…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

Clock errors and the regulation, rating and comparison of the pendulum clocks at Greenwich (1675–1957)

Page under construction

It is suggested that this page is read in conjunction with:

The astronomical basis of timekeeping

Until the introduction of atomic time in 1967, the rotating Earth and the length of the day were the basis of our timekeeping system. When the Observatory was founded precision timekeeping was still very much in its infancy. It had long been known that natural days varied slightly in length and that the difference between apparent and mean solar time varied during the course of the year. Many astronomers also believed that the Earth was rotating at a steady rate (i.e, that it was isochronal) – but nobody had yet be able to show it, not least because prior to the invention of the pendulum clock by Christiaan Huygens in 1656, nobody had a sufficiently accurate timekeeper to do so.

The difference between apparent and mean solar time is today known as the equation of time. In Flamsteed's era, it was sometimes referred to as the equation(s) of natural(l) day(e)s. In 1672, three years before he became Astronomer Royal and before he even owned a clock, Flamsteed wrote a paper on the equation of time – De temporio aequatione diatriba. It first appeared in 1673 as an appendix to John Wallis's Jeremiae Horrocci opera poshuma (which was reprinted in a different order in 1678).

One of Flamsteed's first investigations at Greenwich was to check if the Earth was indeed iscochronal. By 1678, with the help of a fixed telescope with which to observe the dog star Sirius that he had set up in 1677 and a pair of specially designed clocks set to show mean solar time, he had been able to satisfy himself that it was. Somewhat surprisingly Flamsteed did not publish a paper announcing his findings. It also seems surprising today that from the time of the Observatory's founding in 1675 until his death in 1719, instead of sidereal time, Flamsteed used mean solar time and/or apparent solar time for all his observations including those that he made with his mural instruments – a practice that was discontinued by his successors (apart from Halley?).

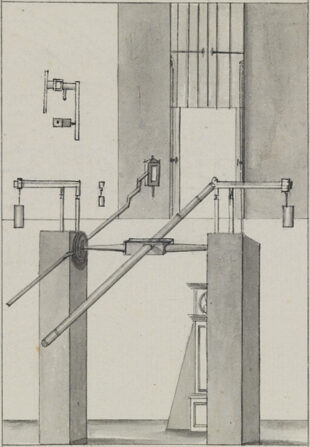

Bradley's 8-foot Transit Instrument with the Transit Clock Graham 3 in the late 1700s. Detail from a drawing of Astronomical Instruments by John Charnock. © National Maritime Museum, Object ID: PAF2956 (see below)

One of the disadvantages of using the transit clock as the sidereal standard was that it had to be mounted in close proximity to the transit telescope which meant it was being continuously subjected to a wide range of atmospheric conditions.

The installation of a chronograph in 1854 paved the way for a clock mounted in a more stable environment to be referenced to the observations made with the transit telescope. The first of these came into use in 1871. Although the Airy Transit Circle was in use fom 1851 until 1954 in 1927 it stopped being used for time determinations in favour of one of the Small Transit Telescopes originally been purchased for the British 1874 Transit of Venus expeditions - the improved accuracy of the observations being due to the fact that unlike the Transit Circle, the Small Transits were reversible in their mountings.

By the early 1900s, many astronomers had become convinced that the Earth was slowing down. An analysis of the Greenwich lunar observations made since 1750 allowed an estimate to be made of the rate of slowing (estimated at the time to be of the order of one millisecond a day per century, whilst the increased precision in the observations that could be made with the combination of Small Transit Telescope and the Shortt Free Pendulum Clocks (the first of which was acquired in 1924) began to allow short-term fluctuations in the rate to be both detected and measured.

In 1937, the use of a single clock as the sidereal standard for the Observatory was abandoned in favour of taking the mean of all the serviceable Shortt clocks at Greenwich (the time on the mean solar clocks being converted to sidereal time for the purpose). These five were supplemented by another Shortt Clock housed at the National Physical Laboratory at Teddington (NPL) and later one from the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh as well, time signals from which were being received on a regular basis at Greenwich.

In 1939 the observatory obtained its first quartz clock. Soon after, it and other quartz clocks elsewhere were added to the group of Shortt Clocks in time determinations. By 1942, it was clear that Quartz clocks would eventually replace pendulum clocks as the Observatory's standard timekeeper.

Always showing the wrong time!

From an astronomer's point of view, the key requirement of a good pendulum clock was not that it should show show the correct time but that is should have a steady rate (i.e. didn't slow down or speed up of its own accord), so that its rate of gaining or loosing did not change over time. Although in practice, such a clock could not be made, the transit clock was always one of superior performance.

At Greenwich (as in other observatories) the transit clock very rarely showed the correct time. The important thing was to get it adjusted so that its rate (i.e. how much it gained or lost each day) was typically less than two seconds a day (usually less). No attempt was made to fine tune the clock so that it neither gained nor lost as the clock's error and hence the rate at which it was gaining or losing was easily determined from the observations of the clock stars.

Once the error was approaching a minute (sometimes two minutes or more) the clock would be stopped briefly and the hands adjusted to about the correct time. At this point, if the rate was large, adjustments might also be made to the pendulum (slightly shortening it for example would cause it to speed up). The reason for not allowing the error to become too large was because of the danger of misreading and therefore misrecording the time shown by the minute hand.

The pendulum clocks used as the Observatory's sidereal standard (1750–1957)

The table below shows the clocks used as the sidereal standard until the pendulum clocks were superseded by Quartz clocks. Until 1871, there was no separate standard clock as the Transit Clock performed this function.

Date |

Clock |

TransitClock? |

||

| 1750 | – 1821, Sep 10 | Graham 3 | ✓ | |

| 1821, Sep 10 | – 1822, Nov 24 | Molyneux and Cope | ✓ | |

| 1822, Nov 24 | – 1822, Nov 28 | Hardy* & journeyman clock combination | ✓ | |

| 1828, Nov 28 | – 1823, Mar 02 | Johnson (presumed to be Grimaldi & Johnson) | ✓ | |

| 1823, Mar 02 | – 1823, Mar 12 | A clock loaned by Kater | ✓ | |

| 1823, Mar 12 | – 1823, Nov 04 | Molyneux and Cope | ✓ | |

| 1823, Nov 04 | – 1871, Aug 21 | Hardy | ✓ | |

| 1871, Aug 21 | – 1922, Oct 24 | Dent 1906 | X | |

| 1922, Oct 24 | – 1925, Jan 01 | Cottingham | X | |

| 1925, Jan 01 | – 1937 | Shortt 3 | X | |

| 1937 | – c.1944 | Mean of the Shortt clocks from Greenwich & elsewhere | X | |

| 1944 | Pendulum clocks largely superceeded quartz clocks | X |

* At this point in time, Hardy was in use in the adjacent room with the Mural Circle so a journeyman clock (described by Pond as a Counter) was set to beat in time with it.

From time to time, other clocks were substituted when the standard clock was out of service for repairs or modification. Whilst Pond used a clock of Dent's own while the Transit Clock Hardy was being altered in 1830, it appears that this was the only time that another clock was substituted for Hardy during the whole of Pond's tenure, suggesting he was rather averse to the concept of a reserve Transit Clock. Airy had no such qualms, making use of Graham 1, Graham 2 and Arnold 2 in the period 1836–1850. In later years after the Transit Clock ceased to be the standard clock, both Dent 2 and Shortt 11 were used as the reserve sidereal standard at different times, Shortt 11 replacing Shortt 3 for over a year (including the whole of 1934) on one occasion. The clock mentioned here are just examples. For a full list of clocks that were substituted all the daily observations from 1750 onwards would need to be examined together with the various reports that were issued. Relevant extracts from the reports from 1836 onwards .

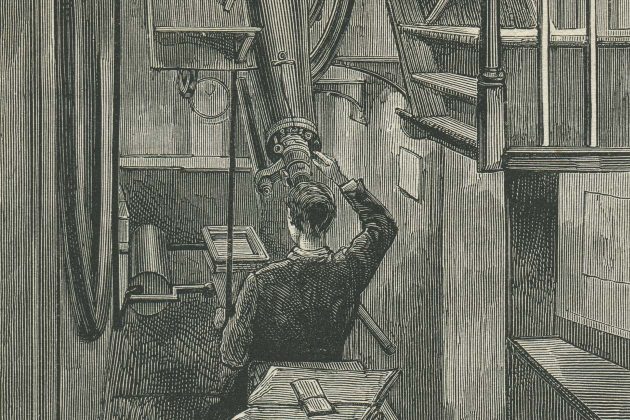

Hardy in use with the Airy Transit Circle. The observer is in a pit below the level of the floor. The dial can be seen towards the top left. From the 8 August 1885 edition of The Graphic (detail)

The Transit Telescopes used for time determinations at Greenwich (1750–1957)

Date |

Telescope |

|

| 1750–1816 | Bradley's 8-foot Transit Instrument | |

| 1816–1850 | Troughton's 10-foot Transit Instrument1 | |

| 1851–1927 | Airy Transit Circle2 | |

| 1927–1957 | One or other of Small Transits B, C or D3 |

1. Troughton's 10-foot Transit Instrument was erected in the same location as Bradley's 8-foot Transit but on heightened piers.

2. The Airy Transit Circle was erected in a room adjacent to that which housed the 10-foot Transit Instrument.

3. A full breakdown of which telescope was used when can be found with the description of the Small Transits using the above link. During WW2, observations from a small transit instrument at Abinger and a reversible transit circle at Edinburgh also made a contribution. During and after the war and until the move to Herstmonceux, the time department's main base was at Abinger. From 1947 onwards, a Bamberg Broken Transit Instrument was the main instrument used there.

Procedures adopted by Flamsteed (1675–1719)

Flamsteed made the great majority of his published observations in three distinct locations: the Octagon Room (1676-1719), the Sextant House (1676-1690), and the Quadrant (Arc) House (1690-1719). He may also have made a small number of observations of solar eclipses in the eastern Summer House (and possibly the western one). He also made a few attempts to observe from the bottom of the Well Telescope (not published) and with his long refractors from the roof of Flamsteed House and the garden. The Octagon Room, the Sextant House and the Quadrant (Arc) House were each equipped with their own clock or clocks in the case of the Octagon Room. Flamsteed also had a portable clock.

Rather than each location having its own observing book, the observations were simply recorded chronologically into a single volume, new volumes being started as and when needed. Although he recorded the time of each observation, Flamsteed did not record where in the Observatory the observation was made or the clock that he used. When he came to publish his observations, those from different locations remained lumped together in chronological order, again without any mention of clock or location. Although it is often possible to distinguish observations made with the long refractors in the Octagon Room from those made elsewhere with the equatorial sextant or mural arc because the tube length is normally but not always recorded and because of the subject being observed, it is not possible to discern from which of the two Octagon Room clocks the recorded time was taken though this would not matter if Flamsteed always took the time from the same one if they were syncronised (which seems unlikely). Flamsteed seems to have 'corrected' (ie deduced the errors) of the clock he was using in the Octagon Room from measurements of the Sun's altitudes (more on this later). However, not all such observations were made there as it the preface to the Historia (Volume 3) records that he made similar measurements in the Quadrant house during the commissioning of the Mural Arc. He may also have made further such observations there in later years. Likewise, the published observations and correspondence show that Flamsteed used a projection screen to view a solar eclipse on at least six occasions but there is no explicit record of whether these observations were made in the Octagon Room or in one of the Summer Houses. For more information see: Solar eclipses observed at Greenwich during the time of Flamsteed (1675–1719).

Famsteed's observations were published in Latin in two editions. The first, Historiae Coelestis Libri Duo, appeared in 1712. The story of how it came to be published is both complex, and acrimonious and resulted in Flamsteed having a lifelong feud with both Halley and Newton. Flamsteed thoroughly disapproved of it. Following the death of Queen Anne in 1714 and Newton’s patron, the Earl of Halifax, in 1715, he was able to acquire 300 of the 400 copies that had been printed. After extracting those pages of which he approved for reuse in a new edition (those that had been printed before the end of 1707), apart from a few copies, he burnt the rest.

The second edition was published posthumously in three volumes in 1725:

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 1

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 2

Historia Coelestis Britannica Volume 3

Things however are not straight forward. The first volume contains observation made between 1676 and 1689 while the equatorial sextant was the main observing instrument. The second contains those made between 1689 and 1720 when with the Mural Arc was the main instrument in use. However, the way in which Flamsteed presents his observations changes between the two volumes. In Volume 2, the observations are published in the order that they appear in the observing books. In Volume 1, they are divided into six categories (which makes comparison with the observing books a lot more time consuming). The categories are:

- Distances of fixed stars (1676–1689)

- Observations of comets & primary planets (1676–1689)

- Observations of the Moon's approach to fixed stars (1676–1689)

- Observations of the configurations & eclipses of the Jovian comets (1676–1689)

- Observations of sunspots (1676–1689)

- Observations of altitudes & distances of the sun from the top quadrants (observations of refraction) (1678–1681)

The distance of the fixed stars are further rearranged in chronolgical order by constelation. No explanation is given for the change in presntation. Nor does Flamsteed explicitly explain how he rated his clocks or deduced their errors. Nor did he publish tables of their rate or error, though it is possible (though unlikely) that such tables exist and are waiting to be discovered in the archives.

The clock times in both the 1712 and 1725 Historias are given in terms of the astronomical day, with each day beginning and ending at midday (rather than the civil day which ran from midnight to midnight and started 12 hours earlier). It is important to note too that all Flamsteed's clocks (apart from the unsuccessful Degree Clock) were set to mean solar time rather than sidereal time. Despite the fact that the observations as published in the Historias were given based on the astronomical day, Flamsteed only started using astronomical time in the observing books (RGO1/4-8) when the mural arc came into use in 1689. The times recorded in Flamsteed's first three observing books (RGO1/1-3) were recorded in terms of the civil day using a 12 hour rather than 24 hour notation. Civil time was also the time system used for eclipse observations in Philosophical Transactions where some of Flamsteed's observations were later published.

The following terms are used in the column headings of the various sets of observations in the Historias (some sets just one, others two):

| 1 | Temp App. / Temp Ap. | Apparent time |

| 2 | Tempora per Horologium Oscillatorium | Time by the pendulum clock |

| 3 | Tempora ex Altitud. Correcta | Times corrected by altitude(s) [of the Sun] |

| 4 | Tempora ab Observationibus Correcta | Times corrected by observations |

| 5 | Tempora Correcta | Corrected times |

| 6 | Tempora (inde) ab Observationibus Correcta | Times corrected (from) observations |

| 7 | Tempora vera Apparentia | True apparent times |

Some of the observations and notes in the observing books are recorded in English and some in Latin. Not all the manuscript observations appear in the printed Historias. One example of those omitted were the third set of observations of the Sun's altitude that he took for correcting the clock at the time of the solar eclipse of 1676 (the three sets of observations having been taken on 31 May and the 1 June. It should be noted here that there is also an unexplained discrepancy in these particular sets of altitude observations in the observing book and those subsequently published in the Historia and Philosophical Transactions, which also differ from one another. Other examples of observations of the sun's altitude being omitted from the Historia have also been found. Also omitted, are the observations of Sirius made with with the Sirius Telescope in the late 1670s.

The Sextant House Clock (where Flamsteed made most of his observations prior to the arrival of his Mural Arc in 1689) was made by Thomas Tompion in 1675. Prior to being placed in the Sextant House, it was used for a few months in the Octagon Room while the clocks for that room were under construction. The first recorded observations at the Observatory are of the eclipse of 1676, June 11 (June 1 old style civil, May 31 old style astronomical). Details of the clock are scantly. It had a one-second pendulum, but possibly no maintaining power (this is based on a record in Flamsteed's observing Book RGO1/1 that it lost 8 seconds when it was wound on 9 October 1676).

Two year going clocks made by Tompion with 13-foot (four-metre) two-second pendulums (the Great Clocks) were installed in the Octagon Room in the summer of 1676 (probably on 7 July) and were in proper working order for the first time by 24 September. They can be seen to the left of the door in the etching below. Although at first sight, the clocks appear identical, a key difference was in the way the pendulums were suspended. The one closest to the window was suspended from a spring whilst that nearest the door was pivoted on a knife edge. Both were set to show mean solar time, with one presumably acting as a check on the other. One thing we don't know is to what extent they may have interfered with one another (something that Huygens had previously observed in his own clocks and written about in 1673 in his book Horologium Oscillatorium). However, as Flamsteed's pendulums were long and the arc through which they swung was small, any such interference was likely to be undetectable. A third clock with a shorter pendulum (and seemingly designed to show sidereal time) was also planned for the Octagon Room though there are no obvious records of it having been used in practice.

In 1690, Flamsteed bought a new clock for use with the Mural Arc which first came into use at the end of 1689 and was mounted in the former Quadrant House. Like the Sextant House Clock, it had a seconds pendulum. Little else is known about the clock which was probably made by Tompion.

As well as the clocks already mentioned, Flamsteed had a clock made by Tompion in 1691 with a 2/3 second pendulum that was designed to show sidereal time in terms of degrees minutes and seconds rather than in terms of hours minutes and seconds. Now referred to as the Degree Clock, there appear to be virtually no manuscript records (and no published records) of this clock ever being used.

We also know that Flamsteed had a portable clock or horologium ambulatorium. Little is know about the clock, but it does appear in one of the Francis Place etchings of the Observatory produced in about 1677. There, it is shown in the eastern summerhouse where it would presumably have been used to time solar eclipses. It was presumably also used when timings were required with one of the outside telescopes. Presumably spring driven It was probably only wound when needed for observing and would most likely have been set by comparing it to one of the clocks in the Octagon Room. There are sporadic references to it in the original observing books (RGO1/1-8). There are also occasional references in the observing books to a horologium supra and a horologium infra which were presumably alternative names Flamsteed used for two of the clocks already mentioned (one of the Great Room Clocks and the Sextant House Clock?).

All this presents a problem when trying to find the observations from which Flamsteed obtained the rate and hence the errors of his clocks. There are occasional references to comparisons between the the Sextant House and Octagon Room Clock in the first volume of Flamsteed's observing book (RGO1/1). How they were made is not stated but it was presumably by means of his portable clock or a watch.

We can be pretty sure that to start with at least, Flamsteed determined the errors and rate of the clocks used in the Octagon Room clocks by making equal altitude observations of the Sun. By 1678 however he also had the means to determine their error and rate from observations made with the Sirius Telescope. But did he?

Likewise, the errors and rate of the mural arc clock could easily have been determined from observations of selected stars as they crossed the meridian. But an examination of the observations shows that he probably determined them by applying the equation of time to timings of the Sun as it crossed the meridian.

Little serious research has been done into Flamsteed's methods of recording and structuring his observations since Derek Howse's time in the 1960s and early 1970s. Since that time, All the known correspondence of Flamsteed has been published. A proper examination of this in parallel with the manuscript and published observations (both in the Historias and elsewhere) together with the manuscript copies of Flamsteed's observations and calculations is now long overdue.

Of the seven clocks owned by Flamsteed, only three survive: the two great clocks (both of which have been modified from their original form and the Degree Clock.

Procedures adopted by Halley (1720–1742)

Procedures adopted by Bradley prior to the 1750 re-equipping of the Observatory (1742–1750)

Procedures adopted by Bradley and Bliss (1750–1764)

An inspection of the manuscript observations of Bradley indicates that from its arrival as the new transit clock in 1750, Graham 3 was normally wound along with the other two month going clocks by Graham on the first day of the month. The manuscript observations also show that at the time of winding, the difference between Graham 3 and one of both of the other Graham clocks was also noted. By 1755, Bradley was using a shorthand code to record this. None of this information about winding or comparing the clocks was transcribed into the first volume of Bradley's published observations, which covered the Transit Observations made between 1750 and the end of 1755, but it was patchily transcribed into the second. In the preface to the second volume (which covers the Transit Observations made between 1756 and 1765 by both Bradley and Bliss), the code was explained as follows:

'That the reader may fully understand some remarks, it may be necessary to inform him, that N. stands for the new Clock in the Transit Room [Graham 3], Q. for the Clock in the Quadrant Room [Graham 2], and G. for the Clock in the Great Room [Graham 1]. When the times by any two of these are compared, the comparison is expressed thus, N. Q. 4", meaning that the Transit Clock was 4" before the Quadrant Clock.'

An example from May 1763 can be seen here. No explanation was given however as to how the clocks were compared. However, given their proximity, it may have been possible to hear the beat of the Quadrant Room Clock in the Transit Room (and vice-versa). Given that the comparisons were only given to the nearest second, it is also possible that if two observers were available, one could be looking at the Transit Room Clock whilst the other called the time in turn from the Quadrant Room and Octagon Room Clocks. In the case of the Octagon Room Clock this would have required the windows of both rooms to be open.

Procedures adopted by Maskelyne and Pond (1765–1835)

Maskelyne (who arrived as Astronomer Royal in 1765) continued to normally wind the clocks on the first day of the month. In the preface to his first volume of Observations:he explained his method of comparing the transit clock with that in the Great Room (the Octagon Room):

'In the year 1766, two assistant clocks, with a loud beat, were provided, and set up; one in the transit room and the other in the great room; principally designed to be used in windy weather, when the beats of the other clocks could not be well heard at a distance: in which case the assistant clock was first set to beat exactly with the principal or astronomical clock. Moreover, by the help of the bell of the assistant clock, which rings exactly every minute, when the second-hand comes to 60, and which may be heard from the great room to the transit room, when a window in each is left open, the astronomical clocks standing in these rooms are readily compared together, and their difference noted, in order to reduce the observations made in the great room to the time of the transit clock.'

In later years, other methods were used to compare the clocks especially in Airy's time (more on this below). Prior to this, in 1825, (while Pond was Astronomer Royal) William Hardy was given a 30 guinea by award by The Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce for his invention, some years earlier, of an Instrument for measuring small intervals of time. The records show that by 1828, one was in use at the Observatory when it was used to compare the Transit Clock (Hardy) with the clock Graham 3 (which was set to mean solar time) by Sabine in the write up of his pendulum experiments as follows:

'The comparison of the clock [Graham 3] with the Greenwich transit clock [Hardy] was effected by means of a machine constructed by HARDY for the purpose, it being capable of indicating 0".05 in time; and from the mean of 5 comparisons which was always employed, it is hoped the comparisons never err 0.03 from the truth; these comparisons were made at or near the time the observations were making for the rate of the transit clock, on the accurate determination of which must rest the accuracy of the rate of the clock used in the experiment.' (Phil Trans (1829))

How the comparison was actually made was unfortunately not explained in the paper by Sabine, nor has any information yet been found that has been written by Pond. The instrument survives in the collections of the National Maritime Museum (Object ID: ZBA0668)

Information on how the transit clock was rated appears just once in the published observations of Maskelyne and not at all in those of Pond. Maskelyne's observations were published in four volumes and between them cover the years 1765–1810. Only the first (published in 1776) includes a preface. On page iii Maskelyne gives the following information:

'The Observations made with the transit instrument are the most numerous of any; besides the transits of the planets, the transits of several fixed stars being observed every day that the weather permits, to be compared with those of the planets, in order to settle their right ascensions, and serving also to determine the clock's rate of going from day to day. The stars commonly made use of for these purposes are those contained in the Tenth of the annexed Tables: which, as they lie near the Equator, move with greater velocity over the Meridian than stars of greater declinations, and they are moreover sufficiently bright to be easily seen in the day-time, when the air is clear, and not liable to be obscured by a small haziness of the air, or the thinner sort of clouds, either by day or night, as smaller stars would be. …

In making computations from the Observations, I deduce the daily rate of the going of the transit clock, from a mean of the differences of transits of the same star at the same wire on different days; in doing of which I make equal use of all the wires. …' Read more.

A somewhat clearer explanation is given by Robert Woodhouse, the Lucasian Professor of Astronomy at Cambridge. In Volume 1 of his A treatise on Astronomy, Theoretical and Practical (1821) he describes the process as follows:

'The practical method of determining the clock's daily rate, that is, its gain or loss during two successive transits of a star, is to subtract the mean meridional passages of certain stars on one day (as shewn by the clock) from the passages of the same stars on the next, or on some following day. The sum of the differences divided by the number of days intervening between the observations, and by the number of stars, is the clock's mean daily rate; to which quotient, or result, should the clock gain, the sign + is affixed; should it lose, the sign -.'

He then goes on to give a practical example based on Maskelyne's observations made with Graham 3 on 23 & 25 January 1798 and the observations made with the same clock by Pond on 6, 7 & 8 August 1816. Although it had no impact on the methodology, it should be pointed out that not only did Woodhouse made transcription errors when copying the data (for example, the Pond observations were actually made on 5, 7 & 8 August), but he also failed to notice that Pond or his Assistants had made an error in one of the calculations of the clock's rate – an error which he then repeated. When using a transit telescope and clock to measure right ascensions, there are further complications due to instrumental errors. As well as discussing these in his Treatise, Woodhouse also discussed them in his 1825 paper: Some Account of the Transit Instrument Made by Mr. Dollond, and Lately Put up at the Cambridge Observatory.

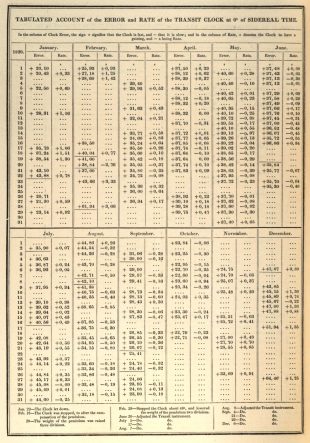

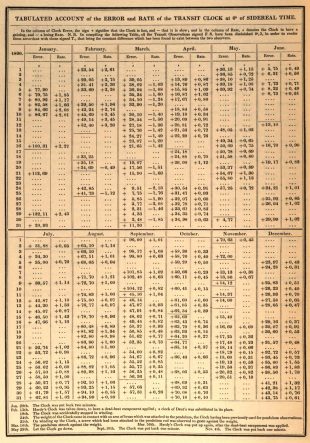

Interestingly, the rate of the Greenwich transit clock as computed from individual 'clock' stars only began to be included in Maskelyne's published observations part way though volume 3 at the start of 1793. To aid the reader, the number of days that had elapsed since the star had been last observed, was also recorded in the column headed 'No. of days. The practice of including the daily rate was continued by Pond. In 1831, he also began publishing the error of the clock alonside its rate. Meanwhile, back in 1829, he had also begun publishing on a single sheet, a table showing the error and rate of the clock at 0h sidereal time at different points throughout the year. Two are reproduced in the section below. How these rates were computed from the figures given in the transit observations is not stated.

Tabulated account of the error and rate of the Transit Clock in 1829. Digitized by Google from the 1829 volume of Greenwich Observations at the University of Princeton

Tabulated account of the error and rate of the Transit Clock in 1830. Digitized by Google from the 1830 volume of Greenwich Observations at the University of Princeton

Meanwhile, in 1828 Pond's Assistant Thomas Glanville Taylor had supplied information about the rate of Hardy to Edward Sabine who was carrying out experiments at the Observatory on invariable pendulums. Sabine's paper, which was published in Philosophical Transactions the following year, included the actual calculations Taylor made to determine the rate. Based on groups of stars of similar right ascensions, the composite figures differ significantly from the figures of the daily rates based on individual stars that were subsequenly published in Greenwich Observations.

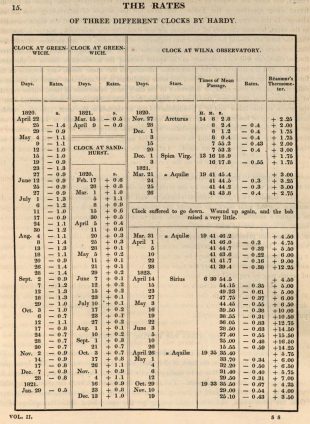

William Pearson's table comparing the rates of three different Hardy regulators. From Vol. 2 of his Introduction to practical astronomy. Digitised by Google from the copy in New York Public Library

Procedures adopted by Airy (1835-1881)

Unlike his predecessors, Airy had all the Observatory clocks wound weekly on a Monday, irrespective of how long they were designed to run for. This remained the case until 1864 when, the transit clock (Hardy) began to be wound twice a week on Mondays and Thursday. The reason for these changes is not recorded. The second however may have occured as the result of a seemingly unrecorded alteration to the driving weight and associated pulley system.

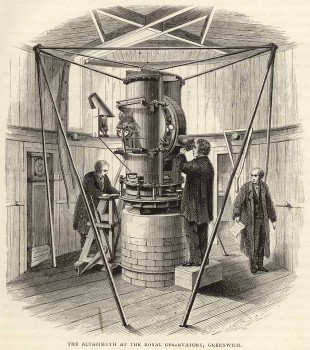

Airy's Altazimuth Telescope. The clock Graham 1, which was initially used to time the observations, can be seen in the alcove in the left. First published in an article by Edwin Dunkin in the 1862 volume of The Leisure Hour, the image was later reprinted in the 1891 edition of Dunkin's The Midnight Sky. Probably based on the image first published by Airy in 1847, the inclusion of the three figures helps gives the instrument a sense of scale

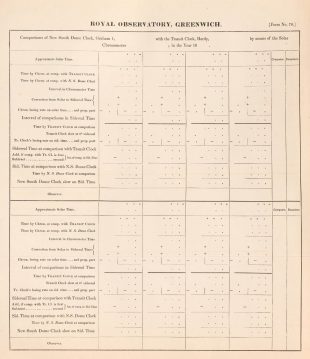

This form was produced by Airy in the late 1840s for comparing the sidereal time shown by the Graham 1 with the sidereal time shown by the Transit Clock Hardy, by means of a Solar Chronometer. The introduction of the chronograph in 1854 allowed most observations of transits taken with the Altazimuth to be timed directly with Hardy without the need for such a comparison to be made (see below). Specimen copy of Form No. 70 from the 1845 volume of Greenwich Observations (published in 1847). Reproduced courtesy of Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek under a No Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Only license (see below)

One of the necessary steps in the process of reducing the observations was to standardise the times shown by the two clocks. The process was described by Airy in the 1847 volume of Greenwich Observations as follows:

'The comparisons of the Transit Clock [Hardy] and the Clock of the New South Dome used with the Altitude and Azimuth Instrument (Graham 1) are made by means of a solar chronometer (Parkinson and Frodsham 1826), the chronometer is brought close to each of the clocks, and the time of accurate coincidence of beats is noted ; the chronometer-intervals between the comparisons, which is sensibly Solar Time, is converted into Sidereal Time; and the sidereal time at the comparison with the transit-clock, being found by correcting the transit-clock-time for error and rate of the transit-clock, the sidereal time at the comparison with the New South Dome Clock is found, and thus the Error of that Clock is ascertained. From the successive Errors, rates of the Clock are deduced, and the Errors applicable to the observations, and which are given in the sections of Azimuth and Zenith Distance, are computed.'

The same method of was used to compare Graham 1 with Hardy throughout the working life of the telescope, though the actual solar chronometer (which always showed mean solar time) varied. The same technique was presumably used with the other sidereal clocks in the Observatory when the times recorded on them needed to be referred back to Hardy.

1854: The introduction of a chronograph and the subsequent alterations made to Hardy

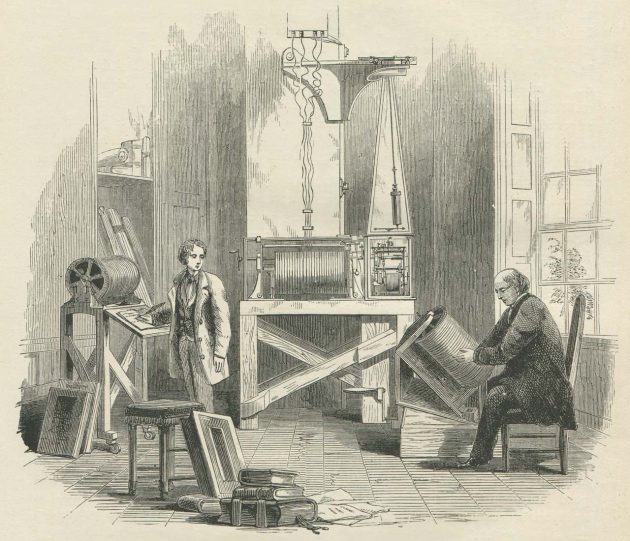

In the early 1850s, a chronograph was installed at the Observatory. Its primary purpose was to record the time of transit of a star by electromechanical means at the press of a switch by the person at the eyepiece of the telescope. Its introduction dispensed with the need to make eye and ear observations except in a few well-defined circumstances. Although its planning began in 1849, it was not in a properly functioning state until 1854. Before looking at how Hardy was altered to provide it with electrical impulses at one second intervals, it is helpful to know more about how the chronograph worked. Airy provided a detailed account of its construction in the 1856 volume of Greenwich Observations. He also provided a brief description in the introductions to Greenwich Observations from 1854 onwards. In his series of articles in the Leisure Hour in 1862, his Assistant Edwin Dunkin used this as the basis of a more basic description:

'Before describing the recording apparatus, it is necessary, however, to state that the original method of observing transits consists in counting the beats of a clock, and estimating the fraction of a second when the object passed one of the wires in the telescope. The clock-time is then entered into the observer's book, the operation being repeated as many times as the number of wires. The new method of observation, or the chronographic method, is much more simple when the registering apparatus is in good working order.

The chronographic recording apparatus is placed in the ground floor of the north dome [i.e. the eastern summerhouse]. The clock, which is of peculiar construction, the motion being governed by the conical rotation of a pendulum, gives a sensibly uniform motion to a revolving brass barrel, which is in connection with it. The barrel is covered with woollen cloth, upon which a sheet of paper is folded, the ends of the paper being gummed together. A spindle which is attached to the clock turns two long screws, causing a travelling frame to traverse the whole length of the barrel. This frame carries two levers, each armed at one end with a pricking point, mounted in such a way that, when the opposite end of the lever is pulled away from the barrel, the pricking end is pushed against it, and makes a permanent puncture on the paper. Two galvanic magnets are fixed on the travelling frame, so as to attract the lever ends opposite to the pricking points. All that is required, therefore, to cause those points to make punctures upon the paper, is to send galvanic currents through the magnets.

One of the prickers is devoted to the registration of the seconds of the clock in the transit-circle room, the communication being made by wires connecting the clock with the travelling frame. The other pricker is used for the registration of the times of observation when a star passes behind a wire in the telescope, a similar communication with wires being made. For the proper generation of the galvanic force, a voltaic battery is included in the circuit of each course of wires.

On this recording instrument, therefore, nearly all transits observed with the transit-circle, altazimuth, or great equatorial, are permanently registered. They are extracted from the sheets, and converted into figures on the following morning-an operation requiring care, but which, in skilled readers, is not considered a very difficult proceeding.'

Looking northwards in the Chronograph Room. The chronograph is standing on the table in the centre, its conical pendulum being independently supported by a bracket attached to the telescope pier. The person on the right appears to be loading a new recording sheet onto the drum, whilst the one on the left appears to be transcribing the results from another. Originally published in the 1862 volume of The Leisure Hour, the image was later reused in the 1891 edition of Dunkin's The Midnight Sky, which is where this copy comes from

'The Barrel-Apparatus for the American method of Transits has been practically brought into use: not, however, without a succession of difficulties, arising sometimes from causes very hard to discover. When the instrument was approaching to a serviceable state, there still remained an imperfection in the ill-defined form of the punctures on the paper. At this juncture, Lieutenant Maury, U.S.N., paid me a brief visit, and in the course of inspection of the instruments he alluded to this very defect, and to the method which had been used in America for its remedy. Although my apparatus did not admit of the same application, yet, possessed of the principle, I had no difficulty in embodying it in a form adapted to my wants; the prickers were mounted on springs, and now the punctures are perfectly round. The paper on which the punctures are to be made is folded in a wet state, upon a brass cylinder covered with a single thickness of tailor's woollen cloth, and has its edges united by glue.

The punctures, it will be remembered, are produced by two systems of prickers, which have nothing in common except that they are carried by the same travelling frame, which moves slowly in the direction of the barrel-axis while the barrel revolves beneath it. These require separate notice.

One pricker is driven by a galvanic magnet whose galvanic circuit is completed at every second of sidereal time. It was at first intended by me that the completion of the circuit should be effected by the same smooth-motion clock (regulated by a conical pendulum) which drives the barrel. I found, however, that I could not ensure such a constancy in the radial arc of the pendulum as would make its rate sufficiently uniform to entitle it to be considered as the fundamental clock; and, moreover, there was a little difficulty in referring its indications to those of the transit-clock (which must be used in some cases). I, therefore, carried wires from the pricker-magnet to the transit-clock, connected there with springs whose contact is made at every second by the transit-clock. At first, the contact was made by the touch of a pin fixed in the pendulum-rod; and this construction for a time answered well. But it so happens that, in our transit-clock, the pendulum is carried by one frame, and the point of attachment of the galvanic springs by a different frame: it was impossible to maintain these in steady adjustment; and the rate of the clock was sensibly disturbed. I have now adopted the following construction, which promises to succeed better. A wheel of 60 teeth is fixed on the escape-wheel-axis, and the teeth of this wheel in succession make momentary contacts of the galvanic springs.

The position of the springs is so adjusted that the effort of the wheel-tooth upon them occurs only when one escape-tooth has passed the sloping surface of the pallet, and the other escape-tooth is dropping upon its bearing; and thus the resistance of the springs does in no way affect the legitimate action of the train upon the pendulum.

The other pricker is driven by a galvanic magnet, whose circuit is completed by an arbitrary touch- made by an observer's finger upon a contact-piece. Of contact-pieces there are three. One is upon the eye-end of the Transit Circle: it effects the contact of two brass rings which (by means of wires passing in the interior of the tubes) are connected with two other brass rings surrounding the axis and touched respectively by two springs on the pier leading to the galvanic wires. The other two contact-pieces are upon the rotating base-plate of the Altazimuth (one to be used with Vertical Face to the Right, the other with Vertical Face to the Left); the parts which they bring together carry springs which touch two large horizontal rings on the fixed base; and these rings are connected with branches of the same pair of wires which communicate with the Altazimuth. Thus Altazimuth observations are referred absolutely to the same time-record as Transit-Circle observations.

It is necessary to mark upon the revolving barrel the beginnings of some minutes and the numeration of some hours and minutes. This is done by arbitrary punctures given by the observer's touch, upon a simple system which scarcely merits detailed description.

In order to guide the eye through the multitude of dots upon the sheet, lines of ink are traced by means of a glass pen, which is attached to the same frame as that by which the prickers are carried. ...

... I have only to add that this apparatus is now generally efficient. It is troublesome in use; consuming much time in the galvanic preparations, the preparation of the paper, and the translation of the puncture-indications into figures. But among the observers who use it there is but one opinion on its astronomical merits – that, in freedom from personal equation and in general accuracy, it is very far superior to the observation by eye and ear.'

The final alteration took place in 1856. Although significant, Airy did not report it to the Board.

‘The opportunity was taken of the Transit-Clock being removed for repair in the month of November 1856, to have one of the teeth in the wheel before mentioned cut away, so that once in each minute no contact of the two springs takes place. The omission of the corresponding puncture on the revolving barrel thus marks with certainty the commencement of each minute.’ Intro to Greenwich Obs 1856

The timing of the various alterations to Hardy (as extracted from the volumes of published observations to which links are given) was as follows:

Date |

||

| 1853 | Chronograph installed | |

| 1853, Dec | Galvanic wires connected to Hardy's pendulum on Nov 10, but removed on Nov 11. (Link) | |

| 1854, Jan 6 | 'An apparatus was attached to the pendulum of the Transit-Clock, for the purpose of closing a galvanic circuit in the middle of each oscillation'. (Link) |

|

| 1854, Feb | Removed for cleaning on Feb 17 and returned on Feb 23, Mudge and Dutton used in the meantime. (Link) |

|

| 1854, Apr 11 | Taken down and Graham substituted (which one not specified). (Link) |

|

| 1854, Apr 12 | Taken down and Mudge 'temporarily set up'. This would suggest that either the Apr 11 entry was incorrect (though it does not appear to have been corrected in the errata lists published in the succeeding years) or Graham was only used for a few minutes prior to Mudge being set up (Link) |

|

| 1854, May 15 | Hardy brought back into use. Airy records: 'To the clock is attached a supplementary wheel with sixty teeth, on the prolongation of the Axis of the scape wheel, so that at every beat of the clock one of the teeth presses upon the upper of two springs a, and closes the galvanic circuit'. (Link) |

|

| 1855, Jul 11–14 | Clock out of action while galvanic contact springs altered. (Link) | |

| 1856, Nov 18 | Dismounted on November 18 for cleaning and Mudge and Dutton used in its stead. (Link) | |

| 1856, Nov 24 | Remounted. While being cleaned, Airy took the opportunity to have one of the teeth in the wheel cut away, so that once in each minute no mark was placed on the chronograph drum. (Link) |

The arival of Dent 1906 as the new sidereal standard

Designed by the Astronomer Royal, George Airy and ordered in 1869 from E. Dent & Co., Dent 1906 was mounted in May 1871 and succeeded the transit clock Hardy as the sidereal standard when it was brought into use on 21 August 1871. In his 1872 Report to the Board of Visitors, Airy said of the new clock: ‘This clock was constructed, under my direction, ... , and may be regarded, I think, as an excellent specimen of horology.’ The perfomance was such, that it was possible to detect changes in its rate that were attributable to changes in atmospheric pressure. When he designed the clock, Airy had hoped to to devise a barometric compensation device, but at that time, was unable to come up with a satisfactory way of doing so. To start with, changes in the rate due to changes in atmospheric pressure were normally allowed for in the calculations; but in the autumn of 1873, with the aid of Thomas Buckney, one of the partners at E. Dent & Co, a physical compensation device was designed and added to the clock.

For the first 40 years of its life, it was located near the photographic barometer on the northern wall in the basement of the Magnetic Observatory. Like the transit clock it replaced, it too was rated from observations made with the Transit Circle, by means of underground wires that connected it to the chronograph. It served as the sidereal standard for a little over 50 years until it was superseded by the new Cottingham Clock on 24 October 1922. It is now in the collections of the National Maritime Museum (Object ID:ZAA0601)

Published records of the rate of the Transit Clock

Bradley Vol 1 Page 116 (Link)

Bradley Vol 2 p 308 & p413 & 414

Maskelyne from 1793 onwards Vol 3

Pond, likewise. From 1831 also recorded the clock's error.

Further Reading

A Catalogue of the Positions (in 1690) of 564 Stars observed by Flamsteed, but not inserted in his British Catalogue, together with some Remarks on Flamsteed's Observations. Francis Baily. Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol 4, p.129-164

The Evidence for Changes in the Rate of Rotation of the Earth and Their Geophysical Consequences, With a Summary and Discussion of the Deviations of the Moon and Sun from Their Gravitational Orbits. Earnest Brown, Transactions of the Astronomical Observatory of Yale University, vol. 3, pp.205-238 (1926)

Richard Towneley and the equation of days; Tony Kito, British Sundial Society Bulletin Volume 13 (ii), pp.60-65, (Jun 2001) (pdf)

The equation of time as shown on sundiails: John Davis, British Sundial Society Bulletin Volume 16 (iv), pp.135-144, (Dec 2003) (pdf)

Acknowledgements

Detail from a drawing of Astronomical Instruments by John Charnock. © National Maritime Museum (Object ID: PAF2956) is taken from the Royal Museums Greenwich website

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan