the Admiralty (who funded the Observatory) published a series of five site plans at a scale of 66 feet = 1 inch, each being an updated version of the one before. Dated: 1885 (RGO7/50), 1891(WORK16/139), 1896 (WORK 16/139 & 16/1823), c.1905 (WORK17/369) and 1911 (WORK16/637), they all appear to derive from large scale town plans published by the Ordnance Survey, though only that of 1911 actually states that it was prepared and printed by the Ordnance Survey Office.

Each of the plans show the entrance tunnel into the ice house, which is drawn as a rectangle carrying a bench mark at its northern end and labelled 'Reservoir' (possibly because it was eroneously thought that it had the same purpose as the Standard Reservoir near Crooms Hill which was located roughly 250 yards to the east). By 1899 the entrance to the ice house had clearly either been demolished or buried as one copy the 1896 plan (WORK 16/139) has an extension to the path along the western boundary of the Observatory drawn in by hand and running right over the top of it. In the two later plans (c.1905 & 1911), the ice house was not removed before the path was added, so they too show its position relative to the path. Park records (Work 16/127) record that this extension was suggested as a park improvement in 1894. For those seeking to examine the site, it is on the bend just beyond a small padlocked gate in the railings bordering the left side of the path as you walk up it from the Avenue. The approximate GPS coordinates for the centre of the entrance tunnel are 51o28'38"N, 0o00'07"W (51.47718, -0.00176).

The tunnel entrance to the ice house is also marked on the 1840 Sayer Plan of the Park (WORK32/23) where it is labelled 'Conduit'. Within the Park, the Sayer Plan also marks the 'Standard Reservoir' along with 13 other conduits.

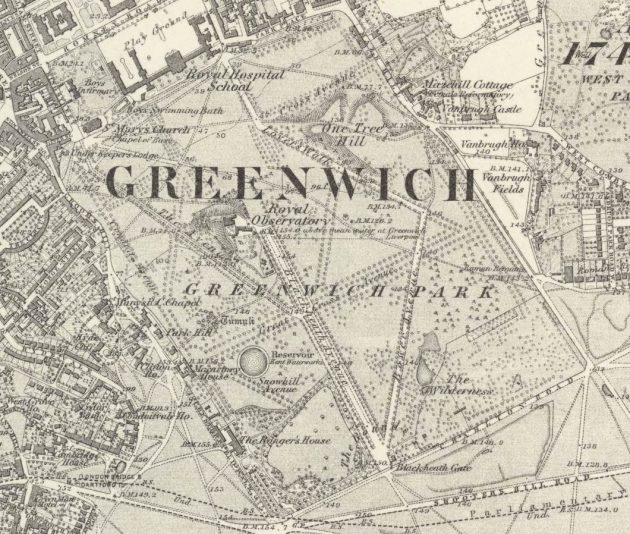

Ordnance Survey maps showing the entrance to the Ice House

The tunnel entrance and bench mark can be seen on the first three of the following large scale Ordnance Survey town plans whilst the mid-1890s path extension can be seen in the fourth. On the 1871 edition, the structure is marked 'Reservoir', but on those of 1851 and 1895 it is unlabelled.

Scale |

Surveyed |

Revised |

Published |

||

| 1:5280 | 1848-50 | - | c.1851 | link | |

| 1:1056 | 1867 | - | 1871 | link | |

| 1:1056 | 1893 | 1895 | link | ||

| 1:1250 | 1950 | - | 1951 | link |

The Observatory site c.1894 with the entrance to the ice house circled in red. Adapted from an extract from the Ordnance Survey 25-inches to the mile map, revised 1893 to 1894 and published in 1897. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license courtesy of the National Library of Scotland (see below)

The Ordnance Survey – a spreader of confusion or a guidng light?

The Great Cross Walk shown of the Travers Plan of 1697 is today known as Great Cross Avenue. The same cannot be said of Snow Hill Walk, which on John Rocques map of 1746 is labelled Brazen Face Walk and is now known as The Avenue. When the name changes took place is unclear, but it was clearly being called The Avenue by the 1870s as this is how it is labelled on the Ordnance Survey maps from that time. What seems rather curious is that those same maps label a previously unlabelled avenue of trees to the south of The Avenue as 'Snowhill Avenue'. Why this happened is not yet known.

In January 1894, when making various suggestions to the Ordnance Survey about changes that might be introduced in future editions of their maps, the Bailiff of the Park recommended the removal of the label Snowhill Avenue, not because it was wrong historically, but because 'The trees here are nearly all gone, and there is no appearance of an avenue' (Work16/127). This wish, along with others was granted.

Plan of Greenwich Park showing the relative locations of The Avenue (earlier known as Snow Hill Walk) and Snowhill Avenue in the 1870s. Detail from the 1:10560 Ordnance Survey Map, Middlesex Sheet XXIII, surveyed c.1867 & published c.1873. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence (see below)

Recommended 'Improvements' to the Park in the 1890s

In May 1894 a Committee, appointed by the Greenwich Vestry to enquire into and report on what further improvements were required in Greenwich Park, produced their report. It had nine recommendations. The fourth one read as follows and was later costed at £2,500 plus maintenance:

'That the splendid Terrace Walk round the Observatory which commands one of the finest views of the Thames from Woolwich to Westminster and their surroundings, requires the entrance from the clock on the east side made 10 feet wide (it is now barely 4 feet), the same width as the front, and continued down to the west side beyond the Ice Well. The whole of the front [north] side and west side of this hill requires to be thoroughly made up with earth and planted with shrubs.' (Work 16/127)

Based on the following article that appeared in the 7 December 1895 edition of The Daily News, the recomendation was acted upon although the path seems to have been widened by less than had been hoped:

'The funds which the importunity of Mr. Herbert Gladstone obtained from Parliament for the much-needed improvement of Greenwich Park have been in process of rapid expenditure this autumn, and there appears to be every reason to believe that the coming summer will find an immense improvement at two distant points in this beautiful old pleasure ground. About 500l. [£500] is being spent on a grand reformation of the slopes of Observatory Hill, which for very many years has been sadly disfigured by the much-abused freedom of scrambling about it hitherto conceded to the visitors to the park. There is to be no more of this liberty to do mischief. An immense quantity of earth has been deposited on the hillside to replace that which incessant scuffling about it has worn away, and which the rains have washed down, and the work will soon be in readiness for extensive planting of shrubs and other things naturally arranged. The whole hillside has been railed in, the zig-zag path up to the summit having been abolished. This, of course, is not the pathway leading up to the Observatory gates, which remains, and from the top of which a broad terrace affording a magnificent view will lead round the Observatory at the summit of the replanted slopes. This work is sufficiently advanced to render it tolerably sure thạt the spring will find it completed if the weather should prove at all favourable. ...'

The article failed to mention that the zig-zag path was where an anarchist bomb had exploded in February 1894. Nor was the any mention of the extension of the path that hugged the Observatory's western boundary which presumably was part of the works. Unfortunately, the records shed no light on whether the tunnel into the ice house over which it crossed was demolished, part demolished or buried.

Angus Webster – another spreader of confusion?

In 1902, Angus Webster, the Superintendent of Greenwich Park since 1897 published his book Greenwich Park: its history and associations. Experience has shown that much of what Webster says needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. He gives the date of a map published in 1749 as 'about 1695' and incorrectly states that trees were planted at the end of the Giant Steps from the date of their creation. Unfortunately, that did not stop the Royal Parks taking him at his word when the Giant Steps were recreated during the winter of 2023/24. This is what he had to say about snow wells and ice houses within the Park:

'[P.18/19] In an artificial hollow about midway between the Observatory and Crooms Hill, and hard by the road which intersects the ancient burial-ground, there is an old well, called the Snow Well, about 26 feet deep, the lower half lined with 16th century bricks, and near the surface with those of more recent date. At 4 feet from the bottom a small passage, about 4½ feet high and 30 inches wide, leads in the direction of St. Mary's gate. It was in this hollow that the post, or triangle, on which offenders were flogged, formerly stood, and which was in frequent use up to a late period. Although the hollow referred to is artificial, it is evidently of ancient date, as the oak trees growing on the slope of the hollow – which is much below the Park level – are at least 250 years old. In all probability the well was in use when the old and disused road (which was evidently at early times the principal thoroughfare through the Park) was in general use by the natives of Blackheath and Greenwich.

'[p.36/7] One Tree Hill was called " Sand Hill," and that on the west of the Observatory " Snow Hill," from the Snow Well there. From 1730 until 1850 the Park was much neglected. In 1854, the keeper's lodge, mentioned above, was taken down and the site thrown into the Park. The avenues were levelled and gravelled, and the steps on the Observatory Hill repaired; while the ice-house, on the same hill, has been filled in.

On the face of it, it would appear that Webster is writing about two different structures within the Park, one of which he calls a snow well and the other which he refers to as an ice-house. It should be noted however, that the hill to the west of the Observatory is labelled 'Crom' on the Pepys plan and 'Crum Hill' on the 1693 Gascoin plan. It is not named on the Travers plan (1697), the Sayer plan (1840), nor on any of the Ordnance Survey maps. It would seem that it was only called 'Snow Hill' for a brief while in the second half of the nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century.

Exploration of the conduits and tunnels under the park in 1905 & 1906

In September 1905, Greenwich Council sought permission from Webster to conduct a survey of the tunnels and conduits within the Park, their primary interest being any parts that extended under the roads that lay beyond the Park boundary and for which they were responsible. Various inspections took place over the following months. In their second report (which seems to be dated 31 October 1906), it was stated that amongst those they had inspected was

' A tunnel, mostly of brick but partly of stone work, leading from near the bottom of a brick shaft being in the depression sometimes called "The Whipping Place".' (Work16/1007)

No further details were given. Both this Report and Webster's book mention the Whipping Place. This may be why the Historic England research records about the snow well references this document (see below). However, according to Webster the ice house by the Observatory had been filled in by the time his book was published. We also know from the Admiralty plans that the entrance tunnel into it had been destroyed or buried in the late 1890s. So was the tunnel mentioned in the 1906 report another way in and if it was, why would an ice house have a tunnel of this size leading out from near its bottom? Or was it actually something completely different located elsewhere in the Park?

The tunnel mentioned in the 1906 report was possibly the same structure that Webster showed members of the West Kent Natural History Society two years later. A report on the visit in the 6 November 1908 edition of the Kentish Mercury records: 'An old well and curious passage leading from it were also examined'.

Both Webster and the 1906 report both say or imply that the Whipping Place was in a depression. There are few places withing the Park that could fit this description. They can be seen on this LiDAR scan of the Park. The most obvious is the one to the east of the Observatory which sits on the hillside close to 'Lovers' Walk' and is close to a surviving conduit head. A slight depression is shown near the entrance to the ice house by the Observatory and probably dates from the time when Snow Hill Walk was created in the 1660s. Minor depressions also exist on the hillside closer to Croom's Hill. One of these is roughly midway between the Observatory and Croom's Hill which seems to tally with what Webster was saying.

The orange pin shows the location of the depression where the whipping post may have been located. Detail from the 1:2500 Ordnance Survey Map, Edition of 1894�96. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence (see below)

A copy of an Ordnance Survey map of similar date (to the one above) in the possession of Dominic Clinton shows various conduits within the park including one about 40 metres long that leads from a shaft in the depression in roughly the direction of St Mary's Gate. If this was the location of the structure that Webster mentioned as being 'called the Snow Well', it is much more likely to be associated with the conduits in the Park than a snow well (this may be why Webster used the word 'called'). The shaft is shown on the plan as having a square profile, but in practice it is more likely to have been round. The route of the conduit is drawn with a thick line, making it difficult to gauge the width of the shaft from the plan. Webster is not much help either as although he tells us it was 26 feet deep, he failed to mention its width. It is not impossible that the shaft was originally dug as a snow well, but in the course of digging one of the many springs in the park was encountered which was then tapped and fed into the water supply system for the Palace.

An eighteenth century pen & wash drawing by Samuel Hieronymous Grimm – ice house or conduit?

A pen & wash drawing dated 1772 in the collections of the London Picture Archive by the Swiss artist Samuel Hieronymous Grimm carries the inscription Greenwich Park. It is described in their catalogue as a 'View of an ice house or conduit in Greenwich Park'. Although the image may well be the entrance into one of the many conduits, this did not stop the architectural historian Ellen Leslie stating, without qualification, in her 2010 article in Country Life, that it depicts the ice house constructed in 1619–20 – a claim that was subsequently repeated by the Ulster Archaeological Survey in their Survey of the ice house at Mount Stewart Demense.

View the image here on the London Picture Archive website

Historic England research records

The Historic England Research Records for the Snow Well draw heavily on Webster and need updating with the information from the Observatory records above. Towards the end of the record the following is recorded:

'An ice house of 1619-20 is very early in date and if it survived would be of considerable interest. Its appearance might have resembled the much later circa 1840 ice house at Scotney Castle, Lamberhurst (Grade II) which, unusually (and perhaps comparably), has a conical thatched roof. Unfortunately no trace of this structure was visible above ground in 1994 when the RCHME Greenwich Park Archaeological Survey was undertaken and it does not appear on any maps of the park.'

Greenwich Park Revealed

In September 2020, planning permission was granted for the Greenwich Park Revealed project. Part of the project involved archeological investigations in various parts of the Park. Initially, those running the project were keen to find the location of the ice house(s). They were unaware of the evidence in the Observatory records until March 2022 when this author shared them. Although it was hoped at the time that some sort of archaeological investigation might take place in 2023 or 2024, enthusiasm waned following the arrival of a new Park manager in April 2023. At the time of writing (July 2025), no investigation has taken place and the Greenwich Park Revealed Project has come to an end.

Further reading

The ice-house of Britain. Sylivia Beamon & Susan Roaf (1990)

Subterranean Greenwich – the website of Dominic Clinton and Per von Scheibner

Acknowledgements and Image licensing

The following etchings are reproduced under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license, courtesy of the The Trustees of the British Museum. They have been cropped, reduced in size and recompressed.

Graenwich: Museum Number: 1850,0223.254

Prospectus Australis: Museum number: 1865,0610.951.

Facies Speculae Septen: Museum number: 1865,0610.949

Prospectus Orientalis: Museum number: 1865,0610.950

The following image is © National Portrait Gallery, London and is reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence.

King Charles II by John Michael Wright. Oil on canvas c.1660-1665. © National Portrait Gallery.

Object ID: NPG 531

The plan of the Observatory grounds as they existed in December 1846 is reproduced courtesy of Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek under a No Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Only licence. It is taken from the 1845 volume of Greenwich Observations published in 1847. Key

The Ordnance Survey map extract (modified) showing the ice house is reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence courtesy of the National Library of Scotland. Click here for the complete map.

The Ordnance Survey map extract showing the whole of Greenwich Park is reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence. Click here for the complete map.

Thanks are also due to Andrew Wells for his help in transcribing the Exchequer Pipe Office declared accounts and to Dominic Clinton for sharing his expertise on the conduits and other subterranean structures within the Park.

© 2014 – 2025 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan