…where east meets west

- Home

- Brief History

- The Greenwich Meridian

- Greenwich

(1675–1958) - Herstmonceux

(1948–1990) - Cambridge

(1990–1998) - Outstations (1822–1971)…

- – Chingford (1822–1924)

- – Deal

(1864–1927) - – Abinger

(1923–1957) - – Bristol & Bradford on Avon

(1939–1948) - – Bath

(1939–1949) - – Hartland

(1955–1967) - – Cape of Good Hope

(1959–1971)

- Administration…

- – Funding

- – Governance

- – Inventories

- – Pay

- – Regulations

- – Royal Warrants

- Contemporary Accounts

- People

- Publications

- Science

- Technology

- Telescopes

- Chronometers

- Clocks & Time

- Board of Longitude

- Libraries & Archives

- Visit

- Search

Contemporary account from 1866

| Date: | 1866 |

| Author: | William Ellis, Assistant at the Royal Observatory |

| Title: | Lecture on the treatment of chronometers at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich |

| About: | This authoritative account comes from William Ellis who at that time was entrusted with the management of the galvanic apparatus for chronographic registry of Transits, movement of sympathetic clocks, and external distribution of time-signals; the receiving, issuing, and rating of chronometers; the raising or the Time-Signal-Ball at 1 o’clock; and the computations belonging to the same. The text of this lecture which was delivered on 1 March 1866 was published in the 1 April edition of The Horological Journal, (London) Vol. VII, (London) pp.85–92. |

| Images: | None |

| Click here to read the account as originally published |

[Note: For the purpose of clarity, this transcription contains a small number of minor changes to the original punctuaton.]

LECTURE ON THE TREATMENT OF CHRONOMETERS, AT THE ROYAL OBSERVATORY, GREENWICH.

Delivered March 1, 1866, before the Members of the British Horological Institute, at their Rooms, in Northampton Square.

By William Ellis, Esq., F.R.A.S., of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich.

John Jones, Esq., F.E.G.S., in the Chair.

On a previous occasion when I had the pleasure of addressing the Members of the British Horological Institute, I felt that I had a subject with which to deal, possessed of some attraction; but on the present occasion, speaking of chronometers to chronometer-makers, I am sensible that there is no similar novelty. Having however been given to understand that an account of the manner in which chronometers are tested at the Royal Observatory would be valued by the Members of the Institute, I willingly accede to the request which has been made to me, to place such an account before them.

In speaking of the treatment of chronometers at Greenwich, I propose, first, to confine myself to an account of the course pursued with the chronometers yearly sent by makers to the Royal Observatory for competitive trial. These trials were instituted in the first instance above 40 years ago, before which time there was no criterion by which to judge of the merits or value of a chronometer. The first trial was commenced in the year 1822. And for the purpose of stimulating improvement in the construction of chronometers, the Government offered for the best chronometer, the sum of £300, and for the next best, £200. Similar awards were made for several years; afterwards the sum of £500 was divided into three instead of two portions, £200, £170, £130, and awarded to the first three chronometers on the lists. In| a few years a point of excellence was reached, beyond which there did not seem prospect of further improvement for a considerable time, and in the year 1836, after thirteen trials, they were discontinued. They were afterwards again commenced, but on a different footing; the Government instead of giving prizes for the best chronometers, purchased them at a more reasonable price, and this practice is still followed. I will now proceed to describe the trial as it is at present conducted. And first, it is necessary to mention, that any maker who may desire to place a chronometer on trial at Greenwich should make application by letter to the Hydrographer,* at the Admiralty, some little time before the conclusion of the preceding year. The application should of course contain the name and address of the chronometer maker, and the number, if possible, of the chronometer proposed to be deposited. Each maker is in ordinary cases allowed to deposit one chronometer only, though in later years, greater indulgence in this respect appears to have been shown to makers of established reputation. The necessary permission to deposit the chronometer or chronometers at the Observatory will in due course be furnished to the maker, who will at the same time be informed of the day of deposit. This is always early in the month of January, and the chronometers must be brought on the day mentioned, otherwise they cannot be received. If we receive a great many chronometers, it is our practice at once to remove the covers from the boxes, in order that the chronometers may be placed more closely together, for economy of space, especially necessary when they come to be placed in the heating apparatus; but the chronometers are not removed from the gimbals. Proper precaution is used to keep off dust so long as the covers are removed from the boxes. No use is made of the rates preceding the first Saturday of trial; that is to say, the chronometers being received on a certain Monday, the trial really commences from the Saturday immediately following.

The first trial to which the chronometers are exposed is a trial in cold. As however, no attempt is made to produce artificial cold, the severity of such trial, in each particular year, depends on the comparative rigour of the season. Outside one of the northern windows of the chronometer room, there is constructed a kind of pent house, the interior of which, though protected from snow or rain, is exposed to the influence of the external atmosphere. It is in this house that the chronometers are placed during the coldest period of the winter season. Sometimes there are too many chronometers to permit of this being done; on such occasions they are allowed to remain in the chronometer room; those windows of the room having a northern aspect being then left open. After the trial in cold, the chronometers are usually kept a short time in the ordinary temperature of the room; they are then tried in heat. For this purpose they are placed in the chamber of a stove heated by gas, the heat at the commencement of the trial being increased gradually, and lowered gradually again towards its termination. The stove consists of a large open topped sheet iron casing, placed within another, larger, leaving a space between the two on all four sides and underneath. It is closed in above by lids opening upwards. The outer casing is double bottomed; its upper side is pierced with small holes, and between the upper and under side is a row of small gas jets (eight in all) by means of which the inner chamber is kept constantly surrounded (excepting above) by a jacket of warm air. Proper means are provided for carrying away the products of combustion, which cannot enter the chamber in which the chronometers are placed. The whole is inclosed in a wood casing, which further assists the maintenance of uniform temperature. The chronometers are supported in the inner chamber on light wood laths, and do not any of them touch the iron itself. In this first trial in heat, the temperature is usually not raised to a high point. The chronometers remain in heat for three or four weeks, and are then again removed into the room. Whilst now remaining in the room, they are rated in different positions as referred to the meridian, in order to discover whether they are, any of them, under the influence of magnetism. They remain one day with the XII placed north, one day with the XII east, one day with the XII south, and so on, continuing this kind of trial for several weeks, shifting every day each chronometer one quarter round. The daily rates are afterwards examined, to discover whether any trace of magnetic effect exists; but I am not aware that any certain or sensible effect, has ever been detected in any chronometer yet sent for trial. I may mention here, that a very marked effect was some years ago, found to exist in a chronometer belonging to the Government; to this I will refer presently. Before the termination of the trial, the chronometers are placed a second time in the stove; in this trial the heat is usually raised to a higher point than before, the maximum being now usually between 95° and 100°. They remain in heat for three or four weeks. After being removed from heat, they are rated in the room until the end of the month of July, about which time the trial usually terminates.

The complete course of trial having been gone through, the Astronomer Royal transmits to the Admiralty his usual annual report. It rests then with the Admiralty to offer to purchase from the makers, as many of the chronometers at the head of the list as seems desirable. But the continual additions thus made by annual purchase, and in other ways, to the Government stock (already very large) renders it necessary to limit considerably the number of chronometers taken, and each year many excellent instruments are returned to the makers. For the first few chronometers on the list, a rather higher price than the ordinary market price is offered. Some makers have said, that the prices offered for such chronometers do not repay them for their trouble. It should however be remembered that the continuation of the Greenwich trials is advantageous as much to chronometer-makers as the Government, who have no particular occasion at present to add greatly to their already large stock; and though they undoubtedly obtain in this way superior chronometers, the makers, on the other hand, whose names stand high on the list, naturally obtain some reputation from that circumstance, though probably it will be by young or new makers that such success will be the more highly valued.

As soon as the various makers, to whom offers to purchase have been made, have signified their assent, or the opposite, to the terms proposed, all chronometers that are purchased are returned to the makers to be cleaned before being used on government service, it being understood that the purchase money covers the expence of such cleaning. And at the same time the makers of all chronometers not purchased are requested to remove their chronometers from the Observatory. The rates of all the chronometers that have been on trial are then printed, and copies of the printed rates distributed to all makers who have had chronometers on trial, as well as to any others who may be desirous of possessing them. In the printed tables the chronometers are placed in a certain order of merit; the weekly rates only are given, as it is by these alone that the order of merit is determined. Three tables are given. The first contains, for each chronometer, the weekly rates arranged in the order of time. The second gives the same rates, but with the weeks arranged in the order of temperature of the different weeks, as determined by an instrument which we call a “chronometrical thermometer,” and which I will presently explain. The week of greatest cold is placed first, the next warmer week follows, and so on, the last week being that of greatest heat. By the first table we discover whether there exists acceleration of rate to any great extent, or any general irregularity such as might be caused by some imperfection in the machine or by bad oil. The second table gives more especially information as to the efficiency of the compensation, though this may be sometimes masked when large faults of the first-mentioned kinds exist. A third table gives, for each chronometer, the least weekly rate during the time of trial, and the greatest weekly rate, the difference of these numbers gives the greatest variation of weekly rate during the trial; this is found in the printed table in the column headed “Difference between the greatest and least.” In another column is given the greatest difference between any two successive weekly rates, or as it is called in the table the “Greatest Difference between one week and the next.” Of these two numbers, the “Difference between the Greatest and Least,” and the “Greatest Difference between one week and the next,” the latter indicates a sudden change of rate, the former may also result from a sudden change of rate, but is usually a measure of some gradual change of rate. Of the two evils, that indicated by the latter of the two numbers is evidently the worst, and greater importance is therefore attached to that number being small. And the practical rule which the Astronomer Royal has adopted for determining the order of merit of the chronometers (that is the order in which they appear in the printed tables) is, that it shall correspond to the order of magnitude of certain numbers, called “trial numbers,” that for each chronometer being found as follows;—

Trial No. = Difference between the Greatest and Least weekly rates, + 2 X Greatest Difference between one week and the next.

In this formula it will be remarked that the change which is the more obnoxious of the two has double weight given to it, so that a chronometer which shows a large change of this kind will have its trial number greatly increased, and its position in the table will in consequence be correspondingly low. This formula is considered, on the whole, to afford, in a simple way, a fair estimation of the relative merits of the different chronometers at the time of trial. Should a chronometer, from whatever cause, not undergo the complete trial, it is not placed with the other chronometers in order of merit, but is put into a separate division at the foot of the printed tables. I may remark that, in all the tables, the sign + indicates, as usual, a gaining rate, and the sign - a losing rate.

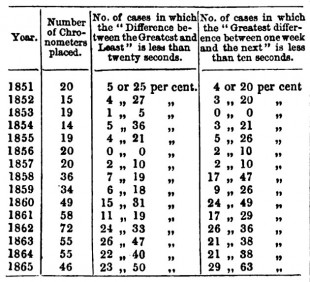

This completes my account of the Greenwich trial as it has for many years been conducted. I may now draw attention to a circumstance which the trials of late years seem pretty clearly to bring out, namely the existence of a gradual improvement in the chronometers sent for trial. In other words, taking any number of chronometers, selected from different makers, and assuming a certain standard of excellence, a greater per centage of them are now found better than such standard than was formerly the case. To illustrate this I go back as far as the year 1851, and taking the yearly printed reports from that year to 1865 (inclusive), I apply to them two tests. I extract, for each year, from the third table of each report, the number of cases in which the Difference between the Greatest and Least is less than twenty seconds, and also the number of cases in which the Greatest difference between one week and the next is less than ten seconds. The following table contains the results:—

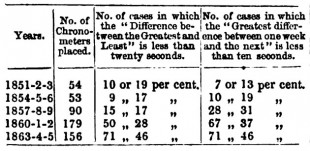

In spite of some irregularities in particular years, improvement is evident. This is better shown in the following table, in which the years are taken together in groups of three:—

These results show that chronometers are now certainly better prepared than was formerly the case; at any rate they are better prepared for the Greenwich trials.

So much in favor of the chronometers. I have now to speak of defects. One defect existing in many chronometers is acceleration of rate. I will instance one or two cases, without referring to any names. In one year a chronometer was deposited, whose rate during the first week of trial was 24s.1 gaining, in the 10th week 54s.5 gaining, in the 20th week 84s.8 gaining, and in the last week (the 29th) 108s.4 gaining. In another case the rates at the same periods of trial were 12s.5, 27s.8, 41s.9, and 60s.2 gaining. In both cases the compensation had been well attended to. In another case a chronometer began with 4s.2 losing, and finished with 47s.1 gaining; another began with 26s.7 losing, and finished with 32s.0 gaining; and others might be instanced. Now these are cases in which the acceleration was proceeding so rapidly, that it would, I should imagine, have been easy for the makers to have ascertained that it existed to so large an extent, before sending the chronometers for trial. Acceleration of rate is sometimes long in disappearing; some of the best chronometers show to some extent, traces of its existence; in such cases it can scarcely be called a defect, but in the instances quoted above, the amount is extravagant.

But now I come to a real defect, the under or over correction of the compensation. The chronometers sent for annual trial, are usually pretty well adjusted for compensation, but still chronometers are constantly received, some extravagantly out in compensation, others, in which the adjustment though not so bad, is still imperfect. I do not know what is the ordinary practice of makers in trying the compensation; I have heard of some who are content with a very short trial. If such is the general practice, it is not surprising that the adjustment is sometimes imperfect, as there seems good reason to believe that a short trial in heat is not sufficient. If a short trial will generally suffice, cases undoubtedly occur in which it will not. And in consequence, it is now established as a rule at the Royal Observatory, that all chronometers shall be exposed to heat for not less than three weeks. The chronometers sent for annual trial undergo indeed two such trials. Now no chronometer maker would willingly send in a chronometer known to be greatly defective in compensation; it seems reasonable therefore, in cases of defect, to suppose, either that he has not tried the chronometer long enough, or that his means of testing the compensation are defective. The necessity for greater care in the adjustment of the compensation, was well shown a few years ago. The chronometers of which I have hitherto been speaking, are chronometers, probably many of them specially prepared for the annual trial, but at the time to which I now refer, several additional trials were held, to select chronometers then required for the Royal Navy, and makers’ ordinary stocks were possibly to a greater extent drawn upon. At the termination of one of these trials (on 1860, November 10) the Astronomer Royal in his report to the Admiralty, spoke of the chronometers as follows:—

An examination of the rates of the chronometers leads me to the following conclusions:—

(A.) The material workmanship of all the chronometers is very good, and amongst nearly all the chronometers there is very little difference indeed in this respect. In uniform circumstances of temperature every one of the chronometers would go almost as well as an astronomical clock.

(B.) The great cause of failure is the want of compensation, or the too great compensation, for the effects of temperature.

(C.) Another very serious cause of error is brought out clearly in this trial; namely, a fault in the oil, which is injured by heat. This is very different with the chronometers of different makers. For instance: the oil used by one chronometer maker (named in the Report) is not at all injured by heat; while some of that used by another chronometer maker (also named) is so bad that, after going through the same heating as those of the first-mentioned maker, the rates of the chronometers are changed (on returning to ordinary temperature) by 80 seconds per week.

(D.) I believe that nearly all the irregularities from week to week, which generally would be interpreted as proving bad workmanship, are in reality due to the two causes (B.) and (C.) .

G.B. Airy,

Astronomer Royal.

When it is considered how very important is the compensation adjustment, it can never be out of place to enforce attention in this particular. Chronometers in which it has not been well attended to cannot come out well in the Greenwich lists, neither will Navy chronometers (of which I propose to speak afterwards) after repair, pass the Observatory test, unless the compensation has been adjusted within close limits. There seems to be a want, in London, of some establishment to which chronometers might be sent for the purpose of being tested, on the same terms as at Liverpool, at which place an Observatory has long been established (under the direction of Mr. Hartnup) principally for this especial work. Any person can send a chronometer to the Liverpool Observatory to be tested, on payment of a certain fee; and one feature of the test is a rigorous trial of the compensation. Some such establishment (of which however I know nothing beyond the mere fact of its existence) was once started in London, but did not from some cause succeed; possibly its existence did not become sufficiently known.

Another case of defect in chronometers is bad oil; of the uncertainty of which makers are generally but too well aware. This matter has however been already referred to in the remarks of the Astronomer Royal, to which I have nothing further to add.

In dismissing now the annual trial from our consideration, I may take the opportunity to correct an erroneous impression which exists, more however with the general public than with chronometer makers. I have seen it sometimes stated that chronometers can be tried at Greenwich on payment of a certain fee. This is not the case. No chronometer, not being a Navy chronometer, can be tried at Greenwich, without special permission so to do having been obtained, and for such trial no fee is required.

I have mentioned the “chronometrical thermometer,” the instrument used for measure of the temperature. Its construction is as follows:—You are aware that a chronometer having a plain (uncompensated) balance, will lose about six seconds daily for each increase of 1° of temperature, in consequence of the change of elasticity of the balance spring. This change appears to be uniform between the temperatures of 30° and 100°. The action of the ordinary balance corrects this. But in the chronometrical thermometer, the balance is constructed with the metals in the arms reversed, the steel being placed outside. The variation of rate for 1° of temperature thus obtained, is double of that instanced above. And the rate of this instrument during any given interval of time, represents the accumulated effect of the temperature acting at every instant during such interval, and is therefore a far better measure of the temperature of the interval, than can be obtained from any readings of thermometers. Its rates are printed in the annual report at the foot of Tables I and II. The change of rate for 1° of temperature seems to be rather larger at low temperatures than at middle, and higher temperatures; it might therefore be slightly preferable to use a chronometer with an uncompensated balance instead of a reversed balance, though by so doing, one half of the change only would be produced.

I have alluded to the effect which magnetism was found to produce in one of the Navy chronometers some years ago. The chronometer in question was Brockbanks 425. In the Nautical Magazine for 1840, page 231, an account of all the circumstances is given by the Astronomer Royal, who also describes a method of correcting the magnetic influence. As this narrative is instructive and complete, an abstract of it may with interest be given here. The chronometer was received in the month of September, 1839, from Messrs. Brockbanks & Co., with a statement that it appeared sensible to magnetic action. The chronometer was rated at the Observatory with the XII placed on successive days, respectively to N, E, S, W, and so on. After being rated for some time, it was found that its mean daily rates were:—

With the XII to North 4s.64 losing.

With the XII to East 8s.70 losing.

With the XII to South 9s.61 losing.

With the XII to West 5s.71 losing.

Now the Astronomer Royal remarks that a case of this kind may be treated in two ways; the permanent magnetism of the balance and balance spring may be destroyed, or a new balance and balance spring applied; or the effect of terrestrial magnetism may be neutralized by the introduction of another antagonistic magnetic force. The latter may be done as follows : — Considering the earth as a huge magnet, having its marked end towards the south; a magnet freely suspended, as a compass needle, will assume a position in which its poles are opposed to the poles of the terrestrial magnet. Consequently the compass needle and the terrestrial magnet act in opposite ways on any other body; so that, by proper adjustment of the distance, the action of the compass needle on any other body may be made to correct the magnetic action of the earth on the same body. This leads to the following practical construction: The action of terrestrial magnetism upon a magnetic chronometer may be annihilated by placing the chronometer upon the top of a compass box, whose needle is perfectly free, provided that its elevation above the compass be property adjusted.

The following experiment illustrates this. Place a small compass upon a large one, the marked end of the small compass will point S. Elevate it to a great distance above the large one, its marked end will then point N. But there is an intermediate position in which the needle of the small compass will rest in any direction. And this is the elevation at which the magnetic part of the chronometer ought to be placed, in order that the effect of terrestrial magnetism may be entirely corrected. Proceeding according to the method described, the Astronomer Royal constructed a wooden box or dish, with ledges for the support of the chronometer, and with a central hollow or well for a compass, and adjusted the position of the compass so that the balance of the chronometer might be at the same elevation as the needle of a small compass had been when its directive power was destroyed. On now rating the chronometer, its mean daily rates were found to be:—

With the XII to North 6s.90 losing.

With the XII to East 8s.10 losing.

With the XII to South 8s.17 losing.

With the XII to West 6s.75 losing.

The discordance was thus reduced, but had not entirely disappeared. The distance between the compass and the chronometer was reduced half an inch. The rates then were:—

With the XII to North 9s.24 losing.

With the XII to East 9s.41 losing.

With the XII to South 9s.75 losing.

With the XII to West 10s.03 losing.

The correction appears now to be a little overdone, but so little, that the chronometer may be considered practically as free from magnetism. The most probable explanation of the necessity which existed for reducing the first distance half an inch, seems to be, that the part most susceptible to magnetic action was not the balance, but the balance spring. In passing through different magnetic latitudes, the distance would require to be occasionally changed; the amount of change can however at any time be easily ascertained, by means of a small compass, in the way already explained. In any one magnetic latitude, the arrangement which corrects a small discordance of rate, will manifestly also correct a large discordance of rate.

The above then is the method which the Astronomer Royal devised for correction of the discordance of rate produced by magnetism. Cases of this kind are however rare; when such do occur the most satisfactory course to pursue is certainly to replace the affected parts by new. But the method might be used at sea, or when opportunity for renovating the defective chronometer does not exist.

To what I have already said, it may be interesting to add some account of the routine of management of the chronometers of the Royal Navy. To illustrate the system I will trace the supposed history of one such chronometer. It may have been received from one of H.M. Ships when put out of commission, or may be returned as defective. On its arrival at the Royal Observatory, it is examined to see whether any rust exists, whether any parts are broken, and generally, the state of the chronometer as far as can be ascertained by such inspection. If all appears to be in good order, and if the chronometer has been recently in the hands of the maker, it is added to the general store, and if on rating, it is found still to perform satisfactorily, it is issued, as occasion arises, to any other ship requiring chronometers. But we will suppose the chronometer to require the maker’s attention. Notice is then given to the maker, asking him to send some person to the Observatory on the Monday following, between the hours of ten and one, to open and examine the chronometer and remove it for the purpose of furnishing estimate of the expence of repair. It is a rule that chronometers can only be delivered to, or received from makers, on Mondays, between the hours mentioned, unless special instructions are given. When the agent calls, he opens and inspects the chronometer in the presence of one of the Observatory officers, and reports all defects he can by such examination discover. It is then conveyed to the maker, who after more complete examination, transmits to the Astronomer Royal an estimate of the expence of repair, giving also details of the work proposed to be done, and mentioning at the same time the probable period which the repairs will occupy. The estimate having been considered by the Astronomer Royal, is sanctioned, if thought to be fair. But there is considerable difference in the charges of different makers for what appears to be the same work. When the period at which the chronometer maker expects to be able to return the chronometer effective has passed away without its being received, notice is (after allowing some grace) sent, to ask him when it is likely to be ready. It will be understood that there is no desire unduly to hurry necessary work (which may consume a longer time than was expected) but that we wish to prevent unnecessary delay. When the chronometer is returned as effective, it is rated for some weeks in the room; it then undergoes a three weeks’ trial in heat, the highest temperature to which it is exposed being about 85°, or from 85° to 90". If the compensation is found satisfactory, and if the chronometer, after removal from heat, continues to perform satisfactorily, it is considered fit for service, and is rated until orders are received from the Admiralty directing its issue to some ship of H. M. Navy. But should the trial be unsatisfactory, the chronometer is returned to the maker, with intimation of the particular defect of rate requiring correction; a copy of the rates being also sent for the maker's information. The expence of this attention is understood to he covered by the estimate, unless, as will occasionally happen, some other considerable repair is eventually found to be necessary, to place the chronometer in a proper state; some heavy repair, for instance, such as probably it would have been scarcely prudent to authorize until by trial it plainly appeared that such repair was required. But in all such cases, a new estimate must be sent in, and sanction for it obtained, before such additional work is proceeded with. The chronometer being again returned to the Observatory, and having finally satisfied the Observatory test, is passed for service, and continues to be rated until so required. It is expected that the compensation will be adjusted by the maker as accurately as is possible, and in many cases it is found to be very satisfactorily done. In the case of navy chronometers having the ordinary balance only, it is found better that the defect of the balance to lose in extremes should be thrown rather on the cold than on the heat, as chronometers are constantly taken to warmer climates, seldom to colder, and indeed in cold climates they are protected in the ship’s cabin from exposure to excessive cold.

It is remarked in chronometers received from service that in cases in which rust is exhibited, the bright steel parts usually suffer first. But exceptions to this have been noticed. On some occasions, and in several cases of new chronometers, the blued balance spring has been found covered and ruined by rust, whilst no other portions of the chronometer showed signs of rust. I mention this as a fact, leaving it to chronometer makers to furnish an explanation. The defect may perhaps be connected in some way with the manufacture or preparation of the spring.

All correspondence relating to estimates and repairs &c. of chronometers is transacted with the Astronomer Royal, but all bills for payment of work done should be sent to the Hydrographer, at the Admiralty, Whitehall.

It might be interesting to describe our system of book-keeping as applied to chronometers, but time will not permit, I may mention, however, that a very complete system exists; there is for instance a day book, in which all receipts and issues are entered on opposite pages; another day book for repairs; the entries in these books being regularly posted into ledgers. By these ledgers the history of any chronometer can be immediately ascertained, or the amount of repairs done and expence incurred for repairs, &c. But I must not consume more time by entering further into this subject now.

* Capt. Richards, R.N., at present holds the office of Hydrographer to the Admiralty.

© 2014 – 2026 Graham Dolan

Except where indicated, all text and images are the copyright of Graham Dolan