…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

Telescope: 28-inch Refractor (1893)

Ordered in 1885 and brought into use in 1893, the 28-inch Refractor is the largest in the UK and one of the ten largest refractors ever built. Its unusual design meant that it was suitable for both visual and photographic use. Made by Sir Howard Grubb of Dublin, the telescope was a replacement for the smaller 12.8-inch Merz Refractor, on whose mounting it was placed.Confusingly, both the 12.8-inch Merz and the 28-inch Refractor have been, and still are, referred to as the ‘Great Equatorial Telescope’. Similarly, the building in which they were located at Greenwich has been known both as the ‘South-East Dome’ and as the ‘Great Equatorial Building’.

Mothballed in 1939 at the outbreak of war, the 28-inch Refractor remained out of use until 1957. When it came back into service, it was not at Greenwich, but at the Observatory’s new home at Herstmonceux, where it was mounted in Equatorial Dome F. Having later been declared redundant, it was donated to the National Maritime Museum where it was re-mounted in its original location in 1971 (Object ID: AST0932). The telescope remains in the care of the Museum and is one of its most popular exhibits on account of its size and appearance. It is retained in working order and is used for public viewings throughout the year.

Background to the telescope’s acquisition

In 1875, a spectroscopic programme was commenced with the 12.8-inch Merz Refractor. To start with, a spectroscope by Browning was used, but in 1877, this was swapped for a ‘half-prism’ spectroscope designed by William Christie who was then the Observatory’s Chief Assistant. During the day it was used to observe the prominences of the edge of the sun and the spectra of solar spots, in order to obtain records of their frequency and changes. At night it was used for visual determinations of the motions of stars in the line-of-sight by comparing certain lines in their spectra with those of different gases. The spectroscope was used to measure the shifts in the spectral lines from their normal positions as a result of the Doppler Effect – a technique that had been pioneered by William Huggins who had used it in 1868 to determine the line-of-sight velocity of Sirius. The Greenwich programme was carried out mainly by Maunder with some assistance from Christie (who became Astronomer Royal in 1881). The Merz, however, proved too small to allow anything but the brightest stars to be observed. The Lassell Telescope which was acquired by Christie in 1883 was more powerful, but was unsuitable for spectrographic work as its mounting and clock-work were not capable of carrying a heavy spectroscope. Christie therefore set about trying to procure a larger refractor. In 1885, he proposed in his Annual Report to the Board of Visitors that the Merz telescope should be replaced with a larger 28-inch refractor on the same mounting, the main justification being that it was needed to allow the spectrographic work to proceed effectively. At that point, the telescope was intended solely for visual use and was to be housed under the drum dome already in place. The matter was discussed by the Visitors at their meeting on 6 June 1885, where it was explained that the telescope as proposed could be secured at a cost under £4,000. The proposal was unanimously supported by the Visitors who were present, which included Airy. The resolution passed on to the Admiralty ended with the following sentiment which undoubtedly had its origins with Christie, who had done his homework on the matter:

‘This Board would observe that the principal Equatorial Telescope of the Royal Observatory [The 12.8-inch Merz] is very far inferior to those of the chief observatories of Europe and America; and further, that the suitability of the present mounting, for the proposed telescope would effect a saving of £9,000, the cost of mounting and dome’. (ADM190/6/8)

In 1859 in his Report to the Board of Visitors, Airy had stated that the mounting of the Merz telescope was capable of holding a larger telescope and that ‘it might with some inconvenience carry a telescope of above 20 feet focal length; and, if the regions near the pole were given up, it might carry one still larger.’ As well as having an aperture of 28-inches, the proposed new telescope was to have a focal length of 28 feet – the maximum size of both the aperture and the focal length being constrained by the requirement that the telescope should fit onto the existing mounting. Having been approved by the Board, the proposal was subsequently also approved by the Admiralty who wrote to Christie on 1 September 1885 enclosing a letter from the treasury approving the gradual provision during the next three of four years, of the sum of £3600 for the new telescope. (ADM190/6/26).

1886 – from purely visual to a photo-visual design

Although photography had been used in astronomy since the 1840s and at Greenwich for solar work since 1874, it was not seriously used in an attempt to map the stars until the early 1880s, following the introduction of the gelatine dry-plate process in 1876. In the vanguard of this change was David Gill, Her Majesty’s Astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope who had inadvertently kick started the process when an experimental photograph he took of the great comet of 1882 revealed a well defined star field behind it.

In his 1886 Report to the Visitors, Christie announced that the 28-inch telescope was to be ‘available for spectroscopy and photography as well as for eye-observations’ and that Grubb proposed to provide means for readily separating the lenses of the object-glass to ‘such a distance as will give the proper correction for photographic rays’. At the same time, he reported that he was about to order a lens of flint and crown glass for use with the 12.8-inch Merz as a corrector for photographic use. Following the annual meeting of the Board on 5 June, George Stokes, the Chairman, wrote to Christie suggesting that if suitable curvatures were chosen for the surfaces of the 28-inch lens, then rather than just the approximate correction for photographic work that would be secured by simply altering the separation of the flint and crown elements, an exact correction could be obtained provided that at the same time the crown glass element was reversed. It was this novel design for the object-glass that was adopted by Christie and Grubb.

Christie’s underlying motives for equipping the 28-inch with an object-glass suitable for both eye-observation and photographic work rather than just eye-observation as orignally intended, requires further research. The additional cost would have been minimal, though it did come with an increased risk of damaging the lens whilst in use. Christie was much keener than his predecessor in pursuing the emerging science of Astrophysics and not averse to embracing new innovations and technology. He did not however have a terribly good working relationship with Gill and professional rivalry may well have played a part.

A trial version of the object glass

In the late 1880s, the Sheephanks Equatorial was used to trial scaled down versions of the object glasses of the 13-inch Astrographic and the 28-inch refractors. In this role, it was used as a directing telescope. In the case of the 28-inch refractor, trials with a four-inch experimental object glass supplied by Grubb commenced in the summer of 1889. Grubb himself had already carried out trials by this point and as well as subsequently manufacturing the 28-inch object glass, he also marketed scaled down versions in his 1888 trade catalogue.

Delays and a change of plan with the dome

The manufacture of large glass discs free from internal defects was not easy and very few companies were in the market to supply them. On 23 September 1885, Grubb wrote to Christie to inform him that Chance Brothers of Birmingham had agreed to make the glass for the two lenses. In May 1886, Christie was able to report to the Visitors that a flint disc that promised to be a very satisfactory had been made. The manufacture of the crown element proved rather more problematic and the possibility of obtaining a blank crown element from Charles Feil in Paris was explored. Eventually, in October 1888, Chance Brothers were able to supply a pair of what Christie described as ‘very satisfactory glass disks’. By then however Grubb had become exceptionally busy with many other orders to fulfil. They included a number of 13-inch telescopes for the Astrographic Project, including one that had been ordered that August by Christie for Greenwich. As a result, work on the Greenwich 28-inch Refractor was slow to proceed. By May 1890, Grubb was working on the figuring of the lenses by May 1891 the object glass was complete as was most of the rest of the instrument.

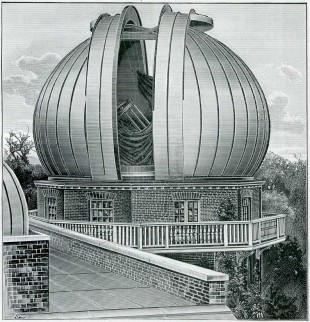

In May 1890, Christie reported difficulties in turning the dome, which on investigation appeared to be largely due to the irregular shape of the cannon balls on which it rolled and to a sagging of the dome curb especially near the shutter opening where it appeared to have broken away from the upright beams that tied it to the structure. To remedy this, Christie proposed substituting properly turned spheres for the cannon balls. He also though it advisable to enlarge the shutter opening. The cannon balls were duly replaced, but although there was some improvement, the dome remained unserviceable. In view of this, Christie designed a new 36-foot onion dome. Wiggleworth and Fred Cooke of T Cooke & Sons of York, made a site visit to Greenwich on 18 March 1891 and agreed to construct the new dome for £850 (RGO7/29). This was sanctioned by the Admiralty and the order placed. Delays arose partly because Cooke & Sons needed to erect a larger workshop to accommodate it and partly because it was of an unusual form. The Merz telescope was dismounted on 23 November 1891.The old cylindrical dome was dismounted in November 1892, and the mounting of the new dome which commenced on 16 December was completed on 25 April 1893.

The 28-inch dome in about 1900. From the Illustrated Catalogue of T. Cooke & Sons (London & York, 1908)

Christie’s description of the telescope

Christie only ever wrote a short description of the telescope. This was published in the introduction to each of the volumes of Greenwich Observations from 1893 to 1908. The text below is from the 1908 volume and bar a few extra words is identical to that published in 1893. The description of the mounting was written up in great detail in Appendix 3 to the 1868 volume of Greenwich Observations and for that reason has been omitted from this transcription.

‘The object-glass of 28 inches clear aperture and 27 ft. 10 in. focal length was made by Sir Howard Grubb from discs supplied by Messrs. Chance, of Birmingham. It is of special form, adapted to photography as well as to eye-observation, on the plan proposed by Sir George Stokes (in a letter to me dated 1886 August 16) of reversing the crown lens to correct for the spherical aberration introduced by the further separation of the lenses necessary for photographic correction. Mechanical means are provided for readily effecting this reversal and separation without risk. It is found by trial that the further separation required for photographic correction is about 3.5 inches, and that the focus is thereby shortened by about 23 inches. When the crown lens is in the position for visual observation, the radii of curvature of the surfaces are:-

| Crown | |||||||

| 1st | surface | 146 | inches | convex | |||

| 2nd | surface | 134 | inches | convex | |||

| Flint | |||||||

| 3rd | surface | 138 | inches | concave | |||

| 4th | surface | 1000 | inches | convex | |||

and the edges of the lenses are separated by 0.4 inch, the minimum focal length being for rays about midway between D and E.

The telescope tube, made of steel and cast-iron by Sir Howard Grubb, is specially adapted to the conditions, being provided with a sliding eye-end arranged for either direct or diagonal view by means of a silver on glass plane reflector, and permitting of observations near the zenith and the pole, when the eye-end is shortened sufficiently by the sliding motion to clear the floor and the inside of the polar frame, The Corbett telescope, of 6½ inches aperture and 8 feet focal length, is mounted on the tube as a finder or guiding telescope. The position and transit micrometers and various eye-pieces supplied for the l2.8-inch Merz refractor, have been adapted to the new 28-inch telescope, and have been fitted with electric illumination of the field and wires. A double-image micrometer is also used.’

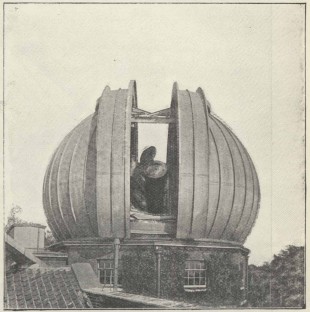

A view showing the hinged waterproof cover at the object glass end of the telescope, which appears to have been removed in the early 1900s. Its large size probably made it vulnerable to wind damage. Photograph by E Walter Maunder. From The Leisure Hour (1898). The photo was later used on the cover of Maunder's book The Royal Observatory Greenwich (London, 1900)

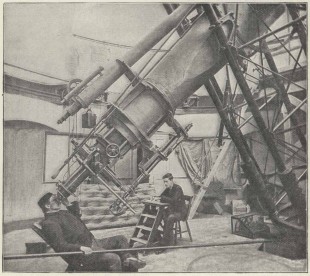

In this early photograph of the telescope, the body of the spectroscope has been removed and a telescope, whose identity is undocumented, slung beneath the 28-inch Refractor. Comparisons with the Corbett guiding telescope imply it has a diameter of about 9 inches, suggesting that it might be the Thompson 9-inch Refractor. This was normally mounted on the Thompson Equatorial, but was also sent on eclipse expeditions. Photo by the London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company. Known to have been published in Pearson's Magazine in 1896, this version is taken from a magic lantern slide.

In 1894/5, ‘a light waterproof cover working on hinge’ worked by means of a cord at the eye end was fitted to the object end of the telescope so that the object glass could be covered and uncovered more easily. In the same year, the clock Dent 2009 was installed in the dome and a mattress provided for making observations near the zenith.

The positions in which the telescope could/can be used are limited by the framework of the polar axis as well as the fact that near the zenith the eyepiece does not clear the floor. In the Catalogue of Double Stars from Observations made at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich with the 28-inch Refractor during the years 1893–1919, Dyson gave a table showing the highest declination that can be reached at different hour angles:

| Hour Angle | Declination | |

| h m | o | |

| 0 0 | 30 | |

| 1 0 | 32 | |

| 1 30 | 36 | |

| 2 0 | 40 | |

| 2 15 | 44 | |

| 2 30 | 50 | |

| 2 45 | 65 |

Reversing the crown glass element

In his description of the telescope, when talking about reversal of the Crown element of the object glass, Christie states without further elaboration that ‘Mechanical means are provided for readily effecting this reversal and separation without risk.’ Given that the crown element weighed 77 pounds, it would be interesting to know exactly how this was done and how many people were needed to do it.

The first trials in photographic mode began on 23 January 1894. It took a while to determine the best distance between the lenses and the exact adjustment of the crown lens for tilt and centering relative to the flint lens. A small number of modifications were made and special contrivances devised to allow for the delicate adjustment required. In June 1894, the telescope was returned to visual mode and a programme of micrometric observations of double stars commenced.

A second photographic trial took place in 1897 when the telescope was used continuously in photographic mode from 12 January - 23 April, except on 17 February, when the object glass was reversed for the day for visual observing. After examining the photographs obtained, Christie declared that the photographic correction was ‘quite successful’. The telescope was used again for photography later in the year on about seven days between 5 August and 23 September. This appears to have been the last occasion that it was so used.

Consigned to visual use

In early 1894, just a few months after the 28-inch Refractor had been brought into use, Sir Henry Thompson arranged for Christie to meet with him at his club and offered to pay for a new photographic refractor for the Observatory. At this point, the 28-inch Refractor was still undergoing testing in visual mode and photographic trials had yet to begin.

Born in 1820, Thompson was an immensely wealthy and successful surgeon who in 1880 had built his own observatory and believed that the future of astronomy lay in photographic work. In 1890/1, with there still being no indication of when the 28-inch Refractor might be up and running at Greenwich, he donated his own 9-inch photographic refractor to the Observatory.

By 1894, clearly exasperated by all the faffing around and believing that without a good photographic instrument Greenwich would be unable to maintain the country’s astronomical pre-eminence he decided to make his offer to Christie. A new telescope, the Thompson 26-inch Refractor was ordered in 1894 and brought into use in 1898. As a result, after the end of 1897, the 28-inch was only ever used visually.

An accident waiting to happen

The Great Equatorial Building and telescope from the west in about 1905. The canvas sail protecting the telescope and observer is clearly visible, but the hinged waterproof cover at the object glass end of the telescope seems to be no longer present. Photo courtesy of Hillary Buckle

The length of the telescope tube relative to the diameter of the dome means that even with the onion dome, the end of the telescope extends beyond the dome envelope when it is being used at low altitudes. Because of this, there is an ever present risk of the end of the telescope colliding with the dome – a risk that is probably increased by the fact that the dome has to be moved manually by the operator to keep the shutter opening in front of the telescope as it tracks its way across the sky. Despite this vulnerability, the author is unaware of any collisions occurring.

The length of the telescope also means that it cannot, in normal use, be swung through the zenith without striking the floor. In order to allow observations to be made at the zenith, the telescope was originally provided with a sliding eye-end arranged for either direct or diagonal view by means of a silver on glass plane reflector. Despite this, disaster struck on 30 April 1901 when the large position micrometer at the eye end accidently struck the floor causing it serious damage.

A problem with wind

The design of the dome’s shutters left not only the observer excessively exposed to the wind, but made the telescope vulnerable to wind-shake. In 1895, with the assistance of the Admiral Superintendent and Staff Captain at Chatham Yard, canvas sails to act as wind-screens were fitted up on the both sides of the shutter opening. The sails, which were completed at the end of February, were each 22 feet high by 8 feet wide, and could be hauled up or down to any required position by tackle specially arranged for the particular conditions prevailing.

Observing programmes at Greenwich 1894–1919

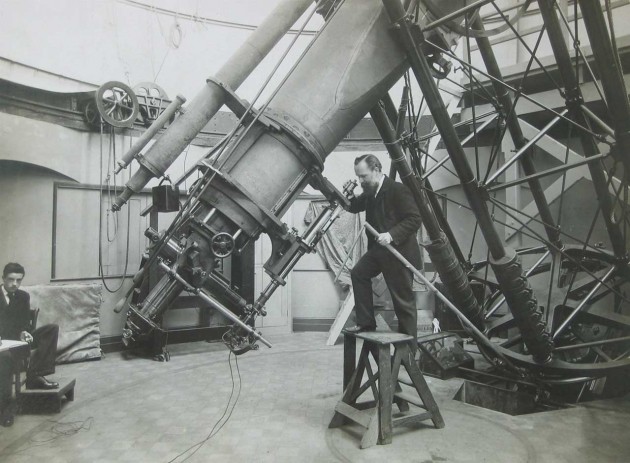

Double star observation in June 1895. Thomas Lewis is at the eyepiece, whilst his assistant William Bower records the micrometric measurements. Photograph by David Edney. From The Leisure Hour (1898). A cropped version of the photo was later used by Maunder in his book The Royal Observatory Greenwich (London, 1900)

Christie’s half-prism Spectroscope was mounted in June 1894. Later that year however, a regular programme of double star observations commenced together with a limited programme of spectrographic work. The latter was abandoned in November 1895 supposedly so that Maunder could concentrate on the heliographic reductions. The real reason is more likely to have been that in the years between the telescope being ordered and finally delivered, it had become apparent that the way forward with this work would involve not visual line-of-sight spectroscopic measurements, but photographic ones.

The double star programme had been started by Thomas Lewis on the 12.8-inch Merz in 1892. He initially carried out nearly the whole observing programme himself. He was joined in 1895 by William Bowyer, who took an increasing share in the work and observed three nights a week from 1902 to 1914. Lewis himself ceased observing in 1911. Regular duties were undertaken by Walter Bryant from 1897 to 1903 and again from 1906 onwards and by Herbert Furner from 1902. Observations were also made by Eddington and Chapman and a number of other observers. During the First World War, the instrument was put at the disposal of the double star observer Robert Jonckheere, Director of the Lille Observatory and a wartime refugee. After the war, the telescope was used to carry on a limited programme of observations until August 1919 when preparations were put in hand to dismantle it so that extensive repairs to the mounting could be carried out.

In some years, the telescope was also used to make micrometric measurements on the dimensions of the planets.

The 28-inch refractor with E Walter Maunder at the half-prism spectroscope. His assistant is William Bower, a computer, who became established in 1896. Photograph by David Edney, c.1895. Reproduced by permission of the Greenwich Heritage Centre (see below)

Resolving power

When two stars are very close together, they will be seen as a single star unless the telescope has sufficient resolving power. The greater the aperture of the object glass of a telescope, the greater its light gathering power (which means fainter objects can be seen) and the greater its resolving power. In the case of the 28-inch Refractor the maximum resolving power is around 0.16 seconds of arc.

Dismantled in 1919 and rebuilt in 1920

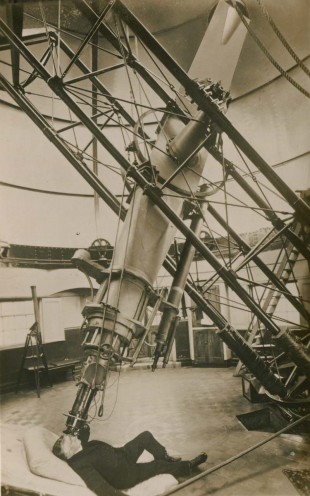

An unknown observer at the eye-end in the 1920s or early 1930s. Note the relocated guiding telescope. Postcard published by Royal Observatory, Greenwich

Working the double-image (filar) micrometer on the 28-inch Refractor in the late 1930s. The comparison image micrometer can be seen just above the observer's hands. The clock on the right is 'Molyneux' which is believed to have been substituted for 'Dent 2009' in the late 1920s

When the 28-inch telescope was supplied in 1893, it was fitted to the old mounting of the smaller equatorial, which dated from 1851. The mounting had, therefore, been in continuous use for 68 years. The casting, of which the upper pivot forms a part, having become badly worn, its replacement became necessary. As this entailed dismantling the telescope, it was decided to take the opportunity provided to replace both pivots by new ones working on Hoffmann ball bearings, mounted in swivelling frames, and also to replace the existing bottom thrust by a ball-bearing end-thrust. The work of dismantling the telescope and executing these repairs was entrusted to Messrs. T. Cooke and Sons, Limited. The delicate task of dismantling, made difficult owing to the confined space within the dome, was successfully carried out in October 1919. To facilitate this operation, and to provide a support for the polar axis while the repairs were in hand, a large wooden staging was erected by the Civil Engineer of the Royal Naval College. During the alterations the telescope was lifted out of the declination axis and the pivots examined and found to be in good condition. The repairs were completed in October 1920.

Although Dyson gave no further details, it was probably at this time that a number of minor modifications were made to the 28-inch Refractor. These include the removal of the remaining parts of the half-prism spectroscope together with the sliding eye-end arrangement and the relocation of the guiding telescope from above to below the 28-inch Refractor tube.

Observing programme 1920–1939

With the completion of the major repair programme mentioned above, the programme of double star observations recommenced on 25 October 1920 and continued until the outbreak of war in 1939. Following the arrival of Spencer Jones as Astronomer Royal in 1933, there was a notable reduction in the number of annual observations possibly a result of the deteriorating seeing conditions. In 1936/7, the observing programme was reorganised to secure additional observations. Part of the motivation for this was that by then, no other northern hemisphere observatory was prepared to devote the whole time of a large telescope to double star work. In 1937, the telescope was fitted with a comparison image micrometer. Made by Casella and Company, it was a modified version of one designed by Hargreaves. An illustrated description was published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, (Vol. 98, p.176).

As well as double star observations, the telescope was also used to observe occasional events such as the Transit of Mercury on 10 November 1927. On that occasion, the observer was Henry Furner and the aperture was reduced to 15 inches.

Between 1920 and 1939, the telescope was made available to a few individuals from outside the observatory. These included Commander Ainslie, Major Hepburn and Dr Stevenson who had use of the instrument in 1920/21 for the study of the rings of Saturn near the times of their disappearance and Dr G.V. Simonov of the Lembang Observatory, Java who used the instrument to make 114 observations of 44 pairs in 1938/9. Stevenson also had use of the telescope in 1926/7 when he used it to determine the magnitudes of Novae and faint stars beyond the reach of smaller telescopes.

The Astronomer Royal, Frank Dyson, showing showing the 28-inch Refractor to the King and Queen during their visit to the Observatory on 23 July1925 as part of the Observatory's 250th anniversary celebrations. From left to right: Herbert Furner, Frank Dyson, unknown, Sir Charles Sherrington (President of the Royal Society and Chairman of the Observatory's Board of Visitors), King George V, Queen Mary

Changes 1937–39: Telescope ventilation, an interferometer and an unmovable dome

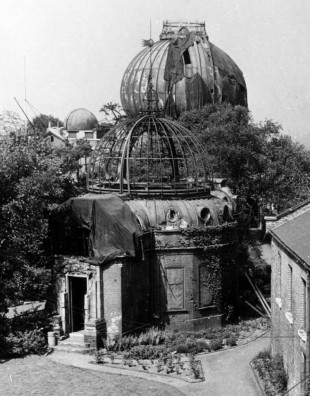

The Altazimuth and Great Equatorial Buildings at the end of the Second World War. Although the photographer is not recorded, it is likely to have been Cecil Beaton who, at the request of the Ministry of Information, made a photographic survey of the Observatory in the reporting year 1944/5. Detail from Ministry of Information photograph D.24700

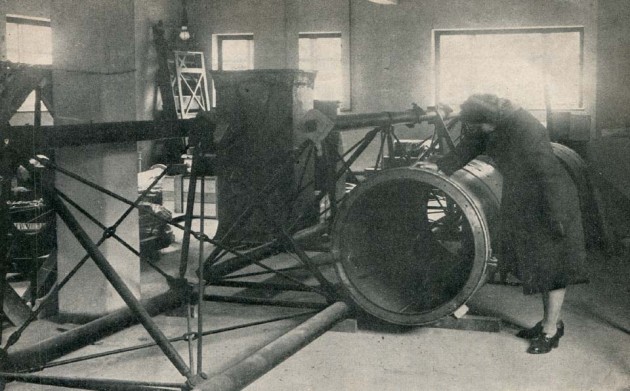

Removing the graduated circle at the base of the telescope for transportation to Herstmonceux. The workman on the left holding the rope is straddling part of the partially dismantled polar axis which is lying on the floor. From The Sphere, (6 December 1947)

In 1938/9, the dome shutter mechanism failed and the dome rail fractured. Having become un-turntable, in 1939/40 it was moved to a position that allowed the best selection of stars to be observed without moving it.

The Second World War

With the outbreak of war, the observing programme with the 28-inch on the Greenwich site came to an abrupt and, as things turned out, a permanent end. The object glass was dismounted for safety on 1 September 1939 and never remounted while the telescope remained at Greenwich. During night bombing raids during October 1940, the papier mâché covering was riddled with holes. Then on 15 July 1944 a V1 bomb that fell in the park nearby, stripped the dome of most of its covering. With the dome rail already fractured, the dome covering now beyond repair and a move anticipated to a new site, the decision was made not to bring the telescope back to use at Greenwich.

Transfer to Herstmonceux

Herstmonceux Castle and its 368 acre estate were formally acquired from Sir Paul Latham on 18 February 1947. Later that year the 28-inch Refractor was completely dismounted and the mounting partially dismantled prior to being transferred to Herstmonceux that December. Once there, the parts were placed in store in one of the hutments.

Removing the polar axis from the damaged dome at Greenwich. In order to remove the north pier, part of the brickwork had to be removed from either side of the double doors located next to the two men on the balcony. From The Sphere, (6 December 1947)

The dismantled 28-inch Refractor in store in one of the hutments in early 1948. It was removed from Greenwich in December 1947

The completed Equatorial Group from the south in about 1959. Dome F is on the right. From an old (RGO?) postcard

Re-erection of the 28-inch in Dome F of the Equatorial Group began in July 1957 and was completed that September. After three months of visual use, tests were carried out on its photographic performance. Rather than reversing the crown glass, a yellow filter was installed at the eye-end. This was held in a specially constructed angle-iron framework which also carried a plate-holder. In February 1958, the tests were brought to a premature end when the dome was taken out of service for structural modifications. The preliminary conclusion that was come to was that although not unsuitable for photography, the 28-inch was substantially slower than the 26-inch refractor.

In 1958/9, the telescope was fitted with a specially made dew cap complete with a rotating hexagonal stop controlled from the eye-piece end. The declination slow motion screw was motorised to give push button setting control and the telescope completely rewired electrically. The following year, 1959/60, a Barlow lens was fitted to effectively double the focal length of the object glass and the declination control motorised.

In August 1959, the object glass was tested by Hartmann’s method. Its figure was found to be adequate but the spherical aberration over-corrected. To eliminate this, the separation of the components was increased by 0.28 inches. The resulting zonal errors were smaller than any comparable object glass for which data had been published.

Observing programme at Herstmonceux

The double star programme was recommenced at Herstmonceux on 1 November 1957. Following a pause for the photographic trials and dome modifications (as mentioned above), the double star programme recommenced on 11 July 1958. It ended in 1970.

The telescope's return to Greenwich

With the telescope having become effectively redundant, a decision was made to offer it to the National Maritime Museum who had taken on responsibility for its original site at Greenwich site. Although other buildings had been demolished, the Great Equatorial Building, in which it had been housed, had been retained after the war though its damaged dome had been removed as it had been deemed unsightly. Originally the plan had been to install a giant orrery under a reconstructed concreted dome. This plan was then abandoned in favour of installing a planetarium instead. By 1961, the NMM had changed its mind again and proposed instead to install the Northumberland Telescope, from the Cambridge Observatory and put the planetarium in the dome of the South Building.

The Northumberland had been designed by Airy and had many similarities to the later 12.8-inch Merz at Greenwich. Its proposed erection at Greenwich was based on the understanding that it would soon be redundant and available for transfer. With the 28-inch Refractor suddenly being unexpectedly available and the Northumberland still in use at Cambridge, the Museum leapt at the opportunity to have it back.

A temporary scaffolded cylindrical covering was built over the dome walls and the telescope transferred from Herstmonceux during November and December 1971. On this occasion, part of the telescope tube was left attached to the polar axis during the transfer process.

The polar axis with part of the telescope tube being loaded onto a lorry at Herstmonceux. Photo courtesy of Patrick Moore

Click here to view a sequence of 23 photographs showing the telescope’s removal from Herstmonceux and its arrival at Greenwich.

The telescope remained protected by its temporary covering until the arrival of a new dome. This was constructed along the lines of that designed by Christie, but with a double skinned fibreglass rather than a papier mâché covering. The new skeletal Dome was craned into place in October 1974, prior to the coverings being applied. It was officially reopened on 20 May 1975 by Her Majesty the Queen who visited the site with HRH The Duke of Edinburgh as part of the Observatory’s tercentenary celebrations. Since then, it has been kept in working order and used as part of the Museum’s Education programme. The present Evening with the Stars programme was instigated by Graham Dolan in the 1990s.

Other large refractors with similar object-glasses

On page 305 of his book The History of the Telescope, (London, 1955), Henry King identifies the 13-inch Boydon and the 20-inch Van Vleck refractors as having object glasses made for both visual and photographic use on similar lines to that of the 28-inch Refractor at Greenwich. Both were made by Alvan Clark & Sons in America, the former in 1888 and the latter in 1922.

Published Observations

The listing below may be incomplete.Observations of Double Stars made with the 28-inch Refractor (1919–1923)

Observations of Double Stars made with the 28-inch Refractor (1919–1925)

Double-Star Observations made with the 28-inch Refractor 1957–1960. Royal Observatory Bulletins, Number 38. R.v.d.R. Woolley, D.H.P. Jones and M.P. Candy

Double-Star Observations made with the 28-inch Refractor 1960–1963. Royal Observatory Bulletins, Number 88. Sir Richard Woolley, L.S.T. Symms, D.H.P. Jones and M.P. Candy

Double Star Observations made with the 28-inch Refractor 1963–1970. Royal Greenwich Observatory Bulletins, Number 184. R.W. Argyle, M.P. Candy and L.S.T. Symms

The published observations made between 1894 and 1909 can be accessed via this link. Those made in the 1920s and 1930s can be accessed via this link.

Contemporary accounts

Mounting

Airy published a definitive technical account of the 12.8-inch Merz and its mounting in the 1868 volume of Greenwich Observations which was published in 1870. It contains 55 figures spread over 8 plates. These were drawn in 1868/9 by ‘an accomplished draughtsman’ under the superintendence of Airy’s assistant, James Carpenter.

Description of the Great Equatorial at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. Airy G.B. Appendix 3 to the 1868 volume of Greenwich Observations.

Dome

On a new dome to be erected at the Royal Observatory Greenwich. W.H.M. Christie. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 51, (1891), pp.436–38.

Historic film clips

G.H.Q. "Time". King and Queen visit Greenwich Observatory on its 250th anniversary. Shot in 1925, this British Pathé clip shows amongst other things, the Royal party in the 28-inch dome. Running time: 1 minute 25 seconds.

Visit of the King of Afghanistan to England. Shot in 1928, this film consists of 7 reels in total. The King’s visit to the Royal Observatory is on reel 4 of (7). Reel 4 starts with the Royal Party travelling by boat downstream to Greenwich. Observatory footage starts at 3min 5 sec. The King and the Astronomer Royal Dyson are seen entering the 28-inch telescope dome and examining the telescope. They are then shown examining the telescopes in the Thompson Dome in the South Building. The footage ends with the royal party on the South Building. Running time: 3 minutes 18 seconds.

The Sky at Night. This clip shows BBC footage of the telescope returning to Greenwich in 1971 together with part of an Evening with the Stars programme. Running time: 2 minutes 39 seconds.

Further Reading

The 28-inch Refractor at Greenwich – a History of Two Telescopes. Wright, D. C., Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol.31, NO. 4/DEC, P.551, 1990

Thomas Lewis: a lifetime of double stars. Wright, D. Journal of the British Astronomical Association, vol.102, no.2, p.95–101 (1992)

Sir Howard Grubb. Illustrated Interview from The Strand Magazine, Volume 12 (1896) pp.369–381

Victorian telescope makers: the lives and letters of Thomas and Howard Grubb. Glass, I. S. Bristol, UK: Institute of Physics Pub., 1997

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to the Greenwich Heritage Centre for permission to reproduce the photograph of E Walter Maunder with the half-prism spectroscope on the 28-inch refractor.

The photograph labelled: The polar axis with part of the telescope tube being loaded onto a lorry at Herstmonceux is reproduced from The Patrick Moore Collection courtesy of Patrick Moore

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan