…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

The original copy of the 1714 Longitude Act in the Parliamentary Arcives

Queen Anne (1655�1714). Oil on Canvas by Michael Dahl, c.1702. � National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence (see below)

The first part of this page examines the passage of the Bill through Parliament. The second is a study of the Original Act deposited in the Parliamentary Archives and the various printed copies of it. The final part looks at some of the shortcomings of the act as perceived by Newton and Flamsteed.

The following note about how parliamentary acts were drafted is taken from the website of the Parliamentary Archives.

‘Up to 1849, following its report stage (before third reading) in the first House, the text of a public bill was copied onto parchment. This document is known as an "engrossed bill”. Amendments made at third reading were also entered on the engrossed bill, but additional clauses were engrossed on separate pieces of parchment (known as “riders”) which were then stitched to the bill. All amendments in the second House were written on separate pieces of paper, and were not added to the bill until they had been agreed by both Houses. Engrossed Bills, from 1497 to 1849, became, after Royal Assent, the Original Acts themselves. Since 1849, public Original Acts have been printed following Royal Assent.’

The passage of the act through parliament

The parliamentary process commenced with either one, or possibly two petitions being read in the House of Commons and ended roughly two months later with Royal Assent being given in the House of Lords on 9 July. The passage of the Bill is recorded in the following volumes, from which the relevant entries have been transcribed below.

Volume 17 of The Journals of the House of Common Alternative Link

Volume 19 of The Journals of the House of Lords

Volume 5 of The History and Proceedings of the House of Commons

William Whiston. Oil on canvas after Sarah Hoadly, c.1720. � National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence (see below)

Sir Isaac Newton by Sir Godfrey Kneller, Bt. Oil on canvas, feigned oval, 1702. � National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence (see below)

‘We are ready to disclose it to the world, if we may be assured that no other persons shall be allowed to deprive us of those rewards which the public shall think fit to bestow for such a discovery; but do not desire actually to receive any benefit of that nature till sir Isaac Newton himself, with such other proper persons as shall be chosen to assist him, have given their opinion in favour of this discovery.’

Newton (who had been President of the Royal Society since 1703) arranged to meet Ditton on 23 March 1714 (Newton Correspondence, Volume 6, p77). Although there is no evidence as to what was discussed or who requested the meeting, it is summised that they discussed the proposal, which involved firing rockets at fixed times from vessels moored in known locations. Newton was subsequently called to give evidence to the Parliamentary Committee called to examine the merit of the petition(s).

Volume 5 of The History and Proceedings of the House of Commons, covers the years 1713–1714, but was not published until 1742, by which time, nearly 30 years had elapsed since the act was passed. It mentions only one petition, the text of which it gave in full, stating that it was presented by Whiston and Ditton towards the end of April 1714. In 1996, AJ Turner (The quest for longitude pp. 16 & 128) published the text of a printed copy of a petition preserved in the Houghton Library, Harvard University. It bore no names, but carried the date of 29 April 1714, the text being essentially identical to that published in The History and Proceedings.

Likewise, The Journals of the House of Commons only mention a single petition, but state it was presented on 25 May by ‘several Captains of her Majesty’s Ships, Merchants of London, and Commanders of Merchantmen, in behalf of themselves, and all others concerned in the Navigation of Great Britain’’.

The History and Proceedings of the House of Commons tells the story of what happened as follows:

Towards the latter End of April [1714], Mr. William Whiston, M. A. and Mr. Humphry Ditton, Master of the New Mathematical School in Christ's Hospital, London, having as they thought, found a new Method, for discovering the LONGITUDE both at Land and Sea, were encouraged by some Gentlemen to apply themselves to the House of Commons for a Reward, which they did in the following Paper, or Petition,

‘Whereas her Majesty has been pleased, this very Sessions of Parliament, particularly to recommend the Improvement Petition of Mr. of the Trade and naval Force of Great Britain, from the Throne: And whereas it is known, that nothing can be either at home or abroad, more for the common Benefit of Trade and Navigation, than the Discovery of the Longitude at Sea which has been so long desired in vain, and for want of which so many Ships and Men have been lost: Whereas also a Proposal for that Purpose has now been offered to the World for some Time, and has met with Approbation among some of the best Judges, to whom it has been privately discovered, but, for Want of any suitable Encouragement, could not hitherto be communicated to the Public: It is humbly desired, that a Bill, or Clause of a Bill, may be brought in this Parliament, to appoint a suitable Reward, for such as shall first lay before the Public, any sure Method for the Discovery of that Longitude; to be then due, when the most proper Judges, who may be appointed in the Bill, shall declare that such Method is both true in it self, and is also practicable at Sea; That the lowest Reward may be allotted to the discovering the same within one whole Degree of a great Circle, or seventy measured Miles; a greater to the discovering it within one half and a still greater to the discovering it within one Quarter of that Measure: And that withal, if it be thought fit, proper Rewards may be also allotted to such as shall afterward make any farther considerable Improvements for the perfecting so important a Discovery. This is the humble Desire of the Authors of this Invention, as well as of many others; who are unwilling that this their Native Country of Great Britain should lose the Honour and Advantage of its first Discovery, Practice and Encouragement.’

April 29, 1714.

The House appointed a Committee, to consider what Encouragement was fit to give to such as should find out the Longitude; which Committee, having on the 4th of June, asked Mr. Whiston and Mr. Ditton some Questions, in the Presence of Sir Isaac Newton, Dr. Halley, and some other celebrated Mathematicians, came to these two Resolutions,

1. ‘That it is the Opinion of this Committee, that a Reward be settled by Parliament, upon such Person or Persons, as shall discover a more certain and practicable Method of ascertaining the Longitude, than any yet in Practice, and that the said Reward be proportioned to the Degree of Exactness to which the said Method shall reach.’

2. That the House be moved, that Leave be given for a Bill to be brought in accordingly.

The 11th, the House took into their Consideration, the two Resolutions before mentioned, which were agreed to, and a Bill was ordered to be brought in, upon the first. [History, p.144]

The Journals of the House of Commons and House of Lords tell the story rather differently, but both sources mention that the Committee Report, was considered by the House on 11 June.

25 May, House of Commons

A Petition of several Captains of her Majesty’s Ships, Merchants of London, and Commanders of Merchantmen, in behalf of themselves, and all others concerned in the Navigation of Great Britain, was presented to the House, and read; setting forth, That the Discovery of the Longitude is of such Consequence to Great Britain, for Safety of the Navy, and Merchant Ships, as well as Improvement of Trade, that, for want thereof, many Ships have been retarded in their Voyages, and many lost; but if due Encouragement were proposed by the Publick, for such as shall discover the fame, some Persons would offer themselves to prove the fame, before the most proper Judges, in order to their entire Satisfaction, for the Safety of Mens Lives, her Majesty’s Navy, the Increase of Trade, and the Shipping of these Islands, and the lasting Honour of the British Nation: And praying their Petition may be taken into Consideration.

Ordered, That the said Petition be referred to the Consideration of a Committee: And that they do examine the Matter thereof; and report the fame, with their Opinion thereupon, to the House:

And it is referred to Mr. Clayton, Mr. Lowndes, Mr. Coventry, Mr. Oliphant, General Stanhope, Mr. Bulteel, Mr. Walpole, Mr. Attorney-General, Sir Wm. Whitlocke, Mr. Robarts, Mr. Lockwood, Mr. Moor, Mr. Hutchinson, Mr. Southwell, Mr. Gore, Mr. Gwyn, Mr. Lowther, Mr. Sheppard, Mr. Bathurst, Lord Lumley, Mr. Compton, Colonel Trevanion, Sir Jacob Banks, Mr. Collier, Mr. Craggs, Sir Edward Godyer, Sir Christo. Musgrave, [L]ord Finch, Sir Wm. St. Quintin, Mr. Cholmondley, Sir Richard Onslow, Captain, Chapman, Mr. Quick, Mr. Finch, Mr. Secretary BromIey, Mr. Fairfax, Mr. Middleton; Mr. Carew, Mr. Musgrave, Mr. Morice, Mr. Earl, Lord Haryley, Dr. Paske, Mr. Windsor, Mr Onslow, Mr. Chancellor of the Exchequer, Mr. Campion, Mr. Solicitor General, Mr. Freman, Mr. Aldworth, Mr. Vice Chamberlain; and all the Members that are employed in any Office in the Admiralty or Navy: And they are to meet this Afternoon, at Five a Clock, in the Speaker's Chamber: And have Power to send for Persons, Papers, and Records: And have Leave to fit in a Morning, if they think fit. [Link, p.641]

7 June, House of Commons

Mr Clayton reported from the Committee, to whom the Petition of Several Captains of her Majesty’s Ships, Merchants of London, and Commanders of Merchantmen, relating to the finding out of the Longitude at Sea, was referred, the Matter, as it appeared to them: and he read the same in his Place; and afterwards delivered the same in at the Clerk’s Table.

Ordered, That the said Report do lie upon the Table. [Link, p.671]

10 June, Whiston & Ditton’s flyer

Following the meeting of the Committee and its report being tabled, Whiston and Ditton released a flyer, the text of which was transcribed into an article about longitude in Abraham Rees’ The Cyclopædia, Or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, Volume 21, (1819):

Reasons for a Bill, proposing a Reward for the Discovery of the Longitude.

I. This bill is unexceptionable, because it is general, and not confined to any one project, person, or method; but gives equal hopes to all judicious proposers whatsoever.

II. Because in this bill no money is insisted on, before any method for the discovery of the longitude is, upon trial, actually found practicable and useful.

III. Because sir Isaac Newton’s own paper, delivered into the Committee, gives hopes that the known method by the theory of the moon, which is hitherto not exact enough, may, upon due encouragement, in time be brought to perfection.

IV. Because the method now proposed [i.e. their own method] is owned by all, to whom it has been communicated, to be certainly true in theory: it cannot, therefore, be fit to have it concealed, even though it were not yet known to be practicable; because, in that case, future improvements might still make it so.

V. Because its great use at land and in geography is indisputable, and was distinctly observed by sir Isaac Newton and Dr. Halley, upon the first proposal of this method to them: and we beg leave to say, that this use alone is so great and extensive, that if there were no other, it would highly deserve the encouragement of the public. .

VI. Because another great use is also undoubted, viz. for all places in the narrow seas, and within about 100 miles of all shores and islands; that is, for all places where ships are in the greatest danger, as sir Isaac Newton owned to the committee; so that if this method extended no farther, yet it would highly deserve the public encouragement.

VII, Because there is little or no reason to doubt of its use at any place at sea, even where ships are allowed to be in the least danger; since, in the most doubtful case of all, sir Isaac Newton has, in his paper delivered to the committee, proposed an effectual remedy, as will be clearly understood, when the method itself is known to the world.

VIII. Because this method will save the nation great sums of money, which the want of it does now occasion, as will appear upon trial.

IX. Because the charges of it will be inconsiderable, in comparison of the advantage, as will also fully appear upon trial.

X. Because it will prevent the loss of abundance of ships and lives of men; as it would certainly have saved all Sir Cloudesly Shovel’s fleet, had it then been put in practice.

XI. Because it is easy to be understood and practised by ordinary seamen, without the necessity of any puzzling calculations in astronomy.

And we take leave to recommend the learned Savilian professor of geometry at Oxford, Dr. Halley, as the fittest person in the world for the trial, and practice, and improvement of this method; and do hereby declare, that we are willing that he go equal shares with us in the reward, if he please to undertake so useful a work, and the public please to make that reward equivalent to the great dignity and importance of the discovery.

June 10, 1714.

WILL. WHISTON.

HUMPHREY DITTON.

11 June 1714, House of Commons

The House proceeded to take into Consideration the Report from the Committee, who were to consider of what Encouragement was fit to be given to such as should find out the Longitude at Sea:

And the same was read; and the Resolutions of the Committee thereupon: Which Report, and Resolutions, are as follow; viz.

That it appeared to the said Committee as followeth; viz.

Mr. Ditton and Mr. Wiston, being examined, did inform the Committee, That they had made a Discovery of the Longitude; and were very certain, that the same was true in the Theory; and did not doubt but that, upon due Trial made, it would prove certain and practicable at Sea:

That they had communicated the whole History of their Proceedings towards the said Discovery to Sir Isaac Newton, Dr. Clark, Mr. Haley, and Mr. Cotes; who all seemed to allow of the Truth of the Proposition, as to the Theory: but doubted of several Difficulties that would arise in the Practice.

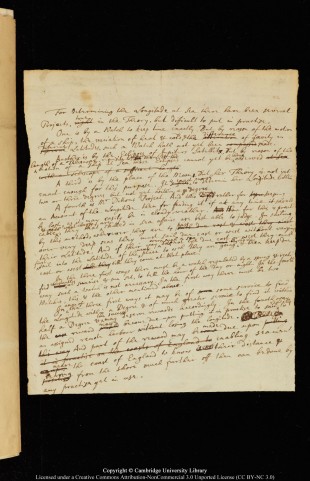

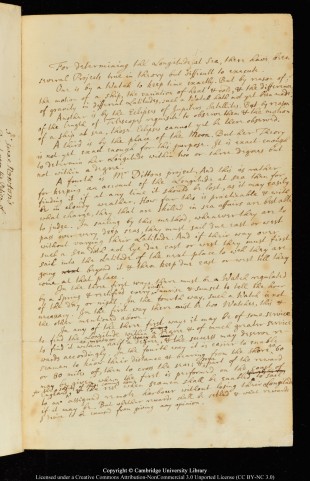

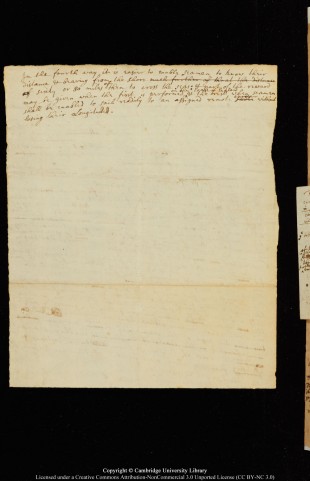

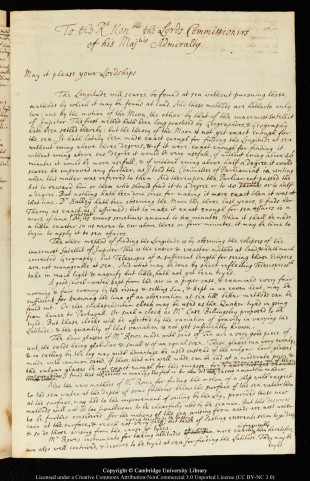

Newton's copy of the evidence he submitted in writing to the Committee. Apart from the punctuation and the insertion of the words 'Wet and Dry' in the second paragraph, the substitution of Great Britain for England in the last paragraph, and the omission of his last sentence: 'But whether rewards shall be setled [?] & what rewards I desire to be excused from giving any opinion.', it is identical to the text reproduced in the The Journals of the House of Commons. A digital copy of an earlier draft can be see below. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

Sir Isaac Newton, attending the Committee, said, That, for determining the Longitude at Sea, there have been several Projects, true in the Theory, but difficult to execute:

One is, by a Watch to keep Time exactly: But, by reason of the Motion of a Ship, the Variation of Heat and Cold, Wet and Dry, and the Difference of Gravity in different Latitudes, such a Watch hath not yet been made:

Another is, by the Eclipses of Jupiter’s Satellites: But, by reason of the Length of Telescopes requisite to observe them, and the Motion of a Ship at Sea, those Eclipses cannot yet be there observed:

A Third is, by the Place of the Moon: But her Theory is not yet exact enough for this Purpose: It is exact enough to determine her Longitude within Two or Three Degrees, but not within a Degree:

A Fourth is, Mr. Ditton’s Project: And this is rather for keeping an Account of the Longitude at sea, than for finding it, if at any time it should be lost, as it may easily be in cloudy Weather: How far this is practicable, and with what Charge, they that are skilled in Sea-affairs are best able to judge: In sailing by this Method, whenever they are to pass over very deep. Seas, they must sail due East, or West, without varying their Latitude; and if their Way over such a Sea doth not lie due East, or West, they must first sail into the Latitude of the next Place to which they are going beyond it; and then keep due East, or West, till they come at that Place:

In the Three first Ways there must be a Watch regulated by a Spring, and rectified every visible Sun-rise and Sun-set, to tell the Hour of the Day, or Night: In the Fourth Way, such a Watch is not necessary: In the First Way, there must be Two Watches; this, and the other mentioned above:

In any of the Three first Ways, it may be of some Service to find the Longitude within a Degree; and of much more Service to find it within Forty Minutes, or Half a Degree, if it may be; and the Success may deserve Rewards accordingly:

In the Fourth Way, it is easier to enable Seamen to know their Distance, and Bearing from the Shore, 40, 60, or 80, Miles off, than to cross the Seas; and some Part of the Reward may be given when the First is performed on the Coast of Great Britain, for the safety of Ships coming Home; and the rest, when Seamen shall be enabled to sail to an assigned remote Harbour without losing their Longitude, if it may be.

Dr. Clarke said, That there could no Discredit arise to the Government, in promising a Reward in general, without respect to any particular Project, to such Person or Persons who should discover the Longitude at Sea,

Mr Halley said, That Mr. Ditton’s Method for finding the Longitude did seem to him to consist of many Particulars, which first ought to be experimented, before he could give his Opinion; and that it would cost a considerable Sum to make the Experiments, but what the Expence would amount to, he could not tell.

Mr. Whiston affirmed, That the undoubted Benefit which would arise on the Land, and near the Shore, would vastly surmount the Charges of Experiments.

Mr. Cotes said, That the Project was right in the Theory near the Shore; and the practical Part ought to be experimented.

And, upon the whole Matter, the Committee came to these Resolutions; viz.

Resolved, That it is the Opinion of this Committee, That a Reward be settled by Parliament upon such Person or Persons as shall discover a more certain and practicable Method of ascertaining the Longitude, than any yet in Practice; and the said Reward be proportioned to the Degree of Exactness to which the said Method shall reach.

Resolved, That it is the Opinion of this Committee, That the House be moved, That Leave be given for a Bill to be brought in accordingly.

The First Resolution being read a Second time; Resolved, Nemine contradicente, That the House doth agree with the Committee in the said Resolution, That a Reward be settled by Parliament upon such Person or Persons as shall discover a more certain and practicable Method of ascertaining the Longitude, than any yet in Practice; and the said Reward be proportioned to the Degree of Exactness to which the said Method shall reach.

Ordered, That Leave be given to bring in a Bill, upon the said Resolution: And that Mr. Clayton, Mr. Aislaby, Sir George Beaumont, Sir Wm. Whitlocke, Mr. Boscawen, Sir Thomas Hardy, Mr. Addison, General Stanhope, and Sir John Leake, do prepare, and bring in, the same. [Link, pp.677–678]

Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

16 June, House of Commons

General Stanhope presented to the House, according to Order, a Bill for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude: And the same was received. [Link, p.686]

17 June, House of Commons

A Bill for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude, was read for the First Time.

Resolved, That the Bill be read a Second time. [Link, p.687]

22 June, House of Commons

A Bill for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude, was read a Second time.

Resolved, That the Bill be committed.

Resolved, That the Bill be committed to a Committee of the whole House.

Resolved, That this House will, upon Thursday Morning next, resolve itself into a Committee of the whole House, upon the said Bill. [Link, p.692]

24 June, House of Commons

Resolved, That this House will, upon Tuesday Morning next, resolve itself into a Committee of the whole House, upon the Bill for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude. [Link, p.700]

29 June, House of Commons

‘The Order being read, for the House to resolve itself into a Committee of the whole House, upon the Bill for providing a publick Reward for such Persons or Persons as shall discover the Longitude:

Resolved, That this House, will, To-morrow Morning at Eleven a Clock, resolve itself into a Committee, upon the said Bill.’ [link, p.708]

30 June, House of Commons

The House, according to Order, resolved itself into a Committee of the whole House, upon the Bill for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude.

Mr. Speaker left the Chair.

General Stanhope took the Chair of the Committee.

Mr. Speaker resumed the Chair.

General Stanhope reported from the Committee, That they had gone through the Bill, and made several Amendments thereunto; which they had directed him to report, when the House will please to receive the same.

Ordered, That the Report be received To-morrow Morning. [Link, p.711]

1 July, House of Commons

General Stanhope, according to Order, reported from the Committee of the whole House, to whom the Bill for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude was committed, the Amendments they had made to the Bill; and directed him to report to the House; and he read the same in his Place; and afterwards delivered the Bill, and Amendments, in at the Clerk’s Table: Where the Amendments were once read throughout; and then a Second time, one by one; and, upon the Question severally put thereupon, with an Amendment to One of them, agreed unto by the House.

Ordered, That the Bill, with the Amendments, be ingrossed. [Link, p.712]

3 July, House of Commons

‘An engrossed Bill, intituled, An Act for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude at Sea, was read for the Third time,

An Amendment was proposed to be made to the Bill; Pr * L. * After “time” to insert “the Right honourable Thomas Earl of Pembroke and Mountgomery, Philip Lord Bishop of Hereford, George Lord Bishop of Bristol, Thomas Lord Trevor:” And the same was, upon the Question put thereupon, agreed unto by the House: And the Bill was amended at the Table accordingly.

Resolved, That the Bill do pass: And that the Title be, An Act fro providing a publick Reward for such Persons as shall discover the Longitude at Sea.

Ordered, that General Stanhope do carry the Bill to the Lords and desire their Concurrence. [Link, pp.715–716]

3 July, House of Lords

A Message was bought from the House of Commons, by General Stanhope and others:

With a Bill intituled “An Act for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude at Sea;” to which they desire the Concurrence of this House. [link.p.742]

5 July, House of Lords

Hodie 1a vice lecta est Billa, intituled, intituled “An Act for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude at Sea;” [link.p.745]

7 July, House of Lords

Hodie 2a vice lecta est Billa, intituled, intituled “An Act for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude at Sea;”

ORDERED, that the said Bill be committed to a Committee of the whole House, presently.

Then the House was adjourned during Pleasure and put into a Committee thereupon.

And, after some Time spent therin, the House was resumed.

And the Lord Bishop of Ely reported from the said Committee, “That they had gone through the Bill: and directed him to report the same to the House, without any Amendment.”

Then the Bill was read the Third Time.

And the Question being put, “Whether this Bill shall pass?”

It was Resolved in the Affirmative. [link.p.750]

8 July, House of Commons

A MESSAGE from the Lords, by Sir Tho. Gery, and Mr. Rogers:

Mr Speaker, The Lords have agreed to a Bill intituled, …

Also

To a Bill intituled, An Act for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude at Sea, without Amendment: [Link, p.721]

9 July, House of Commons

A Message from her Majesty, by Sir William Oldes, Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod:

Mr. Speaker,

The Queen commands this honourable House to attend her Majesty, in the House of Peers, immediately.

Accordingly, Mr. Speaker, with the House, went up to attend her Majesty, in the House of Peers: Where her Majesty was pleased to give the Royal Assent to several publick and private Bills: [Link, p.724]

9 July, House of Lords

Her Majesty, being seated on Her Royal Throne, adorned with Her Crown and Regal Ornaments, and attended with Her Officers of State (the Lords being in their Robes); commanded the Gentleman Usher of Black Rod to let the House of commons know, ‘That it is Her Majesty’s Pleasure they attend Her immediately, in the House of Peers.’

Who being come, with their Speaker; he, after a Speech made to Her Majesty, delivered the Money Bill to the Clerk Assistant (in the Absence of the Clerk of the Parliament), who bought it to the Table; where the Clerk of the Crown read the Titles of the Bills to be passed, severally, as follows:

1. ‘An Act …

… ...

6. ‘An Act for providing a Public Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude at Sea.’

… ...

To these Bills the Royal Assent was severally pronounced, in these Words: (videlicet,)

‘La Reine le veult.’ [Link, pp.758–9]

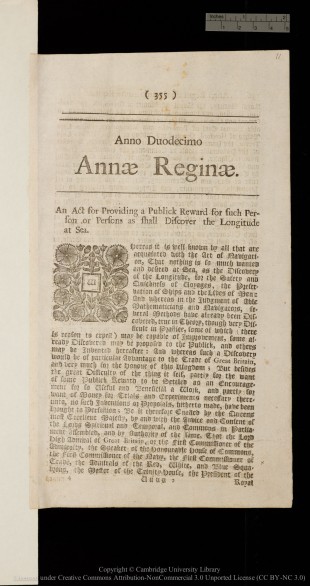

The Parliamentary Act

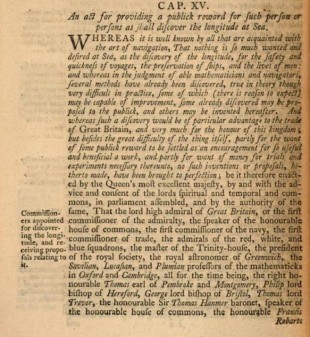

The first page of the first printed edition of the 1714 act. Printed by John Baskett, Printer to the Queens most Excellent Majesty, 1714. Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

The opening of the act as published by Pickering in The statutes at large, Volume 13 (1764). Digitised by Google from the Library of Stanford University

As was the norm, the original act has no punctuation or paragraphs and is written as a solid block of text with any gaps at the end of a line struck out to prevent additional words being added at a later date.

Unlike the original act, the first printed copies were punctuated and subdivided into clauses. Spellings were also altered. Royall for example was printed as Royal.

In later printings, part of the text was italicised, the clauses numbered and notes added in the margin. The text of the act reproduced below, has been taken (with the italics removed) from Pickering’s The Statutes at Large, Vol 13, p.116 (1764). Additions and alterations to the text made on the parchment have been underlined. Whilst some appear to have been drafting errors that have been corrected, the addition of the four named commissioners from the House of Lords was an amendment made and added to the text at the time of the third reading.

WHEREAS it is well known by all that are acquainted with the art of navigation, That nothing is so much wanted and desired at Sea, as the discovery of the longitude, for the safety and quickness of voyages, the preservation of ships, and the lives of men: and whereas in the judgment of able mathematicians and navigators, several methods have already been discovered, true in theory though very difficult in practice, some of which (there is reason to expect) may be capable of improvement, some already discovered may be proposed to the publick, and others may be invented hereafter. And whereas such a discovery would be of particular advantage to the trade of Great Britain, and very much for the honour of this kingdom; but besides the great difficulty of the thing itself, partly for the want of some publick reward to be settled as an encouragement for so useful and beneficial a work, and partly for want of money for trials and experiments necessary thereunto, no such inventions or proposals, hitherto made, have been brought to perfection; be it therefore enacted by the Queen’s most excellent majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the lords spiritual and temporal and commons, in parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, That the lord high admiral of Great Britain, or the first commissioner of the admiralty, the speaker of the honourable house of commons, the first commissioner of the navy, the first commissioner of trade, the admirals of the red, white, and blue squadrons, the master of the Trinity-house, the president of the royal society, the royal astronomer of Greenwich, the Savilian, Lucasian, and Plumian professors of the mathematicks in Oxford and Cambridge, all for the time being, the right honourable Thomas earl of Pembroke and Montgomery, Philip lord bishop of Hereford, George lord bishop of Bristol, Thomas lord Trevor, the honourable Sir Thomas Hanmer baronet, speaker of the honourable house of commons, the honourable Francis Robarts esq; James Stanhope esq; William Clayton esq; and William Lowndes esq; be constituted, and they are hereby constituted commissioners for the discovery of the longitude at sea, and for examining, trying, and judging of all proposals, experiments, and improvements relating to the same; and that the said commissioners, or any five or more of them, have full power to hear and receive any proposal or proposals that shall be made to them for discovering the laid longitude; and in case the said commissioners, or any five or more of them, shall be so far satisfied of the probability of any such discovery, as to think it proper to make experiment thereof, they shall certify the same under their hands and seals, to the commissioners of the navy for the time being, together with the persons names, who are the authors of such proposals; and upon producing such certificate, the said commissioners are hereby authorized and required to make out a bill or bills for any such sum or sums of money, not exceeding two thousand pounds, as the said commissioners for the discovery of the said longitude, or any five or more of them, shall think necessary for making the experiments, payable by the treasurer of the navy; which sum or sums the treasurer of the navy is hereby required to pay immediately to such person or persons as shall be appointed by the commissioners for the discovery of the said longitude, to make those experiments, out of any money that shall be in his hands, unapplied for the use of the navy.

II. And be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid, That after experiments made of any proposal or proposals for the discovery of the said longitude, the commissioners appointed by this act, or the major part of them, shall declare and determine how far the same is found practicable, and to what degree of exactness.

III. And for a due and sufficient encouragement to any such person or persons as shall discover a proper method for finding the said longitude, be it enacted by the authority aforesaid, That the first author or authors, discoverer or discoverers of any such method, his or their executors, administrators, or assigns, shall be entitled to, and have such reward as herein after is mentioned; that is to say, to a reward, or sum of ten thousand pounds, if it determines the said longitude to one degree of a great circle, or sixty geographical miles; to fifteen thousand pounds, if it determines the same to two thirds of that distance; and to twenty thousand pounds, if it determines the fame to one half of the same distance; and that one moiety or half-part of such reward or sum shall be due and paid when the said commissioners, or the major part of them, do agree that any such method extends to the security of ships within eighty geographical miles of the shores, which are places of the greatest danger, and the other moiety or half-part, when a ship by the appointment of the said commissioners, or the major part of them, shall thereby actually fail over the ocean, from Great Britain to any such port in the West-Indies, as those commissioners, or the major part of them, shall choose or nominate for the experiment, without losing their longitude beyond the limits before mentioned.

IV. And be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid, That as soon as such method for the discovery of the said longitude shall have been tried and found practicable and useful at sea, within any of the degrees aforesaid, That the said commissioners, or the major part of them, shall certify the same accordingly, under their hands and seals, to the commissioners of the navy for the time being, together with the person or persons names, who are the authors of such proposal; and upon such certificate the said commissioners are hereby authorized and required to make out a bill or bills for the respective sum or sums of money, to which the author or authors of such proposal, their executors, administrators, or assigns, shall be entitled by virtue of this act; which sum or sums the treasurer of the navy is hereby required to pay to the said author or authors, their executors, administrators, or assigns, out of any money that shall be in his hands unapplied to the use of the navy, according to the true intent and meaning of this act.

V. And it is hereby further enacted by the authority aforesaid, That if any such proposal shall not, on trial, be found of so great use, as aforementioned, yet if the same, on trial, in the judgment of the said commissioners, or the major part of them, be found of considerable use to the publick, that then in such case, the said author or authors, their executors, administrators, or assigns, shall have and receive such less reward therefore, as the said commissioners, or the major part of them, shall think reasonable, to be paid by the treasurer of the navy, on such

certificate, as aforesaid.

Digitised copy of the original 1714 Longitude Act

Catalogue Record at the Parliamentary Archives

The acts shortcomings

One of the first proposals to be submitted was that of Whiston and Ditton, who submitted their offering in the form of a small book titled: A new method for discovering the longitude both at sea and land, humbly proposed to the consideration of the publick, (1714). The introduction is dated 7 July 1714 (p.27) – the same date that the Bill completed its passage through Parliament. Click here to view a transcribed version. Click here to view the second edition published in 1715.

A major shortcoming of the act was that it gave no guidance as to how it was to work in practice. It did not establish a Board structure, nor did it provide for any staff such as a secretary. Nor did it state how individuals were to submit their proposals, who it was who was supposed to summon the commissioners to a meeting or who was supposed to chair it, or where the commissioners were supposed to meet. Partially resolved by the appointment of a secretary in 1763, the lack of formalised structures was to be problematic for over 100 years until the passing of the 1818 Longitude Act.

As Astronomer Royal and President of the Royal Society respectively, both Flamsteed and Newton became commissioners on the passing of the act. Both had something to say on the matter.

Writing to his former assistant Abraham Sharp on 31 August 1714, Flamsteed wrote (transcribed from Cudworth's The life and correspondence of Abraham Sharp, (1889) where the spellings have been modernised and the letter slighly abridged. For the missing paragraph see Baily’s Flamsteed (1835). For a full transcript with original spellings see Volume 3 of Flamsteed’s Correspondence, pp.700–703. For the original see RS MS.798.89):

THE OBSERVATORY, August 31st, 1714.

SIR,

About the middle of this month a couple of young Nonconformist preachers from Worksop in Derbyshire came hither to have my approbation of some method they had to propose for finding the longitude at sea, and I shall tell you because it will make you laugh abundantly. They proposed to have two or more strong vessels made of earth or glass, with a vent and stop-cock. The vent was to be filled up with an agate, or some very hard stone or metal that might admit a very small hole to be drilled in it, and then, this hole being closed, all the air was to be pumped out of the vessel by the help of an air pump, and then afterwards they were to open the small hole in the agate, and by a good pendulum clock to see in how long time the vessels should be filled again with air, for this being known they calculated that as fast as the vessel was discharged it would fill again in the same time precisely, and they had a contrivance as proper as this to know when the vessel was full. They also proposed to find it by the times of the high waters in the open sea, which they would find by a barometer and a timekeeper with a thermometer annexed to it, with a table for correcting of the clock. I received them very civilly, but refused to give them my hand to testify that I had seen their proposals, and advised them not to print them. They told my servant Joseph that they had come 150 miles purposely for this business, but I believe they took my advice, for I heard no more of them.

On July the 9th past Mr. Hobbs, a watchmaker, gave me a printed book whence he proposed the finding the longitude by a pendulum clock hanging by a contrivance so as to answer all the motions of a ship, so as he thought that would not affect the pendulum, and last Thursday, one Mr. Billingsley presented me with a printed proposal’ wherein he offers, over and above what Mr. Hobbs had done, to make a platform that a person might stand steadily upon to manage a large telescope to observe the eclipse of the heavenly bodies on board a ship. He seemed a man of better sense than Mr. Hobbs, and therefore when I had shown him that, whatever he imagined to the contrary, the pendulum would be shaken by every shock and motion of the ship and vibrations made wider or narrower than they ought to be, and this in the company of some very intelligent persons assented to what I urged, he held his peace, which is as much as I can expect from persons that have swelled themselves with the hopes of getting £20,000.

Yesterday Mr. Conyers Purcell left a letter for me with my servant Joseph, and in it another printed proposal to find the longitude by a waterwheel that should follow the ship and measure its way, which it will do like the way-wiser, over every wave and swell as well as when it is smooth. I have not seen this ingenious gentleman, but, allowing his contrivance to be liable to no other inconvenience but this, it is enough to render it ridiculous.

Mr. Whiston and Mr. Ditton’s proposals tend only to finding the distance of a ship at sea from any mark or coast from whence they can see a fire or hear a gun shot at twelve o’clock at night. You know that by experiments made here, November 10th and 15th in the year 1687, it was found that sound came from Shooter’s Hill hither in 13½ seconds. The Hill is three miles off, therefore the sound moved one mile in 4¼ seconds, so their proposal sinks from finding of the longitude to finding of the distance of the ship from a sea mark. I am sorry for them, and shall tell you no more of them but order their book to be sent this week to London, to be sent to you by Mr. Hodgson, who shall have a special charge about it.

‘Twas their attempt that occasioned the Act of Parliament that proposed a reward for any one who shall discover the longitude. In it I am named one of the commissioners, and this causes the pretenders to make their applications to me so much. If you desire it I shall send you a copy of the Act.

We reckon that the King [George 1.] is by this day in Holland, or will be to-morrow. He is to come ashore at Greenwich, to reside two nights in the Queen’s House, which is fitted up for him, and make his entry into London in his coaches. God send an happy arrival and reign, for the accession to the Crown has dissipated much of our fears and he is impatiently expected. Your affectionate friend and servant,

JOHN FLAMSTEED

Newton seems to have received submissions that were either sent to him directly, addressed to the President and fellows of the Royal Society or sent on to him from the Admiralty. Amongst his papers in the archives at Cambridge are drafts of a number of letters that show his frustration with the whole process and the amount of his time wasted in having to respond to hopeless schemes. The following two sentences appear at different points on a sheet with multiple crossings out that appears to be a draft of a letter sent in reply to a letter dated 11 October 1721 from Josiah Burchett (Secretary of the Admiralty), forwarding him a proposal for finding Longitude from a Mr Laurans (Newton Correspondence Vol 7, p.171).

‘The Commissioners appointed by ye Act of Parl. should have met in the beginning to agree about the meaning of the Act & the best method of putting it in execution, & to appoint a Committee to see things do if it should be thought fit. Since that has not been done,’

‘The Commissioners appointed by Act of Parliament should have met in the beginning to consider of the best method of putting the Act in execution, But [illegible] it is now too late,’ (MS Add.3972/37)

On a second sheet, containing a different draft of the same letter, Newton wrote:

‘And the first step for putting the Act in execution should have been to consider how Astronomy might by sufficiently [illegible] improved [large crossed out section] before it be applied to sea affairs.’ (MS Add.3972/40)

The actual letter that was sent seems not to have survived, making it impossible to know what sections of the two drafts were included or omitted.

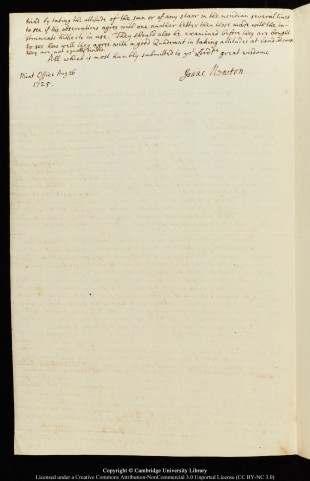

The draft of a later letter sent to the Admiralty is reproduced below. Dated 26 August 1725, the letter was sent in reply to one dated 12 August that he had received from Burchett asking him to examine a revised proposal submitted by Jacob Rowe and for his ‘Opinion of the same’ (Newton Correspondence Vol 7, p.328). As well as giving his view on Rowe’s submission, Newton went out of his way to spell out the kind of proposals that would be worthy of his review, the subtext being that the Admiralty should stop forwarding him suggestions that were futile. The letter as sent was almost identical to the draft and is preserved at Christ Church College Oxford (MS350/4)

Draft of the letter sent by Newton to the Admiralty on 26 August 1725. It was received and read the same day it was sent.

Reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library (see below)

Acknowledgements

The following images are © National Portrait Gallery, London. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) licence.

Queen Anne. Oil on Canvas by Michael Dahl, c.1702. National Portrait Gallery Object ID: NPG 6187.

William Whiston. Oil on canvas after Sarah Hoadly, c.1720. National Portrait Gallery Object ID: NPG 243.

Sir Isaac Newton. Oil on canvas, feigned oval by Sir Godfrey Kneller, Bt., 1702. National Portrait Gallery Object ID: NPG 2881

The five images of Newton’s manuscripts are from Newton’s Papers (MS Add.3972/32&34) and are reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library.

Newton’s evidence to the Parliamentary Committee – Image 1, Image 2, Image 3

Newton’s letter to the Admiralty, 26 August 1725 – Image 1, Image 2

The image of the first page of the first printed edition of the 1714 act (RGO14/1/11) is reproduced under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0) courtesy of Cambridge Digital Library. The right hand margin has been trimmed, and the image is more compressed than the original.

© 2014 – 2025 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan