…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

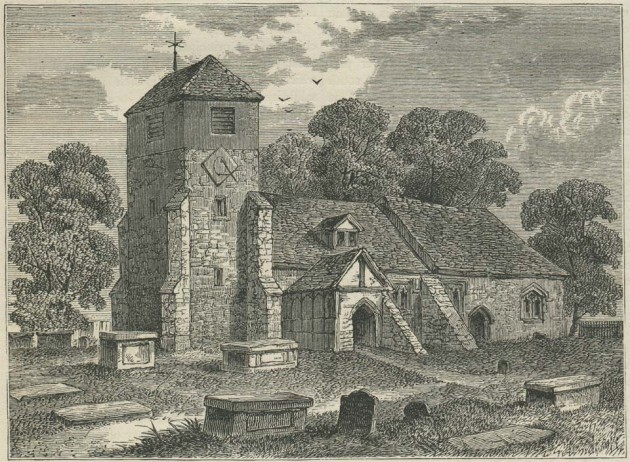

The old churchyard, St Margaret’s Lee: the burial place of Halley, Bliss and Pond – the second, fourth and sixth Astronomers Royal

Three of the Astronomers Royal are buried a mile from the Observatory in the old churchyard of St Margaret’s Lee. By a curious coincidence, the Greenwich Meridian as defined by WGS84 passes though the remains of the old church at its centre. The three Astronomers Royal are Edmond Halley, Nathaniel Bliss and John Pond. Halley and Pond are buried in the same tomb. The exact spot where Bliss is buried is unknown. His grave is unmarked.

The intriguing story of how they came to be buried at Lee rather than at St Alphege’s in Greenwich in which parish the Observatory is located, leaves many questions unanswered. So too does the available information on the restoration of Halley’s tomb in 1854.

Church |

||

| Address: | The old churchyard, St Margaret’s Church, Lee Terrace, Blackheath, London SE13 5DL | |

| Website: |

http://www.stmargaretslee.org.uk | |

| Phone: | 020 8318 9643 |

|

Edmond Halley |

||

| Dates in office: | 1720–1742 | |

| Born: | 1656, October 29 (exact date uncertain) |

|

| Died: | 1742, January 14 (Greenwich) |

|

| Interred: | 1742, January 20 | |

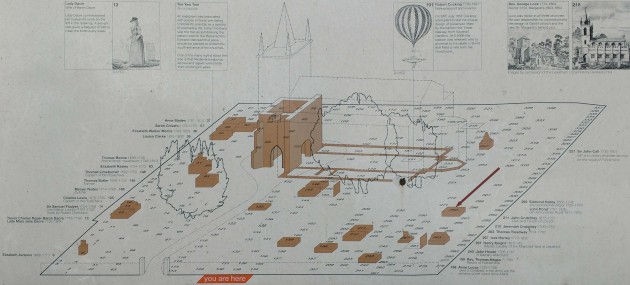

| Tomb location: | Table / chest tomb; East side of old churchyard near the boundary (see plan below) |

|

| Statutory listing: | Grade II (List entry Number: 1391994) | |

| Memorial plaques etc: | See notes below |

|

| |

||

Nathaniel Bliss |

||

| Dates in office: | 1762–1764 | |

| Born: | 1700, November 28 | |

| Died: | 1764, September 2 (probably at Greenwich) | |

| Interred: | 1764, September 4 | |

| Tomb location: | Unmarked grave (precise location unknown) | |

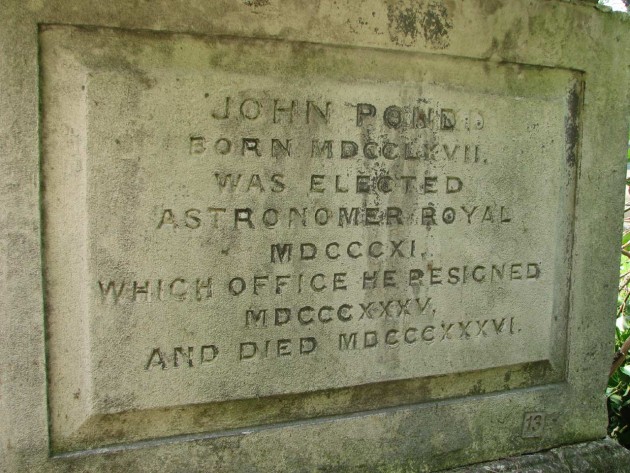

John Pond |

||

| Dates in office: | 1811–1835 | |

| Born: | 1767 | |

| Baptised: | 1767 on Nov 18 (privately) & 23 (publikly) at St Katharine Coleman, City of London | |

| Died: | 1836, September 7 (Blackheath/Greenwich) | |

| Interred: | 1836, September 13 |

|

| Tomb location: | Buried in same tomb as Halley (see above) |

A brief history of the church at Lee

In the time between Halley being buried in 1742 and Pond joining him in the same grave in 1836, the church of St Margaret was largely rebuilt. The original church of St Margaret was of medieval origin. By the start of the nineteenth century, it was in a poor state of repair. Apart from part of the tower, it was pulled down in 1813 to make way for a new building on the same site. This was designed by Joseph Gwilt and incorporated the original tower in modified form. Gwilt’s church was built on the old foundations and like its predecessor suffered from structural problems. The population of Lee grew rapidly after the church was built and it was soon apparent that a much larger church was needed. Most of Gwilt’s church was demolished on 31 May 1841 having been replaced by the present larger church which was built on the opposite side of the road and constructed between 1839–41 to the designs of John Brown. The new church was later altered by the architect James Brooks during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The current church is grade II* listed whilst the ruined tower of the previous two churches is grade II listed.

Halley’s grave

The old churchyard as seen from Lee Terrace on 5 October 2017. The arrow (right) shows the location of Halley�s tomb. An information board with a plan of the graveyard can be seen bottom right

Photograph of the plan on the information board. It shows the location of the more significant graves in the old churchyard. Those coloured brown are listed monuments. Halley�s grave (right) is marked with an arrow. Photo: 7 October 2017

Halley�s grave from the south-west. The inscription is on the stone tablet on the top. Photo: April 2007

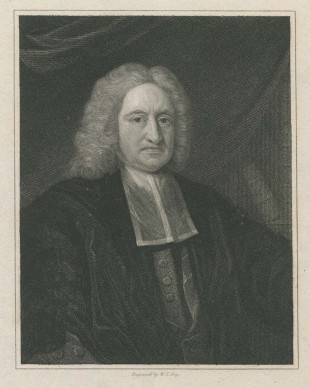

Edmond Halley in about 1736. Engraving by William Thomas Fry from an original picture ascribed to Dahl in the possession of the Royal Society. From Portraits of Eminent Men, Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, C Knight, London, 1845

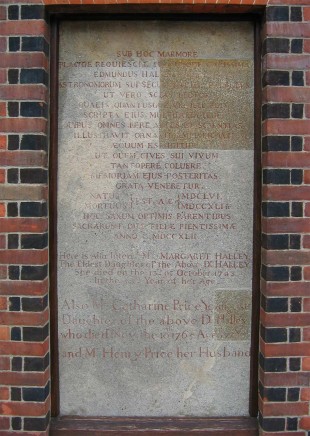

The original tablet carrying the inscriptions became dilapidated and was replaced with a copy when the grave was restored in 1854. This is the original. It was taken to the Observatory where it is now on display. Photographed at the Observatory on 7 September 2004

Halley’s wife predeceased him and was buried at Lee on 14 February 1736 (the burial register (preserved in the Lewisham Local History Archives) records her as ‘Elizabeth wife of Dr Edmund Halley’). His son died in 1740 and was buried at sea. We know that the reason why Halley was subsequently buried at Lee was because his will (which was written on 18 June 1736) stated his wish to be buried in the same grave as his wife. What we do not know, is why his wife was buried at Lee rather than in the home parish of St Alphege’s in Greenwich.

In all, five members of the Halley family are buried together in the same grave. This suggests a degree of pre-planning on Halley’s part, (as does the way that the inscriptions were laid out). Such a grave, would typically consist of a brick lined shaft with the bodies arranged in pairs in three layers, with the coffins in the upper layers being supported by pairs of iron bars fixed into the brickwork to separate them from the ones below. Such a grave would take time to prepare and perhaps one could not be provided in time at St Alphege’s (whose burial ground had been extended in 1716), but could be provided at Lee (where the last burial had taken place some two months before Mary died). Whatever the reason, for their interment at Lee, the Halleys were certainly not alone in coming from outside the parish. Of the ten individuals buried at Lee in the previous twelve months, just two appear to have been living within the parish. In those days, the church at Lee was in a tranquil open countryside setting whilst St Alphege’s was at the heart of all the hustle and bustle in Greenwich.

The grave does not appear to have been formally marked until after the death of Halley himself. He died at the Observatory on 14 January 1742 and was buried alongside Mary on 20 January. At this point, their daughters arranged for a suitable inscription in Latin to be added to the tomb.

‘Sub hoc marmore placidè requiescit, cum uxore carissimâ, Edmundus Halleius, LL.D. Astronomorum fui fæculi facilè princeps, ut verò scias lector, qualis quantusque vir ille suit, scripta ejus multifaria lege, quibus omnes ferè artes et scientias, illustravit, ornavit, amplificavit—æquum est igitur ut quem cives sui vivum tantoperé coluere, memoriam ejus posteritas grata veneretur. Natus est AC MDCLVI Mortuus est AC MDCCXII Hoc saxum optimis parentibus Sacrarunt diae filiae pientissimae Anno C MDCCXLI II. Hoc saxum optimis parentibus facrârunt duæ filiæ pientissimæ, anno CMDCCCXLII.’

A translation at the National Maritime Museum reads:

‘Beneath this gravestone, Edmond Halley, unquestionably the most eminent of the astronomers of his age, rests peacefully with his dearest wife. So that the reader may know what kind and how great a man [Halley] was, read his various writings in which he dignified, embellished and strengthened almost all the arts and sciences. And therefore, as he was a man so greatly cherished by his fellow-citizens during his lifetime, so let a grateful posterity venerate his memory. Born in the year of our Lord 1656. Died 1741/2. This stone was consecrated to excellent parents by two devoted daughters in the year 1742.’

A second translation which is quoted by Stuart Malin in an article on the Church website reads:

‘Beneath this marble peacefully rests, with his beloved wife, Edmond Halley, LL.D. easily the prince of astronomers of his age. Reader, to know his true greatness read his many writings, wherein he illustrated, improved and enlarged on almost all the arts and sciences. It is just, therefore, that as in life he was highly honoured by his fellow citizens, so his memory should be highly respected by posterity. Born 1656, died 1741/2. His two daughters most dutifully consecrated this stone to the best of parents, 1742.’

The following two inscriptions were added in English following the death of other family members and their burial in the tomb.

Here is also interred Mrs Margaret Halley the eldest daughter of the above Dr Halley she died on the 13 of October 1743 in the 55th year of her age.

Also Mrs Catherine Price youngest daughter of the above Dr Halley who died November the 10th 1765 aged 77 years and Mr Henry Price her husband.

In 1666 ‘An Act for Burying in Wool Onely’ was introduced to promote the woollen trade and reduce imports of linen. It was reintroduced in 1678 as ‘An Act for Burying in Woollen’. It required the dead, with the exception of plague victims and the destitute, to be buried in pure English wool. Those who ignored it and were buried in linen were subject to a fine of five pounds. The St Margaret burial registers record very few individuals being buried in linen. Between 1678 and 1754 just four individuals are listed. One of these was Halley’s daughter Margaret, for whom the fine was paid. Catherine (who died in 1765) was also buried in linen, but there is no mention of a fine. The act was generally ignored after 1770 but remained in force until 1814.

Lichen and moss have made the inscription on the tablet on top of the tomb all but illegible. Photo: April 2007

The burial arrangements for John Pond

The second Lee Church. This is how the church would have appeared at the time of Pond�s funeral. The building to the left is the vicarage. From Drake�s 1886 revision of Hasted�s History of Kent ... the hundred of Blackheath

John Pond was the first of the Astronomers Royal to retire rather than die in office. Afflicted by ill health, he resigned with effect from 30 September 1835. As a possible omen of things to come, his resignation coincided with the reappearance of Halley’s Comet which had last been seen in 1758. It was observed from the Observatory on various dates between 28 August and 9 November 1835 (click here to view the published observations).

Pond died at home on Wednesday 7 September 1836, almost exactly a year after he had retired. His obituary in the Morning Chronicle states his home was in Greenwich, but the one in MNRAS states it was in Blackheath, suggesting that it was somewhere between the two. He was buried on Tuesday 13 September. Identical reports of the funeral were published in The Times and The Standard on Thursday 15 September. The first section of the report is transcribed below:

‘On Tuesday last the remains of the late astronomer royal were deposited in the churchyard of Lee, Kent. They were attended to the grave by his successor, Professor Airy, by the three assistants of the deceased, by Mr Henry Warbuton, M.P., together with a few relatives and personal friends. Mr Pond having always expressed a desire that the place of his internment should be the beautifully-situated churchyard of Lee, application was made to the rector for his consent to carry the wish into execution, but, on account of the place being small, and already so full that room was with difficulty found for the actual parishioners, permission was not in the first instance granted. On reflection however, the Rev. Mr. Lock, recollecting that the tomb of a former astronomer royal, the celebrated Dr. Edmond Halley, who died in 1743, and was buried at Lee, had never been tenanted by a single individual except that distinguished philosopher himself, and his wife and daughter, and considering that, as 93 years [23 in The Standard] had elapsed since he was therein deposited, it was highly improbable that any claim would be made in behalf of his descendents, with very good feeling directed that the receptacle of Dr Halley’s remains should also become that of one of his successors. Thus, by an accidental and remarkable coincidence, the material part of two philosophers, who held the same appointment, who, while living, inhabited the same dwelling, now rest in the same grave. …’

Whilst some parts of the report are corroborated by Airy (who succeeded Pond as Astronomer Royal), others are not. In his journal (RGO6/24), on 7 September he recorded: ‘Mr Pond died at 7 this morning’ and on the 13 September: ‘Rainy. This morning I attended Mr Pond’s funeral; only Mr Main and Mr Glaisher left at home.’ Main and Glaisher were both appointed by Airy. The remaining four assistants, Belville, Richardson, Ellis Snr. and Rogerson had all been appointed by Pond and Airy implies that all four of them were in attendance. Given that Belville had been Pond’s ward (he arrived at the Observatory with Pond in 1811), it is possible that he was included amongst the relatives rather than the assistants in the report. There is no mention of Pond’s wife Anne. Although one might assume that this was because at that time, women often didn’t attend funerals ... there might perhaps have been another reason.

Airy appears to have recorded nothing of the funeral arrangements at this time, but when applying to the Admiralty for funding to restore the tomb in 1854, he wrote: ‘I may mention that my immediate predecessor Mr Pond was (at his own desire) interred under the same tomb.’ (RGO6/74/64)

If Airy is correct, then Pond could be regarded as some kind of Halley groupie who wanted to be as close to his hero as possible. If the reports in The Times and The Standard are correct, then perhaps he should be considered simply as a cuckoo in the nest. Either way, it seems inconceivable an individual would be buried in this way today. As the grave was now full, there was no prsopect whatsoever for Anne Pond (1789–1871) to be buried with him.

The inscription relating to Pond is on the east end of the tomb. Note the odd wording, particularly the use of the word elected. Note too, the uneven lettering, especially in the top line (particularly the two Ns) and the extra D at the end of Pond�s name. Photo: April 2007

The first restoration of Halley’s tomb

Airy is well known as a man who liked his walks and by all accounts, one of his favourites was from the Observatory to an oak in the vicinity of the churchyard that had a girth of four yards and was described as one of the finest in the county. It would appear that, from time to time, he would also visit Halley’s grave. In his 1855 Report to the Board of Visitors he wrote:

‘The Tablet upon Halley’s Tomb, in Lee Churchyard, had apparently received no repair since it was first erected. It had sustained injury, probably from the sinking of the ground, and the unequal dropping of the sides of the tomb; probably also from the strains to which it was exposed when it was taken down for the interment of my predecessor, Mr. Pond, in the same grave. On the last occasion of clearing off the moss from the inscription, I found the stone so much injured, that mere repair appeared hopeless. On my representing this circumstance to the Board of Admiralty, and representing also the public character of the tomb (the inscription is in Latin, and is such as belongs properly to a national monument), their Lordships immediately supplied the necessary funds for its restoration. In order to effect this, I commenced by taking a “rubbing” of the inscription, as a guide to be strictly followed by the masons in cutting the new stone; and the new engraving, in regard both to the excellencies of the inscription applying to Dr. Halley himself, and the faults of those applying to his descendants, is a rigorous copy of the old one.’

In Volume 1 of his series, The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent, which was first published in 1778, Hasted describes Halley’s grave as ‘a plain table tomb’, but makes no comment on its condition. By the end of the century, the grave was in a state of dilapidation. This was recorded by one of the Observatory’s assistants, Thomas Evans, who, in The Juvenile tourist (first published in 1804), describes the grave as being in ‘a very decayed state’.

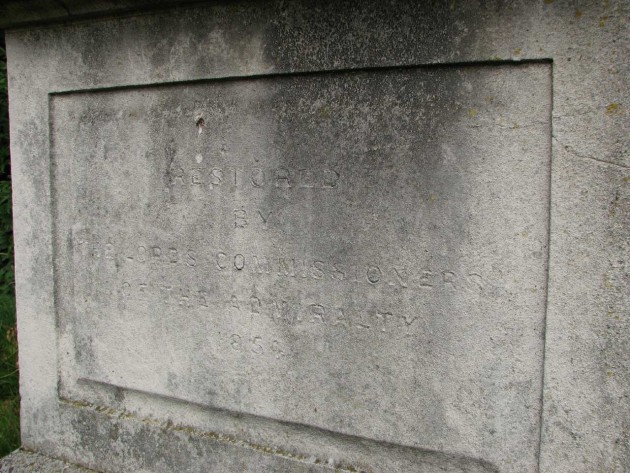

The west end of the tomb. The inscription reads �Restored by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty 1854�. Photo: April 2007

Under normal circumstances, the Admiralty would not have been expected to pay for the restoration of the grave of one of its former employees, Airy thought it wise therefore to sound out the Hydrographer of the Navy, Rear Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort, (to whom he reported), before making a formal application to the Admiralty for funding. His first communication to Beaufort is dated 27 January 1854. Beaufort wrote back the following day saying that he had not laid the matter before their Lordships but had ‘mentioned the matter as being desirable for the credit of the country’ and that they recommended that Airy write officially to the secretary. This Airy did, on 31 January, writing a very similar letter and repeating that the cost of the work would be fifteen pounds and seventeen shillings. The Admiralty wrote back on the 3 February, authorising the expenditure and asked Airy to ‘superintend the restoration’ (RGO6/74). The stonemason was C Thomas of Lewisham who also repainted the lettering in 1861 (RGO6/51).

It is not presently known how much of the original tomb was replaced during the restoration. The implication from Airy’s report and correspondence with the Admiralty is that it was just the top slab. It seems likely however that the bottom slab that covered the tomb was also damaged. But what of the four sides of the chest? It is worth pointing out that the inscription to Pond on the east end is distinctly uneven and odd, especially, the spelling of his name with a double D. Had the original panel on which it was cut been replaced, one might have thought that Airy would have commented. When the tomb was given a statutory listing of grade II on 1 June 2007, it was stated in the accompanying text that:

‘The tomb in Lee old churchyard was replaced in 1854 by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty’

and that:

‘Despite its simple design and 1850s date, the tomb meets the criteria for listing of commemorative monuments as the resting place of a distinguished person of national importance.’

There is a big difference between the tomb being replaced and the tomb being renovated (which implies some of the material was original). On the face of it, the listing text should be treated with a degree of caution.

The erection of the original inscribed tablet in the courtyard of the Observatory

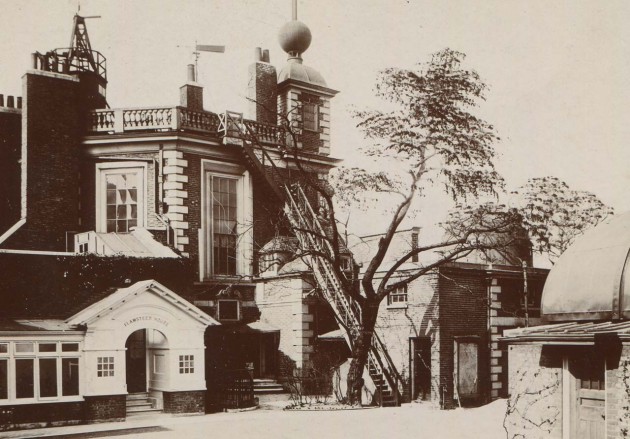

The original inscribed slab from the top of the grave (the tablet) was taken to the South Ground at the Observatory where for many years it appears to have been left undisturbed. Airy was a particularly methodical man who liked things to be well documented and properly preserved. Towards the end of his time in office as Astronomer Royal he reviewed his many records and published reports and put steps in place to tie up any loose ends. In his journal (RGO6/27) he records that on 28 January 1881 that he ‘looked at papers regarding Halley’s tombstone’ and that on 1 April 1881: ‘Halley’s tombstone [was] set up against the wall of lobby to chronograph room’ i.e. on the wall of the eastern summerhouse (which was also known as the North Dome. His 1881 Report to the Board of Visitors elaborates:

‘Halley’s ancient tombstone, after its removal from Lee Churchyard (where it has been replaced by a new stone with a fac-simile of the inscription), had been placed in the South Ground, where it has been lying for several years. It has now been carefully restored, and mounted on the east wall of the lobby of the North Dome.’

Flamsteed House and the Eastern Summerhouse (North Dome) in about 1907�09. The tablet from Halley�s tomb can be seen mounted on the wall to the right of the door at the bottom of the stairs leading up to the roof of Flamsteed House. Detail from a postcard published anonymously, but probably by Perkins and Son (P&S)

Flamsteed House and the Eastern Summerhouse on 4 June 2009. Maskelyne�s extension on the south side of the summerhouse was removed in the late 1950s and the tablet mounted in the centre of the re-instated external wall. The sign on the wall to its right tells a little bit of its history and carries the translation of the Latin inscription mentioned above

The second restoration of Halley’s tomb

By the turn of the century, the tomb was once more in a stated of some dilapidation. In 1908, in the run-up to the reappearance of Halley's Comet in 1910, E. Clapton, the Rector proposed that it should be restored. Once again, the question arose as to who might have the authority to carry out such work and once again, the Admiralty agreed to pay for the works, which were subsequently carried out in 1909 (RGO7/1).

The third restoration of Halley’s tomb?

On 17 February 1951, the Reverend N.E.W. Bradyll-Johnson, the Rector wrote to the Admiralty apparently seeking funds for a third restoration. The request was declined with the suggestion that the Rector apply instead to the Royal Society (Work17/369), Further research is required to establish if any funds were forthcoming and if any restoration work took place at this time.

Nathaniel Bliss

When the third Astronomer Royal James Bradley died in July 1762, Nathaniel Bliss, (who had succeeded Halley as the Savilian professor of geometry at Oxford), was appointed to replace him. He died suddenly on 2 September 1764, and was buried two days later at St Margaret’s, Lee. The location of his grave is unknown. He was survived by his wife Elizabeth and four children.

In his book A collection of epitaphs and monumental inscriptions which was published in 1857, Silvester Tissington records:

‘In Lee churchyard, Kent, close by Dr. Halley, is buried Bliss, the fourth astronomer royal, but without any inscription. The only mention of Bliss‘s name, at Lee, is in the register of burials, which terminates very abruptly. It is as follows : – “ The Reverend Mr. Nathaniel Bliss, of East Greenwich, was buried September 4th, 1764. He was” – ‘

The burial of John Belville next to Pond

John Belville, the Observatory’s Second Assistant, died on 13 July 1856 and was buried by the side of Pond’s grave on 18 July (RGO6/784). His funeral was attened by the Observatory’s First Assistant, Robert Main, but not by Airy who was abroad at the time (RGO6/24). No details are known of the other mourners. Nor is it known on which side of Pond’s grave Belville was buried (the grave is unmarked). At the time of his death, Belville was living in Hyde Vale in the parish of St Alphage, Greenwich.

The Halley memorial in Westminster Abbey

Halley’s Comet last returned in 1986. A memorial to Edmond Halley was unveiled on 13 November that year in the south cloister of Westminster Abbey by the then Astronomer Royal, Professor Sir Francis Graham Smith. It takes the form of a stylised comet. Click here to read more.

Further Reading

History of Lee and its neighbourhood. F.H. Hart, Lee, 1882

The register of all the marriages, christenings and burials in the church of S. Margaret, Lee: in the county of Kent from 1579–1754. Lewisham Antiquarian Society, 1888

Fabric of Life: Linen and Life Cycle in England, 1678-1810. Alice Dolan (2015)

© 2014 – 2025 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan