…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

Christie’s ‘Lady Computers’ – the astrographic pioneers of Greenwich

The first women to be employed at the Royal Observatory in a professional capacity were Isabella Clemes, Alice Everett, Harriet Furniss, Edith Rix and Annie Russell. They were all employed as ‘Lady Computers’ between 1890 and 1895. Although the stories of Alice Everett and her Girton contemporary Annie Russell (later, Mrs Maunder) have been retold many times, those of the other three have languished in obscurity, as has the true reason for their employment.

All five women became members of the British Astronomical Association, but only Russell became a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society. Although she was not the first woman to be elected, it was her hitherto unrecognised influence that caused the Society to obtain the Supplemental Charter that gave women the undisputed legal right to become Fellows for the first time in 1916.In this tangled tale, which draws on significant new research and seeks to correct earlier misunderstandings, we discover that Rix attended an orphanage school even though she wasn’t an orphan and at the age of nineteen became a lifelong friend of Lewis Carroll who, in 1885, dedicated a work to her. Clemes on the other hand, was orphaned at the age of four, was the grand-daughter of a hatter, and was committed to an asylum within two years of starting work at Greenwich.

The whole story gets curiouser and curiouser the more deeply one delves. With significant papers missing from the archives and important data not entered in certain key registers, a conspiracy theorist might well speculate that the Observatory and Royal Astronomical Society had something to hide, rather than to celebrate.

Staffing problems in the late 1880s

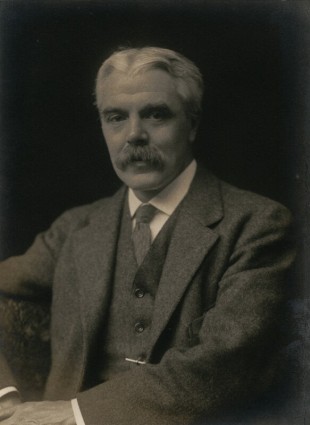

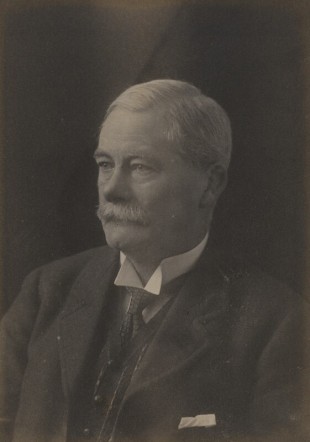

By 1888, the new Astronomer Royal, William Christie had been in office for seven years and overseen a considerable expansion in the number of large telescopes both deployed and planned. But the number of staff both permanent and temporary had remained essentially unchanged.

Large telescopes acquired by Christie |

First agreed |

First light |

|

| Lassell 2-foot Reflector | 1883 | 1884 | |

| 28-inch Photo Visual Refractor | 1885 | 1893 | |

| 13-inch Astrographic Refractor | 1888 | 1890 | |

| Thompson 9-inch Photographic Refractor | 1890 | 1891 | |

| Large Altazimuth | 1892 | 1896 | |

| 26-inch Thompson Refractor | 1894 | 1897 | |

| 30-inch Thompson Reflector | 1895 | 1898 |

The staffing problem was raised by Christie at the annual meeting of the Board of Visitors, in June 1887 and again in June 1889. He ended his Reports as follows:

1887:

‘I believe that the maximum of efficiency at the minimum cost would be attained if an increase of work were met by an increase in the staff of computers, with due recognition of the position of two or three senior computers, and of the increased responsibility of the Assistants.’

1889:

‘In order to meet the pressure of computing work, the Admiralty have authorised an addition to the grant for Computers, and their number has accordingly been increased; but this does not meet the difficulty felt in providing for the proper supervision of the growing work of the Observatory, which can hardly be carried on efficiently unless some means are taken to strengthen the supervising staff.’

The table below shows the number of posts of different classes at the Observatory between 1887 and 1898.

Post |

1887 |

1888 |

1889 |

1890 |

1891 |

1892 |

1893 |

1894 |

1895 |

1896 |

1897 |

1898 |

|

| Chief Assistant | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 1st Class Assistant | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | – | – | – | |

| 2nd Class Assistant | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3* | 3* | – | – | – | |

| Assistant | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Higher Grade Estab. Computer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Established Computer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ** | 4* | 5*** | |

| Supernumerary Computer | 13 | 14 | 17 | 19 | 17 | 18 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 24 | 23 | |

| Total+ established staff | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

* 2 vacancies ** 6 vacancies *** 1 vacancy

+ excludes a civil service 2nd division clerk carrying out administrative duties

Figures are taken from the Annual Report (written at the end of each May)

The two Established Computer Grades were only introduced in 1896. All references to Computers on this page are to the Supernumerary Computers unless specifically stated otherwise.

Extra Computers were all very well (their number to rose from 14 in 1888 to 23 in 1893), but what Christie really wanted at the start of 1890 was more assistants to help run the new telescopes and for this there was no immediate prospect of money being provided. With the Astrographic Telescope expected to be delivered in the early spring (of 1890), he made the decision to ‘experiment’ and employ ‘Lady Computers’ to staff the new Astrographic Department he was about to set up under the superintendence of George Criswick. Only women who had attended a University Ladies’ College at Cambridge were employed. A total of four were taken on. They were Isabella Jane Clemes, Edith Mary Rix and Harriet Maud Furniss from Newnham and Alice Everett from Girton. They were all unmarried. Christie’s plan, it would seem, was that they should operate as a team under the supervision of Clemes, who was roughly 20 years older than the others. An entry in the Journal of the Chief Assistant (Herbert H Turner) tells us that all four started at the Observatory on 14 April 1890 and that they were initially set to work on re-computing the transit observations from 1886 (RGO7/29).

Although it is not known why or when Clemes resigned, she had definitely left by 7 October 1891 and most probably before the end of 1890. She was committed to Bethlem Hospital in 1892 and does not appear to have been replaced. Furniss resigned for reasons unknown on 31 January 1891 and was eventually replaced on 1 September by Annie Russell (RGO7/29, RGO7/140 & RGO7/29), a contemporary of Everett’s at Girton. Rix resigned in March 1892 on health grounds and was not replaced. The employment of women came to an end in 1895. Everett secured a position at the Observatory in Potsdam and left the Observatory on 5 July. Russell resigned a few months later on 31 October (RGO7/29/156) and married her colleague E Walter Maunder at the end of December. More detail is given below about the resignations, the attempts to find replacements and the ultimate ending of Christie’s ‘experiment’.

Name |

College |

MathematicalTripos* |

Start date |

Start

|

Monthlystartingsalary** |

Leave date |

|

| Clemes | Newnham | Jan 1881, senior optime | 1890, Apr 14 | 43 | £8 | 1891? | |

| Everett | Girton | Jun 1889, senior optime | 1890, Apr 14 |

25 | £6 | 1895, July 5+ |

|

| Rix | Newnham | Jun 1889, did not sit exam | 1890, Apr 14 | 24 | £4 | 1892, Mar 7+ | |

| Furniss | Newnham | Jun 1889, aegrotat | 1890, Apr 14 | c.23 | £4 | 1891, Jan 31+ | |

| Russell | Girton | Jun 1889, senior optime | 1891, Sep 1 |

23 | £4 | 1895, Oct 31+ | |

| * | Students were graded wrangler (first class), senior optime (second class) and junior optime (third class). Aegrotats were awarded to those who would have reached the required standard, but were unable to undertake their exams due to illness. In the early days, a considerable number of Newnham students did not attempt the tripos |

| ** | RGO7/140/115 & 73–4 |

| + | Dates from RGO7/266 and RGO7/140 |

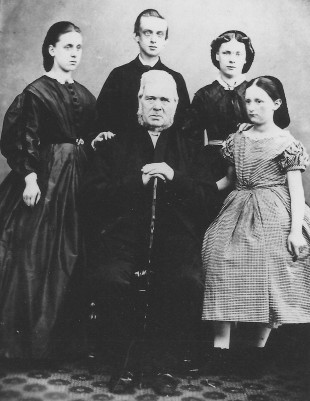

Isabella Clemes (left) with her brother Samuel, who is standing behind their grandfather William Clemes (seated). To his right are his grandnieces Harriet and Juliet Dunster. From a photograph taken in St Austell in the 1860s courtesy of Catherine Sheldon Lazier

Prior to 24 February 1881, women were not formally allowed to sit the Tripos exams, and could only be examined though a private arrangement with the examiners. If successful, they were awarded neither a certificate nor a degree by the University. After this date they had the automatic right to be examined and awarded certificates, but had to wait until 1923 to be awarded titular degrees and 1948 to be admitted to formal membership of the University and be permitted to graduate in the same manner as men.

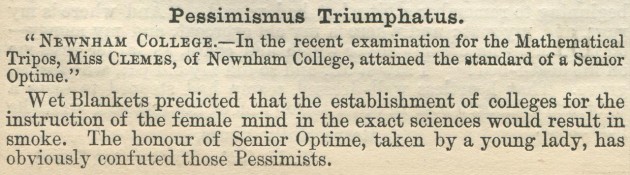

The changes in 1881 came about following a special congregation that took place on 24 February at the University’s Senate House. It was there that a vote took place on the findings of a report of a Syndicate appointed in June 1880 (following the sensation caused by the success of Charlotte Scott in the January 1880 Mathematical Tripos exams where she beat most of the 102 men by coming eighth equal in the overall rankings) ‘to consider certain memorials as to the higher education of women’. The report which recommended, that subject to certain conditions of residence, female students should be admitted to the Tripos Examination and certificates issued, had previously been discussed at a meeting of the senate on 11 February. The proceedings of that meeting were reported in The Times on 14 February and were the subject of an extensive editorial in the paper on the following day. In the meantime, the results of the 104 men awarded a degree in the 1881 Mathematical Tripos had been published in The Times on 29 January, those of the four Girton Women on 1 February and that of the sole Newnham Candidate, Isabella Clemes, on 7 February. The success of Clemes was linked with the ongoing discussions in the Senate by the satirical magazine Punch, which on 19 February published the short paragraph titled Pessimismus Triumphatus that is reproduced below.

Pessimismus Triumphatus from the 19 February 1881 edition of Punch. The quote at the start is lifted directly from the 7 February edition of The Times. Prior to 1881 only twelve women are believed to have sat and passed the Cambridge Tripos. Of these, just three came from Newnham

A brief biography of each of the five women can be found towards the bottom of the page.

The mystery of the missing records

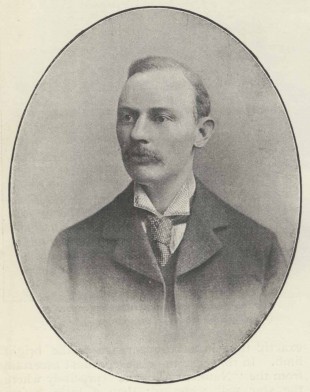

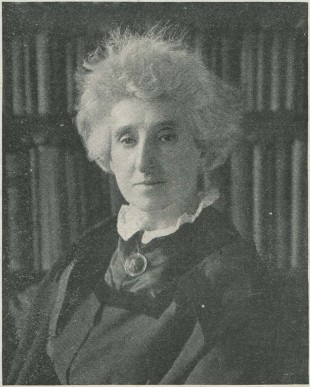

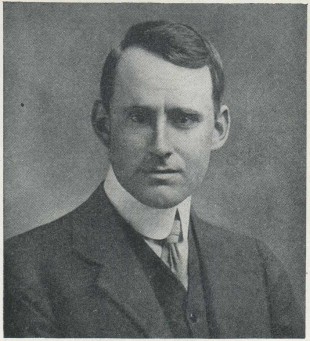

Alice Everett. Print by Andre & Sleigh from a photograph by Morgan & Kidd, Greenwich. From the 22 November 1893 edition of The Sketch

Even stranger, although the Observatory kept a Register of Computers, only the names of the two Girtonians (Everett and Russell) were entered (RGO7/266). As well as stating that both women worked in the Astrographic Department, it also states that Russell worked in the Heliographic Department. However as it is not possible to tell when this second piece of information was added; it is not clear if she was jointly assigned to the Heliographic Department from the start, or, (as seems more likely from the published observations and the Astronomer Royal’s 1892 Report), if she was assigned there at a later date, possibly in 1892. Although both women are listed as having obtained observing certificates for the Astrographic Telescope, neither is listed as having an observing certificate for the Photoheliograph. The evidence from their testimonials however indicates that this was an omission (RGO7/138). Information published elsewhere in Greenwich Observations (see below) makes it clear that irrespective of her involvement with the Heliographic Department, Russell was one of the individuals tasked with taking photographs with the Astrographic Telescope in 1893, 1894 and 1895. The names of the various women were also omitted from the list of computers awarded observing certificates (RGO7/136).

Although it is possible to think of a range of reasons from the innocent to the malign as to why individual documents may be missing from the archive and don’t appear in the catalogue, it is much more difficult to come up with a viable reason as to why the names of the three Newnham women were not entered into the Register of Computers, or why none of the women’s names appear in the list of computers awarded observing certificates.

In the case of Clemes, the only material that has been located in either the Observatory archive or Greenwich Observations that mentions her by name is the entry (mentioned above) in the Chief Assistant’s Journal giving her starting date and the following entry on a list of the four women’s salaries in the Lady Computer file: ‘Miss Clemes £8 a month’ (RGO7/140/115).

The intended role of the women

At the time of writing, the only known contemporary references (published or otherwise) to explicitly spell out the proposed role of the women are four brief articles (and/or their derivatives) that were published in 1890 and 1891. The first, titled Women at the Royal Observatory was published in the Pall Mall Gazette on Wednesday 23 April 1890 (and copied almost verbatim in a number of other papers and journals including: the Local Government Gazette on 24 April, the Aberdeen Journal on 26 April and The Leeds Mercury on 10 May). The second was published in The Times on 9 June 1890 and was a report about the annual visitation at the Observatory that had taken place two days earlier. The third was published in the Liverpool Mercury on 10 June 1890 and has the appearance of having been derived from the earlier report in The Times, but with some additional editorial comment. The fourth was an article by Isabella Clemes titled Woman’s place and work that was published in America on 20 June 1891 in The Churchman. The four articles are reproduced in full and in part below:

From the Pall Mall Gazette (23 April 1890)

‘It is not generally known that a department has been recently opened at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, which is presided over entirely by women. Four ex-Newnham students, at the head of whom is Miss Clemes, a lady who was for some years resident in Manchester, are engaged in daily work at the Observatory. Their employment includes exact measurement from photographs, as well as actual photography and night observations. The arrangement is said to be only tentative, but if Miss Clemes and her associates succeed in making themselves useful the Women’s Department will doubtless become a permanent institution.’

From The Times (9 Jun 1890; p.12)

‘From the report [to the Board of Visitors] we learn the Admiralty have sanctioned the building of a store-house for the various portable instruments. The original idea was to have a building of one storey, but the Astronomer Royal now considers it desirable to modify this idea and erect a two-storey building, and thus provide additional computing-rooms, and also bed-rooms for the observers. In the olden days bed-rooms were provided, but Sir G. Airy found they were not needed and abolished them about 50 years ago; but the introduction of ladies as observers renders it necessary to revert to the old plan.

…

At present the staff consists of nine assistants, a second division clerk, and 12 computers. Of the 12 computers four are ladies, who have recently joined, and who may by described as students, as they are to be taught theoretical astronomy and to take and measure the photographs for the chart of the heavens. As these duties will involve attendance at all hours of the night, the necessity for sleeping accommodation will be at once evident, This is a new opening for ladies who have received a higher education, and doubtless when the Government sanctioned their employment, it was with a view to testing the capabilities of ladies for office and scientific work.’

From the Liverpool Mercury (10 June 1890)

‘The success of the ladies at the Cambridge mathematical examinations confirms the wisdom of a new departure at the Royal Observatory Greenwich. The Government recently decided to appoint two additional assistants to meet the increase of work to relieve the chief assistant of some of the duties of supervision [not true]. The staff now consists of nine assistants, a second division clerk, and twelve computers. Of the latter, four are ladies who have recently joined, and they are to be taught theoretical astronomy, and to take and measure photographs for the new chart of the heavens. This is a new opening for ladies who have received a higher education, and when the Government sanctioned their employment it was, no doubt, with the view of testing their work capabilities for office and scientific work. We do not believe there is the slightest reason to fear that the experiment will be a failure. Higher education has developed and is developing faculties which in the old days of imperfect culture were not supposed to exist; but it is obvious that great attainments would be of little value if they were not capable of practical application, and the step taken by the authorities at Greenwich in supplying a test is, therefore, worthy of all commendation.’

From The Churchman, Vol 63 p.987 (20 June 1891)

In writing of “Women’s Work in the Greenwich Observatory,” in England, Isabella J. Clemes says:

“Amongst the changes of the past year, that of the employment of women in the Royal Observatory at Greenwich has awakened a more widespread interest than at first sight appears to be justified, either by the social or the industrial importance of the movement.

The profession of astronomy is limited for men, and must necessarily, under the most favourable circumstances, be still more so for women. At the present time there are less than half a dozen women in England who are following astronomy as a profession, and it is improbable that there will ever be employment for more than twenty, either at Greenwich or elsewhere. Women, in as far as they are astronomers, are accumulators of facts rather than propounders of theories. They are busy emulating weather-beaten seamen in feats of vision, trying to acquire the delicate touch of the watchmaker, the fine ear of the organ builder, and the open mind of the student of Nature, In this way they learn the common rudiments of a working education, and become sharers of the popular interests of ordinary life.

Having briefly premised so much – having claimed for women astronomers the common insight gained from work, and the common sympathies that unite all workers – I may now consider, as far as may be, the uncommon elements of their employment – those details which belong to the province of practical astronomy. The work divides itself naturally into two parts: the first is the reduction of observations to a regular form, which is the occupation of the day, and the second is the taking of observations at night. The reductions, with which the women’s department is at present chiefly concerned, are those that relate to time. We get our time from Greenwich, but Greenwich must get it every day, if possible, from the sun and stars. To get it roughly within a few seconds, is easy; but the effort to reach perfection is always a difficult task, and to obtain true time within a hundredth of a second involves much calculation. In this work there is a good deal of monotonous detail to be gone through; similar spaces must be measured over and over again, and the same calculations repeated day after day until they become merely mechanical. But in this, what hardship is there, what difficulty beyond the experience of ordinary workers? We see none; for everywhere all-pervading necessity is upon us – upon women as well as men – to follow the narrow way of patient, self-forgetting effectiveness if we would enter into life.

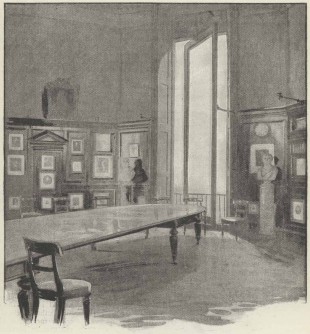

Internal view of the Octagon Room in the late 1890s. The women would have worked at the large table. From The Leisure Hour (1898)

The women at Greenwich, however are not always spinning webs of figures. During the last summer [1890] they were learning photography, and were being prepared for their at present occasional evening occupation – the special work for which they will ultimately be held responsible – that of taking photographs of the stars. To those who delight in connecting the present with the past, the building and surroundings of the Observatory, full as they are of historic associations, offer many and varied attractions. One room in particular, the octagon, is especially interesting, as being the observatory of Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal. It is here that the women do their computations, surrounded by the portraits of illustrious astronomers, who being dead yet speak, telling of the triumphs of industry, ingenuity, and genius, which recognize no distinction of sex, and are no prerogative of a class.”

It would seem from the Report in The Times that their reporter must have been one of the 250 guests who attended the annual visitation. Although much of the report (including the intended provision of sleeping accommodation) derives from the Annual Report, there is no mention (not even the tiniest hint) within the Annual Report itself of there being any women employed at the Observatory. The information about them can only have come from a conversation with the Observatory staff on the day. Although the reporter seemed to believe that the Government sanctioned their employment it is also entirely possible that officials at the Admiralty and the Treasury were not consulted. As things turned out, the designs for the new building underwent considerable alteration and the building was not completed until 1899. Sleeping provision is not thought to have been ultimately provided (see the section on the New Physical Building below).

The Astrographic programme and other photographic work done by the women

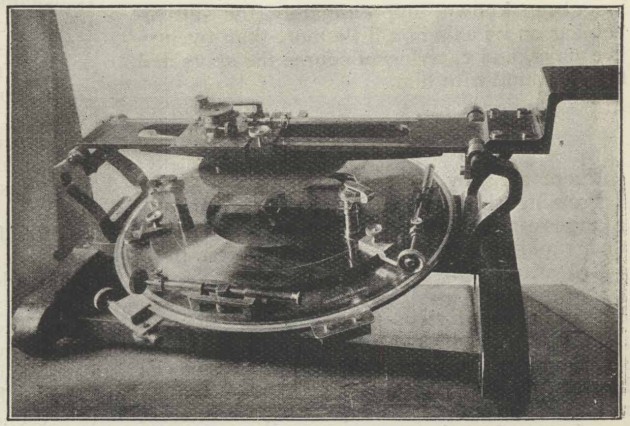

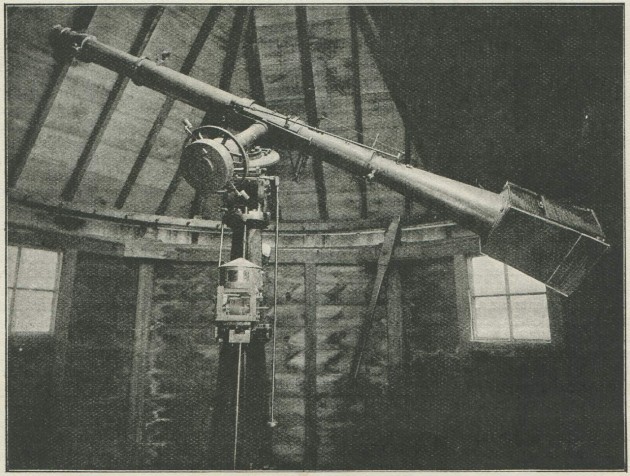

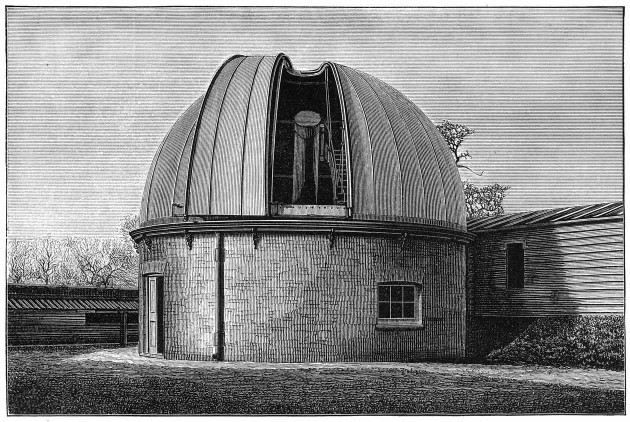

Ordered in 1888 and delivered in March1890 (RGO7/29/106), the 13-inch Astrographic Refractor was one of a number of similar telescopes that were commissioned around that time to take part of an international project (launched in 1887 by Ernest Mouchez, the director of the Paris Observatory) to produce a photographic map of the sky (Carte du Ciel). Made by Sir Howard Grubb of Dublin, the Greenwich instrument consisted of a 13-inch photographic refractor with a focal length of about 11 feet 3 inches (3.43m), firmly connected to a parallel 10-inch visual guiding telescope of the same focal length on a German Equatorial mount. It contributed to both the Carte du Ciel and the Astrographic Catalogue.

The Astrographic Refractor at Greenwich. Photo by the London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company. Known to have been published in Pearson's Magazine in 1896, this higher quality reproduction is taken from the Greenwich Astrographic Catalogue, Volume 1, (HMSO, 1904)

In his series of articles for the Leisure Hour that was published in the late 1890s, Maunder described the role of the observer and the photographs that they were required to take as follows:

‘Rigidly united with the 13-inch refractor, so that the two look like the two barrels of a huge double-barrelled gun, is a second telescope for the use of the observer. In its eye-piece are fixed two pairs of cross spider lines, commonly called wires, and a bright star, as near as possible to the centre of the field to be photographed, is brought to the junction of two wires. Should the star appear to move away from the wire, the observer has but to press one of two buttons on a little plate which he carries in his hand, and which is connected by an electric wire with the driving clock, to bring it back to its, position.

The photographs taken with this instrument are of two kinds. Those for the Great Chart have but a single exposure, but this lasts for forty minutes. Those for the Great Catalogue have three exposures on them, the three images of a star being some 20 seconds of arc apart. These exposures are of six minutes’, three minutes’, and twenty Seconds’ duration, and the last exposure is given as a test, since, if stars of the 9th magnitude are visible with an exposure of twenty seconds, stars of the 11th Magnitude should be visible with three minutes’ exposure.’

Unlike the transit and altazimuth observers whose observations were of a visual and almost instantaneous nature, the astrographic observers had to have the patience and concentration to sit glued to the eyepiece of their guiding telescope for up to 45 minutes for each observation.

A regular programme of taking photographic plates for the catalogue commenced in December 1891 and experimental measure of some of the photographs in 1893. In the meantime, the women were used from time to time to measure some of the solar plates.

Total number of retained photographs taken each year (from Astrographic Catalogue, Vol. I)

1890 |

1891 |

1892 |

1893 |

1894 |

1895 |

||

| 25 | 205 | 487 | 1011 | 694 | 547 |

The introductions to the published observations state that Everett, Rix and Russell all measured solar plates in 1891 and 1892, but only Russell in 1893, 1894 and 1895. The earliest published Measures of position and areas of sun spots and faculae to be made by each of the individuals was as follows: Rix (ER) on 15 February 1891. Everett (AE) on 17 March 1891 and Russell (AR) on 4 September 1892 (suggesting that the information contained in the introduction for 1891 was incorrect). As things turned out, the only woman to measure the astrographic plates from which published results were obtained was Everett. She was involved in measuring them from October 1894 to July 1895.

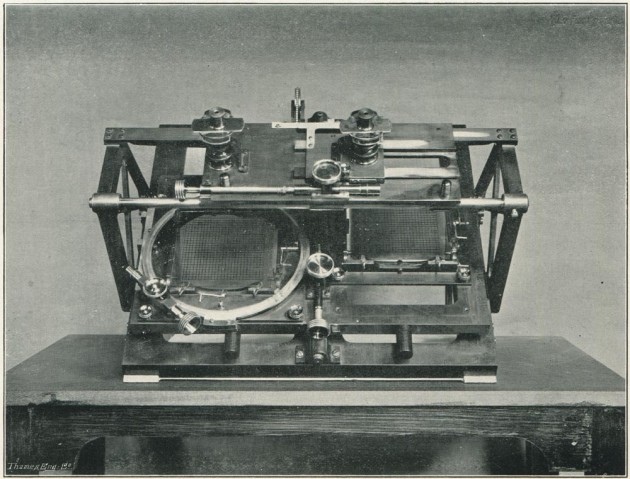

The Solar Micrometer for measuring the size and positions of sunspots on the photographic plates. Photo by E Walter Maunder. From The Leisure Hour (1898) p.376

The Duplex Micrometer (by Troughton & Simms) for measuring the positions of the stars on the photographic plates. It was brought into use in January 1895. Photo by Thames Engineering Ltd. from the Greenwich Astrographic Catalogue, Volume 1, (HMSO, 1904)

At the start of each of the introductions to the volumes of Greenwich Observations, Christie outlined what the responsibilities of the various Assistants had been during the year in question. The following information has been extracted from the volumes for 1893, 1894 and 1895 and slightly re-ordered. The entries are highly unusual in that they also include the names of two of the Computers, namely Everett and Russell. The information provided by Christie gives no insight into whether either Everett or Russell took any of the photographs with the photoheliographs (neither of them is recorded as having an observing certificate for those instruments).

1893:

Mr Criswick superintended the Astrographic observations and reductions. Photographs with the Astrographic equatorial were generally taken by Mr. Criswick, Miss Everett, Miss Russell, or one of the senior Computers.

The measurement of the solar photographs and the superintendence of the reductions connected with them were entrusted to Mr. Maunder. Photographs of the Sun with the Thompson of Dallmeyer photoheliographs were taken by Mr. Maunder or by one of the Computers under his direction.

1894

Mr Criswick superintended the Astrographic observations and reductions. Photographs with the Astrographic equatorial were generally taken by Mr. Criswick, Miss Everett, Miss Russell, or one of the senior Computers.

The measurement of the solar photographs and the superintendence of the reductions connected with them were entrusted to Mr. Maunder. Photographs of the Sun with the Thompson of Dallmeyer photoheliographs were taken by Mr. Maunder or by one of the Computers under his direction.

Observations with the 28-inch refractor were made by Mr. Maunder and Mr. Lewis.

1895

Mr Criswick superintended the Astrographic observations and reductions. Photographs with the Astrographic equatorial were generally taken by Mr. Criswick, Mr. Hollis, Miss Everett, Miss Russell, or one of the senior Computers.

The measurement of the solar photographs and the superintendence of the reductions connected with them were entrusted to Mr. Maunder. Photographs of the Sun with the Thompson of Dallmeyer photoheliographs were taken by Mr. Maunder or by one of the Computers under his direction.

Observations with the 28-inch refractor were made by Mr. Maunder and Mr. Lewis.

An examination of the published volumes definitively shows that none of the women took any of the published transit observations in the year 1890, nor in 1891, 1892, 1893, 1894 or 1895.

Published one-off and ocassional observations with other instruments

Everett is recorded as having made 4 observations of Comet b 1893 with the Sheepshanks Equatorial on 16 & 22 July 1893, (seemingly under the direct supervision of Crommelin and Hollis), but did not make any observations of double stars, though she did do an analysis of the binary Iota Leonis which was published in MNRAS, having been communicated on her behalf by Thomas Lewis.

Kidwell (1984) reports that in 1892 both Everett and Russell observed the opposition of Mars with the ‘12.8 inch and 10-inch telescopes’. The 10-inch telescope is presumed to be the sighting telescope of the Astrographic. A further reference to the same observations can be found in Memoirs of the British Astronomical Association, vol.36, p.88 (1947), which seems to state that they also both observed the same event in 1894, but this time, with the new 28-inch Refractor.

Everett seems to have had a particularly enquiring mind, since as well as making the couple of observations with the Sheepshanks Equatorial mentioned above, she also seems to have taken it upon herself to become familiar with the operation of the transit circle. Following what appears to have been an unauthorised use of the instrument and submission of the results to Turner, he wrote what was possibly a testimonial (dated 8 May 1893). It stated:

‘Miss Alice Everett has submitted to me a number of observations of R.A. & N.P.D made (and reduced) by her with the Greenwich Transit Circle. If these had been submitted by a Computer who had obtained permission to qualify for a certificate for the transit circle, I would have remarked that they were not submitted quite in the usual form, and that several discrepancies were left which might have been corrected. That at the same time it was more satisfactory to have observations submitted independently of their accordance, as this was evidence that they had not been carefully selected and after referring the reductions back for correction, should have signed the certificate. ...’ (RGO7/140/144)

Additional information about Everett and Russell from their testimonials

Christie only appears to have written testimonials for Everett and Russell. He wrote two for Everett; the first was in November 1892 when she applied for a job at the Dunsink Observatory. The second was in 1895 after she had handed in her notice. The first was based on a sheet of information dated 14 November 1892 which was written by Everett herself. The second was based on information dated 27 June 1895 which was supplied by Chriswick (RGO7/138).

As well as confirming the information in the sections above, Everett indicates that in her leisure time she had also ‘observed occultations & phenomena of Jupiter’s satellites, and also practised hundreds of artificial occultatations’ as well as taking a number ‘of eye-and-ear transits with a 3-inch telescope’.

She also states that she had frequently been on duty for taking the daily solar photographs and did a regular night duty with the Astrographic Telescope with the ‘watch sometimes extending to 7 hours duration’. She also mentions that that the work in the Astrographic department ‘which, though increasing,’ took up comparatively little of her time (at that point) and that as a result she had shared in the computations generally and reduced observations for other departments which included originally transits (as mentioned above), but also more recently those of zenith distance.

The photoheliograph as configured between 1890 and 1895. The new secondary magnifier (right) was added on 2 April 1884. Photo by E Walter Maunder. From The Leisure Hour (1898) p.376

Criswick’s statement about Everett is interesting as it re-writes the early history of the Astrographic Project. It starts by saying that Everett ‘was engaged on the meridian transit work till the middle of June 1891, and was then transferred to the Astrographic Depart[ment] ...’. What he should have said, was that she was engaged to work in the Astrographic Department but was largely deployed on meridian transit work until June 1891 when the initial commissioning of the Astrographic Telescope was completed. Criswick also confirms that from the beginning of 1892, Everett was almost exclusively employed on Astrographic work. Interestingly he ends his statement by specifically saying that she was ‘Qualified for [the] Transit Circle and Sheepshank Equatorial observations’. It’s still not clear though if she gained observing certificates for those instruments. One suspects not. It was probably Criswick’s inadvertent re-writing of the project’s early history together with the sparsity of information about Clemes and Furniss in the files, that has caused later historians to misunderstand the true nature of Christie’s ‘Experiment’.

In May 1897, Christie wrote a short testimonial for Russell (by then Mrs Maunder) in support of a grant application she had made to her old College at Cambridge. The unsigned and undated handwritten notes (RGO7/138) on which this appears to have been based state that she observed with the Astrographic Telescope until 5 July 1895 (the day Everett left) and that the preliminary measures and computations of the Astrographic work were to a large extent made by her. It also states that she ‘frequently took Sun pictures’ with the Thompson and Dallmeyer Photoheliographs and that from July 1894 she was entirely engaged on heliographic work and that she was exceedingly had-working and conscientious.

In her notes Everett makes reference to the fact that she is very strong (something she must have felt strongly about given that Rix had had to resign because of her health), but also feels the need to spell out that she should not be barred from the Dunsink post on the grounds of her gender, writing: ‘Miss Russell and I seem to work along quite naturally in the midst of them [the men] here. Of course there are two of us, but we are not always present together’. Once Everett had gone however, it was clearly deemed unwise for Russell to continue with night shifts as an observer on the Astrographic Telescope.

An earlier offer to Agnes Clerke

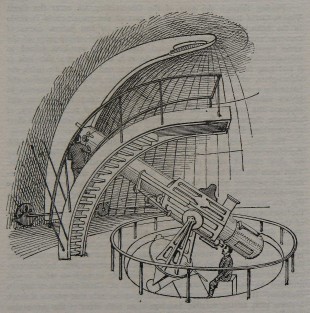

The Lassell Telescope in its dome at Greenwich. Sketched from life on 27 January 1888 (RGO7/29) and originally published by the Pall Mall Gazette on 30 January 1888. This copy is reproduced from Cudworth's: Life and Correspondence of Abraham Sharp (London, 1889)

On the second page of the letter, she wrote: ‘I was offered last week a small appointment in the Royal Observatory and refused it’ she then went on to explain how the offer came about and why she had turned it down. The letter continued.

‘The plan was first mooted in the spring, but more or less confidentially …It’s great attraction for me then consisted in the suggestion that I might have the exclusive use of the Lassell reflector for observing according to any plan I fancied’.

She then expressed her disappointment that ‘when the formal proposal came it included no express arrangements for observing’ The post on offer was a ‘supernumerary computership’, at eight pounds a month. She was also told that Rix was also being engaged. What she didn’t know, was that no sooner had the initial suggestion been aired (possibly by Turner), than serious plans began to evolve for redeveloping the whole of the south end of the Observatory site where the telescope was located. Those plans culminated in the building of the New Physical Observatory with the Lassell Dome relocated to the top of its central tower. As well as not being aware of the changed plans for the telescope, Clerke was probably not aware that in its current location it had a very poor horizon, particularly to the south where the nearby trees severely interfered with its effective use.

The Lassell 2-foot Reflector in the Lassell Dome at Greenwich. It was dismounted in 1892 and replaced with the 12.8-inch Merz Refractor. There are no know images of the Refractor in the dome. From: A Handbook of Descriptive and Practical Astronomy, Volume 2, Fourth Edition (London 1890) by George F Chambers

Taking what Clerke (who didn’t attend a University Ladies’ College) wrote at face value, it would appear that Rix was the first of the four Cambridge women to be offered and to accept a post at the Observatory. Given that Clemes (who graduated a year before Turner and possibly knew him from that time) was about the same age and paid at the same rate that Clerke had been offered, it seems likely that Christie envisaged her as a suitable substitute. The question therefore arises how and when the channel of communication was opened up between Christie and the women he ended up taking on.

Did the idea of appointing a team of women to run the Astrographic programme evolve out of the earlier offer to Agnes Clerke, or was it in fact a largely or entirely separate development, but one, which once formulated, where Christie felt obliged, as a matter of courtesy, to offer a leading role to Clerke? On balance, the weight of evidence (detailed below), seems to point towards the second scenario.

In a later letter to Gill dated 1 June 1890, Clerke was to write somewhat scathingly of the women Christie had taken on:

‘I hear they work very well, but take more coaching than men, because they want to understand more. I should think no educated woman would accept such a post, with such a minute salary, three pounds a month for the inferiors, unless with a view to training for something higher; and getting into a mechanical routine would be fatal to that end’. (RGO15/126/183)

Who she had got her information from is not stated, but as can be seen from the table towards the top of the page she was ill informed about the salaries that the women received.

Women and the Astrographic units in other observatories

Christie was not the only observatory director to take on women specifically to measure the astrographic plates, but he may well have been the first and he may have jumped the gun for his own political ends. The idea of employing women to measure the plates had been floated by Mouchez at the conference of the International Committee of the Carte du Ceil that Christie had attended in Paris in September 1889. As Charlotte Biggs explains, in her paper Photography and the labour history of astrometry: The Carte du Ciel, Mouchez envisaged the creation of ‘a central bureau of measurements, publication and distribution of the photographs and documents pertaining to the Carte du Ciel’, believing that it could be achieved at a reasonable cost, ‘if women were employed for the purpose, as had been done successfully by Bouquet de la Grye for the analysis of Transit of Venus plates, and Gould in the United States.’ Although the plan for a central bureau was not adopted, many of the participating institutions did choose to give the task of measuring their photographic plates to women.In her paper The work of women in astronomy (published in 1899), Dr. Dorothea Klumpke states that no less than seven of the eighteen observatories participating in the Cart du Ceil had women employed to measure them. They were: Paris, Cape of Good Hope, Helsingfors, Toulouse, Potsdam, Greenwich and Oxford. Also on the list, should have been the Melbourne observatory which by 1898 also had a woman working for it. The plates at Paris were measured by a team of four women under the direction of Klumpke herself in her capacity as the first Director of the micrometric service which had been established by Mouchez in February 1892 at the Bureau of Measurements.

Why Cambridge women and not others?

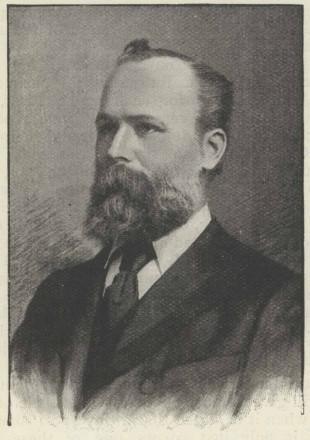

Anne Clough, Mistress of Newnham and President of the Association of Women Teachers. Albumen cabinet card by an unknown photographer, 1880–1892. � National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence (see below)

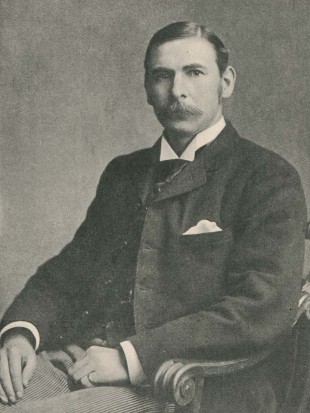

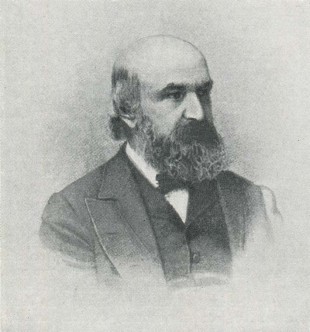

John Couch Adams. From a lithograph engraved by GJ Stodard from a photograph by JE Mayall and originally published in Nature on 14 October 1886 and later in Hutchinson's Splendour of the Heavens (1923)

Although, in February 1890, Christie’s scheme was clearly open to women from any University Ladies’ College and was being promoted by Herbert Rix (Assistant Secretary at the Royal Society), Miss Dorothea Beale (who was in the process of setting up St Hilda’s at Oxford and was Headmistress of Cheltenham Ladies College), Miss Constance Elder (who had attended Newnham and was Secretary of the Association of Women Teachers whose president was Miss Anne Clough, the Mistress of Newnham) and Avril Heyman Johnson (Mrs Arthur Johnson, Secretary of The Association for the Education of Women in Oxford), the appointment of the four Cambridge women was largely settled before applications were received from further afield. That the Cambridge applicants appear to have had a head start, may have been a coincidence, but may also be because the idea of employing Cambridge women may have come from a Cambridge man, and possibly from one of the Visitors either at the 1889 Visitation or at meeting of one of the societies later that year.

At their meeting in June 1889, the Board of Visitors are known to have discussed the Observatory’s staffing problems. Unfortunately, there is no record of what was said, only of the two resolutions that were passed (ADM190/6). The first, proposed by James Whitbread Lee Glaisher (son of Airy’s Assistant James Glaisher) and seconded by John Couch Adams, was for the appointment of a Deputy Chief Assistant. The second, proposed by Glaisher and seconded by the Earl of Rosse was for the appointment of an additional First Class Assistant. Different members of the Board are known to have had very different views on the education of women. The first edition of the Handbook of courses open to women in British, continental and Canadian universities was published in 1896. It tells us that by the academic year 1895–96 just 2% of Cambridge lecturers still closed their lectures to women. Amongst those five individuals were Sir George Stokes, who was Chairman of the Board from 1886–90, and Glaisher. On the other hand, Adams was on the Council of Newnham College and had been since 1880. He had also successfully employed two women Computers at the Cambridge Observatory (a Miss Hardy who worked there from 1876 until 1881 and Anne Walker who had been taken on in 1882 and was effectively a third assistant). Also on the Board was Arthur Cayley, who had been President of Newnham College since 1880 and the Sadleirian Professor of Pure Mathematics since 1863. It is possible that either Cayley or Adams suggested to Christie or Turner, that they could plug the staffing gap by employing women mathematicians from Cambridge as Computers. Interestingly none of Christie’s Reports to the Visitors ever mentioned the fact that women had been employed.

Looking now specifically at the four individuals who were initially appointed: Edith Rix was the cousin of Herbert Rix and Isabella Clemes was treasurer of the Association of Women Teachers in 1891 and may well have held this position in the preceding year(s). It could have been these connections that gave them a head start over the other potential candidates. Of Harriet Furniss’s connections, nothing is known.

Alice Everett, on the other hand, was very well connected though her father, who since 1867, had been Professor of Natural Philosophy at Queen’s College, Belfast and a fellow of the Royal Society (of London) since 1879. Before she was born, he had been Professor of Mathematics at King’s College, Nova Scotia, where he had established an observatory and at the time of her birth, he was assistant to the mathematics professor at Glasgow, where he had worked for a time in the laboratory of William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin). It was Thomson who sponsored Everett for fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1863 and it was Thomson who was headed the list of the fourteen proposers for his fellowship of the Royal Society (of London) (click here to view his nomination form). Amongst his other proposers there were three who were on the Observatory’s Board of Vistors in the late 18880s: Airy, De La Rue and Clifton. It was also Thomson who in 1890, replaced Stokes, both as President of the Royal Society (of London) and also as Chairman of the Board of Visitors. It has to be said however, that Thomson’s involvement with the Observatory did not begin until after the four women had taken up their positions. When asked in 1893 in an interview for The Sketch about how she had acquired her position, Everett replied: ‘That is a long story’ and went on to say:

‘The question of employing women at the Royal Observatory arose when the new photographic section was started, and Mrs. Huggins, who, like her distinguished husband, has earned a world-wide reputation as an astronomer, interested herself, I believe, in the matter. The first I heard of it was when the Observatory authorities wrote to ask if I would come.’

Regrettably (as already stated), there is no record of the correspondence in the Observatory files. William Huggins, on the other hand, had been a member of the Board of Visitors since 1871 and both he and his wife Margaret were good friends with Agnes Clerke. Despite the fact that the first mention in The Times of women being invited to a visitation does not occur until 1890, it is quite possible that Margaret was a regular guest at the annual visitations each June (RGO7/14, which has not yet been examined, might verify this). As to who it was that suggested Everett as a suitable candidate, we are, alas, none the wiser.

Pay

Although better educated than most of the Observatory’s Assistants the pay and conditions of the Lady Computers were broadly the same as those of the existing Boy Computers who were typically paid between £3 and £8 a month. The table below has been compiled from information in RGO7/266 and RGO7/133 and shows the actual salaries of the Boy Computers who were in employment on 1 July 1888.

Monthly

|

Name(s) |

Length of service

|

||

| £8 | Power | 12y + break in service | ||

| £5.15s | Pead Dolman |

10y 4m (age c.25) 6y 2m |

||

| £5.10s | McClellan* | 8y 9m | ||

| £5 | Woodgate Fisher Robinson |

5y 2m 4y 9m 5y 2m |

||

| £4.5s | Wise Finch* |

3y 2m 3y 5m |

||

| £4 | Pilkington Barrow |

2y 4m 2y 1 m |

||

| £3.15s | Hope* Letchford* |

3y 2m 2y 11m |

||

| £3.5s | Cochrane | 0y 11 m | ||

| *Mag & Met Computer |

A letter dated 6 February 1890 from Christie to Dorothea Beale (RGO7/140/10), gives an idea of his initial thinking on the salaries he was prepared to pay:

‘For a lady with her [Miss Dymond’s] qualifications I would propose £6 a month as the initial salary with a prospect of rising gradually to £10 a month or thereabouts. The salary is, I know, small but it may be supplemented by extra payment for observing out of office hours, which might add £20 or £30 a year and if the new departure turns out as successful as I hope, I may be able to get more funds for lady computers.’

With the letter, he enclosed a copy of the Regulations for boy Computers (more on these below) stating ‘to which (for official reasons) it is desirable to assimilate those for ladies at any rate at the start’.

By the time it came to replacing those who had left, the salary on offer was much reduced. When Russell first wrote to Christie in January 1891 expressing an interest in the post that Everett had just told her was about to be vacated by Furniss, she did so in the expectation that the salary would be £6 a month as that is what Everett had been paid (she was also ranked marginally higher than Everett in the Cambridge Tripos). When an offer finally came in July, the pay on offer was only £4 a month. When she queried this (RGO7/140/73) she was essentially told to take it of leave it as the salary on offer was dictated by the Observatory’s own finances.

Later that year, while attempting to recruit a replacement for Clemes, Turner said in a letter to Constance Elder, to whom he was writing on 22 December for help in the recruitment process (RGO7/140/16):

‘The work would appear to be more particularly suitable for those enthusiastic about science than for those whom salary is a consideration of the first importance, We now know a little more clearly what the observatory funds can afford and the Astronomer Royal is prepared to offer £4 a month to begin with, to be increased to £5 as soon as efficiency in the use of the Photographic Equatorial is acquired.’

Despite also writing to all the promising candidates who had been turned down in early 1890, the Observatory was unable to find a candidate who was prepared to accept the money on offer. As a result, Russell turned out to be the last of the Lady Computers to be recruited.

A comparison of what the women earned with the cost of putting them through University makes interesting reading. According to the 1896 edition of the Handbook of courses open to women in British, continental and Canadian universities, fees at Girton for board, lodging and tuition were £35 a term, whilst those at Newnham varied from 25 to 32 guineas (£26.5s to £33.12s).

Working hours and holidays

The 1888 version of Form 134 ‘Regulations for Supernumerary Computers’ sets out the working hours as follows:

‘The hours of attendance are from 9 a.m. to 4.30 p.m., one hour being allowed for lunch (on Saturday 9 a.m. to 2 p.m., with not allowance for lunch), and the strictest punctuality will be enforced.’

‘Holidays not exceeding 24 days in the year will be granted at the discretion of the Astronomer Royal.’

In practice, the women worked a variation of those hours because of their additional observing duties. The actual hours they were required to serve was spelt out by Turner wrote in a letter he wrote to a job applicant (Constance Marks) on 21 December 1891 (RGO7/140/27).

‘The hours are 9–1 every week day; and 2 to 4½ on 3 afternoons a week; with observing on 3 nights, the length of a night’s work depending of course on the weather, but not exceeding 3 to 4 hours.’

Fixed term or open ended contacts?

In a letter written to Christie on 7 March 1892 announcing Rix’s resignation, her mother wrote: ‘She, & we, are more sorry than we can say, that she is forced to give up so honourable & interesting a position; at least under three years, ...’ (RGO7/140/90). This has been interpreted by Brück to mean that her appointment was for a fixed period of three years in the first instance. It is not known if such a time limit applied to Clemes, Furniss and Everett. Clemes and Furniss both resigned long before three years had passed. Everett however remained at the Observatory for over five years. There is no correspondence known that suggests that her contact was ever extended once an initial three years were up. Nor is there any evidence to suggest that Russell was employed on anything other than an open ended contract.

Segregation from the Boy Computers

The arrival of the four women in 1890 must have come as a shock to the other Observatory staff. Given that they were paid about the same as the boys, but better qualified than most of the men, it would be surprising if their arrival at the Observatory wasn’t seen as a threat by at least some of them. As well as their gender, the strong regional accents of the women would have made them stand out from the locally recruited boys. Furniss was from Cornwall, as was Clemes who was largely brought up in Yorkshire, Everett was from Glasgow, but brought up in Ireland and Rix was from Beccles on the Suffolk / Norfolk border.

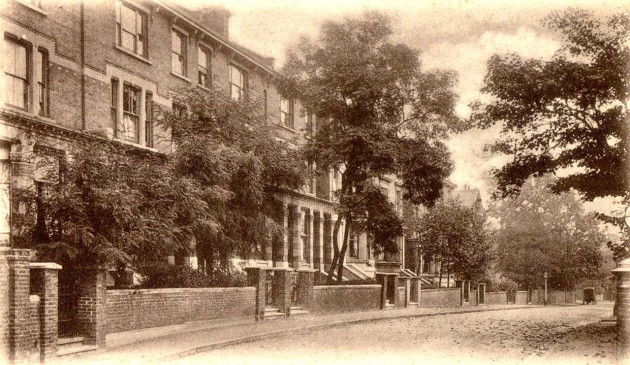

It’s clear from the article in The Churchman (above), that the women (at least to start with) did all their computations in the Octagon Room, which had been brought back into temporary use for this purpose between the autumn of 1887 and the spring of 1888 while the existing computing rooms were being extended. In his 1890 Report to the Board of Visitors, Christie made the somewhat mysterious comment that the room had been ‘assigned as a private room to the Computers’. It would appear that it was only the team of women who were assigned to the Octagon Room at this time. Rather than being a deliberate attempt to segregate them from the men, this may have been simply a practical arrangement as the Octagon Room was probably the only place in the Observatory where, at that time, four desk spaces could be provided for the new department. Given that the women would also have needed toilet facilities, it is possible that ones more suitable for their use would have been closer to hand. Clearly anything practical to do with the use of the Astrographic telescope would have taken place in the photographic dark-rooms attached to the newly extended main computing room at the west end of what today is usually referred to as the Meridian Building, or in the telescope dome above them. It is not known at present where the plate measuring machines were located at that time. Since both the telescope and the plate measuring machines were used by the men, the women were not segregated for the whole of their working week.

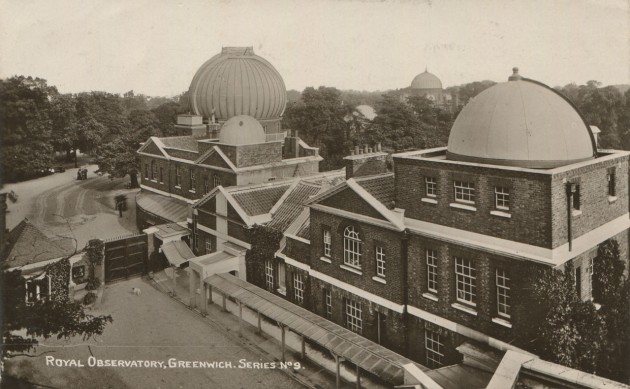

Building building everwhere!

During the whole time that the women were at the Observatory, building work was taking place somewhere or other on the site. The various works and their duration are listed below.:

| 1890 | Porter’s Lodge/Gate House (Courtyard) |

|

| 1891 | Transit Pavilion (Courtyard) |

|

| 1891–99 | New Physical Building (South Building) | |

| 1893–94 | Construction of the Onion Dome for the Great Equatorial (28-inch) Telescope |

|

| 1894–95 | Major repairs to Astrographic Dome after the shutter was blown off |

|

| 1894–96 | Altazimuth Pavilion |

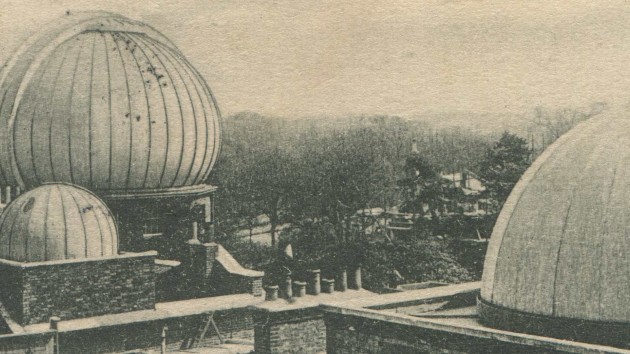

In this earlier view, from 1895, the dome of the Astrographic Telescope is once again on the right. Amongst the trees to its left, the Altazimuth Pavilion is under construction. Photo by York & Son. Detail from a postcard published anonymously

Although the building activity may have added a sense of excitement for the women at the start, the never ending works, with their accompanying noise and dust must have been a serious irritation and distraction at times.

Disasters in the dome

The Journal kept by the Chief Assistant (RGO7/29) shows that 1894 was an eventful year for the Astrographic Telescope. The year got off to a bad start when in the evening of the 2 January: severe weather with snow set in and the observer (unnamed, but one or more of at least five possible people including Russell and Everett) left the dome open all night. By the following morning, the telescope and the inside of the dome were covered in snow which fortunately had not melted and was presumably shovelled out.

The second disaster was much more serious and occurred at the end of the year on 22 December. At 11.32 in the morning, the shutter of the dome was ripped off by the wind and fell into the courtyard below, breaking a few tiles and damaging the roof of the covered way by the entrance to the Airy Transit Circle on the way down. The ‘head piece’ fell inside the dome where it just missed one of the boy computers, Charles Davidson, who was at work printing reticules. This incident put the telescope out of action for two months while the dome was repaired. It came back into use on 22 February 1895.

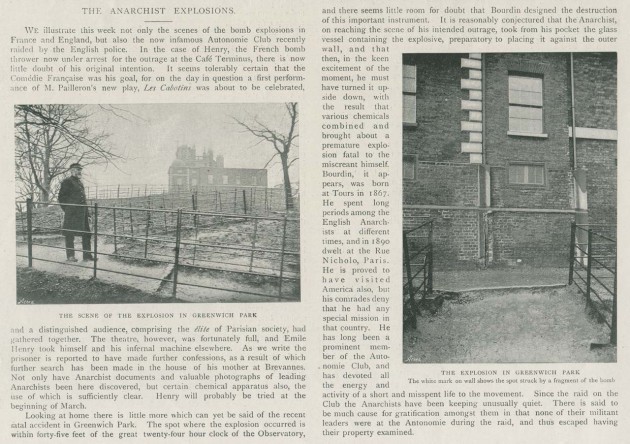

The anarchist bomb – Thursday 15 February 1894

At about 4.45 in the afternoon of Thursday 15 February 1894, a small bomb exploded in Greenwich Park on the zigzag path that (in those days) climbed the slopes to the north-west corner of the Observatory. At the time of the explosion, it was being carried by Martial Bourdin, a French anarchist when lost his hand as a result and subsequently died. It is unclear either what the target was, or why the bomb went off when it did. In the account in the weekly magazine Black and White (below), it is suggested that Bourdin’s aim was to blow up the Gate Clock and that he accidently triggered the bomb too soon as he approached the Observatory. Other reports suggest that the bomb exploded as a result of him tripping on the path.

It seems likely that neither Russell nor Everett were present at Observatory at the time of the explosion. Their working day would either have ended either at 4.30, or at 1.00 if it was one of the days on which they were scheduled to observe. Given that the bomb exploded about half an hour before sunset, they would be unlikely to have reported so early for their evening duty even if it was one of their observing days. If they were in Greenwich at the time, it is likely that they would have heard the explosion. Amongst those staff who were known to be at the Observatory when the bomb exploded were the two Assistants Thackeray and Hollis and the Gate Porter William McManus. The Astronomer Royal himself was not present. He had left shortly beforehand for a long weekend on his yacht which he kept at Sandwich on the Kent coast (RGO7/30).

It is planned to write up this incident more fully at a future date. In the meantime, more information can be read on this blog by Rebekah Higgitt and this blog by Bob Davenport.

The move to the New Physical Building

When the New Physical Building was conceived, it was designed to meet a variety of pressing requirements, including a new computing room for the recently formed Astrographic Branch. Built in stages, the central tower (minus the dome) was completed first, followed by the south wing, which was completed after many delays on 20 April 1894. The Photoheliograph and its hut were mounted on the concrete terrace roof of the south wing for daily observation of the Sun on 26 April. The three floors were initially used as follows. The attic floor was used to house the staff of the Astrographic Branch; the main (middle floor) was used to house the Heliographic and Altazimuth Branches, whilst the lower floor was fitted up as the Mechanics’ workshop, with a gas engine and dynamo for electric lighting.

The New Physical Building in the summer of 1897 before the east wing was completed. The south wing where the Astrographic and Heliographic Departments were relocated is on the left. The hut on the roof housed the photoheliograph. Photograph reproduced by permission of the Greenwich Heritage Centre (see below). A copy of the photo was published in the 17 July 1897 edition of the Illustrated London News

Lodgings

Little information is available as to where the five women lived. The list below shows their known addresses on specific dates.

| Clemes | 1890, Dec 31*** | 1 Highbury Terrace, N [5]. |

|

| 1891, Dec 26+ | 19 Somerset Terrace, Tavistock Square, W.C. | ||

| Furniss | 1890, Dec 30* | 9 Crooms Hill | |

| Rix | 1890, Dec 30**** | 9 Crooms Hill | |

| 1892, Jun 30*** | Crooms Hill | ||

| Everett | 1890, Dec 31*** | 8 Gloucester Place (now 8 Gloucester Circus) | |

| 1891, Apr 5***** | 8 Gloucester Place |

||

| 1892, Feb 12** | 8 Gloucester Place |

||

| 1892, Jun 30*** | 9 Crooms Hill | ||

| 1893, Jun 30*** | 18 The Circus (now 38 Gloucester Circus) | ||

| 1894, Jun 30*** | 18 The Circus |

||

| Russell | 1892, Feb 12** | 16 The Circus (now 36 Gloucester Circus) | |

| 1894, Jun 30*** | 16 The Circus |

||

| 1895, Sep 30++ | 16 The Circus |

* Resignation letter (RGO7/140/96) **Nomination form for fellowship of Royal Astronomical Society

*** List of Members of the British Astronomical Association (1890, 1892, 1893, 1894)

**** Inferred from letter from Mrs Rix to Christie (RGO7/140/85)

***** Census + Letterhead University Association of Women Teachers (RGO7/23)

++ Resignation letter (RGO7/138)

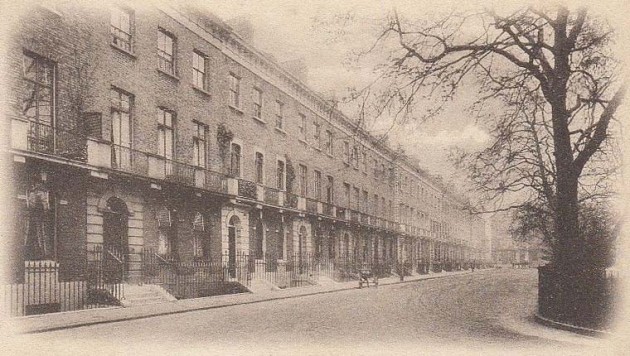

Looking westwards along The Circus. Number 18 is the first house from the left not to have arched windows. Number 16 is two doors to its right. Gloucester Place was on the other side of the circus, with number 8 being more of less opposite. From postcard No. 630 published by Perkins Son & Venimore (PS&V) in 1904

Looking Eastwards along Gloucester Place towards Greenwich Park. Number eight where Everett lived for a while is the fourth house from the far end of the terrace on the left. All the houses to its left have since been demolished. From postcard No. 654 published by Perkins Son & Venimore (PS&V) in 1904

All the houses in the above list (except those where Clemes lived) were located roughly 600m from the Observatory and within just a few minutes walk of each other close to the north west corner of the Park with easy access to either of Greenwich’s two stations (Greenwich and the now demolished Greenwich Park). By contrast, most of the Assistants lived on higher ground on the opposite side of the Park. Between 1885 and 1888, three of them, Maunder, Hollis and Lewis moved into newly built houses in Ulundi Road, staying until 1895, 1896 and 1917 respectively. They were joined in 1893 by Crommelin who moved away in 1894, only to return in 1899.

Regulations for the appointment of Supernumerary Computers

By 1858, candidates for the post of Supernumerary Computer were generally appointed by competitive examination amongst 13 and 14 year olds from the local schools. Although, at that time, there was no upper age limit to those who might be employed, the poor wages, temporary nature of the posts and a general lack of vacant posts at the assistant level, meant that most moved on relatively quickly. Examination for promotion to and within the Assistant Grade (for trial of competency) began for the first time after the fourth assistant Hugh Breen handed in his resignation in November 1858.

Candidates hoping to be employed as Supernumerary Computers needed to have a certain level of literacy and numeracy skills. In 1857, the requirements were listed by Airy on what was known as Form 134 (RGO7/6), which was presumably sent out to prospective candidates. By 1888, Form 134 had evolved into a formal set of ‘Regulations for Supernumerary Computers’ (RGO7/6). As well as listing the subjects of examination (‘Writing from dictation, to test hand-writing, spelling, and punctuation. Arithmetic, including extraction of square roots, and use of logarithms. Algebra, to quadratic equations inclusive.’), it had six main clauses. The first stated that candidates for the examination needed to be between the ages of 14 and 18 years, and that ‘every Computer will be liable to be discharged at the age of 23 unless special circumstances should make it desirable to retain his services’. The second stated that starting pay was normally £3 a month and that increments were granted ‘at the discretion of the Astronomer Royal’. The third gave details about the notice period. The fourth listed the hours of attendance. The fifth gave details of annual leave and the sixth stated that Computers were required to live within about a mile of the Observatory. The key changes from 1858 were the newly specified age limits and the requirement to live within a stated distance of the Observatory. The provision for the discharge of Computers at the age of 23 was introduced by Christie on 29 January 1883 and come into effect on 1 January 1884 (RGO7/133).

Interstingly, the 1888 Regulations for Supernumerary Computers did not state that only men were eligible to apply for a post. When an enquiry about the ‘Lady Computer’ posts was made of the Astronomer Royal in February 1892 by a Mrs Allen (a local parent) on behalf of her 15 year old daughter, she received a reply from Turner on his behalf which enclosed details of the competitive examinations and stated ‘that he was directed to enquire’ if she (the daughter) would be able to pass them (RGO7/140/100). This would seem to imply that at this point in time (if only briefly), Christie was not only prepared to take highly educated women onto the staff, but that he was also prepared to consider employing teenage girls on the same basis as teenage boys. As things turned out however, neither Miss Allen nor any other schoolgirl was ever taken on as a Computer by him. Nor are any known to have sat the exams.

When Form 134 was republished in August 1911, although there were several minor changes from those of 1888, the main change was the lowering of the age of discharge (unless special circumstances applied) from 23 to 21. (RGO7/140)

Regulations for the appointment of Second Class Assistants and the eligiblility of women to apply

It has long been held by historians, that women were not eligible to apply for the Assistant posts at the Observatory. Although none were appointed and none seem to have applied, an examination of the evidence suggests that they were not necessarily barred by the regulations.

Ignoring for a moment the question of eligibility on the grounds of gender, in 1890, Christie would have been unable to appoint the four women he took on as Assistants, firstly because there were no vacancies and the number of posts was strictly regulated by the Government and secondly because such posts had to be filled by open competition and could no longer be filled at the whim of the Astronomer Royal as they had been for many years under Airy, his predecessor. Christie did however have complete control over the hiring and firing of the Computers and was in a position to pay the women from this budget, but in order to do this, he had to waive:

1. The requirement for the women to take the entry exams.

2. The age limits in force in 1888.

3. His stipulations on the normal starting salary.

4. Any real element of competition (as the women, most certainly Russell, seem to have been appointed on a first come first served basis)

The splitting of the Assistant grade into First and Second Class Assistant in 1872 coincided with the introduction of open competitive examinations administered by the Civil Service Commissioners. Between 1872 and 1896, a total of eight Second Class Assistant appointments were made.

Exam Date |

Appt. Date |

Name |

Age requirement |

Probation (months) |

|

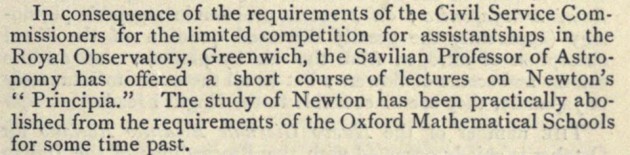

| 1872, Dec 10 | 1873, Jan 17 | Downing | 18–25 | 6 | |

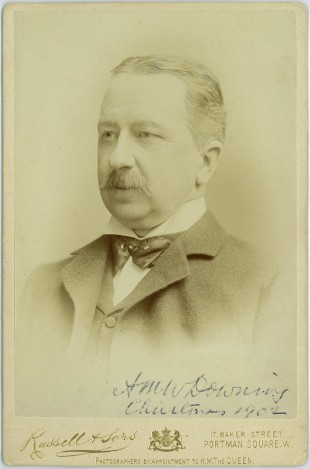

| 1873, Sep 16 | 1873, Nov 6 | Maunder | 18–25 | 6 | |

| 1875, Jan 26 | 1875, Feb 25 | Thackeray | 18–25 | 6 | |

| 1880, Apr 27 | 1881, Jan 24 | Lewis | 18–25 | 6 | |

| 1881, Oct 28 | 1881, Nov 22 | Hollis | 18–25 | 6 | |

| 1891, Mar 23 | 1891, May 11 | Crommelin | 21–30 | 24 | |

| 1891, Dec 28 | 1892, Feb 8 | Bryant | 21–30 | 24 | |

| 1891, Dec 28 | 1892, Feb 12 | Hudson | 21–30 | 24 |

The first five appointments were made under the General Regulations that applied to all Civil Service posts appointed by open competitive examination, together with the Special Regulations that applied specifically to those posts at the Observatory. In 1872, the Special Regulations stipulated that entry to the examination was restricted to people of age 18 to 25 (CSC6/1/69). Therefore if a Computer hadn’t obtained promotion by the age of 26, he would have no prospect of ever being taken on as a permanent member of staff at the Observatory. With vacancies at the Junior Assistant grade being rare and normally only arising when an Assistant died or retired, some Computers would have had virtually no chance of ever gaining promotion, no matter how good they were. The same age limits applied for the next four appointments, the last two of which took place in 1881.

Neither the General or Special Regulations for Downing’s post specifically stated that only men were eligible to apply for a post. In fact, paragraph 2 of the versions of the General Regulations that applied to Downing, Maunder and Thackeray seem to state quite the opposite (RGO6/7, CSC6/1/69 & CSC6/1/138):

‘The examinations will be open, with such exceptions under such conditions as may be laid down, to all natural-born subjects of Her Majesty, being of good health and character.’

Much the same form of words appears at the start of paragraph 3 of the General Regulations that were in force when Lewis and Hollis were appointed (CSC6/2/132 & RGO8/31 & RGO7/8):

‘The examinations are open, under such general restrictions as may be laid down, to all natural-born subjects of Her Majesty, being of the requisite age, health and character.’

When entry to the Assistant level posts by open competitive examination commenced in 1872, the University Women’s Colleges were in an embryonic state and it seems unlikely that any thought was given by the Admiralty or Astronomer Royal to the fact that women might be tempted to apply. Although the General and Special Regulations make frequent use of the word ‘candidate’, the pronoun ‘he’ is also occasionally used in the Special Regulations. The pronoun ‘she’ however is not. Precisely how the wording might have been interpreted had a woman applied is not known.

Click here to view the Special Regulations for the post of Second Class (Junior) Assistant the issued on 29 October 1872. Click here to view the General Regulations as amended on 9 November 1875. Click here for alternative link. Click here to view the Special Regulations for the post of Second Class (Junior) Assistant the issued on 14 December 1874. Click here for alternative link.

After 1881, there were no further appointments until 1891. That appointment was followed by two more in early 1892. Not being satisfied that candidates appointed though open competition always proved to be competent observers, Christie managed to persuade the Commissioners (and presumably the Admiralty) to change the rules. As well as raising the lower age bar to 21 and the upper to 30, instead of making the three appointments by open competition, they were made using a ‘limited competition of nominated candidates’. The exams for the three posts took place on 23 March and 28 December 1891 (CSC6/5/168 & 218).

Under this regime, Christie touted for suitable candidates who might be known to his astronomer friends, who advertised the post on his behalf with the instructions:

‘Candidates are requested to apply without delay to the Astronomer Royal, Royal Observatory, Greenwich, who will require to be satisfied as to their practical acquaintance with astronomy, before nominating them.’ (RGO7/6)

Writing to a potential Candidate on 27 Nov 1891, Turner stated:

‘He [the Astronomer Royal] will be happy to nominate you on receiving a testimonial from some competent person that you are able to take transits & find the time from your observations and observe zenith distances etc: in fact have such elementary practical knowledge of Observatory work as would obviate the necessity for detailed instruction on your appointment here. Should your experience not extend exactly in this direction perhaps a few visits to the Cambridge Observatory might supplement it in the required manner.’ (RGO7/6)

It would be interesting to know what discussions took place between Christie and the women employees when these posts became available. Although Everett mentions them in the interview that she gave to The Sketch in 1893, she provides very little detail:

‘It is doubtful whether women are eligible for the examination, and candidates must be nominated by the Astronomer Royal, who refused to take the responsibility when we applied. Of course, we were new and untried. Things must, I suppose, develop by degrees. We hold a rather non-descript position at present.’

Christie was certainly wary of how the Civil Service Commissioners might regard the employment of women if they applied for an established post at the Observatory. This was explained in a letter dated 15 July from Turner to Lucy Worsfold who had enquired about posts at the Observatory in the summer of 1890.

‘I beg to inform you that 4 ladies are at the present time employed as Computers at this Observatory, these being the only appointments in the hands of the Astronomer Royal, and therefore the only ones in which it is possible to employ ladies without raising the question of their recognition by the Civil Service Commissioners.’ (RGO7/140/63)

Given that Christie was:

a) wary of the Commissioners’ approach to women

b) able to vet and veto potential applicants

c) able to recruit degree level Lady Computers who were willing to do the same

work as a Second Class Assistant for less than half the pay,

he was hardly likely to encourage his Lady Computers to apply for a Second Class Assistant post, nor to provide them with the necessary observing experience on the Transit Circle that was required.

Could the reason that Clemes resigned be linked to the fact that as well as being barred from applying for the vacant post both on account of her age she may also have been blocked by Christie on account of her gender? And was a block on promotion at Greenwich on the grounds of gender the reason why Everett applied (unsuccessfully) for a post at the Dunsink Observatory in Dublin in late 1892

Unequal pay for equal qualifications?

The table below shows the starting salary and qualifications of all the Second Class Assistants, Lady Computers and Chief Assistants appointed between 1872 and 1896. Unlike the Assistant posts, the Lady Computer posts were not pensionable. The ranking given in the Cambridge maths tripos is the overall position amongst all the male students who sat the exams in a particular year. Dyson was head hunted as Chief Assistant, and unlike Crommelin, Bryant and Hudson, did not have to satisfy the Astronomer Royal in advance with his practical skills in astronomy (which at that stage he didn’t have).

Appt. Date |

Name |

Post |

Starting Salary |

Degree |

|

| 1873, Jan 17 | Downing | 2nd Class Assist. | £200 | Trinity College Dublin (BA 1871, MA 1881, Hon PhD 1893) | |

| 1873, Nov 6 | Maunder | 2nd Class Assist. | £200 | University College (1864-7) & King's College London (1872 as an occasional student) | |

| 1875, Feb 25 | Thackeray | 2nd Class Assist. | £200 | n/a | |

| 1881, Jan 24 | Lewis | 2nd Class Assist. | £200 | n/a | |

| 1881, Nov 22 | Hollis | 2nd Class Assist. | £200 | Cambridge, senior optime (ranked 37th, 1880 maths tripos) | |

| 1890, Apr 14 | Clemes | Lady Computer | £96 |

Cambridge, senior optime (1881 maths tripos) |

|

| 1890, Apr 14 | Everett | Lady Computer | £72 |

Cambridge, senior optime (ranked between brackets 43 and 47, 1889 maths tripos). Royal Universitiy of Ireland (BA 1887, MA 1889) |

|

| 1890, Apr 14 | Furniss | Lady Computer | £48 | Cambridge, aegrotat (maths tripos) |

|

| 1890, Apr 14 | Rix | Lady Computer | £48 | Cambridge, studied but did not sit maths tripos | |

| 1891, May 11 | Crommelin | 2nd Class Assist. | £200 | Cambridge, wrangler (ranked 27th, 1886 maths tripos) | |

| 1891, Sep 1 | Russell | Lady Computer | £48 | Cambridge, senior optime (ranked between brackets 41 and 43, 1889 maths tripos) | |

| 1892, Feb 8 | Bryant | 2nd Class Assist. | £200 | Cambridge, wrangler (ranked 21st, 1887 maths tripos) | |

| 1892, Feb 12 | Hudson | 2nd Class Assist. | £200 | Cambridge, wrangler (ranked 17th, 1890 maths tripos) | |

| 1896, Mar 1 | Dyson | Chief Assistant | £500 | Cambridge, wrangler (ranked 2nd, 1890 maths tripos) |

Resignations, replacements and the ending of the ‘experiment’ – the sequence of events