…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

The South Building (formerly the New Physical Observatory), the Lassell Dome, & the Lower Store

Originally known as the New Physical Building or New Physical Observatory, the South Building was constructed between 1891 and 1899. It incorporates the dome of a short-lived building constructed at the Observatory in the early 1880s to hold the Lassell telescope. The histories of the two buildings are so intertwined, that they are best dealt with together. As their story unfolds, it becomes clear how much less straightforward Christie was as Astronomer Royal than his predecessor Airy. Christie continually moves the goal posts as he seeks to equip the Observatory with large telescopes – telescopes it has to be said, for which there was no pressing need (other than to keep up with Observatories elsewhere).

The earliest known view of the completed New Physical Building. The north wing is on the left and the west wing on the right. Taken from the roof of the Magnetic Observatory, the image was used by Maunder in his book The Royal Observatory Greenwich a glance at its history and its work which was published in 1900. Photo by Charles Craven Lacey, George Rickett Photographic Archive

The building from a slightly lower viewpoint in about 1926�30. The flag pole (right) was erected to support one end of an aerial wire that was stung between it and another pole on the roof of Flamsteed House for the reception of time signals from Paris. From a postcard published by the Royal Observatory, Greenwich

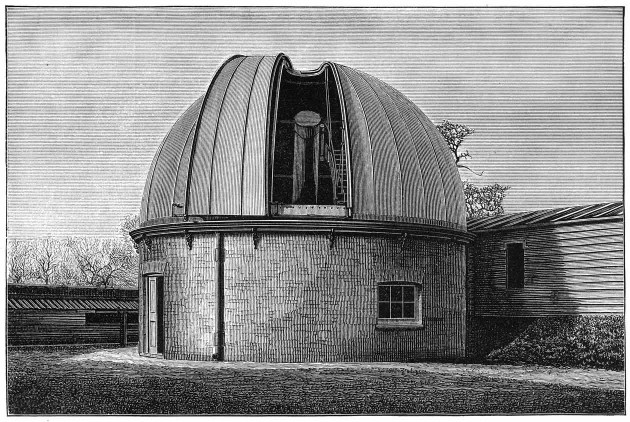

The Lassell Dome

In 1883, a year or so after Christie had taken up the post of Astronomer Royal, the daughters of William Lassell (who had served on the Board of Visitors from 1872 until his death in 1880), offered him their father’s two-foot reflecting telescope – the one with which he had discovered Triton the largest moon of Neptune.

It was accepted without hesitation, necessitating a degree of reorganisation of the magnetic observatory to accommodate it. A single story brick building of 30-foot diameter was erected immediately to the south of, and connecting to Magnetic Office 7. The walls were in place by June 1883. The dome (by T. Cooke and Sons) of papier Mâché on an iron framework was completed in March the following year.

The Lassell Telescope and Dome. The Magnetic Offices to which the Dome was attached are on the right. From: A Handbook of Descriptive and Practical Astronomy, Volume 2, Fourth Edition (London 1890) by George F Chambers

Details of the dome’s constuction

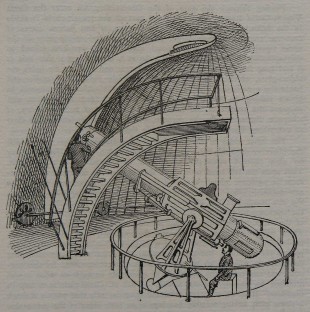

The Lassell Telescope in its dome at Greenwich. Sketched from life by an artist from the Pall Mall Gazette on 27 January 1888 (RGO7/29). The lower of the two observers is looking though the eyepiece of the Corbett 6½-inch refractor which was attached in January 1887 as both a guiding telescope and for the observation of occasional phenomena. Originally published by the Pall Mall Gazette on 30 January 1888, the drawing was reproduced by Cudworth on p.321 of his book: Life and Correspondence of Abraham Sharp (London, 1889)

‘The circular building in which it is contained is situated in the southern part of the grounds, isolated from surrounding buildings. The foundation and the drum upon which the dome rests are of brick. The floor of the observing-room is of asphalt. The height of the room is divided by a platform, inclosed by a railing, at a distance of about 6 feet from the floor. The lower part of the room has large windows and doors, the upper part small windows for light only. A stove is provided.

Dome:- The dome is hemispherical in shape and rests on nine wheels, about 2 feet in diameter, bound solidly to the iron base of the dome and traveling on a flat cast iron circular wall-plate in twelve sections, raised on angle-irons 5 inches above the masonry. Cast in one with this rail is a toothed circle for turning the dome, also in twelve sections, let into the masonry by jogs at the lower part. A single cog-wheel, 3 inches in diameter, gears into the latter circle, the dome being driven by a crank; a larger wheel, 1 foot in diameter, is on the same axle, and the crank may be shifted to this wheel for an increase of power, but that is not at all necessary. The parts of the rail are very carefully fitted and evenly joined. With each of the large wheels on which the dome rotates is one on the same frame, laid horizontally, 9 inches in diameter, to prevent lateral motion, and bearing on the side of the rail on which the large wheels rest or move. The wheels laid horizontally are so adjusted that only those on one side bear at a given instant.

The framing of the dome is of angle-iron, spaced about 2 feet 7, inches apart at the bottom. Besides a heavy circle encompassing the base, there are three lighter circles of angle-iron, laid horizontally, of ¾-inch iron T-shaped, which connect the ribs of the dome. There are two principal frames on the shutter, one on each side, and two intermediate lighter frames and three horizontal braces.

The base of the single shutter travels on two rollers on a light rail on the outside of the dome and its top also runs on a guiding rail. The shutter is moved by a chain (a rope was formerly used, but, being partly exposed, was soon found to become unserviceable) of which both ends are attached to a corner of the base of the shutter and which runs over fixed leading blocks and a movable block, inside and out, for reverse motions. A long-handled lever is used for clamping the shutter in position when closed. The observing-slit extends from a little beyond the zenith to the horizon and is 5¾ feet in clear width at the bottom, 3½ at the top. The curve of the shutter’s surface is struck with a. radius from a center on the other side of the dome and the large frames forming the edges of the slit converge to a point on that side, away from the slit. The edge of the shutter overlaps, when closed, the edge of the slit; a gutter U-shaped is provided at the edge, overlapped by a turned-in edge of r-shaped angle-iron, so that water will not enter, but run off by the gutter. Snow, however, has given trouble; but this can be easily avoided.

The principal feature of the dome is its covering. This is of papier-mâché, put together of sheets arranged to overlap edgewise along a vertical circle of the dome. Perhaps, as Mr. Christie suggested, it would have been better to have had sheets overlapping on horizontal edges, but the appearance at present is better than it would be otherwise. The interior diameter of the dome is between 29 and 30 feet. [...]

The motion of the Lassell dome is remarkably easy, due, first, to its lightness, though the iron frame-work seems almost unnecessarily heavy; second, to the principle adopted of having a series of large wheels traveling on a flat rail, which reduces the friction to a minimum. Apart from this, of course, the dome was carefully designed by Mr. Christie and well built by its constructors, Messrs. T, Cooke & Sons, of York.

The dome, when in use, carries besides its own weight, shutter and the appendages an observing-ladder and the observer. The ladder is fastened to two wooden beams laid horizontally and attached to the frames of the dome and to the following side of the slit, and moves, therefore, with the dome. The latter is easily turned from the ladder by the observer for short. distances, by means of an endless rope passing over leading blocks in proper position overhead and around the Y -shaped ends of the spokes on the wheel carrying the crank for rotating the dome, It can also be turned from the floor. The increase of power before mentioned was dispensed with because the dome turned rather slowly and it could never have been really necessary as now, after the dome has been in use for four years, the power required to move it is very slight.’

Turning the dome – a sports day event!

On Saturday 21 April 1888, the Observatory held a sports day for its staff in the afternoon; a record of the various activities being kept by the Chief Assistant, HH Turner, in his Journal (RGO7/29). The events were more akin to a village fete, than an athletics competition and included a tug of war, an anemometer race, and an event titled ‘Turning the Lassell Dome’. For the latter, each competitor had to rotate the dome once in as short a time as possible. The fasted time was achieved by Turner himself, who managed to turn it in 30 seconds. No references to a sports day have been found for other years, suggesting that the sports day may have been a one-off.

The genesis of the South Building

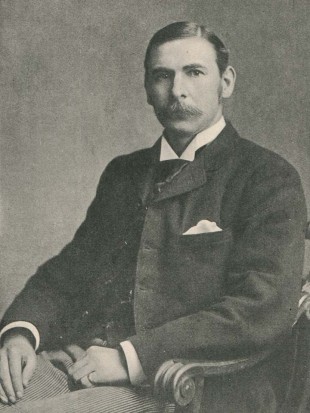

William Christie. This photograph, which is by Elliott & Fry, is one of the best known of Christie. It was used by Maunder in his articles about the Observatory published in the The Leisure Hour in 1898 and then in his follow up book Greenwich Observatory which was published in 1900

‘Owing to want of Space in the Observatory buildings the moveable instruments, clocks and other apparatus which are not in actual use, are for the most part stowed away in their boxes in wooden sheds, where their periodical examination and renovation are attended with great difficulty. For the proper care of these instruments it would be advisable that they should be housed in a brick building to serve as an Observatory museum for instruments and apparatus of scientific value or historical interest. A building of one story, about 40 feet long and 30 feet broad, would be suitable … the proposed building being connected with the circular Lassell building.’

By the following year Christie was able to tell the Visitors that the Admiralty had authorized the building of a storehouse or museum but that it appeared advisable to modify the design. Instead of a single storey building occupying virtually the whole of the ground available for future extensions, he proposed instead to construct a building of two stories with a smaller footprint. This was to have two wings with the Lassell Dome at the centre.

He went on to say that:

‘The effective use of the Lassell telescope for the observation of occultations and phenomena would be greatly increased if it were mounted at a greater height, as it would be if the plan here suggested was carried out’,

complaining

‘that In the present position neighbouring trees interfere greatly with the observations of the Moon and Jupiter when south of the equator, and the use of the instrument is much restricted in consequence.’

This was a somewhat curious thing to be saying, as at the time of the dome’s erection, he had claimed the telescope commanded ‘a nearly unobstructed view of the sky to within 5° of the horizon’.

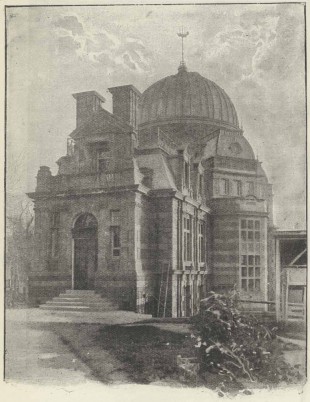

The idea of two wings evolved into three and by early 1891 plans were in place for a cruciform building with four wings, each of three stories, along with a central tower surmounted by the Lassell Dome which together with the Lassell Equatorial were to be moved their from their current position.

The architect employed, was one William Crisp, who came up with an extravagant design reminiscent of the previously fashionable areas in South Kensington that had been developed under the influence of Prince Albert following the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in 1851. As such, it was to be constructed of redbrick incorporating a considerable amount of terracotta decoration.

The downside, of a cruciform building, as was pointed out in 1950 when the building’s future was being considered, was, that the amount of accommodation was totally disproportionate to the amount of structure to be maintained. But the advantage – rather fortuitously since a recession was about to begin – was that it could be built a wing at a time as funding permitted. As things turned out, the building was constructed in four phases over a period of eight years.

The north wing and dome in about 1897. At this point, the east and west wings hadn't been built. From The Leisure Hour (1898)

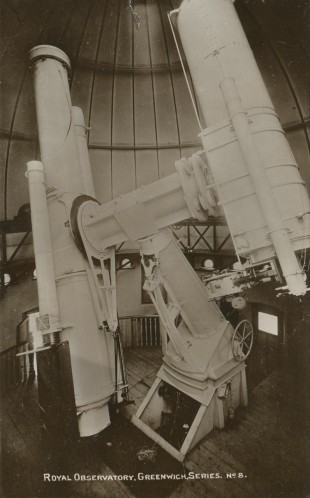

The telescope dome in about 1908: the Thompson 26-inch Refractor is on the left and the 30-inch Reflector on the right. Postcard published by Henry Richardson

Construction begins

First to be built were the lower two stories of the central octagonal tower that was due to house the supporting pillar for the telescope along with the proposed museum. They were commenced in March 1891. Although virtually complete by that June, it took a further year for the glass cases for the museum to be installed. While the work was in progress, the 12.8-inch Merz had been dismounted from the South-East Dome and was being prepared for mounting in place of the 2-foot Reflector on the Lassell Equatorial.

Next to be built was the South Wing, for which a contract was let with Mr H L Holloway, of Union Works, Deptford. Originally, it had been planned to face the building in red brick with dressings of Red Mansfield Stone (a very fine grained, dolomitic sandstone that was pinky red in colour and popular at that time). The contract however specified that the dressings should be of terracotta in order to save money (RGO7/50). Work commenced on 24 November 1892, but by the following March; having reached the first floor, all work came to a halt because of a failure in the supply of terracotta – a problem that was to dog the project at every stage. The wing was finally completed on 20 April 1894. At this point, access between the floors was by means of temporary structures – the permanent staircase not having yet been built.

Meanwhile, construction of the north wing and completion of the central tower and dome, which had been authorised back in 1893, had been put on hold pending the outcome of discussions concerning the gift of £5,000 from Sir Henry Thompson for the purchase of a new telescope. Once a decision had been made to order a 26-inch refractor on a new equatorial mount, and use it with the 12.8-inch Merz as its guiding telescope in the soon to be relocated Lassell Dome, the architectural plans were suitably adjusted and construction of this phase eventually commenced in November 1894, only to be held up by severe frosts and failures in the supply of the terracotta. Before the work on the north wing could commence, the Magnetic Offices which still occupied the site needed to be removed. This was done by rotating the whole range out of the way towards the western boundary. The Lassell Building also needed to be removed – partly because it overlapped the site of the staircase that was about to be built and partly because its dome was required for the new building. It was taken down in August 1895 and re-erected on top of the new tower. But before it was completed, Thompson donated a 30-inch Reflector which was to mounted alongside the 26-inch refractor in lieu of its counterweight, something that reduced the usefulness of both, since only one of them could be utilised at a time. With the exception of the weather vane which was installed in March 1897, this phase of the building works was completed in September 1896. To emphasize the nautical connections, Crisp lit the inside of the dome with a series of circular windows reminiscent of the portholes on a ship, while the weather vane is modelled on the Henri Grace a Dieu, or the Great Harry, a flagship of Henry VIII.

The final phase of building – the construction of the east and the west wings – was sanctioned in 1896, but did not begin until 1897. Following the usual delays in the supply of terracotta they were completed in March 1899. The west wing is built on part of the site originally occupied by the Lassell Dome, whose foundations are almost certainly still preserved beneath it.

The partially completed South Building from the south-east in the summer of 1897. Building of the east wing has yet to start. As a result, the brickwork of the central octagon which was to form its western end can be clearly seen as can the doorways leading to it from the rest of the building. Most of these were sealed pending the wing's completion. The hut on the roof of the south wing was temporary and housed one of the Observatory's photoheliographs. The hut on the ground in front of the building is the 'Great Shed'. This was demolished following the building's completion in 1899. Immediately to its right, a temporary set of wooden steps gave access to the first floor. Photograph reproduced by permission of the Greenwich Heritage Centre (see below). A copy was published in the 17 July 1897 edition of the Illustrated London News

Boundary problems

Once completed the building’s east and west wings broke though the boundary by a few inches, whilst the southern wing went right up to it. This was both detrimental to the appearance of the building and inconvenient in terms of access to the outside spaces. This was not the outcome that Christie had originally envisaged. It had always been his plan to realign the boundary around the building on a give and take basis. No discussions however appear to have taken place until the end of November 1894, when he met with the Bailiff of the Parks (Col. Wheatley) and the Superintendent of Greenwich Park (Mr Jordan) to discuss a proposal of theirs to take over a small part of the western side of the Lower Garden near Flamsteed House. These discussions came to nothing. It seems only to have become apparent that the east and west wings would actually break though the boundary once their construction was underway.

Quite how or why the building came to be positioned so that it protruded marginally beyond the Observatory’s boundaries is unclear. To resolve the situation, it was put to the Treasury Solicitors that ‘In a matter like this which affects two departments of the Government and involves only a slight encroachment’ that the contract for the building works should be allowed to proceed. The Treasury Solicitors subsequently wrote to the First Commissioner of Works (in whose jurisdiction the Park fell) on 17 December 1897, authorising him to settle a new line for the boundary with the Admiralty (WORK16/139).

It took until 1907 for the boundary to be realigned along the lines Christie had originally envisaged – a happy by-product of the enclosure of additional land for the building of the Lower Store (see below).

The building of the Lower Store

Back in 1889, part of the justification for the new building was to improve the storage of the ‘moveable instruments, clocks and other apparatus’, which were not in actual use. Whether the Visitors recalled this in 1906, when Christie was again telling them that a permanent storehouse for portable instruments was required, is not recorded. His proposed solution of enclosing more land and erecting a partly sunk basement on the south-west side of the new building had the benefit of both being relatively cheap and of eliminating two of the points were the South Building either touched or broke through the boundary. The Admiralty agreed the plan and more land was enclosed from the Park, the Royal Warrant authorising the enclosure being issued on 2 November 1907. The store was erected in 1908. With its redbrick and terracotta decoration, it reflects in simpler form, the decorative style of the South Building itself. The date 1908 is set into the sill of the central doorway.

The Lower Store (bottom) and the South Building as seen from the south west in 1933. The projection beneath the top floor window of the south wing (right) contained equipment associated with a spectrohelioscope (an instrument used to study the sun) that was installed in the room behind in 1929

The terracotta decorations

The three designs of the rose, thistle and shamrock motif located above the keystones of the ground floor windows. The above design is present on the east and west wings. Photos: May 2011

Each of the windows on the ground floor (except those on the end of the each wing), has a Tudor Rose above them flanked by a thistle and a shamrock, the three flowers representing the three component countries of the United kingdom – England, Scotland and Ireland. They are of three slightly different designs, corresponding to the three phases in which the wings were built. At the upper levels, the ends of each wing are highly ornate.

The terracotta used in each phase of the building has a slightly different colour. That supplied for the third phase (the north wing and dome) was of such a different colour to the previous phase that a site meeting was held with the manufacturers in May 1894. Judging by the results, there was nothing that could be done. The terracotta supplied for this phase is much pinker than the rest, the contrast being most marked at the join between the north and the west wings. Of different colour again is the 1960s terracotta supplied to repair wartime damage to the balcony over the north entrance and that supplied in 2005 and 2006 when windows were converted into doorways. Unlike the earlier supplies of terracotta, which are all naturally coloured, that of 2005/6 was artificially coloured to match the existing – something it fails to do terribly well.

The names of 24 important figures associated with the finding of longitude and the Greenwich Observatory, are displayed on the cornice above the first floor windows and across two of the chimney stacks. The seven Astronomers Royal who preceded Christie – Flamsteed, Halley, Bradley, Bliss, Maskelyne, Pond and Airy, along with Newton, take the prime positions, at the cardinal and ordinal points. A cast of 16 instrument makers, chronometer makers, clockmakers and others make up the rest. They are arranged in a roughly chronological order in a clockwise direction around the building with Flamsteed taking pride of place above the main entrance. Whilst all the names are accompanied by their year of birth and death, those of the Astronomers Royal (which occupy a greater space) also carry the words ‘born’ and ‘died’.

Name |

Born |

Died |

Attribute |

||

| Horrox | 1619 | 1641 | Astronomer | ||

| Wren | 1632 | 1723 | Astronomer, Architect and founder member of Royal Soc. | ||

N |

Flamsteed | 1646 | 1719 | Astronomer Royal | |

| Sharp | 1653 | 1742 | Instrument maker and Observatory Assistant |

||

| Graham | 1673 | 1751 | Instrument and Clock maker | ||

NE |

Halley | 1656 | 1742 | Astronomer Royal | |

| Bird | 1707 | 1776 | Instrument maker | ||

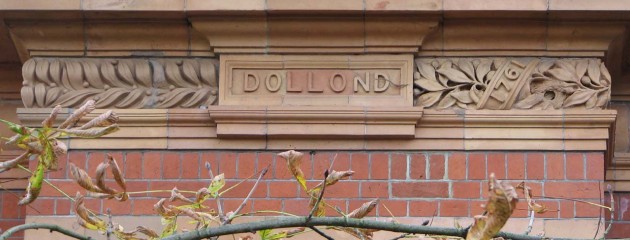

| Dollond | 1706 | 1761 | Lens and instrument maker |

||

E |

Bradley | 1693 | 1762 | Astronomer Royal | |

| Harrison | 1693 | 1776 | Chronometer maker | ||

| Arnold | 1744 | 1799 | Chronometer maker | ||

SE |

Bliss | 1700 | 1764 | Astronomer Royal | |

| Earnshaw | 1749 | 1714 | Chronometer maker | ||

| Herschel | 1738 | 1822 | Astronomer | ||

S |

Maskelyne | 1732 | 1811 | Astronomer Royal | |

| Ramsden | 1735 | 1800 | Instrument maker | ||

| Troughton | 1753 | 1835 | Instrument maker | ||

SW |

Pond | 1767 | 1836 | Astronomer Royal | |

| Simms | 1793 | 1860 | Instrument maker | ||

| Baily | 1774 | 1844 | Astronomer and founder member of Royal Ast. Soc. | ||

W |

Airy | 1801 | 1892 | Astronomer Royal | |

| Sheepshanks | 1794 | 1855 | Astronomer and benefactor | ||

| Adams | 1819 | 1892 | Astronomer (joint discoverer of Neptune) | ||

NW |

Newton | 1642 | 1727 | Astronomer and mathematician (theory of gravity) | |

Three other names are known to have been considered but not ultimately used. They were: Jeremiah Sisson (c.1720–1834), instrument maker, who was ousted out by John Dollond, Thomas Jones (1775–1852), instrument maker, who was replaced by Francis Baily and John Herschel (1792–1871), whose father William was included.

Others who names perhaps should have been considered because their inventions were absolutely essential to the success of the Observatory are Hans Lippershey (1570–1619), who invented the telescope, Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) who invented the pendulum clock, John Napier (1550 –1617) who invented logarithms and William Gascoigne (1612?–1644) who invented the micrometer. An important clock maker who was omitted is Thomas Tompion (1639–1713) who supplied Flamsteed with his clocks and is regarded as the Father of English Clockmaking.

Halley, Newton and Napier as they appear on the old Reference Library in Croydon. From the grouping, it is presumed that the Napier referred to is John of logarithm fame. The image however, seems more like that of General Sir Charles James Napier (1782�1853). Photo November 2017

Also built at the same time was the new building of the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh which was begun in 1892 and completed in 1895. Like the new building at Greenwich, the cornice of the library wing contains the names of various famous astronomers: Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Newton, Herschel, Bessel and Henderson (the last being the first Astronomer Royal for Scotland).

We know from a letter written on 16 October 1890 that some sort of decorative finish had been contemplated at an early stage for the new building at Greenwich (unfortunately, the details are not recorded) RGO7/50. It is not known why Christie and his architect chose to commemorate those associated with the Observatory, but we do know that the scheme had been finalised by 30 November 1892 (RGO7/50). It is possible that they were aware of the plans for Edinburgh, and perhaps Croydon or similar schemes that had commemorated the great and the good elsewhere. One undoubted influence would have been the fact that Flamsteed had never been properly commemorated anywhere and that Christie had just lent his support to a proposal, made public in The Times on 20 August 1892, for a Flamsteed memorial (in the form of a window and a tablet) in the church at Burstow where he was buried. Click here to read more.

Francis Baily was a founding member of the Royal Astronomical Society and its president on four separate occasions. He is most famous for his observations of Baily's Beads which can be seen during a total eclipse of the Sun. The names of Wren, Horrox, Adams, Herschel, Sheepshanks, Simms, Troughton, Ramsden, Bird, Sharp, Graham, Dollond, Earnshaw, Arnold and Harrison are all portrayed in a broadly similar manner. There are however differences between the way they are presented according to which wing they are on. Baily's name is on the west wing. Apart from Dollond, all those on the west and east wings are very similar. On the north and south wings, the foliage on either side of each name all points in the same direction. In addition, those names on the south wing (the earliest of the four) are written in a different font. Photo: March 2011

Troughton's name is on the south wing. Note the shallower angle of the dates as well as the different font. Photo November 2017

Dollond's name runs across the the east wing chimney at the same height as the names above the windows. He is the only person for whom the year of birth has been omitted. A piece of terracotta with a non-matching design has been used as a replacement. Photo November 2017

Halley's name is carried on the NE angle of the building. A similar layout was used for his successors � Bradley, Bliss, Maskelyne, Pond and Airy. Photo November 2017

A bust of Flamsteed sculpted by J Raymond Smith is mounted above the front door on the north wing. The end of the south wing carries the Royal coat of arms and name of the monarch (Queen Victoria). The end of the east wing commemorates the Royal Society and the west wing the Royal Astronomical society.

The gable end of the north wing carries a bust of Flamsteed. Immediatley below him above the door to the balcony is the date MDCCXCV (1895). Immediately below the balcony is Flamsteed's name and the years in which he was born and died. His name is punctuated by an extension of the Keystone which sits above the main entrance. It carries a shield with the dates 1675 (the year Flamsteed was appointed Astronomer Royal) and 1719 (the year in which he died and therefore relinquished the post). Beneath his name, there are two bas-relief roundels. Each is signed Neatby. The one on the right carries the date 1895 and the one on the left 1896. They are thought to represent Athena and Zeus. Photo: June 2009

J Raymond Smith's bust of Flamsteed in the late evening sun. An entry in Christie�s journal for 5 November 1894 (RGO7/30/26) records that � Mr J Raymond Smith, sculptor called to arrange about bust of Flamsteed for N. wing of Physical Observatory and took away ivory medallion and engraved portrait of Flamsteed on loan�. Photo: May 2007

The gable end of the south wing carries the Royal coat of arms and three concealed chimneys flues. The date at the centre is MDCCCXCIII (1893). The words Dieu et mon droit can just be made out between the two scrolls on either side of the shield. Photo: March 2011

The gable end of the west wing carries the Royal Society's coat of arms and the date it was granted its Royal charter (1662). Photo: November 2017

The gable end of the west wing carries the logo of the Royal Astronomical Society and the date of its founding (1820). Photo: April 2008

The logo consists of the motto of Sir William Herschel, its first president: quicquid nitet notandum (whatever shines should be observed) together with an image of his 40-foot telescope. Photo: April 2008

The north west angle of the building carried the original staircase. Neatby sculpted these thee bas-relief panels for the central section of the window. The left panel is signed Dalton & Co. That on the right carries the Neatby's initials WJN and the date 1895. The bat, with outstretched wings (centre panel), is often used in symbolist iconography and is normally associated with death and darkness. Here however, Alastair Scott Anderson, suggests that it represents a creature who like the astronomers has 'vision' at night when others are blind. Photo: March 2008

Astronomia sits at the bottom of the staircase window. It is signed Dalton & Co Lambeth on the left and WJ Neatby Sculp. 1895 on the right. In his journal, Christie records visiting the Doulton Works on 22 March 1895 and discovering that the four signs of the zodiac were the �wrong way� and that the shape of the Moon was wrong and that he arranged for them to be corrected (RGO7/30/31). This photograph suggests that this did not in fact happen. Photo: March 2008

Hidden features

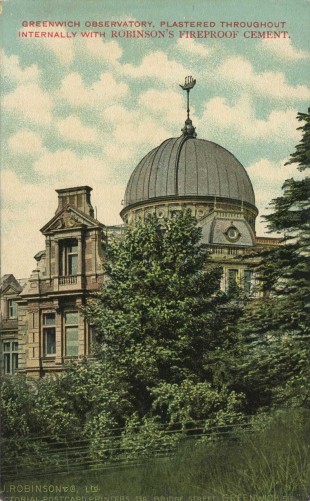

The south wing and dome in 1903 or a couple of years earlier. Postcard advertising Robinson's Fireproof Cement published by J Robinson & Co., Ld. Lithographers, Greenwich. The same image (but without the advertising) was also published as a postcard by Charles Martin

‘The air intake for the hot air heating system in the Main Building being in the stokehole, fumes and dirt from the stokehole were drawn through with the air and ejected into the rooms in the building. To obviate this, a new intake has been built, so that air from outside the building is drawn into the heating chamber. The opportunity was taken, whilst this work was in progress, to overhaul the system and to clean all flues and ducts. The alterations have greatly improved the conditions for the staff working in this building.’

A second more serious problem was discovered in 1950/51 when it was discovered that the furnaces had been feeding carbon monoxide into the rooms due to cracks leading from the flues to the air-ducts. In the same year, the building also suffered a major gas leak.

One of the ground floor heating ducts in 2004. Although the wall ducts remain, those beneath the ground floor were removed during alterations in 2005�7

Getting in and out

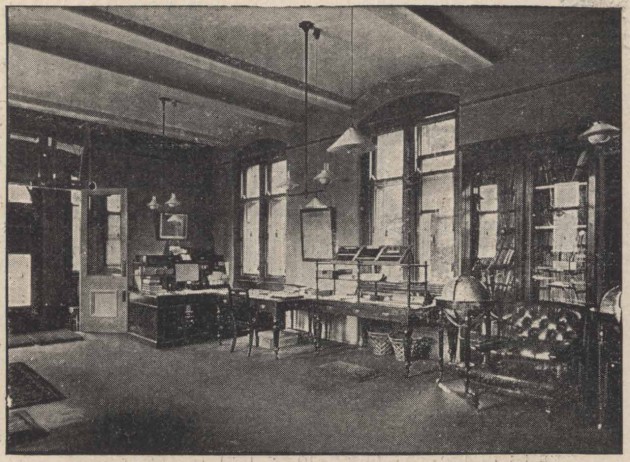

The South Building had no corridors. Internally, all the rooms could be accessed directly from the central octagon. But externally, there were only two ways in. Anyone entering by the front steps would end up in Christie’s office, which since the buildings completion had occupied the whole of the main floor of the north wing. The office was later shared with the Chief Assistants, but in 1902/3 was divided to provide Christie with a separate room at the northern end. The other entrance was a discrete door between the north and west wings at basement level. Above this door the terracotta decoration caries the word staircase. The intriguing question (to which we currently have no answer), is which door did ordinary members of staff use to access the building, and did this change over time?

The telescope pier

An examination of the original plans of the building’s central octagonal tower, reveals an H-shaped pier rising up the centre and a pair of short pier stubs extending into the octagon from the wall on the south side which also rise from the foundations. At the level of the ceiling beneath the dome two arches are shown bridging the gap between the stubs and the two arms of the H of the central pier. These were removed with the rest of the pier during alterations carried out in the early 2000s.

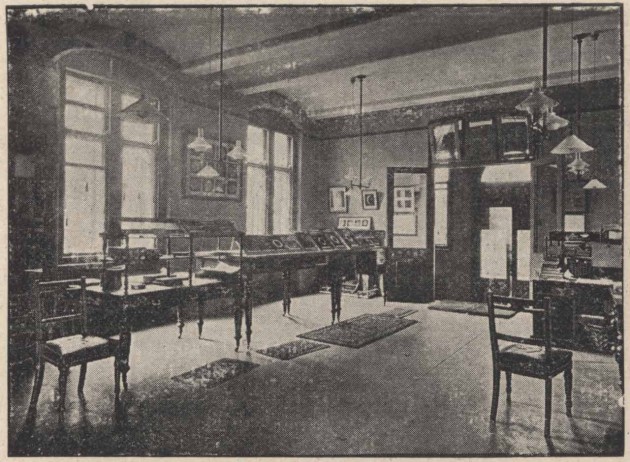

Views of some of the rooms in Christie’s time

The Astronomer Royal's Room looking north-west. The room occupied the main floor of the north wing. The double doors lead out to the entrance lobby. The Astronomer Royals desk can be seen to their right. The fireplace to their left is largely hidden from view by photographs of the solar eclipse which had recently occured on 28 May 1900. From The Graphic (30 June 1900)

Another view of the Astronomer Royal's Room which was taken at the same time, but this time looking towards the north-east. As before, the Astronomer Royal's desk can be seen to the right of the double doors. A second fireplace is hidden from view behind it. From The Graphic (30 June 1900)

A slightly earlier view of the Astronomer Royal's Room, but this time looking towards the doors in the south-east corner leading to the central octagon and the Assistants' Room. Photo by E Walter Maunder. From

By the time this photo was taken (probably around 1902), the two First Assistants were sharing the Astronomer Royal's Room. His desk is in the background. The left hand desk belonged to Philip Cowell and the right hand one to Frank Dyson. In this view, both of the fireplaces are visible. Photograph probably by Philibert Melotte. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) licence courtesy of whatsthatpicture (see below)

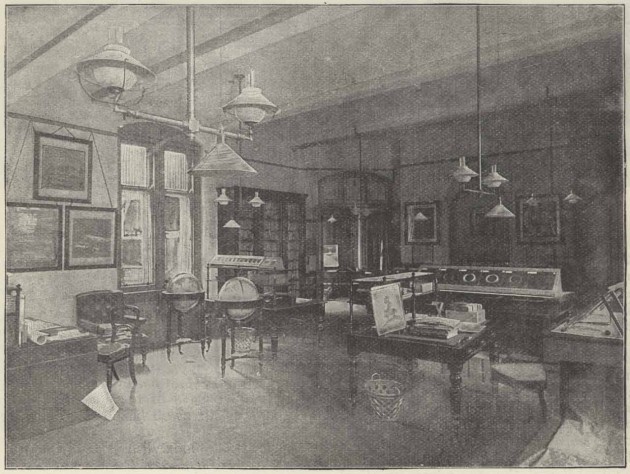

The Assistants' Room in the east wing of the main floor in 1902. Photograph by C Pilkington. From The Graphic (30 August 1902)

"The Astrographic Magazine Staff" in what appears to be the Assistants' Room in about 1902. Photograph probably by Philibert Melotte. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) licence courtesy of whatsthatpicture (see below)

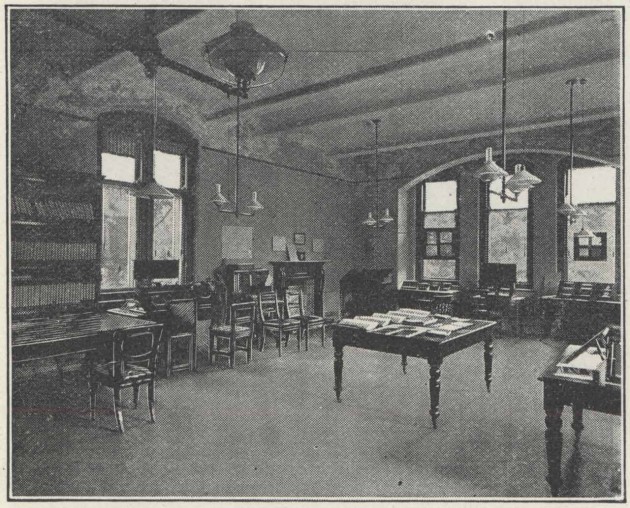

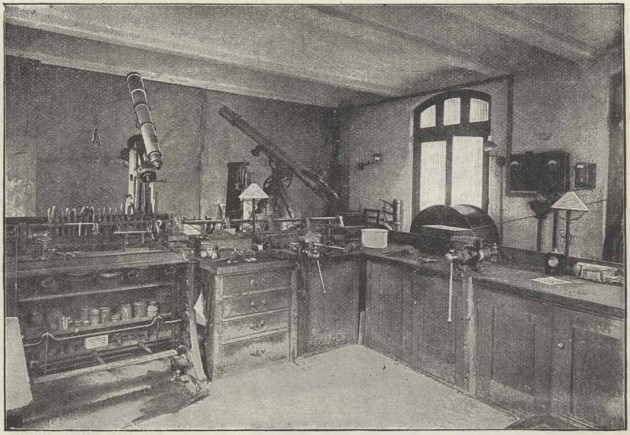

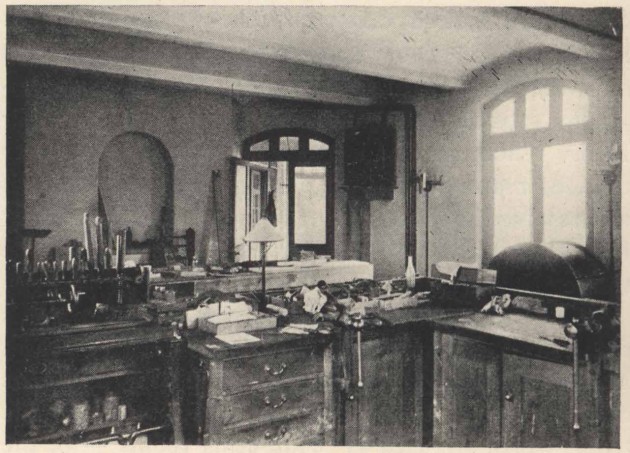

The workshop in the basement of the south wing before the completion of the east wing. Its main occupant until he retired in 1917 was the mechanic GE Nibblet. The view-point is looking towards the north-east. Photo by E Walter Maunder. From The Leisure Hour (1898)

Another view of the workshop from the same direction, but taken a couple of years later. Note the doorway that has been opened up leading into the newly completed east wing. From Maunder's The Royal Observatory Greenwich (London, 1900)

Motorisation of the dome

Originally turned by hand, according to the 1914 Report of the astronomer Royal, two small motors were supplied at some point in the preceding twelve months to turn the dome and to wind the clock weight. This coincided with a switch of electricity supply from the Observatory’s own generator to the local grid.

Scheduled for demolition

With the announcement in 1946 of the impending move to Herstmonceux, consideration was given to the building’s future. In Christie’s view, the building was handsome, but by the late 1940s the consensus among those who held its future in their hands, was rather different. The file held at the Public Records Office is littered with derogatory marks, with the building described variously as ‘in the style of an immense Lyon’s Corner House’ and as ‘in hopeless taste and a disfigurement to the park’. In a report on the buildings future written in 1950, it was stated unequivocally: ‘the architectural style of the building has been universally condemned’ Demolition was recommended, along with a warning … ‘If we are not careful, the museum will wish to retain some of these highly ugly buildings as stores or on some other pretext.’

… to be continued

Further Reading

The South Building, Royal Observatory, Greenwich: The Meeting of Art and Astronomy. Alastair Scott Anderson. Journal of the tiles and architectural ceramics society, volume 12, 2006 pp.31–36.

A British national observatory: the building of the New Physical Observatory at Greenwich, 1889–1898. Rebecca Higgitt. The British Journal for the History of Science, 47(4), 2013 pp.609–635.

The Royal Society’s Coat of Arms. Sir Anthony Wagner. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London Vol. 17, No. 1 (May, 1962), pp. 9–14

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to the Greenwich Heritage Centre for permission to reproduce the 1897 photograph of the partially completed South Building.

The two photos reproduced courtesy of whatsthatpicture are reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) licence. For a link to the original images click here and here.

© 2014 – 2025 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan