…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

People: John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal

Page under construction

| Employment dates |

29 Sep 1674 – 31 Dec 1719 (see note below re: start date) |

||

| Salary | £100 per year | ||

| Previous Posts | None | ||

| |

|||

| Born | 1646, Aug 19 | Denby, Derbyshire | |

| Died | 1719, Dec 31 | Flamsteed House. Burried: Burstow Surrey, 1720, Jan 12 | |

| Known addresses | 1646 | Denby, Derbyshire | |

| 1670–1675 | Queen Street, Derby | ||

| 1675 | Tower of London | ||

| 1675–1676 | Queen's House, Greenwich | ||

| |

1676–1719 | Flamsteed House, Royal Observatory Greenwich | |

| |

|||

| Additional Employment | 1684–1719 | Rector of Burstow |

|

| 1681–1684 | Gresham Lecturer | ||

| Various dates | Maths teacher | ||

| Wealth at death | Approximately £2000 | ||

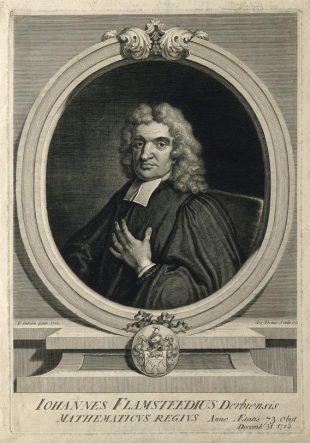

John Flamsteed. Line engraving by G. Vertue, 1721, after T. Gibson, 1712. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (see below)

Early life and appointment of Flamsteed as Astronomer Royal

The following account is derived from Agnes Clerke's entry for the National Dictionary of Biography (published in 1889) and was itself largely derived from a transcript of original documents belonging to Flamsteed that was published by Francis Baily in 1835 (An account of the Revd. John Flamsteed).

Flamsteed was born at Denby, five miles from Derby on 19 August 1646. He was the only son of Stephen Flamsteed, a maltster. His mother, Mary, daughter of John Spateman, an ironmonger in Derby, died when he was three years old.

He was educated at the free school of Derby, where his father resided. A cold caught in the summer of 1660 while bathing produced a rheumatic affection of the joints, accompanied by other ailments. He became unable to walk to school, and finally left it in May 1662. His self-training now began, and it was directed towards astronomy by the opportune loan of Sacrobosco's De Sphærâ. In the intervals of prostrating illness he also read Fale's Art of Dialling, Stirrup's Complete Diallist, Gunter's Sector and Canon, and Oughtre's Canones Sinuum. He observed the partial solar eclipse of 12 September 1662, constructed a rude quadrant, and calculated a table of the sun's altitudes, pursuing his studies, as he said himself, ‘under the discouragement of friends, the want of health, and all other instructors except his better genius.’

Medical treatment, meantime, as varied as it was fruitless, was procured for him by his father. In the spring of 1664 he was sent to one Cromwell, 'cried up for cures by the nonconformist party'; in 1665 he travelled to Ireland to be 'stroked' by Valentine Greatrakes. … He left Derby on 16 August, borrowed a horse in Dublin, which carried him by easy stages to Cappoquin, and was operated upon 11 September, 'but found not his disease to stir'. His faith in the supernatural gifts of the 'stroker', however, survived the disappointment, and he tried again at Worcester in the February following, with the same negative result, 'though several there were cured.'

His talents gradually brought him into notice. Among his patrons was Imanuel Halton of Wingfield Manor, who lent him the Rudolphine Tables, Riccioli's Almagest, and other mathematical books. For his friend, William Litchford, Flamsteed wrote, in August 1666, a paper on the construction and use of the quadrant, and in 1667 explained the causes of, and gave the first rules for, the equation of time in a tract, the publication of which in 1673, with Horrocks's Posthumous Works, closed controversy on the subject. His first printed observation was of the solar eclipse of 25 October 1668, which afforded him the discovery 'that the tables differed very much from the heavens.' Their rectification formed thenceforth the chief object of his labours.

Some calculations of appulses of the moon to fixed stars, which he forwarded to the Royal Society late in 1669 under the signature 'In Mathesi a sole fundes' (an anagram of 'Johannes Flamsteedius'), were inserted in the Philosophical Transactions and procured him a letter of thanks from Oldenburg and a correspondence during five years with John Collins (1625–1683)

About Easter 1670 he made a voyage to see London; visited Mr. Oldenburg and Mr. Collins, and was by the last carried to see the Tower of London and Sir Jonas Moore (Surveyor General of the Ordnance), who presented him with Mr. Townley's micrometer and undertook to procure glasses for a telescope to fit it.

On his return from London he made acquaintance with Newton and Barrow at Cambridge, and entered his name at Jesus College. His systematic observations commenced in October 1671, and 'by the assistance of Mr. Townley's curious mensurator' they ‘attained to the preciseness of 5". 'I had no pendulum movement',’ he adds, 'to measure time with, they being not common in the country at that time. But I took the heights of the stars for finding the true time of my observations by a wood quadrant about eighteen inches radius fixed to the side of my seven-foot telescope, which I found performed well enough for my purpose'. This was by necessity limited to such determinations as needed no great accuracy in time, such as of the lunar and planetary diameters, and of the elongations of Jupiter's satellites. He soon discovered that the varying dimensions of the moon contradicted all theories of her motion save that of Horrocks, lately communicated to him by Townley, and its superiority was confirmed by an occultation of the Pleiades on 6 Nov. 1671. He accordingly undertook to render it practically available, fitting it for publication in 1673, at the joint request of Newton and Oldenburg, by the addition of numerical elements and a more detailed explanation. An improved edition of these tables was appended to ,Flamsteed's Doctrine of the Sphere,/em included in Sir Jonas Moore's A new systeme of the mathematicks (1680).

A 'monitum' of a favourable opposition of Mars in September 1672 was presented by him both to the Paris Academy of Sciences and to the Royal Society, and he deduced from his own observations of it at Townley in Lancashire a solar parallax 'not above 10"'. His tract on the real and apparent diameters of the planets, written in 1673, furnished Newton with the data on the subject, employed in the third book of the

Principia; yet the oblateness of Jupiter's figure was, strange to say, first pointed out to Flamsteed by Cassini.

At Cambridge on 5 June 1674, he took a degree of M.A. per literas regias, designing to take orders and settle in a small living near Derby, which was in the gift of a friend of his father's. He was in London as a guest of Sir Jonas Moore's at the Tower from 13 July to 17 August and by his advice compiled a table of the tides for the king's use; and the king and the Duke of York were each supplied with a barometer and thermometer made from his models, besides a copy of his rules for forecasting the weather by their means. Early in 1675 Moore again summoned him from Derby for the purpose of consulting him about the establishment of a private observatory at Chelsea to be placed under his direction.

A certain 'bold and indigent Frenchman', calling himself the Sieur de St. Pierre, proposed at this juncture a scheme for finding the longitude at sea, and through the patronage of the Duchess of Portsmouth obtained a royal commission for its examination. Flamsteed was, by Sir Jonas Moore's interest, nominated a member, and easily showed the Frenchman's plan to be futile without a far more accurate knowledge of the places of the fixed stars, and of the moon's course among them, than was then possessed. Charles II thereupon exclaimed with vehemence that 'he must have them anew observed, examined, and corrected for the use of his seamen'. Flamsteed was accordingly appointed astronomical observator and directed 'forthwith to apply himself with the most exact care and diligence to the rectifying the tables of the motions of the heavens, and the places of the fixed stars, so as to find out the so much desired longitude of places for the perfecting the art of navigation', a royal warrant dated 4 March 1675, being subsequently issued for the payment of his salary. Although the warrant was issued in March, it instructed that Flamsteed should be paid 'quarterly, by even and equal portions, by the Treasurer of our said office, the first quarter to begin and be accompted from the feast of St. Michael the Archangel last past'; meaning that he was, in effect, employed from 29 September the previous year.

Text of the Warrant for paying Flamsteed's salary

The longitude problem

Back in 1675, although a sailor was able to measure his latitude – how far north or south he was – once out of sight of land, he had no means of measuring his longitude or how far east or west he was. As trade routes opened up, it became increasingly urgent to find a solution to the so-called longitude problem. The maritime nations of Europe offered a variety of large rewards or prizes for a solution.

Each 15° of longitude is equivalent to a difference in time of one hour. In theory then, in order to find out how far east or west he was from his homeland, all a sailor had to do was determine his local time from observations of the Sun or stars and compare it with the time back home at the same moment. This though was easier said than done. The idea of taking a clock to sea had been considered, but even the best were far too inaccurate to be of use. The improvements that came with the invention of the pendulum clock in 1657 were substantial and revolutionised astronomy, but on board a moving ship, a pendulum would beat irregularly and occasionally stop beating altogether.

Every hour, the Moon moves by about its own diameter against the background of stars. As early as 1514, Johann Werner of Nuremberg had suggested using the Moon as an astronomical clock. At that time however, star charts were too inaccurate and the precise motion of the Moon and the effects of refraction by the Earth’s atmosphere too poorly understood for the method to be practicable. It was not until the invention of the telescope, the pendulum clock, the micrometer screw and logarithms in the seventeenth century that astronomers became equipped with the tools they needed in order to begin to turn Werner’s idea into a practical reality. And this is what the Royal Observatory was founded to do.

John Flamsteed was put in charge and given the title ‘Astronomical Observator’. He later became known as the Astronomer Royal. Flamsteed realised that repeated measurements of the positions of the Sun, Moon stars and planets over long time periods was a prerequisite for understanding and predicting their motions. From its very foundation, the Observatory embarked upon systematic and long-continued programmes of observation. Until their interruption by the Second World War and the subsequent move of the Observatory to Herstmonceux these formed the Observatory’s most significant and most important contribution to astronomy.

Initially, as with observatories elsewhere, the work at Greenwich was confined to positional astronomy. From 1689 onwards, the most important of these measurements at Greenwich were made using specially designed telescopes aligned north south along their own Meridian. These could be pointed higher or lower in the sky, but could not be moved to point from side to side.

The measurement of star positions with meridian instruments is intrinsically linked to the measurement of time. The stars all move across the sky in a similar way to the Sun. As far as anyone could tell, the Earth was spinning at a steady rate, and this meant that each individual star would cross the meridian of one of the telescopes at the same (sidereal) time each day. In effect, the telescope was rather like the hand of a clock, whilst the stars were like the numbers around the dial. Certain of the brighter stars, whose positions had been refined by repeated observation over a long period of years, were used as ‘clock stars’ to determine the errors of the Observatory’s clocks and hence the local time at Greenwich.

Royal Warrant for the building of the Observatory

Buildings

Telescopes

7-foot Equatorial Sextant (1676)

Hooke's 10-foot Mural Quadrant (1676)

Specialist telescopes for observation of a single star:

Long’ refractors used in the Octagon Room:

‘Long’ refractors hung from masts and used in the garden and on the roof of Flamsteed House:

16-foot Mast Telescope (pre 1675)

60-foot Mast Telescope (c.1677)

27-foot Mast Telescope (c.1682)

Clocks

Other instruments

Published observations

When the Observatory was founded, there was no routine mechanism for publishing the observations or clarity as to who owned them. This led to lengthy feuds and long delays in their publication. The issue of ownership was finally resolved in 1765 when Maskelyne was appointed Astronomer Royal, and a set of regulations drawn up for the first time.

Flamsteed regarded the observations as his personal property and was keen to control both the manner and timing of their publication.The first volume of Flamsteed’s observations to appear in print was titled Historiae Coelestis Libri Duo. The story of how it came to be published is both complex, and acrimonious and resulted in Flamsteed having a lifelong feud with both Halley and Newton.

Funded originally by George Prince of Denmark, the consort of Queen Anne, and overseen by a committee of referees initially consisting of Newton, Christopher Wren, Dr John Arbuthnot, David Gregory and Francis Robartes, the Historia's printing began under the supervision of the bookseller Awnsham Churchill in May 1706, with the equivalent of 98 sheets (recorded by Flamsteed as 97 sheets) having been printed by December 1707. At this point, the press was stopped and following a dispute with the referees, Flamsteed was effectively cut out of the production process. Following the death of Prince George in 1708, production was funded by the Queen herself. Edited from this point onwards by Halley, the Historia was eventually published in 1712.

Historiae Coelestis Libri Duo (from ETH Zurich)

Historiae Coelestis Libri Duo (from Linda Hall Library)

Flamsteed’s observations for the years 1711-1713 were subsequently published without his consent by the Royal Society in their journal Philosophical Transactions:

Observationes cælestes Britannicæ, Grenovici in Observatorio Regio, a Johanne Flamsteedio, Ast. Reg. hahitæ, Annis MDCCXI & MDCCXII. Phil. Trans. R. Soc.28, 65–79

Observationes coelestes britannicæ, grenovici in observatorio regio habitæ, anno MDCCXIII. Phil. Trans. R. Soc.29, 285–294

In the draft of the preface to the Historia Coelestis of 1725 Flamsteed stated his disgust at how these observations had been treated:

‘This businesse being over, & Sir I.N. finding that his Visitation had not the effect he promised to himselfe, hee tooke care to let mee know, by the Secretarys letter as soon as the yeare 1711 was expired that the Royal Society (my Visitors) expected the copy of the observations of that year I returned an answer to him that they should have them in the time prescribed by the Order. & accordingly caused my Amanuensis, Jos. Crosthwaite to transcribe & leave them at their house in Crane court some dayes before midsummer 1712. I expected that they should have sent me a receipt for them: but Civil & just Sir I.N. esteemed it too great a favour for me. I did the same for the year following on a second letter, from the Secretary of the Royal Society & the next year 1713-1714 I found them both printed, abridged, & so spoyled by the Editor of my Catalogue that I would no longer owne them, for mine the most materiall observations were omitted, & the rest so managed that it seemed to me he had designed to spoyle them; out of Spight, he had inserted some that were imperfect, & given the Right Ascentions & distances of the Planets from the pole, deduced from the Observations but not their longitudes & latitudes this was too much drudgery for his acuteness {illeg}and who was used to procure what he published as his owe at easyer rates.…. After the same manner he got My observations of the yeare 1713 into his hands abridged, spoyled, and printed them in his Transactions for the year 1715 Numb 344.’ (RGO1/32C/91&92)

Of the 400 copies of the Historiae Coelestis Libri Duo that had been printed, 300 were acquired by Flamsteed following the death of Queen Anne in 1714 and Newton’s patron, the Earl of Halifax in 1715. After extracting the sextant observations – the only part of the volume that had been produced under his proper control, Flamsteed burnt the rest as a ‘Sacrifice to TRUTH ...saveing some few that I intend to bestow on you and such freinds as you that are herty lovers of truth that you may keep them by you as Evidences of the malice of Godless persons and of the Candor and sincerity of the freind that writes to you, and conveys them into [your] hands.’ (Flamsteed Correspondence, Vol 3, p.785 & 789 also in Baily’s An Account of John Flamsteed p.321).Several of these incomplete volumes are known to still exist.

The extracted pages were subsequently incorporated into Historia Coelestis Britannica, which was published posthumously in three volumes in 1725. Also bound into the volumes were the Francis Place etching of Flamsteed’s Equatorial Sextant which dates from c.1676 and a specially commissioned engraving by Emanuel Bowen of the Mural Arc, which probably dates from c.1724. An examination of the volumes held by different libraries and digitised by Google shows that there was no consistency as to which volumes, or where exactly in the volumes these two prints were inserted. Usually, but not always, they appear together in either volume 1 or volume 3. There are other difference in pagination that exist as well. For this reason, links to all the know digitised volumes (as of March 2021) are included below.

From Lyon Public Library (digitised 3 Feb 2012):

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 1

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 3

From Ghent University (digitised 9 July 2010):

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 1

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 3

From the Bavarian State Library (digitised 14 January 2011):

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 1

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 3

From the National Library of the Netherlands (3 volumes bound as 2, digitised 23 April 2014):

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 1 and part Volume 2

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2 cont. and Volume 3

From National Library Naples (Vol 1 in library catalogue, but seemingly not digitised. Vols 2 & 3 digitised 4 November 2013):

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 1

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 3

From the University of Turin (digitised 22 February 2016, Vol 2 only):

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 1

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 3

Also published posthumorously was the Atlas Coelestis which appeared after the Historias in 1729. The following high resolution copy comes from the Linda Hall Library:

See also:

A guide to the different sections of Flamsteed’s Historias

Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis and the etchings of Francis Place – a comparative study

Papers relating to the publication of the 1712 Historia

From the Macclesfield Collection, CUL (MS Add.9597/13/6/72a-87)

From Newton's Papers, CUL (t.b.c.)

Correspondence

As well as the published observations mentioned above, there are three main sources of information:

- Flamsteed's Correspondence, much of which survives. All the known letters (over 1,500) have been transcribed and published in three volumes under the title: The correspondence of John Flamsteed, with the final volume being published in 2002

- Flamsteed's manuscript observations (preserved at Cambridge),

- Papers published by the Royal Society in their journal

- Philosophical Transactions

Although much of Flamsteed's correspondence was in English, some was written in Latin and other languages. In the published correspondence, if a letter wasn't written in English a translation has also been provided. Many of the letters can be read as part of a Google preview. A search of the correspondence for the word eclipse reveals that Flamsteed was a great collector of eclipse observations from the extensive network of astronomers he was in touch with at home and abroad.

Although Flamsteed shared his own observations with his correspondents, he became rather less inclined to put his observations into print prior to the publication of his Historia. Indeed, Willmoth has noted (in her introduction to the third volume of Correspondence) that after 1706, Flamsteed never voluntarily allowed his name to appear in the Transactions. There seem to be only four occasions when his solar eclipse observations were published in the Transactions. These were for the eclipses of 1676, 1687, 1706 & 1715. Of these, only those made during the eclipses of 1676 and 1706 were published in any detail. Those for the 1676 and 1687 eclipse were published in Latin, but were republished by the Society in English in an abridged form in the early 1800s.

Solar eclipses observed at Greenwich

During the whole time that the Observatory existed (1675-1998), there was only one total eclipse that could potentially be seen from the Observatory itself. This was the eclipse which occurred in 1715 while Flamsteed was Astronomer Royal.

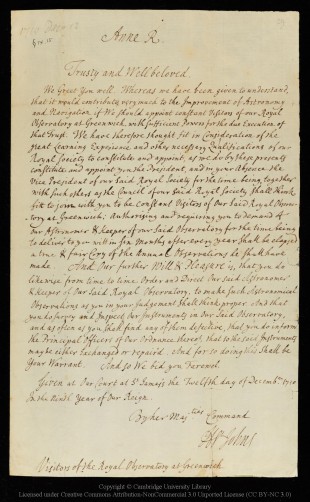

Contemporary transcript of the 1710 Warrant preserved amongst Newton's papers at the University Library Cambridge, MS ADD.4006/29 (for link see table below). Comparison with the actual Warrant preserved in the archives of the Royal Society, shows that apart from the obvious lack of original signatures and the Royal seal, there are also differences in spelling, capitalisation and punctuation as well as the occasional abbreviation of the word 'and' to '&'. Reproduced in compressed form under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC) licence courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library

Solar eclipses observed at Greenwich during the time of Flamsteed

The board of visitors

The appointment of Visitors to the Observatory was instigated by the president of the Royal Society, Sir Isaac Newton, who had been arguing with Flamsteed about the publication of his observations.

Although usually referred to as the Board of Visitors, the use of the term ‘Board’ only in fact came into use in the 1830s. The Board was set up by a Royal Warrant issued by Queen Anne on 12 December 1710. But for the Visitors to remain legally constituted, a new warrant was required on the accession of each new monarch. This was overlooked not only when Queen Anne died in 1714, but twice more on the subsequent deaths of King George I and King George II.

Burial and monuments

As well as being the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed was also Rector of Burstow from 1684 until his death at the end of 1719. His predecessor as Rector was his grand-father in law Ralph Cooke and his successor, James Pound, the uncle of the third Astronomer Royal, James Bradley. Although Flamsteed died in Greenwich at the Royal Observatory, he was taken to Burstow to be buried, the parish records indicating that he was interred there on 12 January 1720.

The only known record of exactly where Flamsteed was buried comes from the will of his wife Margaret. No monument or memorial was erected until the 1890s. Read more about Flamsteed's burial place and the monuments erected:

The Burial Place of John Flamsteed the first Astronomer Royal

Modern papers

Early Astronomical Researches of John Flamsteed. Eric Forbes, Journal for the history of Astronomy (1976)

An analysis of the errors in John Flamsteed’s mural arc observations. William Blitstein, Vistas in Astronomy Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 139-155 (1997) Addendum

The seven identified observations of Uranus made by John Flamsteed using his mural arc. William Blitzstein, The Observatory, vol. 118, p9. 219-222 (1998)

Flamsteed's lunar data, 1692-95, sent to Newton. N Kollerstrom, & B.D. Yallop. Journal for the History of Astronomy, p.237-246 (1995). Version with additional foreword

Acknowlegements

The 1721 image of John Flamsteed is reproduced in compressed form and at a reduced size courtesy of Wellcome Library, London (Public Domain Mark)

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan