…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

Historic plans of Greenwich Park: an illustrated catalogue (1660-1950)

Although originally enclosed as long ago as 1443, the earliest known plan that shows all or part of Greenwich Park in any detail dates from the early 1660s.

Following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the next few years were a hive of activity in and around the Park. In 1661, Charles II ordered the demolition of the now derelict Tudor Palace. John Webb was commissioned to design a new one and repair and enlarge the Queen’s House. Work started on the Queen’s House in August 1661 and on constructing the new Palace (now the Old Royal Naval College) in 1663. In 1661, work also began on re-landscaping the Park under the supervision of William Boreman. The following year, Pepys recorded in his diary entry of 11 April:

‘At Woolwich, up and down to do the same business; and so back to Greenwich by water, and there while something is dressing for our dinner, Sir William [Penn] and I walked into the Park, where the King hath planted trees and made steps in the hill up to the Castle, which is very magnificent.’

Six months later, the Dutchman William Schellinks also noted the steps in his journal, recording in the entry for 25 October 1662:

‘On the hill in the park behind the [Queen’s] house two avenues of trees had been planted from the bottom to near the top of the hill, where it was too steep to climb up, steps had been cut into the ground to walk up in comfort.’

Andre Le Nôtre (1613–1700). Bronze copy made in 1913 by Adrien-Aurélien Hébrard from the original marble bust by Antoine Coysevox on the tomb of Le Nôtre in l'église Saint-Roch, Paris. Photographed October 2012 in the Jardin des Tuileries. Louvre inventory number: TU 108

Although there are no plans or other direct records of their input at Greenwich, it is suspected that the two Frenchmen, André and Gabriel Mollet were involved in the early stages of the Park's redesign as there is a warrant from August 1661 that refers to them as the 'designers of all his [the King's] gardens for altering them and making them into the neatest formes'. A later warrant issued on 10 November that year appointing Adrian May as 'supervisor of the French gardeners employed at Whitehall, St. James’s, and Hampton Court' but seemingly not at Greenwich, suggests that any input from the Mollets (if indeed there was any) was probably limited to just the initial design.

In May 1662, André Le Nôtre (who was designing the gardens for Louis XIV at Versailles), was asked to contribute to the designs. The only record of his input however is an annotated plan for a Parterre on the more level ground between the Queen’s House and the bottom of the Giant Steps (now often referred to as the Queen's field). Whether this was a new feature or a modification of a parterre designed by the Mollets is not known.

Money however was in short supply and although all the avenues of trees were laid out and the landscaping completed, work on the Parterre was abandoned before any of the planned fountains materialised. In 1675, having abandoned all work on the new palace with not even the first wing completed, Charles II ordered that the Royal Observatory be built 'within our park at Greenwich, upon ye highest ground, at or near ye place where ye castle stood'. The Observatory has featured on every plan of the Park ever since.

The layout of the Park remained largely unchanged until the early nineteenth century and even today the original layout still dominates. By the start of the twenty-first century, although much eroded, traces of a few of the Giant Steps were still visible as was the outline of the Parterre, which was still demarked by rows of trees – albeit not those originally planted.

Today (2025), the Park is in the care of The Royal Parks, a charity that was set up in 2017. In 2023, the charity began an ill conceived (and part lottery funded) 'restoration' of the Giant Steps and Parterre as part of their Greenwich Park Revealed project. On the project's completion The Royal Parks claimed to 'have revealed, restored and protected Greenwich Park's unique 17th-century landscape before it disappeared forever'.

Click here to read more about the 'restoration' of the Giant Steps

Shape, size topography and orientation of the Park

Greenwich Park is roughly rectangular in shape and is about 1000m long by 750m wide. Its central axis runs roughly 30o to the west of north. The southern end of the Park is fairly level and drops steeply in the centre to a lower level area at the northern end. There is a huge inconsistency amongst the earlier plans as to exactly where the changes in level are marked despite the fact that by the time the earliest was made all the major landscaping that we see today had long since been completed.

Today, LiDAR allows us to map the Park with the help of Lasers and pick out ground features and localised changes in level. The National Library of Scotland website allows users to examine and track a LiDAR (DTM) view of the Park in parallel with a range of Ordnance Survey maps from different periods

LiDAR (DTM) scan of the Park from around 2021 alongside the OS 1:2500 mapping from about 1950

Types of Plan

There are three types of plan of Greenwich Park:

- Those that were made of just the Park and nothing else (except perhaps the buildings immediately adjoining it)

- Those that come from a parish plan or a plan of the Manor of Greenwich

- Those that come from a map of a much wider area.

The orientation of the Park varies from plan to plan. Those that come from maps are always orientated with north at the top. The accuracy and amount of detail shown within individual plans depends on the purpose of the plan/map from which they were taken.

Enclosures from the Park for the use of the Observatory

Following the founding of the Observatory in 1675, additional land was enclosed for from Greenwich Park for Observatory use on a total of 12 occasions. One or two of these were temporary, but most were permanent. The earlier enclosures were generally authorised through the offices of the King’s Surveyor of Woods until 1810, and then though those of the Commissioners of Woods and Forests. After the passing of the Crowns Land Act 1851, the enclosures were authorised by Royal Warrant except in two very minor instances. (List of enclosures made by the Observatory from Greenwich Park).

Houses occupied by the Park Ranger

The post of Park Ranger was an honorary position appointed be the crown and the official residence was sometimes known as the the Ranger's House. Over the years, three different houses adjoining the Park have carried this name. They are:

1690–1806: The Queen's House

1806–1814: Montague House

1815–1896: The present Ranger's House (previously known as Brunswick House).

The five earliest plans of Greenwich Park

The five earliest detailed plans of the whole Park are the Pepys Plan (c.1677), the Gascoin Plan (1693), the Travers Plan (1695–7), the Woodlands Plan (1695–1710?) and the Wise Plan (1714?). Three of the five plans are undated and unsigned. The reason why the Woodlands and the Wise Plans were created is unclear, which makes them harder to date. Although there are certain features that ought to make dating more straigtforward, it cannot be established for certain if the cartographers portrayed these features correctly. In the case of the Woodlands Plan, it is possible that some features were added at a later date.

The features in question are:

- the appearance of the 'New Road' that was created when the road that ran underneath the Queen's House was diverted. From plans which are dated this would seem to have occurred after 1693 but definitely by 1697 as it is shown on the Travers Plan, but not the Gascoin one. The most probably date of its creation is 1697 as this is when Earl Romney became the Park Ranger and took up residence in the House

- the presence of otherwise of any of the four houses (or their predecessors) built in the late 1600s (and early 1700s?) on the 'waste land' adjacent to the western park wall between Great Cross Avenue and the southern corner of the Park. Using their most recent names, from north to south, the four houses in question are: Macartney House (by 1677), the Ranger's House (by 1696), Montague House (1702?) and Park Corner House (by 1696). The last two are said to have both been demolished in 1815, but further research is required to confirm this

- the presence or otherwise of the burial ground which was created in 1707 on part of the site of the Dwarf Orchard that had been laid out in the northeast corner of the Park by William Boreman during 1661–2. The burial ground was subsequently built on in 1808–1812. Although a substantial Mausoleum was built at the southern end of the burial ground under the supervision of Nicholas Hawskmore in 1713–14 and retained when the rest of the burial ground was built on, the only plan to show either it or the burial ground is one that was published in 1749. The remains of the Mausoleum still survive, though in a much altered state.

A comparison of the the features shown on the five earliest plans

Date |

Name of

|

Ice houseshown |

Ice houselabelled |

Named

|

Labelled

|

Unlabelled

|

Giant

|

Copses |

|

| c.1677 | Pepys | Yes | No | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12 | 13/14 | |

| 1693 | Gascoin | No | n/a | 7 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 15/16 | |

| 1695–7 | Travers | No | n/a | 7 | 5 | 0 | n/a | 15/16 | |

| 1695–1710? | Woodlands | Yes | No | 0 | 1 | 3 (4?) | 7 | 15/16 | |

| 1714? | Wise | No | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 15/16 |

Notes:

- Click here to read more about the ice house

- The conduits date back to Tudor times and were originally constructed to supply water to Greenwich Palace and afterwards to Greenwich Hospital. The schedule to the Travers Plan names them

- Click here to read more about the Giant Steps

- The copses were at the south end of the park and ran across its full width.

The Ordnance Survey maps

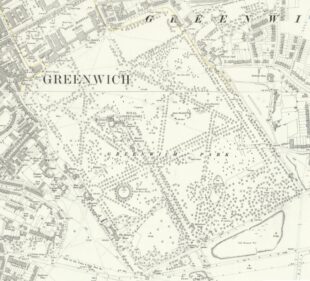

The earliest large scale Ordnance Survey map showing the Park is the so called Skeleton Survey of London that took place between 1848 and 1851 at the instigation of the Metropolitan Commissioners of Sewers. The mapping was carried out at a scale of five foot to the mile (1:1056), with the maps eventually being published at a scale of 12 inches to the mile (1:5280).

The first detailed survey of the Park took place in 1867 and was published at scales of 1:1056, 1:5280, and 1:10560

The second survey (or first revision) of the sheets showing the Park took place during 1893 & 1894 (though the whole of the Park may well have been finished during 1893. Like the 1867 edition, it was published at scales of 1:1056, 1:5280, and 1:10560.

The third survey (or second revision) took place during 1914 & 1915, with boundaries being revised in 1919. Unlike the early surveys, it only appears to have been published at a scale of 1:5280, and 1:10560.

On the 1:1056 mapping, the Park is spread across five sheets. On the 1:2500 maps it is spread across two and on the 1:10560 sheets the whole Park appears on one single sheet, each sheet of which covers an area of 6 x 4 miles.

Different sheets were surveyed or updated at different times. The dates given below are the dates that apply to the Park rather than the rest of each sheet.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the greater the scale, the more detail that is shown. What is surprising is that the amount of detail decreased with each new edition.

After the third revision, the next large scale maps to be published that show the Park date from a survey conducted between 1949 and 1951 and published at a scale of 1:1250. Because the adopted sheet size was small (about 22x 20 inches), the Park is spread over a total of 10 sheets.

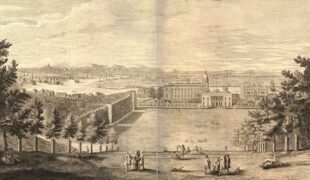

The Jonas Moore Manuscript Map of the Thames from Westminster to its source commissioned in 1662

The section of Moore's 1662 Map published by the London Topographical Society in 1912. Reproduced courtesy of Yale University Library (see below)

"A MAPP OR description of the River of Thames from Westminster to the Sea with the falls of all the Rivers into it the severall Creekes Soundings & Depths thereof and Docks made for the use of his Maties Navy, made by Jonas Moore Gent: by Warrant from Sr Charles Harbord Knt, his said Maties Surveyor General. In Pursuance of his Maties Warrant and Command under his Royal Signature Anno Domini 1662"

The royal warrant to which Moore referred is dated 7 February 1662.

The Map (now preserved at The National Archives (Work 38/331)) is large being more than six feet wide, two foot high and edged by a gold border with a black outline. Drawn on three pieces of joined velum, the Map has become rather rubbed over time, possibly in part, because of people brushing past it when it was pinned to an office wall. As well as showing buildings, the Map has a coat of arms (top centre), a cartouche containing the title above (bottom right) balanced by an image of a pair of dividers on a ruler (bottom left). There are also five good size watercolours? edged in gold. They are titled: The prospect of London (top left) and then in a row along the bottom from left to right: Greenwich, Wulwich (Woolwich), Erith and Graves End (Gravesend). They have been attributed by some to Wenceslaus Hollar, possibly on account of similarities between The prospect of London and known Hollar views. That said, no Hollar views remotely similar to the other four watercolours have been identified.

In 1662 St James's Park (which can be seen centre left) was in the middle of being landscaped for Charles II by the French Garden designers André and Gabriel Mollet who added the canal (in the centre of the Park) that runs from east to west. The Map shows the works in progress and is the only map known that captures the Park before 'the rounds' were added at the eastern end of the canal. However, when it comes to the way in which Greenwich was depicted, the Map is deficient. Not only is the landscaping of Greenwich Park not shown nor is the Park boundary or any of the redevelopment works that were taking place at Greenwich Palace. What the Map does show is the the route of the road running through the middle of the Queen's House and Greenwich Castle which appears to be shown in tact, even though it was prossibly a ruin at that point.

As far as is known, the complete Map has never been reproduced. However, the western third was reproduced in monochrome by the London Topographical Society in 1912 and the western half in full colour as the endpapers in Philippa Glanville's London in Maps (1972). Interestingly, the original seems to have suffered further damage since the 1912 copy was made. A cropped version of The London Topographical Society publication was included by Peter Whitfield in his book London in maps (2006/2017).

The copy of Moore's Map shown here is reproduced at reduced size from the digitized copy on the Yale University Library website (Call Number: 32 L84 1662/1912)

The Plan of the proposed parterre annotated by André Le Nôtre (André Le Nostre) in 1662-3?

Measuring 38.5cm x 29cm, this Plan in ink and sepia wash and was discovered in the Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France in 1955 by the Comte Ernest de Ganay. There is no record of how the Plan came to be there. Until its discovery there had been no definite evidence of Le Nôtre's involvement at Greenwich.Heavily annotated in French by two hands, the Plan is orientated with the Queen's house and its four proposed corner pavilions (marked E) at the bottom. Researchers seem to agree that all the text apart from the darker text at the top and the bottom is in le Nôtre's hand. In his book Gardens of illusion: the genius of André Le Nostre, Franklin Hamilton Hazelhurst suggests that the darker text at the bottom (which translates as 'Plan of The House of Grenuche [for] the Queen of England') was written by Le Nôtre when he was in later life. Others disagree.

The Plan appears to be the only surviving part of an ongoing correspondence between Le Nôtre and those laying out the parterre. It shows that at that time, the proposal was for the far end of the parterre to have a seven arched grotto on a raised terrace in front of which there was to be a large circular fountain, both being centred on the grand axis. Closer to the house, there were to be two smaller octagonal fountains symmetrically located on either side. The terrace walks on either side are shown sitting at a higher level than the floor of the parterre. A similar seven arch grotto designed by Le Nôtre had recently been constructed at Vaux-le-Vicomte just outside Paris and it was probably this work that inspired King Charles to seek his help at Greenwich.

The darker text at the top (not in Le Nôtre's hand) translates as 'The slope of the great Terrace is 229 feet long as you will see it marked - which is the same length as your arches as they were marked. The return corner is 30 feet and from there to the trees 52 feet as marked'. It is not clear if the dimensions given are in English feet of French feet which were about 1.066 times larger. Beneath the main plan, Le Nôtre has provided additional drawings which show the terraces with their dimensions marked together with seven numbered notes, the last of which includes two separate instructions to contact him at certain points during the work.

In the event, the scheme was abandoned, but not before the ground for the parterre had been leveled and the terrace walks bordering it constructed. Although the width of the level part of the parterre at the southern end is marked on the Plan as 229 feet, measurements of the parterre banks (as 'restored'; by the Royal Parks in the early 2020s) using Google Earth give a figure of about 200 English feet or 188 French feet. However, the plans submitted prior to the restoration and the LiDAR Plan of the Park seem to suggest that at that time it was very close to 229 English feet.

There is no evidence that Le Nôtre ever visited England and the siting of the proposed grotto suggests either that he was unaware of the Giant Steps or that their integration with the grotto was discussed in correspondence now lost.

Scandalously, although there are several mentions of Le Nôtre in the planning application submitted by The Royal Parks for the 2020s 'restoration' of the Parterre, no copy of the Le Nôtre Plan was submitted in the accompanying Heritage Statement nor was there any analysis of it. Nor were any of the other early plans of the park reproduced. Indeed the Pepys Plan – which is the earliest plan of the whole park – was not even mentioned. However, a rather better (though flawed) historical summary was provided in the Greenwich Park Conservation Plan 2019–2029. This undated document includes a good copy of the Le Nôtre Plan (p.37). Prepared by the staff of The Royal Parks, it was, according to their Annual Report and Accounts, published during the year 2019–20. A good copy of the Plan was also included by John Bold on p.13 of his book Greenwich (2000).

Because of the way in which the Park evolved in the 1660s, the Le Nôtre Plan cannot be considered in isolation (although this seems to have been largely the case in the past). We know that Le Nôtre's help was only sought for the first time in May 1662. But we also know for certain (see next section) that the giant steps, the 16 coppices at the south end of the Park and four walkes were in existence by June 1662. What we don't know for certain is if the four walkes all consisted of tree lined avenues. Nor do we know where in the Park they were located though we can make an educated guess about some of them (see next section). Nor do we know what other avenues had already been planted or planned prior to Le Nôtre's involvement. Nor is it clear if Le Nôtre's help was sought for planning the Park in general or just for the parterre and perhaps the formal gardens to the north of the Queen's House. As a result, we don't know how many of the tree avenues shown in the Le Nôtre Plan were designed by him and how many already existed.

The design for the Parterre is all about symmetry. But a closer look at the Plan shows the two diagonal avenues going off at different angles to the central axis. This is important, because unlike the other avenues shown on the plan, they both continue up the scarp to the plateau that makes up the southern end of the Park. Whether the intention was for them to be the same is difficult to decide as later plans are inconsistent in the way they portray them. The left diagonal proceeds roughly along the line of a natural valley suggesting either that Le Nôtre must have had some knowledge of the topography of the Park or that the basic layout had already been decided before he became involved.

Whether or not Le Nôtre ever came to England is discussed at length by Mrs Evelyn Cecil in her book A history of gardening in England (1910) pp. 178-193. Much quoted, its reading is recommended.

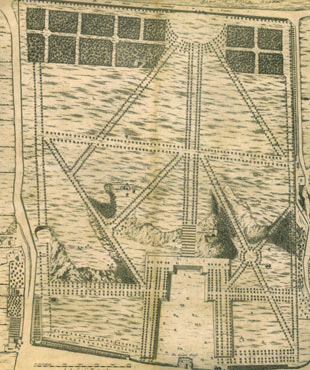

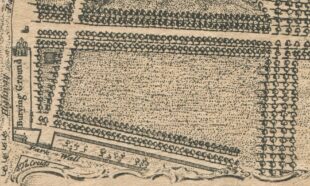

The Pepys Plan c.1677

Built on the site of Greenwich Castle, the foundation stone of the Royal Observatory was laid on 10 August 1675. The first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, took up residence in July 1676 and about a year later, or perhaps the year after that, Robert Thacker, an employee of the Board of Ordnance, made a series of drawings of the Observatory and its instruments. Although the drawings are now thought lost, twelve contemporary etchings made from them by Francis Place survive in small numbers. Two show the Giant Steps whilst another is this Plan of the Park. It is the earliest known plan that shows the whole of the Park and measures about 47cm x 52cm. Likewise, the two etchings showing the Giant Steps are the earliest known illustrations that show them.Only two copies of the Plan are known to survive. One is held by the Pepys Library in Cambridge from which the Pan takes its name. The other was discovered by Derek Howse in the collections of the Greenwich Local History Library (which was later merged with the Borough Museum to form the Greenwich Heritage Centre which was later reconstituted as Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust). The Plan is untitled and is an unusual hybrid of plan view and bird's eye view, the viewpoint for the latter being an imaginary elevated position to the north of the Queen's House which is at the bottom. The Parterre is shown in perspective view and for this reason, the east and west Parterre banks do not run parallel to each other as might otherwise be expected.

Information about the early relandscaping of the Park is preserved in the financial accounts of Sir William Boreman in the following two locations at The National Archives:

- SP29/56 (Secretaries of State: State papers domestic, Charles II. Letters and Papers)

- E351/3428 (Exchequer: Pipe Office: Declared accounts. Works and Buildings (Miscellaneous). Sir William Boreman. Works in Greenwich Park)

SP29/56/39&39.1 are single page documents. The first is a covering letter from Boreman that begins 'May it please yor Majesty'. The second is an unaudited breakdown of the money expended on the redevelopment of the Park between 1 September 1661 and 10 June 1662. The account is presented in three sections under the following headings:

- 14 Coppices

- 7 Walkes

- 12 Assents

E351/3428 contains Boreham's certified accounts for the period 1 September 1661 – 10 June 1662. Not only are these more detailed than those in SP29/56, but the money is accounted for differently. Spellings are different too. Of greater significance however is the fact that the stated number of Coppices and Walkes are also different. The numbers recorded in the document are:

- Coppices: 16

- Walkes: 4

- Ascents: number not specified

The number of coppices is also recorded as 16 in Boreman's accounts for the period 1662–1665 (SP29/116/14).

What this suggests is that the SP29/56 account was based on what had been planned and the E351 account on what was actually constructed. The coppices were at the southern end of the park and normal practice was to fell each coppice on a 14 year cycle, which would explain why 14 were originally planned. What is interesting is that the Pepy's Plan shows 13/14 coppices but all four of the plans that followed show 15/16 (the Gascoin Plan (1693), the Travers Plan (1695–7), the Woodlands Plan (1695–1710?) and the Wise Plan (1714?)).

This raises the intriguing possibility that the Pepys Plan was copied with some modifications from a now lost masterplan or artists impression that was drawn in 1663 or 1664 shortly after Le Nôtre became involved and that the masterplan itself was based on one of a couple of years before. This seems all the more likely as Sir Jonas Moore who commissioned the etchings from Thacker and Place was Surveyor General of the Ordnance and would almost certainly have access to any existing plans of the Park ... and why create an entirely new plan when an earlier plan could be easily adapted?

It would have been simple enough for Thacker or Place to copy the earlier plan, replace the Castle with the Observatory and scrub out the fountains from the Parterre. If this was the case, the failure to change the number of coppices from 14 to 16 requires explanation. Perhaps the exact number was considered unimportant. It is also possible, given their distance from the Observatory, that neither Thacker, Place nor Flamsteed realised that the number shown was no longer correct.

Although it never happened, Flamsteed originally planned to publish all or most of the 12 Francis Place etchings in his Historia in the manner of earlier astronomers. As such, they were designed to show the Observatory in the best possible light. An earlier masterplan showing the avenues as complete would have suited Flamsteed's needs very well even if at the time of the Observatory's founding there were still many trees to be planted or re-planted.

The Thacker/Place topographical views are generally considered to be be accurate representation of what existed when they were drawn. Given that they the etching Facies Speculae Septen show just nine steps, it seems likely that just nine rather than twelve were originally constructed.

Facies Speculae Septen. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.949

Given that the Plan shows a semi-circle of trees (the rounds) with three radiating avenues (the patte d'oie) at the top of the plan, we can be pretty sure, sitting as they do between the two sets of coppices, that they were amongst the seven avenues that Boreman had planned to lay out. But we also know from the entry for 25 October 1662 in the journal of the Dutchman William Schellinks that an avenue had been planted on either side of the lower part of the Park as he wrote:

‘On the hill in the park behind the [Queen’s] house two avenues of trees had been planted from the bottom to near the top of the hill, where it was too steep to climb up, steps had been cut into the ground to walk up in comfort.’

Given the date, unless they were dug up soon after, it seems highly unlikely that the two avenues were in the same location as the terrace walks whose construction is unlikely to have started by then (or much before then) and where avenues of elms are believed to have been planted in 1664.

There is no contemporary account in which the number of etchings completed by Place for Flamsteed is definitively recorded. Given that there are only two known copies of the Pepys Plan, some have questioned whether it was really part of the set. The evidence that it is, is circumstantial but compelling. Firstly, when Pepys came to mount his collection of topographical prints in 1700, he mounted all the Francis Place etchings together (twelve in total), with the Title Plate being glued onto the rear of the Plan (which was folded in). More importantly, when writing to Abraham Sharp on 21 April 1721, Joseph Crosthwait (who was preparing Flamsteed's Historia for publication) wrote:

'There are about three sheets of the observations to print; which, as soon as finished, shall be sent you, with the pictures you desire. I should be glad to know whether you had ever the map of Greenwich Park, the Plan of the Observatory, with the different prospects of it, sent: if you have not, I will send them, as soon as some few alterations are made in the plate of the Park.' (Baily p.343)

Although the alterations were not specified, it is known for a fact that the scale on the Pepys Plan is incorrect. It should have read ‘Scale of ‘Yards’, not ‘Scale of ‘Feet’. It is quite possible than it was also planned to change the number of steps on the Plan from twelve to nine and perhaps also to alter the number of copices to 16. If the alterations were ever made and any amended plans printed, none of them are known to survive.

In his autobiography, Flamsteed makes reference to the walks and one of the terraces when describing how he calibrated his Equatorial Sextant which was brought into use in 1676:

'Close by the foot of the hill, on which the Observatory stands, there is a terrace, that had been found very plain and even when the walks were made. At the west end of this I caused a frame to be built, parallel to the plane of the walk whereon to lay the sextant, with contrivances on it to fix the instrument very firm: from whose centre, to the other end of the walk, by the help of strong pikes I measured the distance 8762 inches precise. At this distance I placed a long, strong, flat rail, well fixed and supported: and having computed how many feet answered to a degree, marked them off on this rule; which was made so long as to subtend an angle of five degrees. Then bringing the threads in the fixed telescope to the beginning of the divisions, and firming it close, I moved the screw; and carrying the moveable index along the limb, noted what revolves and parts were marked by it when the threads covered the divisions of the five next degrees. And repeating these trials oft, and carefully, made at last the table for turning the revolves and parts observed, into degrees, minutes, and seconds, which I made use of in all my observations of this, and the next following year.' (Baily's Flamsteed)

Exactly where Flamsteed was talking about is not entirely clear. It may have been the terrace at the bottom of the giant steps, or alternatively, it may have been the western end of the Cross Walk (which is specifically labelled on some of the later plans). What is interesting is that the terrace 'had been found very plain and even when the walks were made' suggesting that rather greater precision was applied in their original construction than in the renovations that took place in the Park in 2023/4.

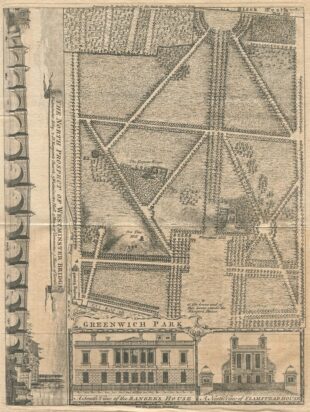

The Gascoin Plan of 1693

Measuring 79cm x 118cm and drawn on parchment at a scale of 1 inch to 8 perches (about 40m) this Plan is stored rolled. It is grubby and much rubbed, particularly at the left and right edges. It is housed at the National Archives (MR1/329) and carries the title:

'An Actual SURVEyof the ground wereon their MASTIES antient Palace at GRENWICH (in the county of KENT) formerly stood wth the buildings theron newly erected and of the adjacent Park.'

Click here for a larger view of the left half. Click here for a larger view of the right half.

A key in the bottom left hand corner contains about 40 entries and is headed: 'A Table of names for the respective parts of this Survey, wch was taken June 1693.' The entries that apply to the Park (some of which are difficult to read because of rubbing on the left hand edge) are as follows:

| A | the Queen's house | N | castle Hill | |

| B | the Elm Nurserys | O | the Royal Observatory | |

| C | the Dwarfe orchard | P | the Ascent | |

| D | the Terrace Walk | Q | Snow hill Walk | |

| E | the Cross walks | R | Conduit Walk | |

| F | the Chestnut Nurserys | T | the great Cross walk | |

| G | the Ponds | V | the Lodge | |

| H | the Gravell pitt | W | the great Wilderness | |

| J | the Conduits | X | a house used for fire works | |

| K | the five tree hill | Y | the Rounds | |

| L | Pauls Walk | Z | the little Wilderness | |

| M | Eltham walks |

The catalogue entry states the Plan was drawn by Joel Gascoin (Gascoyne?). Although his name does not appear to be present on the Plan itself, the form of the compass rose is similar to those on other plans he is known to have drawn. It also has a typically elaborate Cartouche.The Plan has misshapen features of which the most obvious is the lopsided Parterre immediately to the south of the Queen's House which still has the roadway running beneath it.

The stretch of land running outside the western park wall from Great Cross Avenue to the southern corner of the Park is marked as 'Mr Snapes house and garden'. The only buildings shown there are both on the site of Macartney House. The Rangers House is definitely not shown, nor does Park Corner House appear to be. A building may possibly be shown where Montague House was built, but further examination is required as it is not presently clear if the marking was made by Gascoin or if it is damage that has occurred as a result of rubbing.

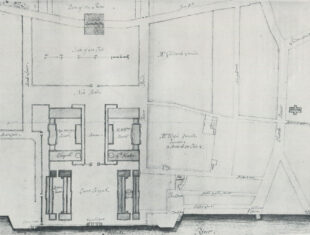

The Travers Plan commissioned 7 November 1695, completed 1697

Detail showing Greenwich Park from the Travers survey. Lithographed at a reduced size by J & J Neele for inclusion in John Kimbell's An account of the legacies, gifts, rents, fees &c. appertaining to the church and poor of the parish of St Alphege Greenwich, in the County of Kent, ..., which was published in 1816.

'A SURVEY of the KINGS Lordship or Manor of EAST GREENWICH, in the County of KENT, within ye Bounds & Perambulation of ye Parish of GREENWICH; The PARK and DEMESN-LANDS there; With the Remains of His Maties PALACES and MANSION-HOUSES Situate either within or without the Limits of ye Ground lately Granted for Erecting an HOSPITAL for SEAMEN: As also the several CONDUIT-HEADS from whence the said Palaces and Mansion-Houses are or ought to be supplied wth Water, And the WAST-GROUND belonging to the said Manor, with the BUILDINGS and IMPROVEMTS. thereupon.

All which is truly described as ye same was found by ye View and Perambulation of the Commissioners and a Jury Impannelled and on Examination of Witnesses for that purpose by Virtue of His Maties Commission under ye Great Seal of England bearing date 7.o Nov. 1695. By SAMUEL TRAVERS Esqr. SURVEYOR GENERAL.'

The original Travers Plan (from which the copy by Kimbell/J&J Neale shown here was made) is drawn on parchment, coloured and measures 129.5 cm x 134 cm. It is preserved at the National Archives (MR1/253) and has an accompanying schedule (MPE1/245).

Click here to read a transcript of the schedule. Click here to skip straight to the key.

When copying the Original, Kimbell/J&J Neale reduced the scale by a factor of two (making it roughly 60 cm square) and omitted much of the embellishment. Some of the labeling was also omitted, some of the wording modernised and the case of some lettering altered. In the copying process, at least one building not shown by Travers was added. Some of those omissions relevant to the digitised section shown here have been marked in pale green. They are:

- The labels for conduit Nos. 3, 4, &

- The label for the Ascent

- The label for the Terrace Walk(s).

- The 'house for fireworks' at the top of the Park

In common with the Gascoin Plan of 1693: the Parterre is lopsided and not properly centred on Blackheath Avenue. It would seem therefore that Travers copied this element from the earlier plan.

The stretch of Land running outside the western park wall from the current Macartney House to to the southern corner of the Park is recorded in the accompanying schedule as 'Three tenements and garden on the park wall, in the possession of Col. Stanley and others, now in lease to Nicholas Locke...' The buildings appear to be on the sites of Macartney House, the Rangers House and Park Corner House (now demolished). Montague House (also now demolished) is not shown.

The Woodlands Plan, 1695?–1710?

The Woodlands Plan was acquired by the Local History Library in Greenwich in the early 1970s from the collection of the Blackheath antiquary Alan Roger Martin. It is now in the care of Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust. Its earlier provenance is unknown as is the surveyor, purpose, date and meaning of some of the symbols used. It was examined by Land Use Consultants (LUC) in the mid 1980s and referred to by them as the 'Woodlands Plan' in their excellent and hugely useful Greenwich Park Historical Survey which was published in 1986, and the name seems to have stuck. It takes its name from Woodlands House which is where the Local History Library was located at the time.LUC speculated that the gaps shown in the avenues of trees in the Woodlands Plan may have been the result of the Great Storm of 1703. Over the years, this has been restated by others as fact and become deeply embedded. What LUC actually said was (p.52):

'The 'Woodlands' plan, made sometime between 1703–20, confirms great losses of plateau trees [at the south end of the Park] compared to those shown in a 1695 Plan [The Travers Plan]. This was probably due to the great storm of 1703, or may in part simply reflect the difficulties of establishing trees in the free draining plateau soils'

The speculation about the losses being due to the storm of 1703 is demonstrably incorrect as similar losses are shown on the 1693 Gascoin Plan. Although LUC were aware of the 1693 Gascoin Plan on which the Travers Plan is partly based, they had clearly either never looked at it, not looked at it properly, or had a memory lapse. Likewise, it is also worth noting that the Travers Plan does not show the location of any trees.

Dating the Plan has proved tricky owing to a number of ambiguities. The presence of the 'New Road' at the bottom suggests a date no earlier than 1697. However, the Plan does not show a building on the site of Park Corner House which is known to have been on the site by 1696 at the very latest (Cres 2/1642) and is shown on the Travers Plan which was compiled during the period 1695 to 1697. The number of Giant Steps is also problematic as significantly fewer are shown than on the Gascoin Plan of 1693. Another problem in dating the Plan is the arrival of a wooded area immediately to the east of the Giant Steps and another near the Blackheath Gates immediately to the north of the Great Wilderness (the area of coppices to the east of the central axis). Neither is shown on the Gascoin Plan, but they are shown on later ones. Given the ambiguities on both this Plan and the Wise Plan that follows, it is entirely possible that the Wise Plan is in fact the earlier of the two.

The 1731 view of the Scots Pines. Urbis Londiny Fluvy Thamesis, Templi Palaty, Viridary Greenovicensium ab Austro Conspectus engraved by Claude Dubosc after Alexander Gordon. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum Number: 1880,1113.5519 (see below)

Another unknown in the chronology of the Park is the date of planting of the single tree (here surrounded by a fence) on the hill to the east of the Observatory which has been known as 'One Tree Hill' since at least 1749. The tree does not appear on the Gascoin Plan, where this part of the Park is labelled as 'the five tree hill'. Nor does it appear on the Travers Plan, which labels the hill as 'Five Tree Hill'. Given the exposed nature of the site, it is entirely possible that the existing trees on the hill were blown down in the storm of 1703, especially as we know for a fact that three of the equally exposed chimneys belonging to Flamsteed House were blown down. If the tree was planted after the storm, this would date the Plan to 1704 or later. Also shown for the first time is a second tree to the south that is also protected by a fence which is surrounded by a circle of trees. This is marked on later maps as Queen Elizabeth's Bower. Although the trees no longer exist, the avenue leading up to it from the Blackheath Gates is still known as Bower Avenue. The central tree appears to be on (or close to) the site of a Roman temple that has since been excavated on a number of occasions, most recently in 2024. At present, little seems to be known about why the Bower was created, nor when the trees disappeared.

All the annotations together with the road system beneath the Park are a different colour to the rest of the Plan (including the distance scale) suggesting that they may have been added at a later date. It also seems strange that the road system with the 'New Road' at the bottom of the Plan is disconnected from the rest of the road network. A further examination of the original Plan may help shed light on this.

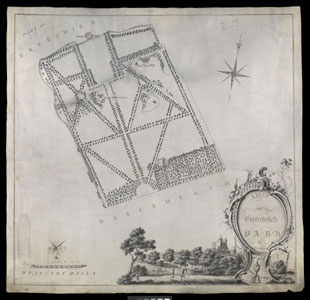

The Wise Plan c.1714?

This Plan is named after the Royal Gardner Henry Wise (1653-1738) who is believed by some to have once owned it. Like the Woodlands Plan, it is a bit of an enigma.Measuring about 79.5 x 54.5 cm from just outside the border, it is undated, unsigned and unfinished. Apart from two text panels, and a line stating the Park's acreage there are no other annotations and no scale is recorded. The left hand panel contains the title, whilst the other contains no text apart from a heading 'THE EXPLANATION'. Why this Panel was never completed remains a mystery. Despite the Plan's incomplete state, it was clearly valued sufficiently for it to have survived to this day. The title reads as follows:

' AN EXACT PLAN OF GREENWICH PARK describing all things thereunto belonging & adjacent: Viz the Queens house there, Keepers lodges, Avenues, Plantations, Hills, Vallys & other things remarkable therein; together with the Royall Hospital. Town of Greenwich, River of Thames'

The two headings are both poorly centred in their text panels. The Plan is coloured with a limited colour palette (the trees having browny black trunks and green foliage) and is drawn on two sheets of thin paper (with the top section being nearly twice the size of the bottom). It is currently in the care of the National Maritime Museum and can be viewed in full colour on the Museum website:

The Plan was purchased at auction for the Museum by Messrs Spink who were acting for Sir James Caird, a major benefactor. It was part of Lot 128 in Christie's Sale of 12th December 1947 and had been put up for sale by the executors of Sir Wathen Arthur Waller, bart. of Woodcote, Leek Wooton, Worcestershire (the lot also included at least two other plans including one of Kensinton Gardens which Caird donated to the Ministry of Works (WORK 32/309) and another that is mentioned below).

When acquired by the Museum, the Plan was rolled and attached to wooden batons at the top and bottom and backed by what appears to have been a sheet of canvas (or hessian?).

The canvas backing has now been removed and both it and the Plan are stored flat but separately in the same protective wrapper. The paper on which the Plan is drawn has not stood the test of time. There are small losses (top left) and numerous cracks and tears most of which are horizontal and presumably occurred as when the Plan was rolled and unrolled. It has since been mounted on a paper (thin canvas?) backing to preserve it.

Over time, contact between the Plan and the canvas created a ghost like imprint that is clearly visible on both sides of the canvas. The back of the canvas carries the words GREENWICH PARK (top centre) immediately below which is the Numeral 7. At right angles to this and near the right hand margin X¼ has been written, the significance of which is unknown.

The Plan is missing the 'new road' which is thought to have been constructed in 1697 as well as other roads nearby of earlier date, but does show the buildings of Greenwich Hospital as drawn in the Hawksmoor Plan of about 1701 (the Hospital was completed to a modified design in 1751). It is the first plan in which all four of the houses constructed adjacent to the western park wall at the southern end of the Park are shown (Macartney House, The Rangers House, Montague House and Park Corner House). This would date it to about 1702 or later.

The avenues are shown with no loss of trees suggesting either that the missing trees in the earlier plans had been replanted or that this was a very idealised view of the Park. That it is an idealised view is supported by the fact that the avenue at the side of the park (bottom left) is shown as two rows of trees as it approaches the corner of the park, whereas on all other plans it is shown only as a single row at this point.

The Plan also shows the Giant Steps and the Scots Pines that are shown on the Woodlands Plan. One significant difference is that just six rather than seven steps are shown, another is that the steps are shown with uniform treads and risers, something that also suggest that it is an idealised view. Having said that, both plans appear to show the same number of trees in total at the end of the treads.

Like the Woodlands Plan, the Wise Plan also shows Queen Elizabeth's Bower. It does not however show the single tree on One Tree Hill. Its absence suggests either that the Wise Plan predates the Woodlands one, or that it was omitted in error.

The second plan in Lot 128 to which Haynes refers (b/w copy). It has been cropped to just within a thick lined border and is roughly 2.5 times smaller than the plan of Greenwich Park. It is inscribed in a contemporary hand on the rear with the words Land of Mr Wises at Greenwich.

'The likelihood that both the [Park] plan CMP/30 and the smaller drawing relate to this sale is strengthened by the identical depiction in both of the, as yet unbuilt, hospital buildings. They are presented in a design put forward for these buildings by Hawksmoor in 1701, rather than the design to which they were finally built. Hawksmoor's proposal is reproduced by Bold as illustration 146 (Bold 2000, 107). Since Hawksmoor advised the Directors on the purchase of the land for the Infirmary (Bold 2000, 208), it is plausible to suggest that Bridgeman had access to that plan, through Wise, who had employed him in c.1714, to produce a presentation drawing of Greenwich Park, to show the land Wise was selling in the context of the rest of the park.'

This does not stand up to scrutiny. Even in poor quality reproductions, it is quite obvious that the hospital buildings are depicted differently in all three plans. Not only that, the 'new road' has been omitted on the Park plan, but not on the one showing Wise's plot of land. Nor does Haynes explain why the plan showing the plot of land has been folded in half and in half again and in half again whilst the larger Plan of the Park does not seem to have ever been folded at all. And finally, if Hayne's speculation is correct, why would such a large Plan of the Park have been made?

So when does the Plan date from? We can be pretty certain that it dates from 1702 or later. Although it is not known when they were planted, the presence of the trees at the ends of the Giant Steps suggests that the date given by Haynes could be about right. This is based on depictions of the trees in the topographical views above. It is also possible that rather than being later than the Woodlands Plan, it is in fact earlier.

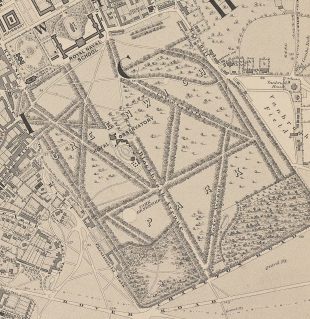

John Rocque's Map, published 1746

An exact survey of the city's of London Westminster ye Borough of Southwark and the country near ten miles round begun in 1741 & ended in 1745 by John Rocque Land Surveyor & engrav'd by Richard Parr. Published 1746 (detail with recent hand colouring)

'An exact survey of the city's of London Westminster ye Borough of Southwark and the country near ten miles round begun in 1741 & ended in 1745 by John Rocque Land Surveyor & engrav'd by Richard Parr.'

Made up of 16 individual sheets it set a new standard for maps of the city and extended from Woolwich in the east to Hampton Court in the west.

Within Greenwich Park, Rocque named just two of the avenues: Love Walk (marked on the Gascoin and Travers Plans as Paul's Walk) and Brazen Face Walk (marked on the Gascoin and Travers Plans as Snow Hill Walk.

A key difference between this Map and the earlier plans is the appearance of a new avenue of trees running from the north east corner of the Park to One Tree Hill. Whether or not it really existed is unclear as the only other plan that shows it was published just a few years later in 1749 in The London Magazine. If it did exist, part of it would have been planted on what is a very steep scarp slope. Also possibly fictitious is the extension beyond Love Walk of the right hand avenue radiating from the rounds at the bottom of the Map and the cluster of five buildings immediately to the south of the Observatory, though it is possible that they were briefly associated with sand and ballast extraction from the hillside to their east.

At the south end of the Park some of the boundaries between the coppices have disappeared. Although Montague House is shown adjacent to the southern part of the western park wall, Park corner House has been omitted on this copy and that held by the National Maritime Museum (Object ID:PBC 5317), but is present on others such as the 1878 photolithographic copy in the National Library of Scotland.

The London Magazine Plan published in March 1749

Detail showing the burial ground and mausoleum, the remains of the dwarf orchard, part of Cross Avenue and the pyramidal conduit house

Engraved on copper, the printed area measures about 25cm x 19cm. Neither the surveyor nor the engraver is named, but we do know from the engraving that the plate was printed for R. Baldwin Junr. at the Rose in Pater Noster Row for The London Magazine. To make everything fit, the engraver has partly cropped the edges of the Park (half the boundary wall is missing on the top, bottom and left edges and missing in its entirety on the right).

Like the Rocque Map, the Plan shows an avenue of trees running from the north east corner of the Park into the slopes of One Tree Hill. Whether this really existed, or whether it was simply copied from Rocque's Map remains unclear. One argument for the Plan having been produced independently is that the possibly fictitious extension beyond Love Walk of the leftt hand avenue radiating from the rounds at the top of the Map that appears on the Rocque Map is not duplicated here.

Unlike the Rocque Map on which it is omitted, The London Magazine Plan shows the burial ground created in 1707 on part of the site of the Dwarf Orchard that had been laid out in the northeast corner of the Park by William Boreman during 1661–2. It seems to be the only plan that does so. More than that, at the southern end of the burial ground, it shows what may be the only surviving image of the Mausoleum that was built under the supervision of Nicholas Hawskmore in 1713–14. It also shows the only known depiction (albeit not very clear) of the pyramidal conduit house once existed at the eastern end of Cross Avenue (just to the north of One Tree Hill), and is the earliest known plan to mark its location.

In 1808–1812, the short lived Royal Naval Asylum Infirmary was built on much of the site of the burial ground. In 1822, it was subdivided for residential use with many of the houses having their own private entrances to the Park. The houses still survive as does the mausoleum in an altered state in one of the gardens. However the widening of the road in 1823 means that the east end of the mausoleum is now next to the pavement. For more information about the burial ground and later buildings on the site see John Bold's Greenwich, an architectural history of the Royal Hospital ... (2000).

The Morton Plan c.1773-1793

Titled 'A map of Greenwich Park by John Morton' and measuring 55.5cm x 53.5 cm, this Plan is drawn on velum using a pen and grey wash. Like the Woodlands Plan, it is a bit of an enigma as it is not known who commissioned it or why. It is also undated.The Plan is held in the collections of the National Maritime Museum and a higher resolution version can be viewed online: Object ID: CMP/31. It came to the Museum in the 1950s, but there is no record of how it was acquired or any earlier provenance.

The dates given above are based on the drawing of the Observatory and the plan view of the Observatory buildings. Bradley's extensions to the Observatory are shown, as are the 1773 alterations to the Summer House, but seemingly not the sash windows installed in the Octagon Room by the Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne in about 1790. Curiously, most of the chimneys are also missing.

One possibility is that the Plan was drawn for Maskelyne or someone associated with the Royal Observatory. There are three reasons for wondering this. The first is the drawing of the Observatory at the bottom. The second, and perhaps the more telling, is the orientation of the Park which is unique amongst the plans. It has been drawn so that the northern boundary of the Observatory is horizontal. The third is that the Observatory is the only structure within the Park that is labelled apart from One Tree Hill. Despite its apparent splendour, the Plan lacks numerous other details. but does mark the relatively short lived pyramidal conduit house that was erected at the eastern end of Cross Avenue.

The Morris Plan of the Parish of St Alphage from about 1834

Detail from the Morris Plan showing the Park. Reproduced by permission of the Greenwich Heritage Centre (see below)

'A PLAN of the PARISH OF ST. ALPHAGE, GREENWICH in the county of KENT. From an actual survey by W.R. MORRIS.'

this Plan is thought to date from 1834 and was completed at a time of rapid change in the neighbourhood of Greenwich Park. St Mary’s Church in its north-west corner was completed in 1825, construction having begun in 1823, whilst the extent of the Observatory grounds suggests that the Plan was completed before the site was expanded in 1837.

No direct evidence has been found as to why the Plan was commissioned, but one possibility is that it was related to the passing of the 1834 Poor Law.

Whatever the reason for the Plan being made, the accurate portrayal of the trees in the Park does not seem to have been a priority as all the avenues tend to be shown as single rows of trees. It is the earliest Plan that has been identified that shows the removal of the rounds adjacent to the Blackheath Gate along with the southern end of the western of the two diagonal avenues that had previously radiated from it, the loss of the avenue being due to the annexing of part of the Park for the Park Ranger in 1806 when Montague House became the official residence.

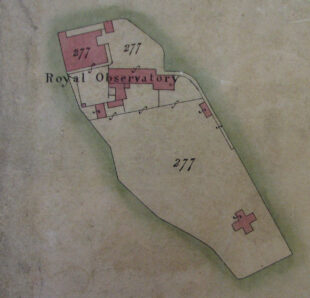

The Tithe Map of 1838

The Observatory site as depicted on the Tithe Map. It includes the Magnetic Ground and extension to the Lower Garden that were authorised in 1837 (Work 16/126). The absence of features surrounding the site is a reflection of the map's purpose. Reproduced by permission of the Greenwich Heritage Centre

'Tithes were originally a tax which required one tenth of all agricultural produce to be paid annually to support the local church and clergy. After the Reformation much land passed from the Church to lay owners who inherited entitlement to receive tithes, along with the land.

By the early 19th century tithe payment in kind seemed a very out-of-date practice, while payment of tithes per se became unpopular, against a background of industrialisation, religious dissent and agricultural depression. The 1836 Tithe Commutation Act required tithes in kind to be converted to more convenient monetary payments called tithe rentcharge. The Tithe Survey was established to find out which areas were subject to tithes, who owned them, how much was payable and to whom.

The primary function of the tithe maps is to provide a graphic index or visual means of reference to the apportionments. Each piece of land liable to tithes was depicted and given a plot number, unique within that parish, by which it could be identified in the apportionment.'

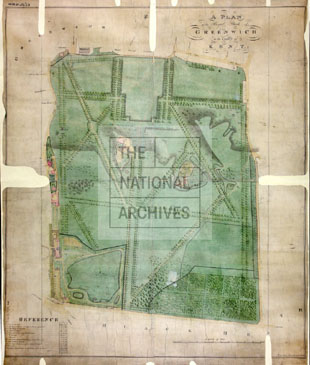

The Greenwich Tithe Map was created in 1838 under the title of The Parish of Greenwich in the County of Kent by the former Observatory Assistant Frederick Walter Simms. It was mapped at a scale of two chains (44 yards) to the inch. A copy is held by Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust (formerly known as the Greenwich Heritage Centre and before that the Greenwich Local History Library). Regrettably, only a small detail showing the Observatory is available for display here. It appears on sheet 19 of 24. Click here to view a transcript of the Tithe Apportionment.

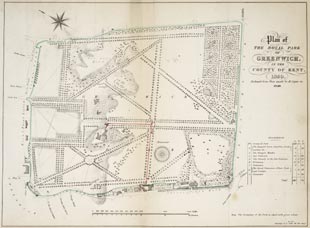

The Sayer Plan of 1840

This manuscript Plan is in the collections of the National Archives (Work 32/23). Drawn at a Scale of 1 inch to 100 feet, the Plan carries the title: 'A PLAN of the Royal Park of GREENWICH in the county of KENT'. It is signed bottom right: 'Henry Sayer, Surveyor, A.D.1840.' Click here to view a larger version.This Plan is possibly the most important of all the eighteenth and nineteenth century plans as it shows far more detail. It is the first Plan of the Park to show the location of the tumuli or barrows in the Anglo-Saxon burial ground near Macartney House, where 34 are marked in total. It is also the first to show the paths that cross the Parterre, the earliest of which are thought to date back to the late seventeenth century.

The Plan has later additions in pencil that someone has subsequently tried to erase - fortunately, not entirely successfully. These include a proposed route of the the extension of the London to Greenwich railway though the Park and also, the location amongst the tumuli of the new reservoir that the Admiralty started building in the 1840s before relocating it to its present location about 170m to the southwest following a public outcry. According to Webster 12 barrows were destroyed during the aborted works.

The tunnel entrance to the ice house is marked but has been mistakenly labelled ' as a conduit. The Plan also marks the 'Standard Reservoir' along with 13 other conduits.

The reduced Sayer Plan of 1848

This version of the Sayer Plan carries the title:'plan OF THE Royal Park OF GREENWICH in the county of Kent.' Plan reduced by George Somers 1848 from map made by H Sayer 1840.

It measures 51cm x 66cm. A copy is kept at the National Archives (Work 32/575). Click here to view a larger version.

Apart from the omission of some of the houses on Crooms Hill, the differences between this and the original 1840 Plan seem entirely cosmetic; the most obvious being the reorientation of the Park so that the Parterre is on the right rather than at the top. As a result, it does not reflect the state of the Park as it existed in 1848.

The Ordnance Survey 12inch to the mile Skeleton Survey Plan, surveyed and engraved 1848–1850

Greenwich Park from the 12-inch Skeleton Survey of 1848–50. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence

'Between 1848 and 1850 [1851?] an initial survey of London at the five-foot to the mile or 1:1,056 scale was undertaken at the instigation of the Metropolitan Commissioners of Sewers, encouraged by Edwin Chadwick and other health campaigners. Chadwick recognised the importance of a large-scale survey of London with accurate height information for planning sewers, even if the maps omitted the range of other detail typically included at this scale for other towns. The 487 sheets covering central London were numbered individually and laid out on the St Paul's meridian. The campaigns of James Wyld II MP against the Ordnance Survey and their work in London successfully limited the detail included on the plans and their derivative scales to outlines. Wyld criticised the expense of the Survey and their use of sappers and miners rather than private surveyors, although this was hardly a detached perspective, given Wyld's own business as a map publisher based in London. A set of 44 plans, reduced from the 'Skeleteon [Skeleton] Survey' to a scale of 12 inches to the mile or 1:5,280 were published.'

The Greenwich sheet (sheet XII.N.W.) was surveyed and engraved 1848-1850 under the direction of Captain Yolland. Click here to view it at a higher resolution on the National Library of Scotland website. Click here to view 42 of the 44 sheets as one seamless layer.

In some ways, the plan of the Park is more informative than it might have been if all the details had been included. What it shows very clearly are not only numerous spot heights and bench marks, but also the routes through the Park that people were actually using. Unlike the Sayer Plan of 1840 and 1848 and the revised Sayer Plan of 1850 which all show a path coming up the centre of the Giant Steps, the Skeleton Plan shows it on the eastern side of the Ascent, something which is corroborated by contemporary images.

Whilst some buildings such as those of Greenwich Hospital are shown, other such as the Royal Hospital School (now the buildings of the National Maritime Museum) are omitted completely. In some cases just the frontages of the buildings are marked. The portrayal of the Observatory itself is interesting as in places the distinction between building and grounds in unclear. The triangles with dots in the centre are triangulation stations used in this or earlier surveys.

Rather curiously, although the pyramidal conduit house (not labelled) is shown along with three other conduits nearby, but none of the others shown on the 1840 Sayer Plan are marked. Also not marked is the boundary of the Park itself.

The Sayer Plan updated to 1850

This version of the Sayer Plan carries the title:'Plan of THE ROYAL PARK OF GREENWICH IN THE COUNTY OF KENT. 1850. Reduced from Plan made by H.Sayer in 1840.',

the lithographer being Standidge & Co. The Boundary of the Park is edged in green. Note the mis-spelling of Crooms in Crooms Hill and Crooms Hill Grove where the C has been replaced with a G.

Unlike the reduced Sayer Plan of 1848, this Plan has also been updated. It has also been reorientated so that the Parterre is now on the left. Unlike the 1848 version in which the trees are all reproduced in the same positions as in the 1840 plan, their depiction in the 1850 Plan seems more schematic and no longer directly reflects those of the two earlier ones. Some of the more obvious differences between the 1850 and the 1840 & 1848 versions are:

- the appearance of the covered reservoir (the large group of concentric circles)

- the absence of the tumuli even though many still existed

- additional buildings within the Observatory grounds

- the disappearance of Keepers Cottage (near the centre of the Park) and its replacement with a new lodge by the Blackheath gates

- the reinstatement of those buildings on Crooms Hill that were included in the 1840 version, but excluded in the 1848 reduction.

One of the two images of Keeper's Cottage that Webster included in his book. It is not clear if the sketch dates from 1750 or 1850. The meaning of the annotation on the right is also unclear

Copies of the Plan exist at both The National Archives (Work 32/691) and the RGO Archives (RGO6/610). The RGO copy has been marked in red to show the route proposed in January 1852 for the installation of underground galvanic cables for the sending of time-signals from the Observatory to the galvanic telegraph of the South Eastern Railway (which was along Blackheath Avenue turning right into the Great Cross Avenue and out of the Park via the path between The White House and Macartney House and ultimately across Blackheath to Lewisham Station).

The Weller Map, first published Sunday 13 October 1861

The sheet from which this Plan is taken forms part of a set of maps of London that were published in installments in the Weekly Dispatch in the early 1860s, this particular one being published on 13 October 1861. It was later republished in 1863 in the Dispatch Atlas. Click here to view the complete sheet.Rather curiously, although the Blackeath Gates are marked, no point of entry into the Park is shown at this point. Just two avenues are named: Blackheath Avenue and Lovers Walk. Although other contemporary plans show that tree lined avenues shown in the 1850 Sayer Plan were still largely intact, several have been ommited on this Plan which appears only to be showing those that have an obvious path along them suggesting that parts of it were copied from the 1848–50 Ordnance Survey Plan which probably explains the reason for the incorrectly orientated eastern Terrace Walk.

Stanford's Library Map of London, sheet 16, published 15 February 1862

Greenwich Park from Stanford's Library Map of London and its Suburbs, Sheet 16, (15 February 1862). Reproduced courtesy of Yale University Library

Coming just 12 years after the 1850 version of the Sayer Plan, the Stanford Plan has a couple of apparent anomalies. The first is the marking of the Giant Steps (the first time they have appeared on a plan since the early eighteenth century) and the second is the Terrace Walk on the eastern side of the Parterre which is shown with a spurious kink in it. Whilst the Giant Steps may have been repaired (more research is required), the kinked Terrace Walk appears to be a draftsman's error in which the avenue of trees has been mistakenly drawn on either side of part of a path that ran across the parterre and is clearly visible on the Sayer Plans. This particular path is thought to have been eliminated around the mid 1890s. No changes appear to have been made to the Park in the 1872 edition of the map.

The Park from a survey completed by the Ordnance Survey in 1867

Greenwich Park as surveyed in 1867 Detail from an Ordnance Survey 6-inch map. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence

At the 1:1056 (five feet to the mile) scale, the Park is spread across five separate sheets, of which only three can currently (2025) be viewed online.

1:1056: London (Cos. Middlesex and Kent) Sheet XII.12

1:1056: London (Co. Kent western division) Sheet XII.22

1:1056: London (Co. Kent western division) Sheet XII.32

At the 1:2500 (approximately 25 inches to the mile) scale, the Park is spread across two sheets:

At the 1:10560 (6 inches to the mile) scale, the whole Park appears on just one sheet. However, unlike at the other scales, there are two different sheets on which it appears:

1:10560, Middlesex Sheet XXIII

At all three scales, the rounds are labeled by the Blackheath Gates despite the fact that the trees themselves appear to no longer exist and the last map on which they appear is the Morton Plan of 1773-93. This raises the interesting question of what map or source the Ordnance Survey referred to for the name especially as the 1840 Sayer Plan appears to have been the one that was used by the Royal Parks.

On a more general note, even at the largest scale (1:1056) it is unclear to what extent the placing of the tree symbols is schematic and to what extent they reflect the actual location of the trees. This is because the placing of the fir trees on the edges of the Grand Ascent (the Giant Steps) does not correspond with any of the contemporary images of which there are several. As the trees on the edges of the Giant Steps matured, they began to obstruct the view of London from the top of the Ascent. It was possibly for this reason that the trees towards the middle of the western row had been felled by 1840 and not been replaced by the time of the survey. The 1840 Sayer Plan (though not those of 1848 and 1850) appears to reflect the position more accurately. It is also worth noting that the distribution of trees is depicted differently depending on which scale map is being viewed.

This set of plans is the first to show a new short avenue of trees in the north-west corner of the Park running parallel to Maze Hill (clearer on the 1:2500 plan). It is also the first to show the zig-zag path created in 1855? (check Work 16/125) that once ran in an easterly direction up the hill towards the Western Summer House of the Observatory. Also of interest is the entrance to the ice house by the Observatory. It is only labeled on the 1:2500 plan where it has been mistakenly marked as a reservoir.

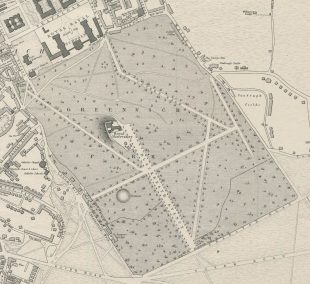

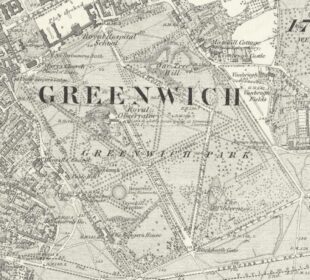

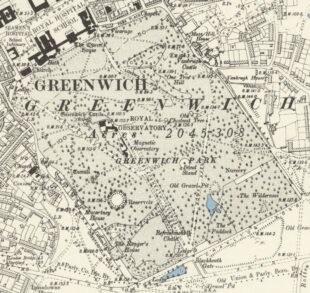

The Ordnance Survey maps revised and re-surveyed in 1893-4

The Park as resurveyed in 1893–94. Detail from the Ordnance Survey 25-inch maps (merged view from two sheets). Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence

Detail from the Ordnance Survey 6-inch map: revised and resurveyed 1893-94. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence

At the 1:2500 scale, the Park is spread across two sheets

At the 1:10560 scale, the whole Park appears on just one sheet. As with the 1867 survey, the Park appears on two different 1:10560 scale sheets:

The Great Cross Walk shown of the Travers Plan of 1697 is today known as Great Cross Avenue. The same cannot be said of Snow Hill Walk, which on John Rocques map of 1746 is labelled Brazen Face Walk and is now known as The Avenue. When the name changes took place is unclear, but it was clearly being called The Avenue by 1867 as this is how it is labelled on the Ordnance Survey maps from that time (above). What seems rather curious is that those same maps label a previously unlabelled avenue of trees to the south of The Avenue as 'Snowhill Avenue'. Why this happened is not yet known.

In January 1894, when making various suggestions to the Ordnance Survey about changes that might be introduced in future editions of their maps, the Bailiff of the Park recommended the removal of the label Snowhill Avenue, not because it was wrong historically, but because 'The trees here are nearly all gone, and there is no appearance of an avenue' (Work 16/127). This wish, along with others was granted. Also removed was the label 'Reservoir' that had been previously mistakenly applied to the ice house.

The 1913 Ordnance Survey 1:2500 Park Plan

During William Christie's tenure as Astronomer Royal, many new Observatory buildings were constructed and others altered. Between 1885 and 1911 the Admiralty (who funded the Observatory) published a series of five site plans at a scale of 66 feet = 1 inch, each being an updated version of the one before. Dated: 1885 (RGO7/50), 1891(WORK16/139), 1896 (WORK 16/139 & 16/1823), c.1905 (WORK17/369) and 1911 (WORK16/637), they all appear to derive from large scale town plans published by the Ordnance Survey, though only that of 1911 actually states that it was prepared and printed by the Ordnance Survey Office.This Plan of the whole of Greenwich Park appears to be in much the same mould. Dated 1913, it was produced by the Ordnance Survey. Unlike the Observatory plans which were published for internal use, the Park Plan was also on sale to the general public.

Click here to view a larger pdf version on the Royal Parks website. This particular copy was used to show the location of all the bombs that dropped on the Park during the Second World War, some of which caused damage to the Observatory buildings.

Following the anarchist bomb incident of 1894, the zig-zag path up to the Observatory where the bomb exploded was removed and much of the ground on the hillside to the north and west of the Observatory fenced off. These works are thought to have been completed during 1896, as the 7 December 1895 edition of The Daily News, carried the following report:

'The funds which the importunity of Mr. Herbert Gladstone obtained from Parliament for the much-needed improvement of Greenwich Park have been in process of rapid expenditure this autumn, and there appears to be every reason to believe that the coming summer will find an immense improvement at two distant points in this beautiful old pleasure ground. About 500l. [£500] is being spent on a grand reformation of the slopes of Observatory Hill, which for very many years has been sadly disfigured by the much-abused freedom of scrambling about it hitherto conceded to the visitors to the park. There is to be no more of this liberty to do mischief. An immense quantity of earth has been deposited on the hillside to replace that which incessant scuffling about it has worn away, and which the rains have washed down, and the work will soon be in readiness for extensive planting of shrubs and other things naturally arranged. The whole hillside has been railed in, the zig-zag path up to the summit having been abolished. This, of course, is not the pathway leading up to the Observatory gates, which remains, and from the top of which a broad terrace affording a magnificent view will lead round the Observatory at the summit of the replanted slopes. This work is sufficiently advanced to render it tolerably sure thạt the spring will find it completed if the weather should prove at all favourable. ...'

The Plan is the first of the large scale Ordnance Survey plans to show the Christie Enclosure in the Park. It shows both the original Magnetic Pavilion erected in the centre in 1899. It also shows the Magnetograph House which was not completed until 1914. Interestingly, the location show is not where it was actually built but directly to the north of the Magnetic Pavilion. Further research is required to establish if this was the location originally planed or if it is a mapping error.

Also making an appearance for the first time are the mens' urinals at the bottom of the hill to the west of the Observatory. They are thought to date from 1904? (check Work 16/146) and appear to have been demolished in the mid 1960s, when a new set of public lavatories were opened in one of the former Observatory Buildings (the Lower Store) at the south end of the Observatory site.

Detail from the Ordnance Survey 6-inch map, revised 1914 etc. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence

The 1:2500 Ordnance Survey Plan, revised 1914, levelling revised 1915, boundaries revised 1919

At the 1:2500 scale, the Park is spread across two sheets:

Unlike the 1:2500 1913 plan the 1:2500 mapping does not mark as many bench marks. Nor does it label the public toilets by the Blackheath Gates, though it does show all five of the drinking fountains. The distribution of trees is broadly similar, but is different in places possibly be due to them having being felled.

At the 1:10560 (6-inches to the mile) scale, the whole Park appears on just one sheet.

1:10560, London Sheets X, & XI

Note the appearance of contour lines for the first time.

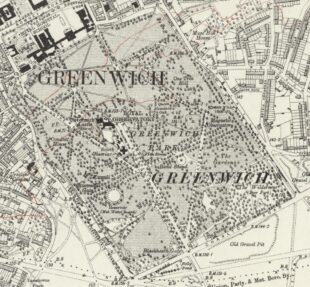

The 1:1250 and 1:2500 Ordnance Survey Sheets, surveyed between 1949 & 1951

The Park as depicted by the Ordnance Survey 1:2500 maps (merged view from four sheets). Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence

TQ3976NE (Apr 1949, rev. Jun 1950)

Merged view of the first 8 of the 1:1250 sheets

At around the same time, the Ordnance Survey produced a series of 1:2500 sheets. Four cover the Park:

Merged view of the four 1:2500 sheets

When looking at the merged view, a number of inconsistencies in the mapping become very obvious. These include the fact that the size of symbols used for the trees varies from sheet to sheet and that the slope of the southern part of the covered reservoir is marked in a different way to the northern half. The size of the symbols used to represent the paths also varies.

On closer examination, it would appear that the two sheets marked with an asterisk were produced by a direct reduction of the component 1:1250 sheets, whilst the other two were redrawn from the master survey. A comparison of the other two (sheets 1 & 4) with the equivalent 1:1250 sheets shows many differences including the location of some trees having been altered as has the number of steps leading northwards from the Observatory store (now the Park toilets).

Interestingly, one thing that is shown on all the 1:2500 sheets but not the 1:1250 ones are plot numbers and acerages, suggesting that the two produced by a direct reduction must have had the additional information added either before or after the reduction took place. There is also an elongated S symbol that appears numerous times on paths and elsewhere on the reduced sheets that do not appear on the original versions.

Acknowlegements

Many thanks to the National Library of Scotland for making so many Ordnance Survey maps available under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence. Links to individual maps are given in the sections above.

The images from the British Museum are reproduced under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license, courtesy of the The Trustees of the British Museum. All have been further compressed for this website. MG.718 has also been reduced in size. Museum Number: 1880,1113.5519 consists of two plates that have been digitally joined and cropped. Museum number:

Notes:

1. Park Corner House, Sale: (source)

'Evening Post' No. 192, 1–4 March, 1728–29, advertises: 'To be Sold at Auction At Daniel's Coffee-house in Lombard-street on Tuesday March 11, 1728–29—A Messuage or Tenement, called PARK-CORNER House, situate upon the Corner of Greenwich Park Wall on Blackheath ... Printed particulars ... are deliver'd Gratis at ... Temple Exchange Coffee-house in Fleet-street. ...'

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan