…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

Solar eclipses observed at Greenwich during the time of Flamsteed (1675–1719)

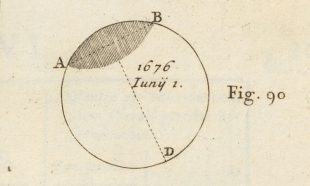

John Flamsteed. Line engraving by G. Vertue, 1721, after T. Gibson, 1712. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (see below)

Sources relating to Flamsteed's observations

As well as Flamsteed's manuscript observations (preserved at Cambridge), there are three main published sources of information:

- The three volumes of Flamsteed's Correspondence

- Papers published by the Royal Society in their journal Philosophical Transactions

- The two editions of Flamsteed's Observations i.e. the two Historias – Historiae Coelestis Libri Duo (1712) and the three volumes of Historia Coelestis Britannica (1725)

Although much of Flamsteed's correspondence was in English, some was written in Latin and other languages. In the published correspondence, if a letter wasn't written in English a translation has also been provided. Many of the letters can be read as part of a Google preview. A search of the correspondence for the word eclipse reveals that Flamsteed was a great collector of eclipse observations from the extensive network of astronomers he was in touch with at home and abroad.

Although Flamsteed shared his own observations with his correspondents, he became rather less inclined to put his observations into print prior to the publication of his Historia. Indeed, Willmoth has noted (in her introduction to the third volume of Correspondence) that after 1706, Flamsteed never voluntarily allowed his name to appear in the Transactions. There seem to be only four occasions when his solar eclipse observations were published in the Transactions. These were for the eclipses of 1676, 1687, 1706 & 1715. Of these, only those made during the eclipses of 1676 and 1706 were published in any detail. Those for the 1676 and 1687 eclipse were published in Latin, but were republished by the Society in English in an abridged form in the early 1800s. Where relevant, links to these are given below.

The story of how the Historiae Coelestis Libri Duo came to be published is complex and acrimonious and resulted in Flamsteed having a lifelong feud with both Edmond Halley and Isaac Newton. Funded originally by George Prince of Denmark, the consort of Queen Anne, and overseen by a committee of referees initially consisting of Newton, Christopher Wren, Dr John Arbuthnot, David Gregory and Francis Robartes, its printing began under the supervision of the bookseller Awnsham Churchill in May 1706, with the equivalent of 98 sheets (recorded by Flamsteed as 97 sheets) having been printed by December 1707. At this point, the press was stopped and following a dispute with the referees, Flamsteed was effectively cut out of the production process. Following the death of Prince George in 1708, production was funded by the Queen herself. Edited from this point onwards by Halley, the Historia was eventually published in 1712.

Following the death of both the Queen in 1714 and Newton’s patron, the Earl of Halifax, in 1715, Flamsteed was able to acquire 300 of the 400 copies that had been printed. After extracting only those pages that had been printed by the end of 1707 for reuse in an edition over which he had full editorial control (the edition of 1725), Flamsteed burnt the rest as a 'sacrifice to Truth' (Flamsteed Correspondence V3. p.789).

The so called pirated edition of the Historia published in 1712 contains measurements made by Flamsteed during solar eclipses up to the end of 1699. The 1725 contains those pages recycled from the 1712 edition only for those eclipses up to 1689. These appear in volume 1. The data for the 1693, 1694 and 1699 eclipses was printed afresh in a different format and published in volume 2. For these three eclipses, links to the relevant pages in both editions are given. For all the other eclipses, links are only given to the observations as they appear in the 1725 edition. Immediately after the Greenwich results for the eclipses up to and including the one that occurred in 1689 Flamsteed also published the observations that had been sent to him by observers.

For each of the eclipses, links are provided in the following order

- Flamsteed's Historia Coelestis Britannica

- Flamsteed's Historiae Coelestis Libri Duo (1693, 1694 & 1725 eclipses)

- Philosophical Transactions (if any)

- Correspondence (if any)

- Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

Before leaving this section, it is worth mentioning that the way that the solar eclipse observations were presented in the Historia by Flamsteed changed markedly over time leading to considerable variations in the amount of information printed. To start with written descriptions as well as timings and other measurements were given, from 1708 onwards however, the written descriptions were abandoned.

Timings of eclipses potentially visible at Greenwich courtesey of Fred Espenak and Chris O'Byrne

The eclipse figures below are computed for a point that is nominally in the centre of the Octagon Room using the following WGS84 coordinates and the Calculator by (EclipseWise.com)

Latitude: 51o 28' 40.8" N (51.47800o N)

Longitude: 0o 0' 6.9" W (0.00193o W)

Elevation: 52m

A time followed by (r) means the event was already in progress at sunrise, while a time followed by (s) means the event was still in progress at sunset. In such cases, the times and circumstances given are for sunrise or sunset, respectively. Eclipses which were observed are printed in black. Those that were not are printed in grey. There are several possible reasons why a particular eclipse may not have been observed. They include:

- cloud cover,

- a failure to predict them due to less refined methods of calculation,

- stubbornness after being told to observe them by the Board of Visitors,

- and absence from the Observatory (for example, Flamsteed may have been at Burstow where he had been Rector since 1684).

CalendarDateGregorian |

PartialEclipseBegins |

SunAlto |

MaximumEclipse |

SunAlto |

SunAzio |

PartialEclipseEnds |

SunAlto |

EclipseMag. |

EclipseObs. |

Note |

|

| 1675-Jun-23 | 03:46(r) | 0(r) | 04:27:53 | 5 | 58 | 05:22:08 | 12 | 0.67 | 0.583 | (1) | |

| 1676-Jun-11 | 07:50:23 | 35 | 08:51:10 | 44 | 110 | 09:56:41 | 53 | 0.335 | 0.218 | ||

| 1679-Apr-10 | 18:24:16 | 3 | 18:44(s) | 0(s) | 284 | 18:44(s) | 0(s) | 0.388(s) | 0.276(s) | ||

| 1682-Sep-01 | 17:14:19 | 13 | 17:23:41 | 12 | 268 | 17:33:06 | 10 | 0.014 | 0.002 | ||

| 1683-Jan-27 | 15:12:14 | 10 | 16:32:50 | 0 | 239 | 16:37(s) | 0(s) | 0.839 | 0.761 | ||

| 1684-Jul-12 | 14:16:36 | 51 | 15:27:36 | 41 | 252 | 16:32:57 | 31 | 0.615 | 0.523 | ||

| 1687-May-11 | 13:11:56 | 53 | 13:36:36 | 51 | 220 | 14:01:07 | 48 | 0.05 | 0.013 | ||

| 1689-Sep-13 | 15:24:50 | 25 | 15:57:34 | 21 | 248 | 16:29:22 | 16 | 0.109 | 0.042 | ||

| 1693-Jul-03 | 12:12:29 | 61 | 12:41:15 | 61 | 198 | 13:09:31 | 59 | 0.052 | 0.014 | ||

| 1694-Jun-22 | 16:22:11 | 33 | 17:03:15 | 27 | 274 | 17:42:16 | 21 | 0.17 | 0.08 | ||

| 1699-Sep-23 | 07:57:32 | 19 | 09:08:50 | 28 | 132 | 10:25:15 | 35 | 0.852 | 0.814 | ||

| 1703-Dec-08 | 15:35:20 | 1 | 15:47(s) | 0(s) | 232 | 15:47(s) | 0(s) | 0.117(s) | 0.047(s) | ||

| 1706-May-12 | 08:16:23 | 36 | 09:20:20 | 45 | 123 | 10:28:26 | 52 | 0.847 | 0.82 | ||

| 1708-Sep-14 | 06:34:23 | 9 | 07:28:52 | 17 | 107 | 08:26:40 | 25 | 0.493 | 0.385 | ||

| 1709-Mar-11 | 12:50:32 | 34 | 13:39:31 | 32 | 206 | 14:26:59 | 28 | 0.168 | 0.079 | ||

| 1710-Feb-28 | 11:37:08 | 30 | 13:05:46 | 29 | 195 | 14:31:10 | 24 | 0.682 | 0.585 | ||

| 1711-Jul-15 | 19:05:24 | 8 | 19:58:28 | 1 | 305 | 20:06(s) | 0(s) | 0.732 | 0.657 | (2) | |

| 1715-May-03 | 08:02:40 | 32 | 09:07:36 | 41 | 121 | 10:17:07 | 49 | 1.062 | 1 | (3) | |

| 1718-Mar-02 | 06:48(r) | 0(r) | 06:49:46 | 0 | 102 | 07:35:57 | 7 | 0.215 | 0.113 |

Notes:

- Clouded out, but a good description of the instruments Flamsteed planned to use survive (more on this below)

- Flamsteed was ordered to observe this eclipse by the newly formed Board of Visitors. It was not however observed (more on this below)

- Totality predicted to have lasted from 09:06:00 to 09:09:13 with a duration of 3m12s

Where the observations were made

The first solar eclipse after Flamsteed had been made Astronomer Royal occurred a few days before the Royal Warrant was signed for the Building of the Observatory. If the weather had not been cloudy, Flamsteed would have observed it from the Tower of London where his Patron Jonas Moore had provided him with accommodation. All the subsequent eclipses were probably observed from the Octagon Room which was the only observing space capable of accommodating his 16-foot telescope. However, some may have also have been observed from one or other of the two summer-houses when the projection method was being used. Flamsteed's description of the 1684 eclipse certainly implies that this was the case. Whether or not any eclipses were observed exclusively from the summer-houses cannot be determined from the published observations. A future examination of Flamsteed's observing books may shed further light on the matter.

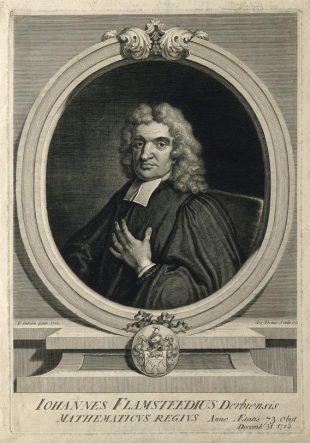

The Octagon Room as it appeared in Flamsteed's time. One of a series of etchings by Francis Place after Robert Thacker commissioned for Flamsteed c.1677–78. Key: (A) & (B) The two year going clocks with 2-second pendulums were made by Thomas Tompion in 1676 and presented to Flamsteed by Sir Jonas Moore. (C) A further clock about which little is known. (D) 3-foot moveable quadrant at the opening on the northern side of the room (F) Stand for supporting the eye-end of a telescope tube with a screw mechanism for adjusting its height (S) Ladder for supporting the object-glass end of the tube. (T) Telescope tube (with square cross-section). In this image, there does not appear to be a micrometer attached. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.952 (see below)

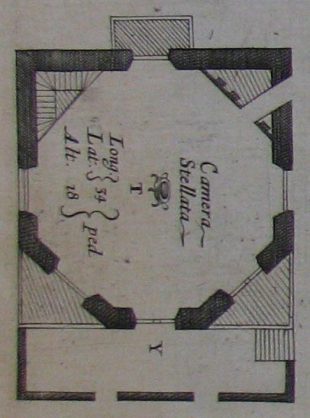

Floor plan of the Octagon Room. North at the top. Etching (detail) by Francis Place after Robert Thacker c.1677–78 courtesy of Greenwich Heritage Centre

Equipment used

Although all the eclipses observered after 1676 were timed by one of the two year-going clocks by Tompion that can be seen in the image above, at the time of the 1676 eclipse, they had still to be installed. Instead, Flamsteed used a clock with a 1-second pendulum that had been made for him by Tompion the year before and which he subsequently made use of in the Sextant House. To start with, the errors of the clocks in the Octagon Room were found using the 3-foot moveable quadrant to measure the altitude of the sun. From 1677 until 1679, the Hooke screwed Quadrant belonging to the Royal Society was used followed by Flamsteed's 50-inch Voluble Quadrant.

To start with, the instruments used to view an eclipses were recorded alongside the observations in the Historias. However, no such information was given for those that occurred from 1706 onwards. In the Octagon Room, Flamsteed's instruments of choice seem to have been his 16 and 8-foot tubes each fitted with a micrometer. He used a projection screen (Scenam or Scænam) on at least six occasions. In a letter to Hill, dated 28 April 1715, discussing the 1715 eclipse, Flamsteed informed him that he observed it on a screen 'not being able in the 69th year of my age to stand to a telescope to view the Eclipse though it'.

Instrument |

1675 |

1676 |

1684 |

1687 |

1689 |

1694 |

1699 |

1706 |

1708 |

1715 |

1718 |

|

| 23-foot tube | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 16-foot tube | ✓1 | ✓ | ✓3 | ✓ | ✓ | ? | ? | ? | ||||

| 8-foot tube | ✓2 | ✓3 | ✓4 | ? | ? | ? | ||||||

| 7-foot tube | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 3-foot glass | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 2-foot tube | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Projection screen | ✓5 | ✓6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓7 | ✓8 | ||||||

| Tompion 2-sec pend | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Tompion 1-sec pend | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Portable clock | ? | |||||||||||

| Unidentified clock | ✓ |

1 Also recorded as 196½-inches (16-foot 4½-inches) - the Telescopium Pedum Sedecin

2 Also recorded as 103½-inches (8-foot 7½-inches)

3 Described as Tubo Brev and Tubo Long

4 Described as 'Tubo pedum, fere, 8' i.e. about 8-feet long

5 Used with the 3-foot glass (Correspondence)

6 Used with the 2-foot telescope in a darkened room (Historia)

7 Used with the 7-foot telescope, which was also used visually (Transactions)

8 From correspondence

? No information given in the Historia

Of the eclipses observed, the greatest change in altitude between the beginning and end of an eclipse was 20o (1684). One of the current unknowns is how many people were required and what the protocols were for moving the telescope to a different rung of the ladder mid eclipse.

Eclipse magnitudes

In Flamsteed's time, the term 'digits eclipsed' rather than magnitude was used to describe the size of an eclipse. In 1760, Robert Heath gave the following definition of a digit in his Astronomia Accurata; Or the Royal Astronomer and Navigator:

'The twelfth Part of the Sun's Diameter, in solar Eclipses. In lunar eclipses the Moon's Digits eclipsed may be 23: all above 12 Digits showing how much of the Earth's Shadow more than covers the Moon's nearest Edge to the Middle of that Shadow, or Eclipse.'

Digits were sometimes divided into 60 minutes ('), which themselves were occasionally divided further into 60 seconds (").

What was measured and why?

Typical measurements including the time the eclipse began and ended, the time of mid-eclipse, the lucid parts, chords and cusps. The main reason for observing the eclipses was that they were a useful contribution to the pool of data being collected by Flamsteed for the improvement of lunar and solar theory – an essential prerequisite for the lunar distance method of measuring longitude to be turned into a reality ... and that after all, was the reason that the observatory had been founded.

For the total eclipse of 1715, Flamsteed also recorded the times of the start and end of totality. What he did not record during the total eclipse was the appearance of the Sun immediately before, during and immediately after totality. This was in marked contrast to Halley who observed the eclipse from Crane Court.

A note on dates and times

During Flamsteed's time, two different calendars were in use in Europe. Whilst England continued to use the Julian Calendar, much of continental Europe had switched to the Gregorian Calendar that had been introduced by Pope Gregory on 1582. The Julian Calendar and, the Gregorian Calendar have different rules for leap years and as a result the two calendars have gradually became more and more out of step. When the Observatory was founded the two calendars were 10 days out of step. This increased to 11 days in 1700. Today, most of the world uses the Gregorian Calendar, England having made the switch in 1752. Whilst Flamsteed used the Julian Calendar, some of his correspondents did not.

Not only were two calendars in use in Europe, but two different starts of the year were in use in England. Although the "Legal" year began on March 25, the use of the Gregorian calendar by other European countries led to January 1 becoming commonly celebrated as "New Year's Day" and given as the first day of the year in almanacs and in the Historias.

To avoid misinterpretation, both the 'Old Style' and 'New Style' year number was used by Flamsteed in his correspondence for dates falling between the new New Year (January 1) and old New Year (March 25), a system known as 'double dating'. Such dates are identified by a slash mark breaking the Old Style and New Style year, for example, 6 February 1702/1.

To complicate matters further, although the civil day began at midnight, astronomers began their days 12 hours later at midday. In the Historias, if an eclipse happened in the morning its recorded date was one day before the civil date. If it happened in the afternoon, the two dates were the same. If it straddled midday, then it was recorded under both dates. When writing to his correspondents, Flamsteed would often give the dates and timings in terms of civil rather than astronomical days

During Flamsteed's time as Astronomer Royal, apart from the hour-angle clock, all the clocks at the Observatory seem to have been set to show mean solar astronomical time (i.e.GMAT). Once recorded these times were corrected for clock errors and converted to apparent solar time, which was the time system that was then in use for predicting the times of eclipses .

Today, when writing about historic eclipses, dates are frequently given in terms of the Gregorian Calendar. In the sections below, the eclipse date is given in terms of the Gregorian Calendar (new style) followed by the equivalent date in the Julian Calendar (old style) together with the astronomical date where it is different. The dates given relating to any of Flamsteed's correspondence are those that appeared on the letters themselves.

The eclipse of 1675, June 23 (June 12)

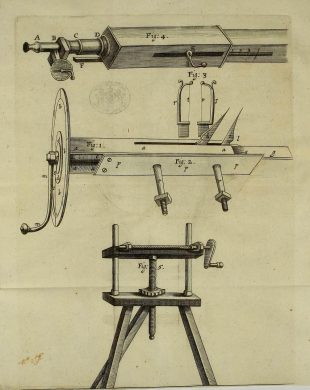

The screw micrometer was invented by William Gasacoigne. One based on his design and made by Richard Towneley (possibly the one shown here) was given to Flamsteed by Jonas Moore in 1670. From the drawing by Robert Hook published in 1667 in volume 2 of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in the library of the Natural history Museum Library, London. Downloaded from Internet Archive

'Wee are here busy in prepareing for the Solar Eclipse I am fitting up a three foot quadraant of my owne which I receaved lately out of the Country with a quicksilver level on the horizontall Radius and telescope sights of 3 foot: which I hope willl serve very well for Correcteing the clocks by. I intend to use two tubes. one of 23 the other of 7 foot with micrometers for determening the partes Eclipsed beginning and end, besides a 3 foot glasse to reaceave the species from it on a scene [a screen for receiving an image]. I doubt not but your are provides for it on Sunday morneing next, and that if the heavens blesse you with weather you will blesse us with your accurate observations' (Flamsteed Correspondence)

As things turned out, the weather was terrible as was explained by Flamsteed to Towneley in a further letter that he sent on 22 June after the eclipse:

'I am sorry to heare by yours of the 14th that your weather at Towneley was almost as ill as ours in London at the time of the eclipse. with us it was cloudy al night and the sun broke not forth next day till after noone. the cloudes came from the North which wee hoped might leave your heavens cleare: but the news of your letter has satified mee how vaine those hopes were and makes me feare my freinds in Derby shire who promissed to attend it had no better successe' (Flamsteed Correspondence)

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

The eclipse of 1676, June 11 (June 1 old style civil, May 31 old style astronomical)

This eclipse, which occurred in the morning, was an important occasion for the Observatory as not only was it the first solar eclipse that Flamsteed planned to observe there, but the King was also expected to be in attendance. At the start of the eclipse the Azimuth of the Sun was about 96o whilst at the end it was about 129o. Flamsteed took altitudes of the Sun for correcting the clock in both the morning and the afternoon. As a result, in the Historias, the observations straddle two days.

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 1 p.199-202 (1725)

Manuscript copy of the above sent to the Royal Society for publication

Mr. Flamsteed's Letter, concerning his Observations, and those of Mr. Townley, and Mr. Halton of the late Eclipse of the Sun. (Phil Trans R, Soc, abridged, Vol 2 p.316-319 (1809) – Abridged version of the above, but translated into English. Missing the obserations made to correct the clock

Flamsteed's letter to Oldenburg, 10 July 1676 (Flamsteed Correspondence Volume 1, p.478-485), no preview available. Includes a sketch

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

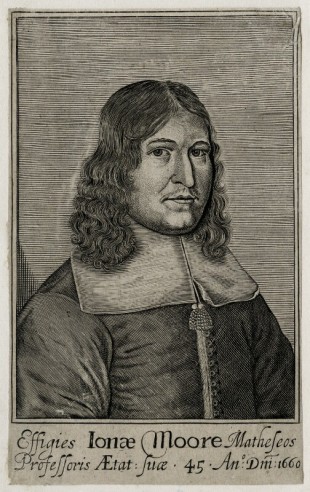

Jonas Moore after an unknown artist. Frontispiece to Moore's Arithmetick (1660). Line engraving © National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license (see below)

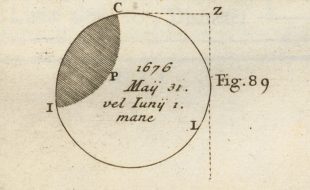

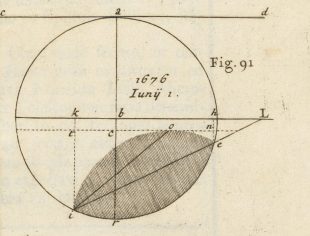

Figures 89, 90 & 91 from Flamsteed's Historia showing various stages of the eclipse. Engraved by John Senex and reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license courtesy ETH Zurich (see below)

In a letter to Towneley dated 27 May 1676 Flamsteed explained how he planned to prepare for the eclipse:

'I am now providing for the eclipse at which I intend to use a payre of tubes one of 16 the other of 8 foot for measuring the digits eclipsed and parts betwixt the cuspes. I hope you will doe the like. and be very carefull of your times in which I doubt not but I can be certaine to 10" seconds. I am now removeing my Astronomicall household stuffe from the Queens house to the Observatory where I have taken care to furnish my roome against the day of the Eclipse: at which the king intends to visit us and be present. Sir Jonas Moores Roome will also then be ready onley the house for the Sextant and wall Quadrant are not yet finished but will be in a short while.'

In the absence of the Great Clocks, Flamsteed made use of the second-beating clock (the future Sextant House Clock) that had been made for him by Tompion the previous year and that he had been using while making observations from the Queen's House.

What Flamsteed did not tell Towneley was that Sir Jonas Moore was also going to be in attendance as was Lord Viscout Brouncker the President of the Royal Society. Nor did he tell him that Edmond Halley would be assisting him with the observations.

As things turned out, the King did not attend and Moore missed out as Flamsteed was to explain to Oldenburg in a letter dated 10 July:

'The most eminent Surveyor of the Ordnance [Jonas Moore] came down here on the previous day in order to witness the observation of this eclipse. But since from sunrise until seven o'clock in the morning the thickest clouds covered all parts of the heavens, he believed that there would be no clear sky and returned to London before the clouds began to part. Although they deprived us of the beginning together with all the phases after 8.40, they nevertheless permitted me to obtain the visible position and latitude of the moon well enough, though not to discover its diameter accurately.' (Flamsteed Correspondence Vol 1, p.478-485)

He then went on to tell Oldenburg more about how the eclipse had been observed, much of which was repeated almost verbatim in his account that was later published in Philosophical Transactions:

'In conducting these observations, I was assisted by my friend Mr. Halley. We had prepared two tubes; the one 196½ inches long, having one of Townely’s micrometers, with which I took the measures of the first eight phases. The other was only 103½ inches long, with my own micrometer, and with which Mr. Halley took the observations. But in the last two observations, with this tube, (the micrometer of which is fitter for this use than the other) I took the distance of the azimuths falling by the sun’s lucid limb and the nearest cusp of the eclipse, while Mr. Halley in the mean time measured the lucid parts and the distance of the cusps, with the longer tube. A little before the beginning came Lord Viscount Brouncker, president of the Royal Society, who proved by his own judgment the measure of the sun’s diameter, taken with the longer tube. At 7h 45m the sun first appeared through the clouds.'

The two year-going clocks were probably installed a month or so after the eclipse on 7 July since a letter to Towneley dated 6 July 1676 (Flamsteed Correspondence) informs us:

' Wee shall have a payre of Watch clocks down here to morrow with pendulums of 13 foot and pallets partly after your manner. with which I hope wee may trie those experiments more accurately than with the second pendulum'.

Before leaving this section, it is worth noting that sources seem to differ as to when Flamsteed actually moved in to the Observatory. In the preface to his Historia of 1725 (Vol 3), Flamsteed states that he moved in August 1676. (Translation in NMM monograph No. 52 p113). In a letter to Edward Sherburne written on 12 July 1682, Flamsteed states that 'in Julye 1676 it was fit for habitation (See also Bailey p.126). Baily also quotes a memorandum of Flamsteed's in which Flamsteed supposedly says 'Entered it [the Observatory] in July 1676 (Bailey p.45).

The eclipse of 1684, July 12 (July 2 old style civil & astronomical)

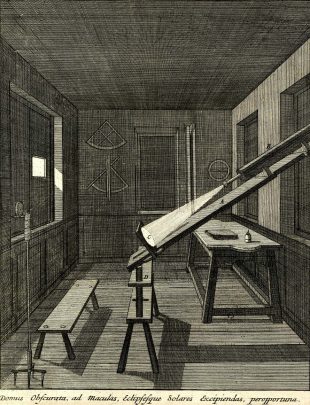

Domus obscurata ad maculas, eclipsesque solares excipiendas peropportuna (Darkened house very convienient for taking sunspots and eclipses). Key: (A) Adjustable support for he telescope and screen, (B) telescope for projecting the Sun’s image, (C) Screen onto which the image was projected, (D) Adjustable stand, similar in design to that in the Octagon Room above. Note also what appears to be a portable clock on the stand on the left. The telescope is pointing out of one of the two south facing windows that originally existed in the eastern summer-house. Etching (detail) by Francis Place after Robert Thacker c.1677–78 © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.953 (see below)

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 1 p.324 (1725)

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

The doctrine of the Sphere. John Flamsteed (1680)

The details as published in the Historia begin:

'Eclipsim Solis cum per Telescopium Pedum Sedecim, tum supra Scænam in obfcurato Conclavi, Observavi, Diameter Speciei per Telescopium bipedale supra Scænam transinissi erat 5.5 dig. pedis Anglicani, qui 16 Circulis Concentricis æquidistantibus in 32 minuta quot Solis est Diameter divisus, erat. Cælum Ante Meridiem Nubibus obductum, ut vix fpes erat Eclipsim observandi, circa Meridiem dehifcere cœperunt, & paulo ante Eclipsim dissipari 2h 4', Sol clarè confpectus integer apparuit; tunc nubibus iterum exceptus latuit usque 2h 12', quando ab iis prodeuntis ora Austrina deficere videbatur. Deinde fatis sereno Cælo observavimus,'

from which a rough English translation is as follows:

'I observed the eclipse of the Sun through a Sixteen Foot Telescope, and also on a screen in a darkened room. The diameter of the Specimen passed through a two-foot Telescope above the screen was 5.5 inches of an English foot, which was divided into 16 concentric circles equidistant in 32 minutes, as many as the Diameter of the Sun. The sky was covered with clouds before noon, so that it was hardly possible to observe the eclipse, they began to clear around noon, and a little before the eclipse dissipated at 2h 4', the Sun appeared clearly visible and whole; then again covered by clouds it remained hidden until 2h 12', when the eastern side seemed to disappear from them. Then we observed the fates in a clear sky,'

Howse (1975) took this to mean that the screen and two-foot telescope were housed in the domus obscurata in the eastern summer-house. This seems unlikely as the circumstances of the eclipse were such that much of it would not have been visible from this location due to the looming presence of Flamsteed House which would have blocked out the view between azimuths of about 208o and 258o. It is possible that the equipment was transferred for the occasion to the western summer-house which did have a suitable west facing window.

The eclipse of 1687, May 11 (May 1 old style civil & astronomical)

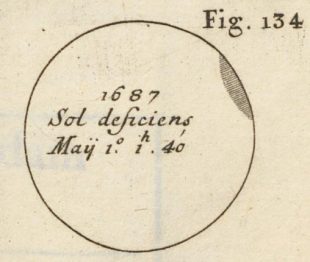

Figure134 from Flamsteed's Historia. Engraved by John Senex and reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license courtesy ETH Zurich (see below)

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 1 p.342 (1725)

Observationes nonnullæ Eclipseos Nuperæ Solaris … Phil. Trans. R. Soc.16:370–371 (31 Oct 1687)

Flamsteed also sent a copy of his observations in letter to Molyneux on 3 August 1687

Flamsteed also sent a copy of his observations in letter to Kirch on 17 October 1687

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

Writing to Newton on 27 April 1695, Flamsteed wrote:

'I have a solar Eclipse observed in May 1687 that will require a parallax less yet then your correction gives, by reason the Earth was then nearer the Aphelion,'

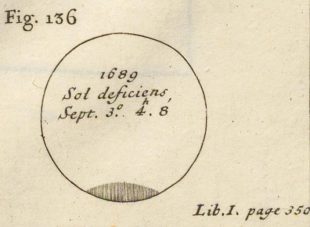

Figure136 from Flamsteed's Historia. Engraved by John Senex and reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license courtesy ETH Zurich (see below)

The eclipse of 1689, September 13 (September 3 old style civil and astronomical)

This minor eclipse took place in the afternoon. It began at an azimuth of about 241o and ended at an azimuth of about 255o.

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 1 p.350 (1725)

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

1693 Jul 3 (June 23 old style civil and astronomical)

This minor eclipse took place in the afternoon. It began at an azimuth of about 184o and ended at an azimuth of about 210o. Although it was not observed at Greenwich, Halley choose to included observations Flamsteed had received from Germany in the 1712 edition of the Historia.

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Libri Duo p.56 [534] (1712)

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

1694 June 22 (June 12 old style and astronomical)

This minor eclipse took place in the afternoon. It began at an azimuth of about 266o and ended at an azimuth of about 282o.

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2 p.232 (1725)

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Libri Duo p.61 [539] (1712)

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

The eclipse of 1699, September 23 (Sept 13 Old style civil, Sept 12 old style astronomical)

This eclipse took place in the morning. It began at an azimuth of about 116o and ended at an azimuth of about 153o.

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2 p.380 (1725)

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Libri Duo p.90 [568] (1712)

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

Letter from Flamsteed to Abraham Sharp dated 6 February 1702/1 (Vol 2 p.911), no preview available

In his letter to Sharp, Flamsteed wrote:

'At the Eclipse of the Sun Sept. 13. 1700 [1699] wee had here a thick fogg which broke up but some very few minutes before the end at 10h.32'.27" the limbe was not freed at 10h.32'.37" it was perfectly round. so I conclude the end at 10h.32½'...'

The eclipse of 1706, May 12 (May 1 old style civil, April 30 old style astronomical)

This eclipse took place in the morning. It began at an azimuth of about 107o and ended at an azimuth of about 145o. A detailed account (in English) was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (Vol. 25). For reasons that require further investigation, the figures given differ from those later published in the Historia. Both sets of figures also differ from those that Flamsteed sent Stanyan in a letter dated 24 May 1706.

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2 p.504 (1725)

Manuscript copy of the above sent to the Royal Society for publication

Draft of letter from Flamsteed to Stanyan dated 24 May 1706

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

The eclipse of 1708, September 14 (Sep 3 old style astronomical)

This eclipse took place in the morning. It began at an azimuth of about 96o and ended at an azimuth of about 119o. Flamsteed was at Burstow, where there were clear intervals only around mid-eclipse. Although this eclipse was also largely clouded out at Greenwich, some observations were made by James Hodgson. Hodgson's name was not however recorded as the observer in the Historia, but it was recorded by Flamsteed in a letter to Abraham Sharp.

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2 p.520 (1725)

Letter from Flamsteed to Abraham Sharp dated 14 September 1708

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

The eclipse of 1711, July 15 (July 4 old style civil and astronomical)

This eclipse took place in the evening. It began at about 19.05 at an azimuth of about 295o and ended at sunset at about 20.49 at an azimuth of about 315o while the eclipse was still in progress. In his An Account of John Flamsteed p.292, Francis Baily recorded the following entry in the Journal Book of the Royal Society for 24 May 1711:

'The President in the chair. The President ordered that Mr. Flamsteed be desired to make an observation of the future eclipse of the Sun, next July; and give it to the Royal Society, in compliance with her Majesty's letter to that purpose.'

Newton was both the President of the Royal Society and the newly established Board of Visitors and this is the first example of him using the powers granted to Board as set out in the Royal Warrant issued by Queen Anne on 12 December 1710. It was undoubtedly done in order to intimidate Flamsteed who might well have made arrangements to observe it anyway. It is worth noting that at this point in time, things were very tense between Flamsteed and Newton & Halley as the printing of the 1712 Historia was edging towards completion.

On 30 May A letter signed by Newton, Hans Sloane and Richard Mead was sent to Flamsteed with the order. As things turned out, Flamsteed did not observe it. Whether this was in defiance of Newton, because it was cloudy, or because Flamsteed was away in Burstow (where he was rector) we do not know. What we do know is that the Historia indicates that no observations of any kind were made after the 10 June until 14 July. There is also a gap in the surviving correspondence of Flamsteed over this time period.

Letter to Flamsteed dated 30 May 1711 ordering him to observe the eclipse (Flamsteed Correspondence Volume 3, p.717), no preview available.

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

The total eclipse of 1715, May 3 (April 22 old style civil, April 21 old style astronomical)

Flamsteed (right) with arm resting on a document showing his predictions for the 1715 eclipse. His Assistant Thomas Weston is close to the eye-piece of the Mural Arc whose horizontal limb carries the inscription 'Sharp fecit'. Detail from the ceiling of the Painted Hall in the Old Royal Naval College Greenwich (formerly Greenwich Hospital) by Sir James Thornhill. Commissioned in 1707 the painting of the ceiling was completed in 1712

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2 p.551 (1725)

Letter to Flamsteed to Hill dated 28 April stating that he observed the eclipse on a screen

Letter from Flamsteed to Abraham Sharp dated 11 October 1715 containing his observations

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

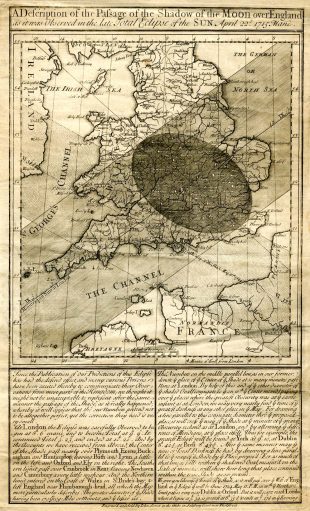

Shortly after the eclipse, Halley issued this second map showing the actual path of the 1715 eclipse together with the predicted path of the total eclipse due in the evening of 11 May 1724. Engraved and sold by John Senex. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence courtesy of the Institute of Astronomy Library, Cambridge (see below)

At the start of his subsequent paper in Philosophical Tranactions Halley explained his reason for producing his map of the predicted path:

'The Novelty of the thing being likely to excite a general Curiosity, and having found, by comparing what had been formerly observed of Solar Eclipses, that the whole Shadow would fall upon England, l thought it a very proper Opportunity to get the Dimensions of the Shade ascertained by Observation; and accordingly I caused a small Map of England, describing the Track and Bounds thereof, to be dispersed all over the Kingdom, with a Request to the Curious to observe what they could about if, but more especially to note the Time of Continuance of total Darkness, as requiring no other Instrument than a Pendulum Clock with which most Persons are furnish’d, and as being determinable with the utmost Exactness, by reason of the momentaneous Occultation and Emersion of the luminous Edge of the Sun, whose least part makes Day.'

In has account of the 1676 eclipse, Flamsteed described Halley as his friend. By 1715 things were very different because of their falling out over the publication of the Historia. Their mutual loathing is plain to see in the way that they wrote about each other in their accounts of the total eclipse. In his account Halley wrote:

'The near Agreement of this Observation [James Pound's] with our own (the Difference being only what is due to the Difference of our Meridians) makes us the lets solicitous for what was noted at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, from whence we can only learn that the Duration of Total Darkness was 3’,11".

As if in response, in his letter to Sharp, after giving him his observations at Greenwich, Flamsteed went on to say:

'Dr Halley makes all thes phases to have hapned some few seconds later than they were noted here, wheras Crane Court lies about halfe a minute of time Westwards of us. and all the times ought to have been near as much later there than here so that I feare thew was an error in his quadrant of about 4 minutes, and it shewed the suns heights so much too great ... But Mr Whiston told me that their clocks were set by Mr Tompians Meridian line which I gave him many yeares agone and I suspect he never allowed for the difference of Meridian betwixt the Observatory and his house and this is probably the Cause why the times taken at Crane Court agree so nearly with those taken here. Mr Pounds his Quadrant I fear had the same fault with that at Crane-Court; or the Dr made his times to agree with Mr Pound's. as for the Dr rants or twits I never did nor ever shall take notice of them till he ceases to think himselfe a wit, or becomes an honest and gratefull man:'

The eclipse of 1718, March 2 (Feb 19 old style civil. Feb 18 old style astronomical)

This eclipse took place in the morning. It began at sunrise with the eclipse already in progress at an azimuth of about 93o and ended at an azimuth of about 111o.

Observations as published in Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2 p.563 (1725)

Eclipse Map (from Eclipsewise)

Acknowledgements and Image licensing

The 1721 image of John Flamsteed is reproduced in compressed form and at a reduced size courtesy of Wellcome Library, London (Public Domain Mark)

The image from the British Museum of the Octagon Room (Museum number: 1865,0610.952) is reproduced under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license, courtesy of The Trustees of the British Museum. The Image has been cropped and resized for this website.

The image from the British Museum of the domus obscurata (Museum number: 1865,0610.953) is reproduced under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license, courtesy of The Trustees of the British Museum. The Image has been cropped from the original for this website.

The portrait of Sir Jonas Moore after unknown artist. Line engraving, published 1660. © National Portrait Gallery, London. National Portrait Gallery Object ID: NPG D42258 is reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license.

The three diagrams of the eclipse of 1676 are reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license) license courtesy ETH Zurich and are taken from the 1712 edition of Flamsteed’s Historia (https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-79201).

The 1715/1724 eclipse map is reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence courtesy of the Institute of Astronomy Library, Cambridge. Link to original high resolution image.

© 2014 – 2025 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan