…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

The Great storm of 1703

In late 1703, the southern part of Great Britain was battered by a great storm that raged for several days with the strongest winds and most severe damage occurring on the night of 26–27 November. It is thought to be the most damaging to have occurred in southern Britain since the Observatory's foundation in 1675.

Damage to the Royal Observatory

At the Observatory, the three chimneys of Flamsteed House were all blown down and many of the windows damaged. The one piece of good news however was that by falling onto the flat roof, the weight of the western chimneys prevented the lead covering from being ripped off in the gale.

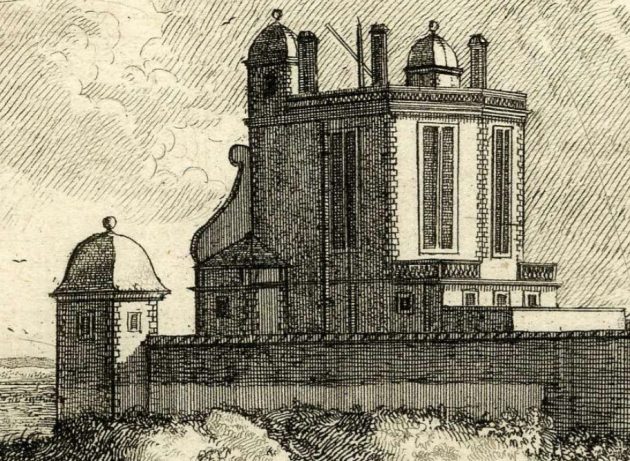

Flamsteed House from the south-west in about 1677. During the storm, the chimney on the right fell to the ground whilst the other two fell onto the roof. Detail from the etching Prospectus Septentrionalis by Francis Place after Robert Thacker. � The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Museum number: 1865,0610.948 (see below)

Although Flamsteed's correspondence rarely mentions domestic matters, the little we know about the damage that occured to the Observatory comes from a letter written by Flamsteed to his former assistant Abraham Sharp on 18 December:

'The publick papers have told you of a violent Hurricane that hapned here this day was 3 weeks in the Morneing. it threw open the Cover of the sextant else it had broke it. brok down all my chimnyes and carried and threw the bricks. of that on the east side of the roofe against the easterne out wall of the Yard. the Westerne chimnys falleing on the leades kept them from being torne off by the violent wind the south and North Windows in the great room were miserably torne. and the others escaped with some but not inconsiderable damage. the house at the further end of the yard is all untiled. so that 10li [£] will not repayre the damage here. I was told last night the Hurricane raged allso in France. Paris looks as if had sufferd a bombardment as also Roane what hurt their Navy has susteined wee heare not but beleive that tis not inconsiderable: so much for the Hurricane' (Correspondence)

It is unclear if the 'house at the end of the yard' was the Necessary House (i.e. the toilet, which stood in the south-western corner of the Observatory enclosure) or one of the two summer houses, one of which can be seen in the view above.

Damage in Greenwich Park

The full extent of the damage in Greenwich Park is not recorded though Daniel Defoe does tell us in his book The Storm (1704) that 'at Greenwich Park there are several pieces of the [Park] Wall down for an Hundred Rods [5.5 yards] in a Place' and that over 100 elm trees were blown down in St James's Park.

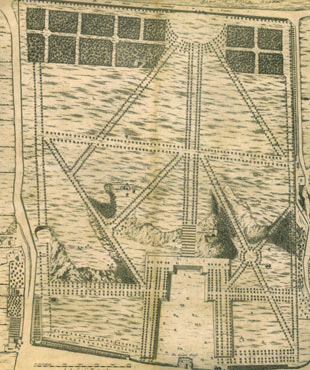

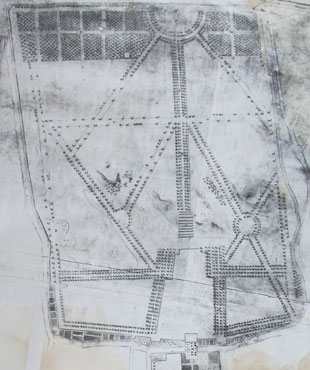

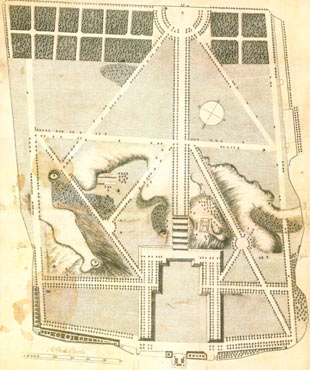

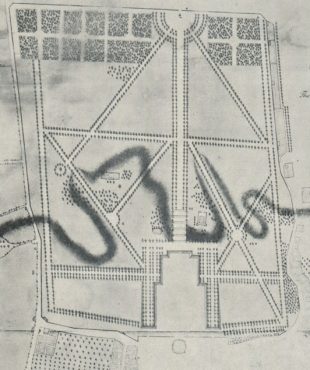

Although no direct record however has been found of damage to the trees at Greenwich, some information can possibly be gleaned from early plans of the Park, though great caution is required. The five earliest known plans that show the Park in any detail are the undated 'Pepys Plan' (c.1677), the 'Gascoin Plan' (1693), The Travers Plan (1695/7), the undated 'Woodlands Plan' (1700?–1720) and the undated 'Wise Plan' which appears to date from some time after about 1710. All apart from the Travers Plan (which draws heavily on the Gascoin Plan) purport to show the individual positions of many of the trees. Thumbnails of the Park as shown on the Pepys, Gascoin, Woodlands and Wise Plans are reproduced below with south at the top:

In their excellent and hugely useful Greenwich Park Historical Survey which was published in 1986, Land Use Consultants (LUC) speculated that the gaps shown in the avenues of trees in the Woodlands Plan may have been the result of the storm. Over the years, this has been restated by others as fact and become deeply embedded. What LUC actually said was (p.52):

'The 'Woodlands' plan, made sometime between 1703-20, confirms great losses of plateau trees [at the south end of the Park] compared to those shown in a 1695 plan [The Travers Plan]. This was probably due to the great storm of 1703, or may in part simply reflect the difficulties of establishing trees in the free draining plateau soils'

The speculation about the losses being due to the storm of 1703 is demonstrably incorrect. Although LUC were aware of the 1693 Gascoin plan on which the Travers Plan is partly based, they had clearly either never looked at it or had not looked at it properly because like the Woodlands Plan, the Gascoin Plan too shows great gaps in the avenues in much the same places. This suggest that the Woodlands Plan might well predate the storm. Where the Gascoin and Woodlands plans do differ on the tree front is in how they depict the trees at the viewpoint on the edge of the hill to the Observatory's east. The Pepys Plan shows four trees. The Gascoine Plan shows two and the Wise Plan shows none. The Woodlands Plan however shows a single tree with a large diameter circular fence around it, suggesting it had been relatively newly planted and that the fence was to protect it from grazing deer which at that time roamed across the whole of the Park. So was this tree planted before or after the storm? At present, we just do not know.

Both the Pepys Plan and the Wise Plan are schematic and show what appears to be idealised views. The Pepys plan is almost certainly based on earlier plans that were drawn when the Park was being landscaped in the early 1660s. Given the scale of the likely tree losses in the storm, what the four plans really tell us about the distribution of trees in the Park needs to be treated with a degree of scepticism.

Today, the hill with the viewpoint is know as One Tree Hill. However, the Gascoin and Travers Plans both label it as Five Tree Hill. Exactly when after the planting shown on the Woodlands Plan, the hill became known as One Tree Hill is unknown. By the 1750s, the name had become deeply embedded and appears on several prints that were published around that time.

Further reading and viewing

December 1703 Windstorm 300-year retrospective. Risk Management Solutions (2003)

Britain's Biblical Storm, The Great Storm of 1703, Chris Green (YouTube)

Acknowledgements

The view of Flamsteed House is reproduced under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license, courtesy of the The Trustees of the British Museum. Museum number: 1865,0610.948.

© 2014 – 2025 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan